Tag: Housing

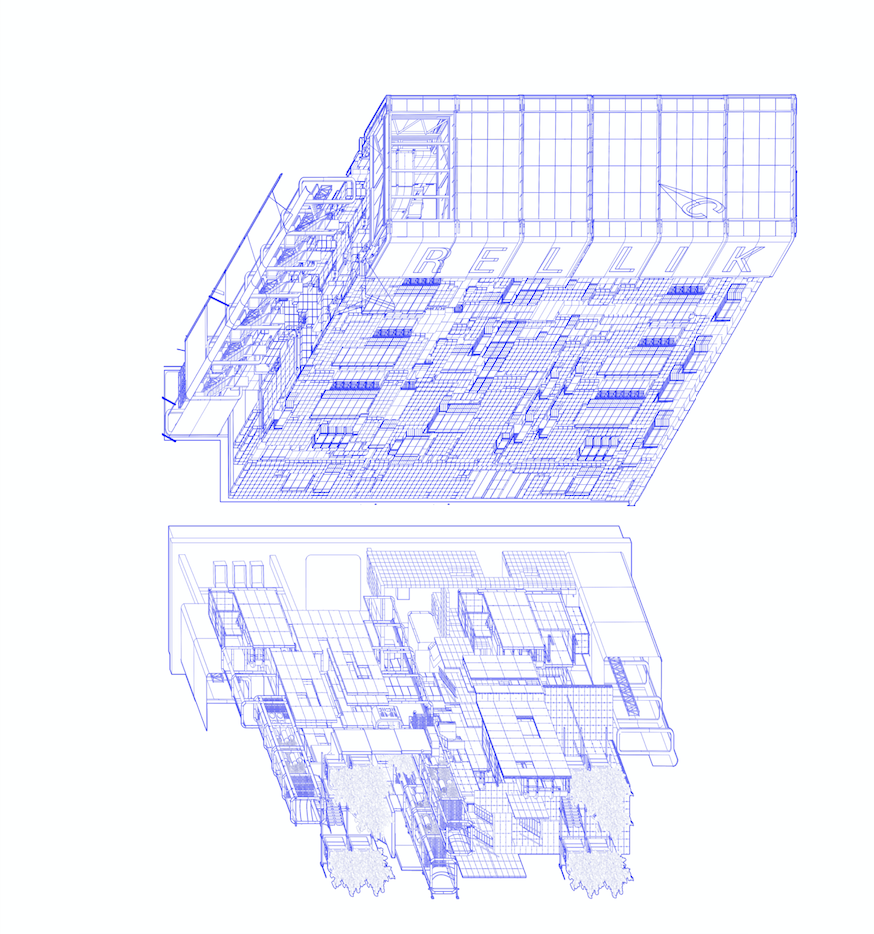

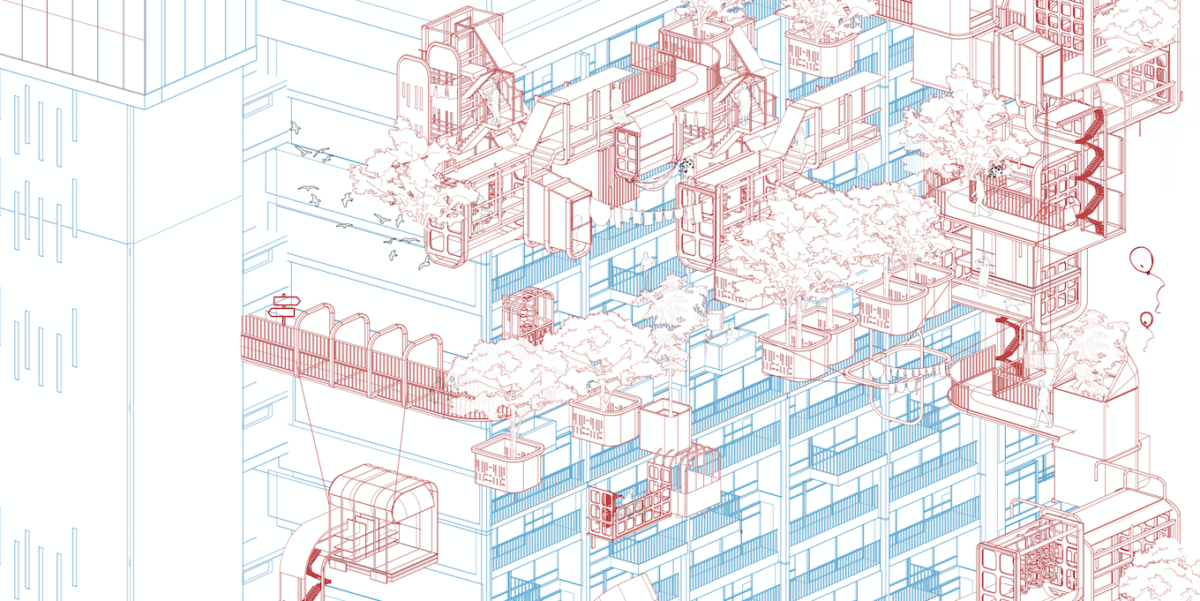

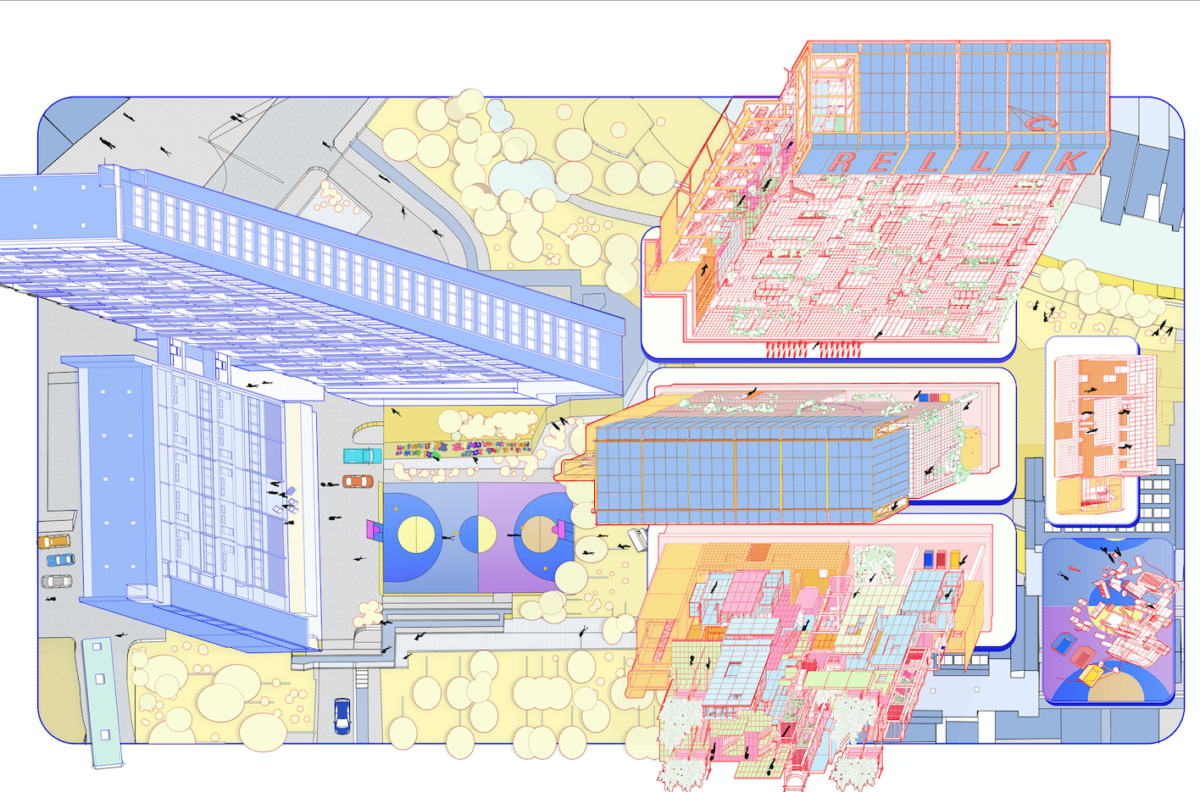

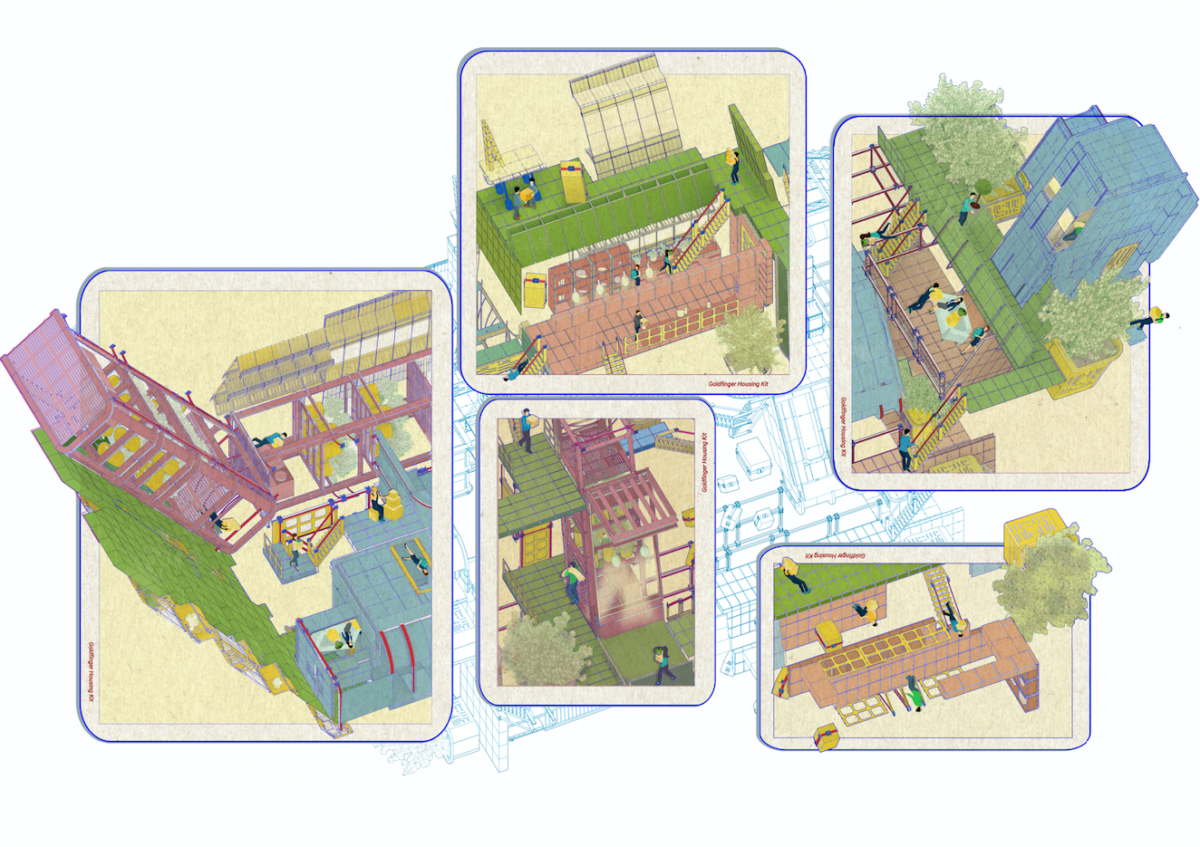

(RE) TRELLICK

Goldfinger Housing Kit

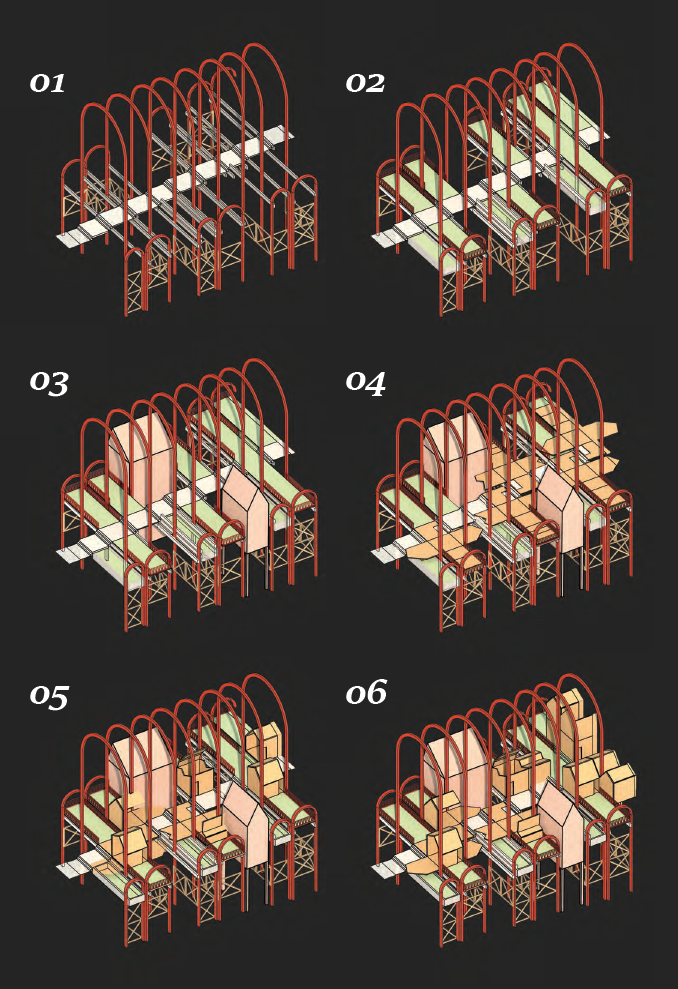

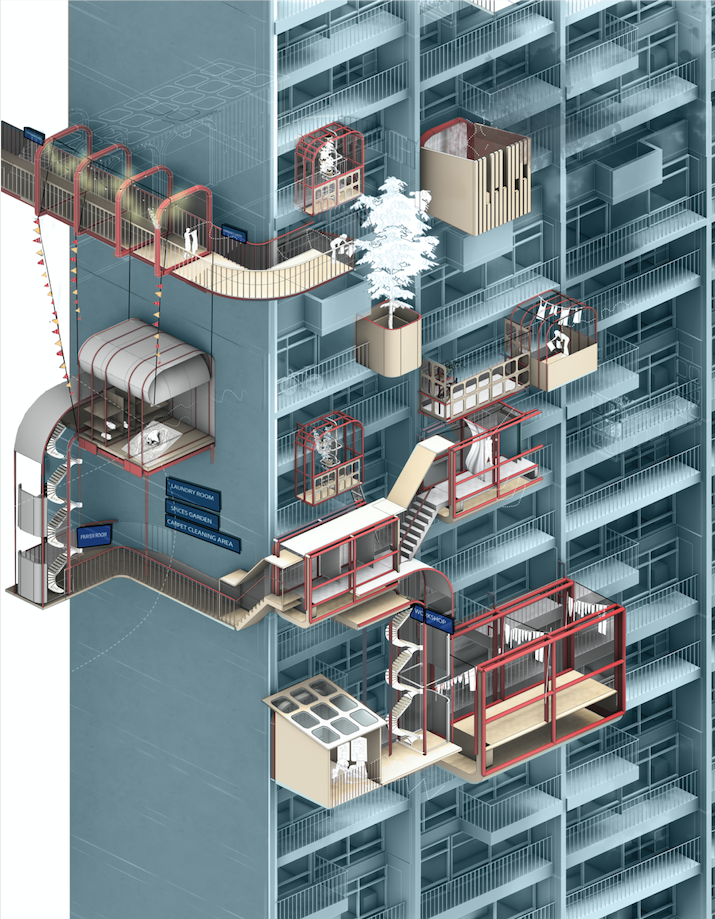

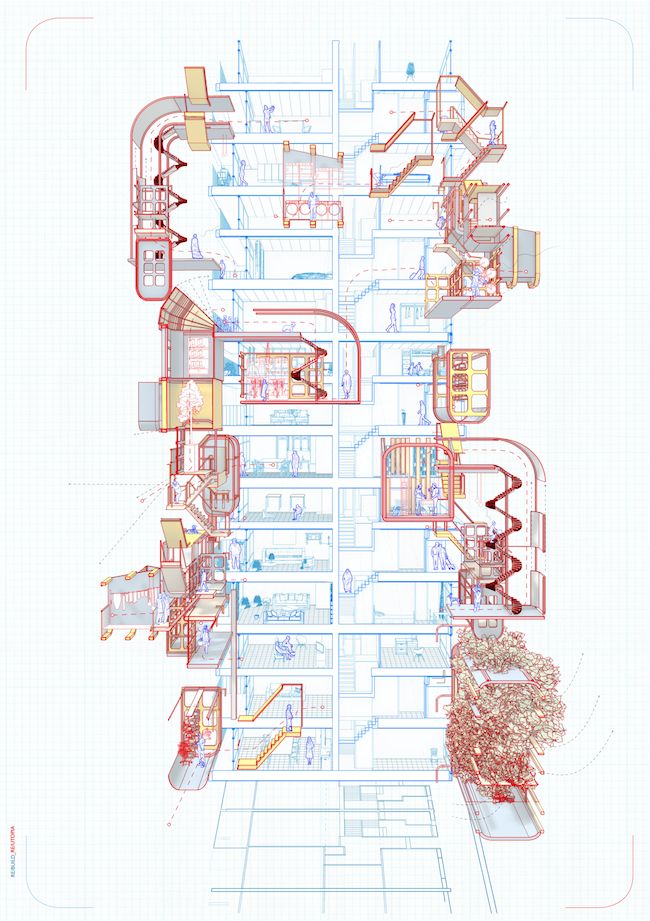

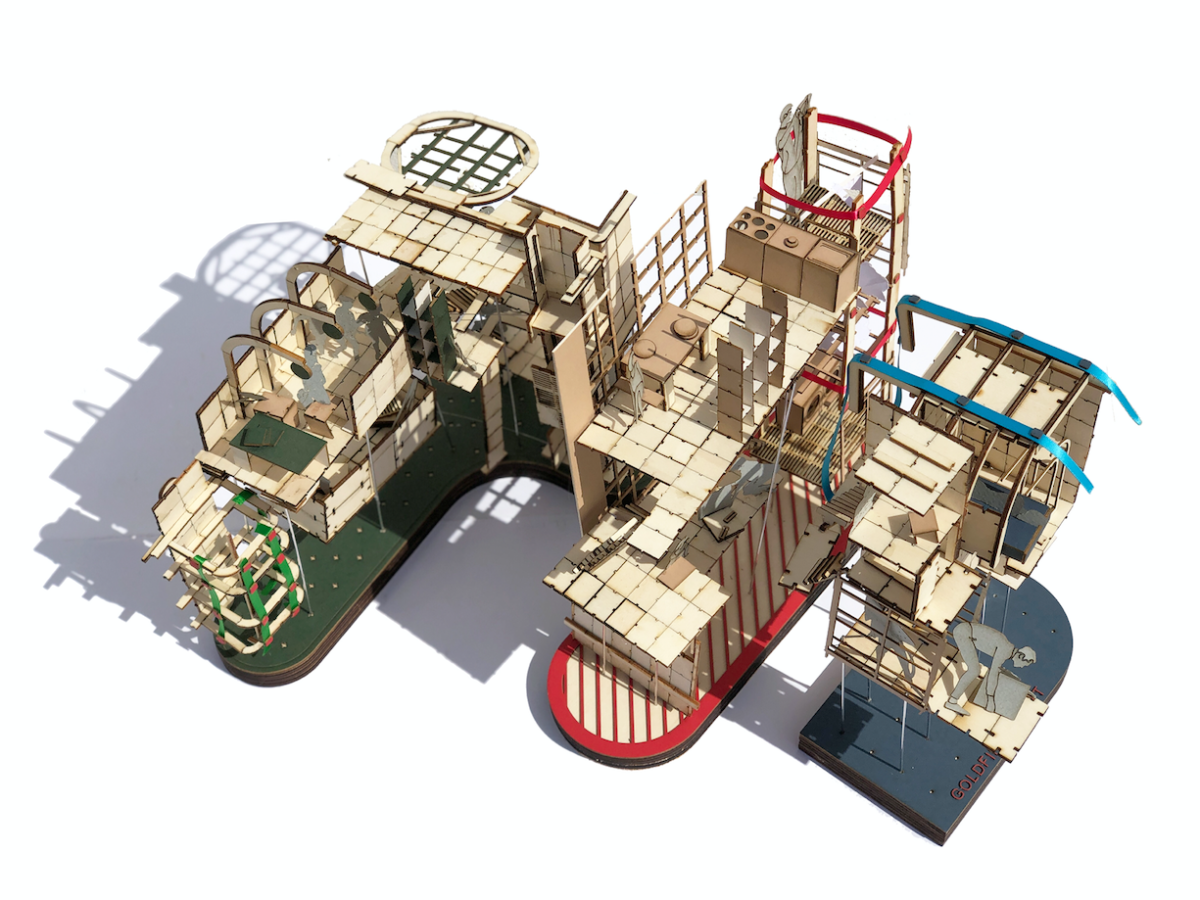

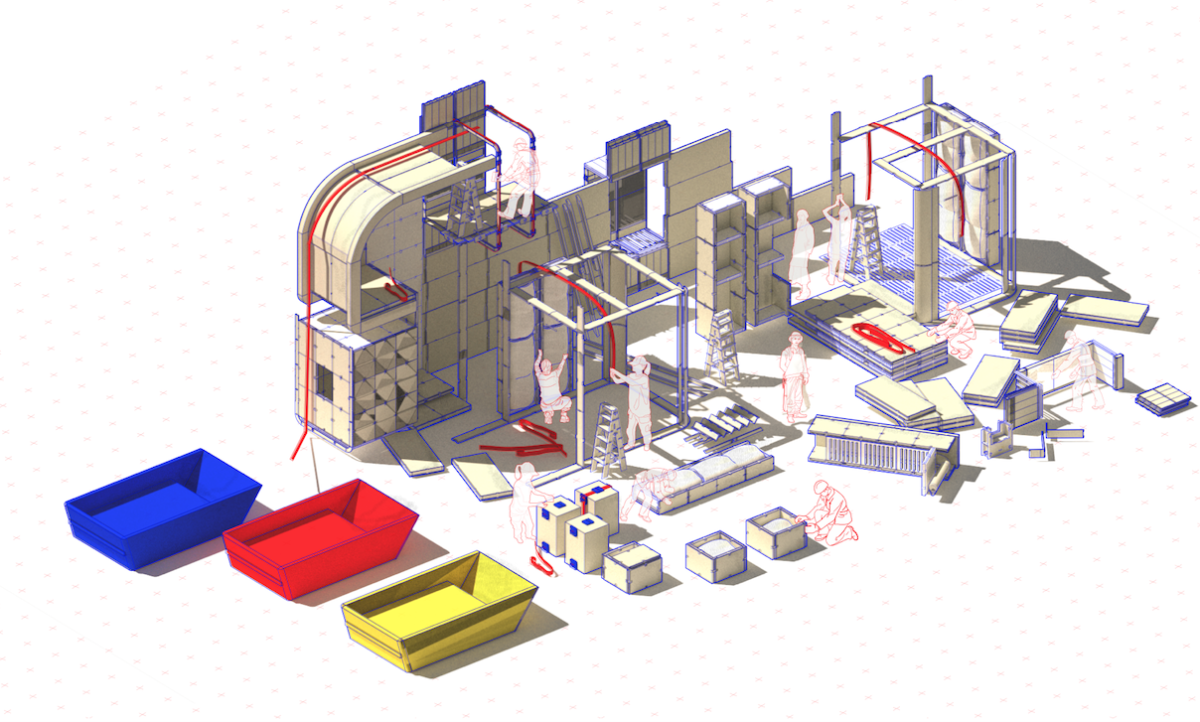

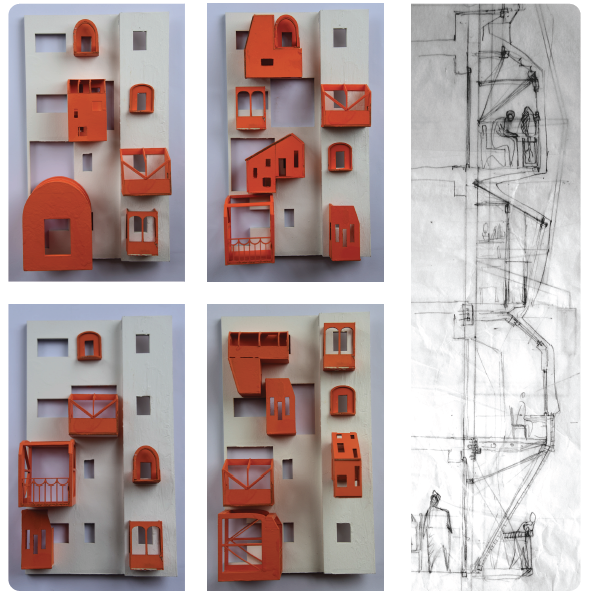

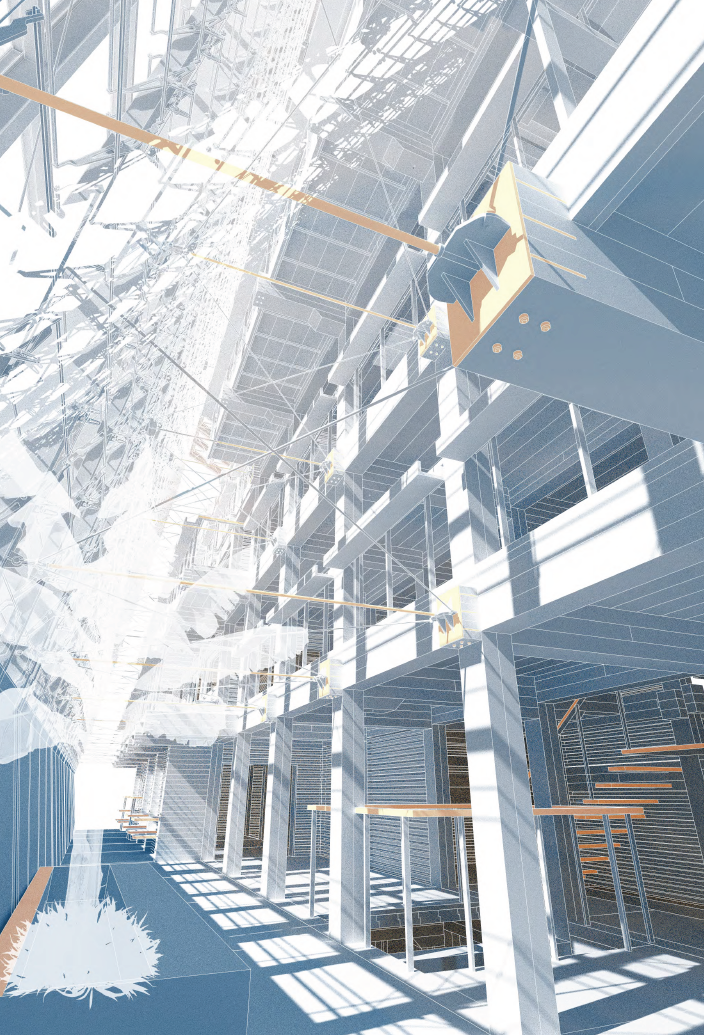

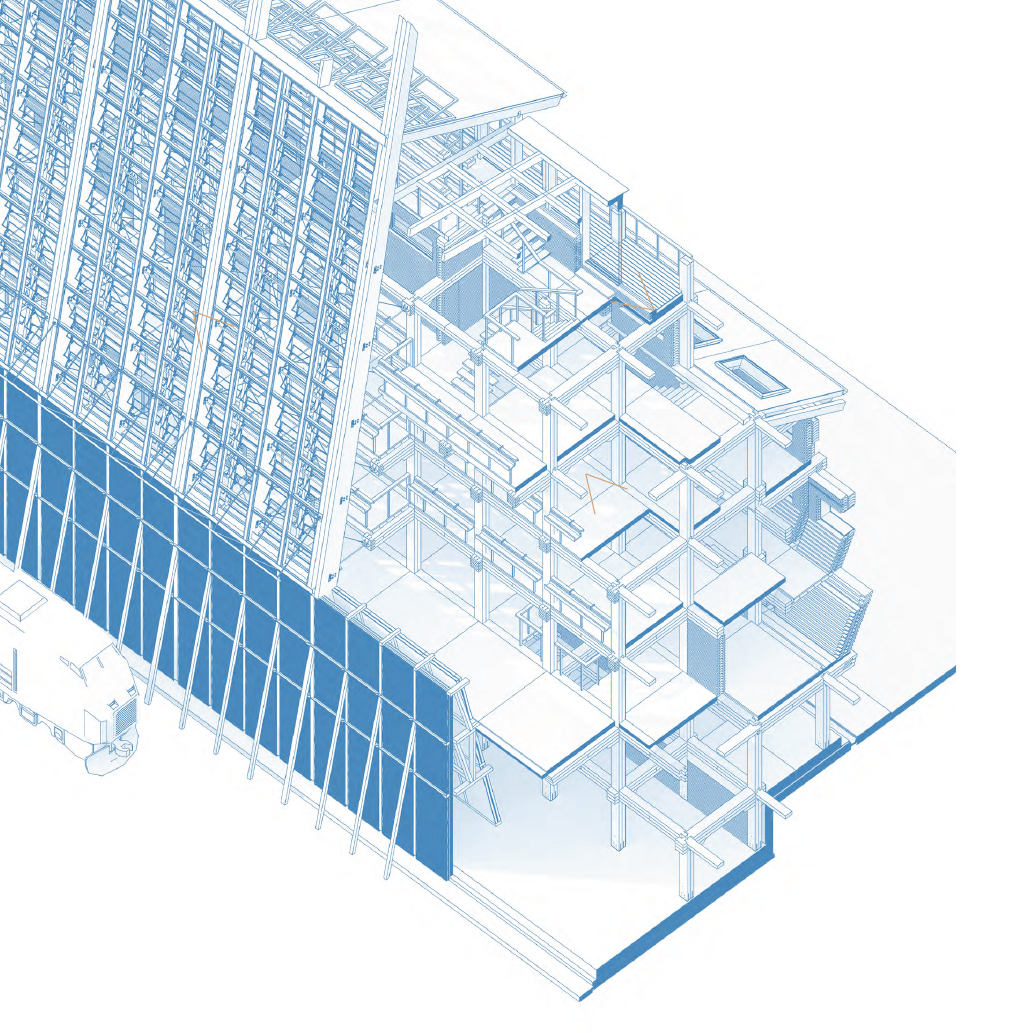

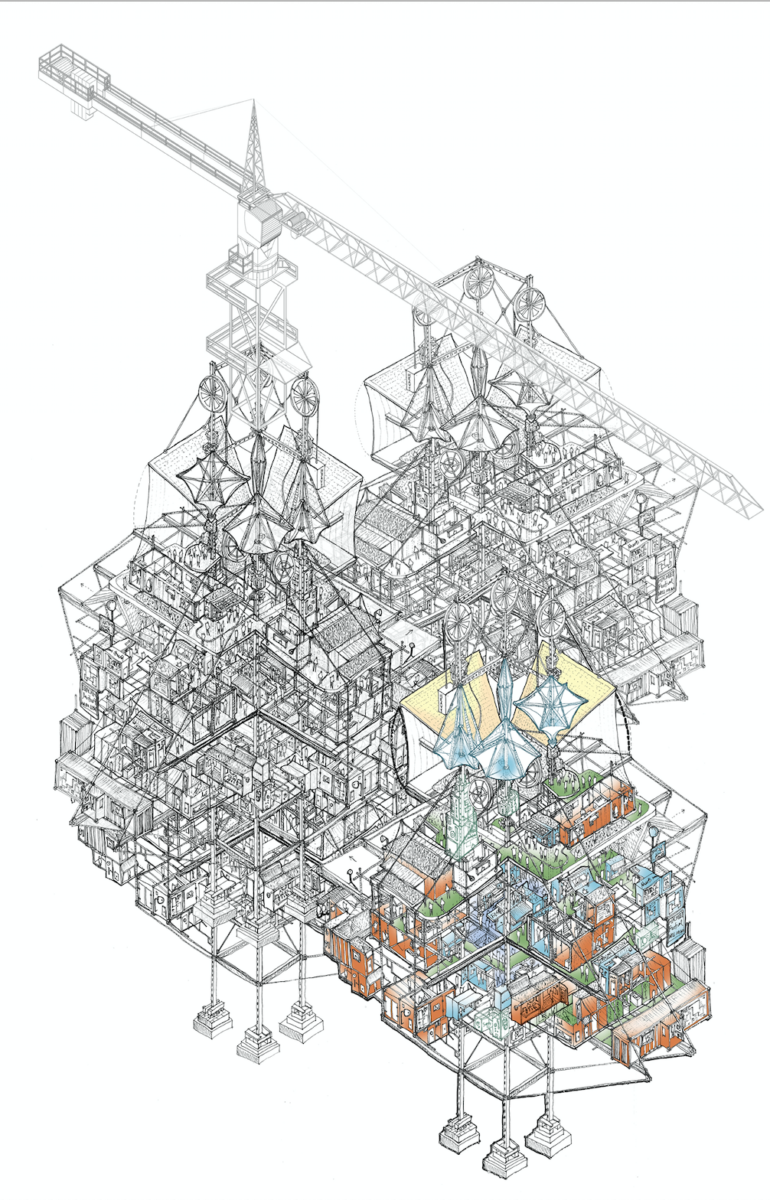

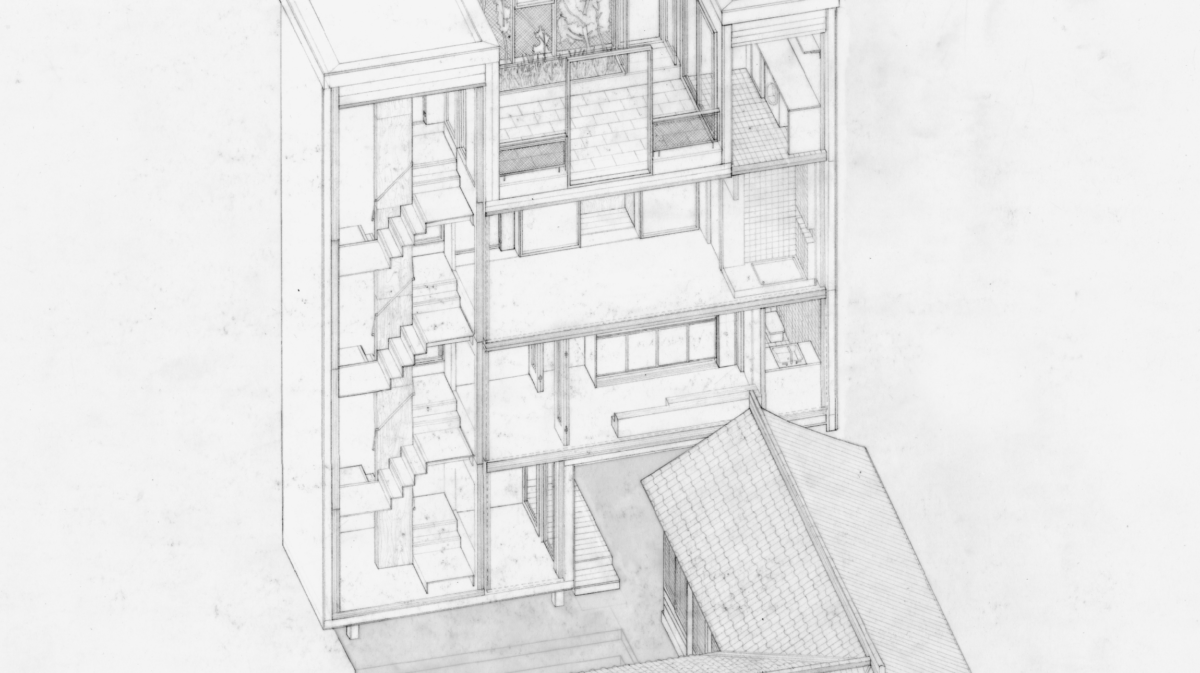

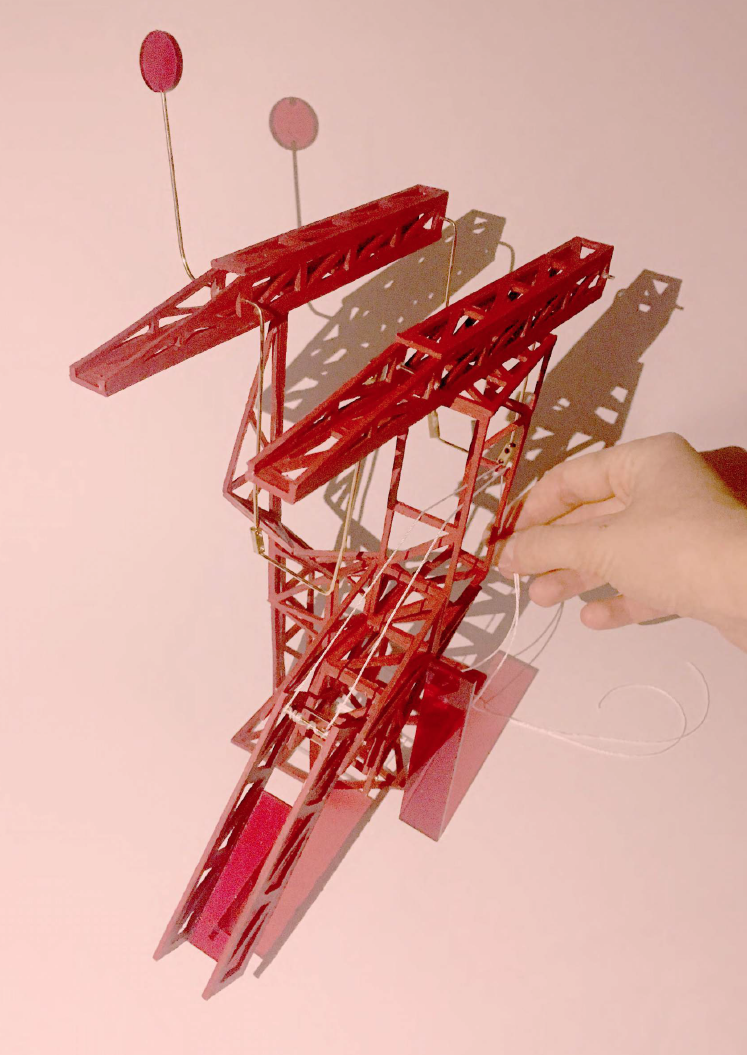

The project is a proposal for a self-build tower, entirely made of timber modular components. These are small interlocking “boxes” which can be easily carried by people due to their portable size. The evolution of the components follows the narrative around the activity of the self-builders, residents of the existing Trellick Tower, project’s site. The builders are able to fabricate this kit of parts in the workshop of the Goldfinger Factory, which is placed at ground level of Trellick Tower. This is one of the biggest social housing schemes in London and it is currently home for a variety of cultures, who are part of the Trellick Tower Residents Association. In tis contest, the group of self-builders engage with the making and the management of this pioneer self-build scheme.

This tower grows over time as the self-builders carry on the construction phase. This proposal involves the local borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the ward of Golborne.

The components are inspired by the analysis of Balfron Tower, another residential tower designed by Ernő Goldfinger, providing key elements for the comparison and improvement of the same elements, which were missing in the design of Trellick Tower. The whole design of the components and the kit of parts is a re-elaboration of this iconic details, which have been reinterpreted and re-designed with a new assembly concept.

The project followed four phases, from an initial addition of components to the existing Trellick Tower to the development of a kit of parts. This has transformed the components from phase1 into a manual of construction for the realization of a new building: Trellick 2.0.

This self-build design approach enables the residents to actively take part in the process of creating new flats typologies, through Utopian lenses. Extended communal gardens, shared kitchens or laundrette spaces shared by multiple levels cut through the building, connecting different flats across different floors. Externally the building would imitate Trellick Tower facade, hiding this intricate space.

The project aims to strengthen the community not only of Trellick, but of the entire surroundings of Golborne. The residents are able to build up skills and become professional manufacturers, therefore they also become pioneers of a new self-build system, replicable anywhere else. The tower will be adapted and changed over time by the residents and will be self-funded by the circular economy structured around the proposed Trellick Tower Residents Housing Association, adding social values to the project.

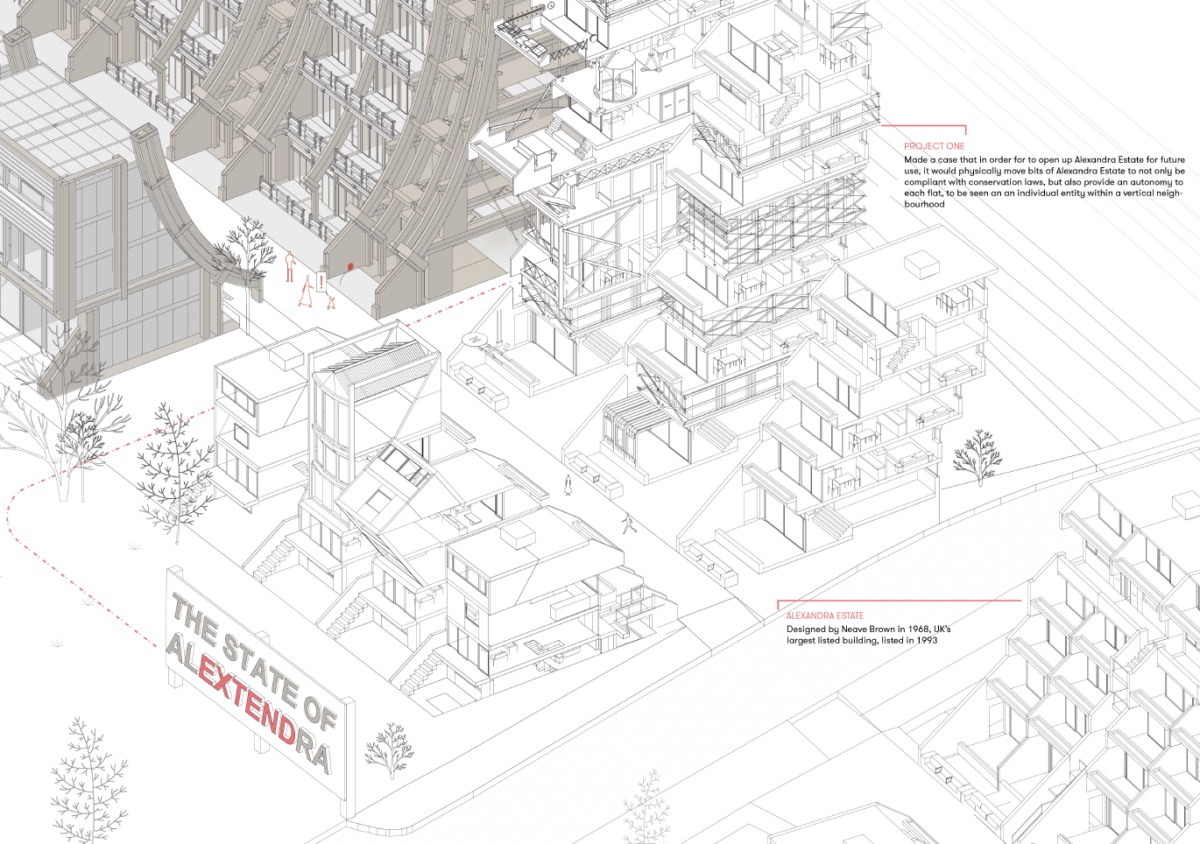

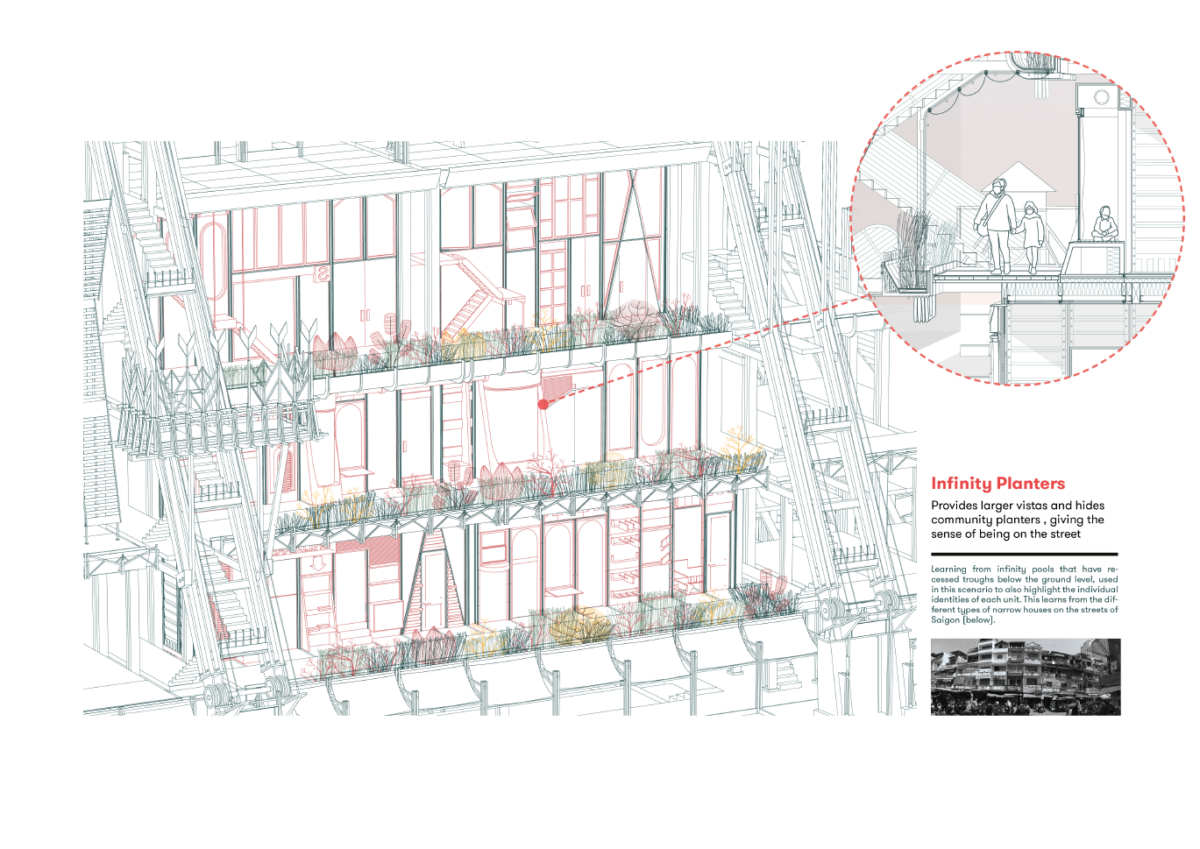

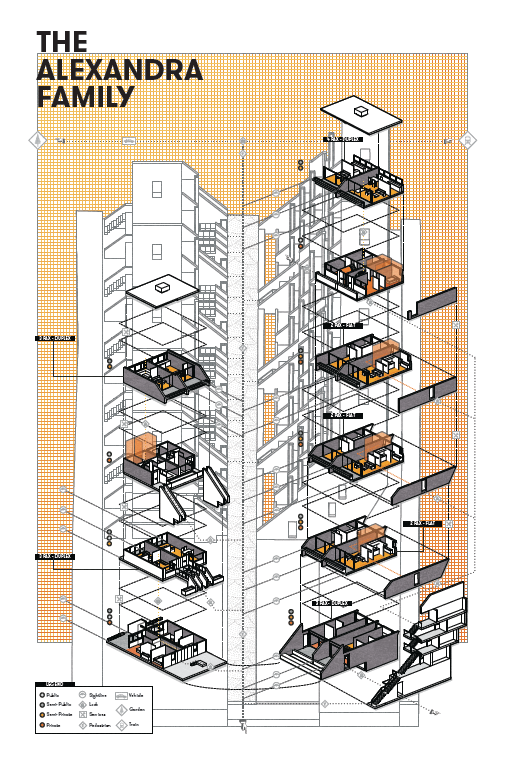

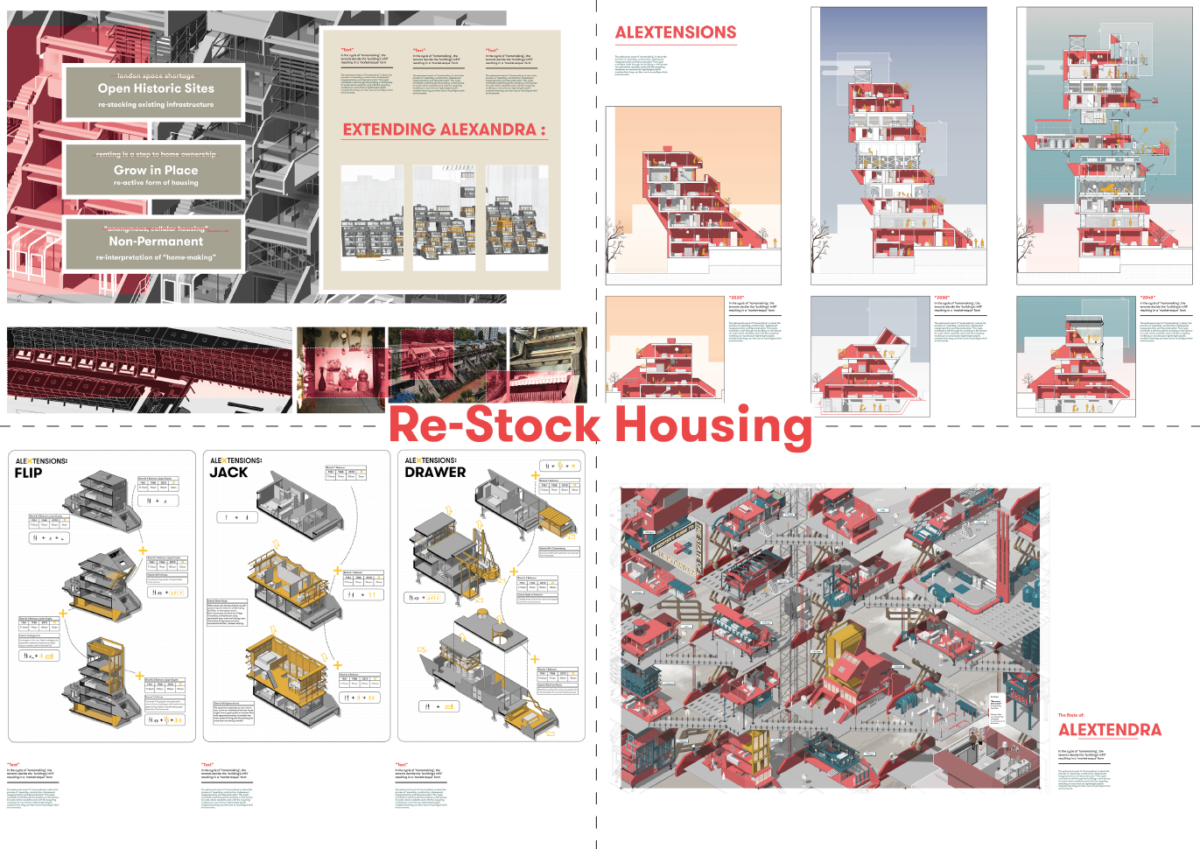

The State of Alextendra

What is the role of the architect in “homemaking”?

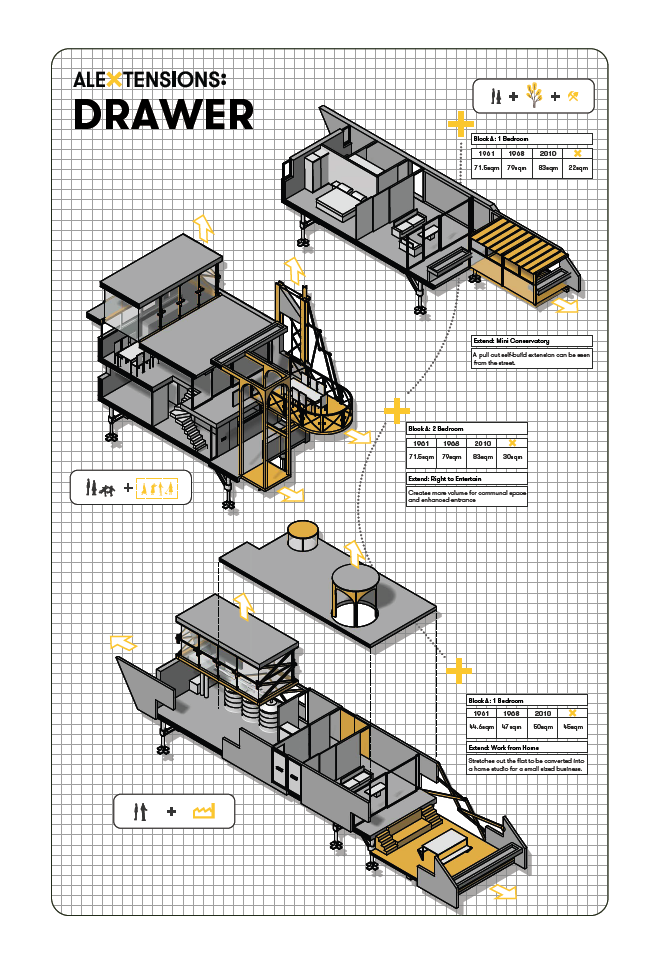

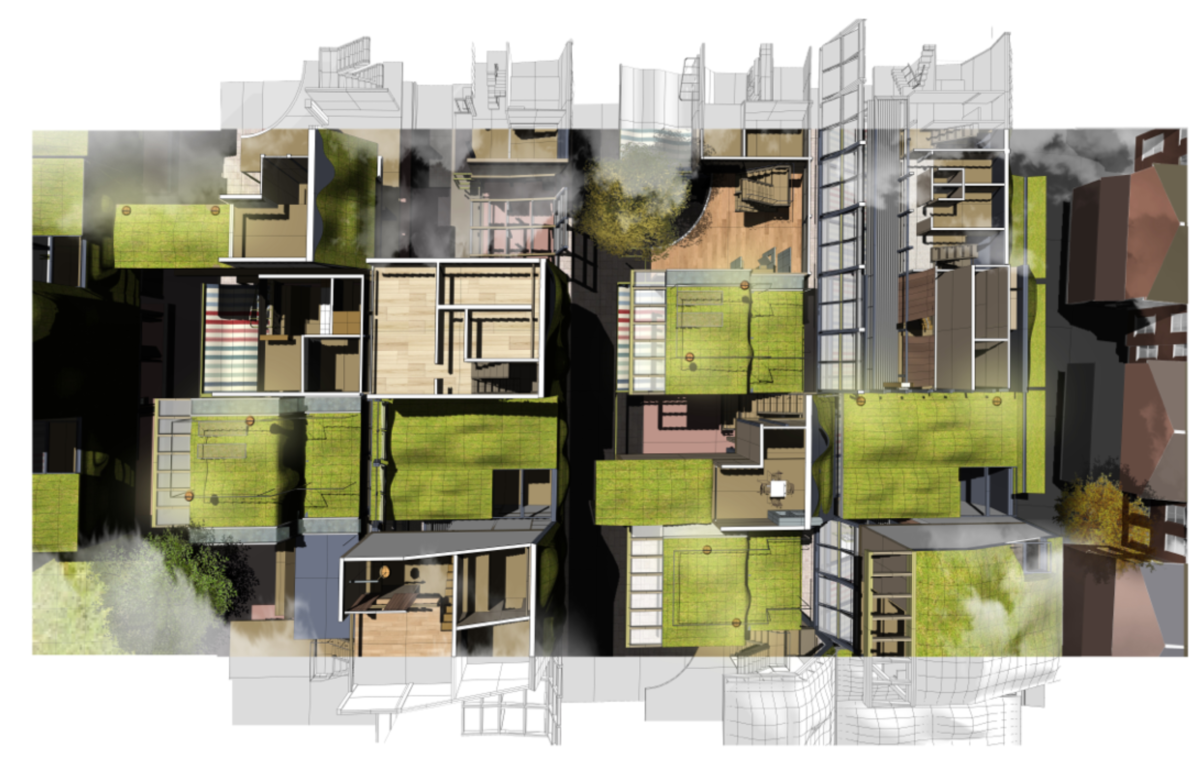

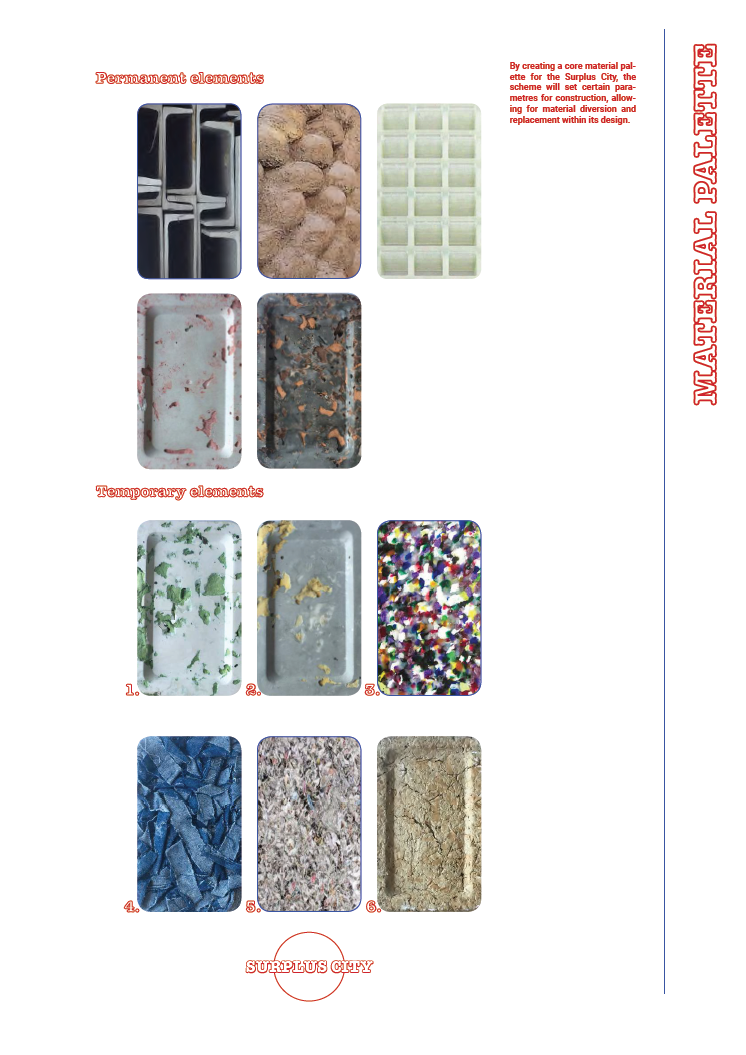

The State of Alextendra discovers ways to extend Neave Brown’s iconic Alexandra Estate into the 21st Century by redefining “homemaking” and proposes a form of affordable housing that re-acts to changing tenant needs and identities; creating a utopic vision of a form of housing that allows tenants to continually readapt their environments using local, recycled materials.

The State of Alextendra firstly challenges the form of housing and discovers ways to allow tenants within Alexandra Estate to grow and modify their flats using temporary structures to re-arrange the listed components of the iconic estate. It provides new opportunities for flat extensions (called “Alextensions”) whilst retaining its historic value.

It then contextualises it on a site adjacent to Alexandra Estate and discovers how tenants can sustainably have a leading role in the process of their own homemaking. This challenges the traditional process of delivering housing schemes by introducing a “market-esque” typology that believes people should live in homes not in housing units.

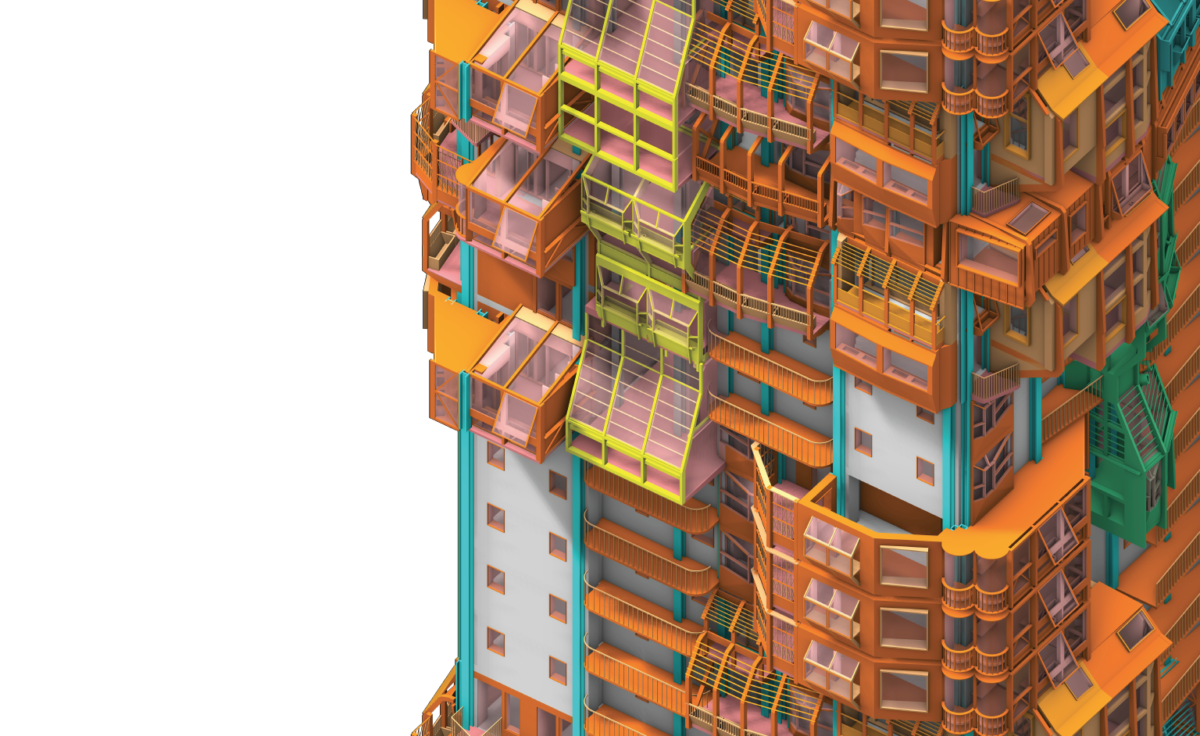

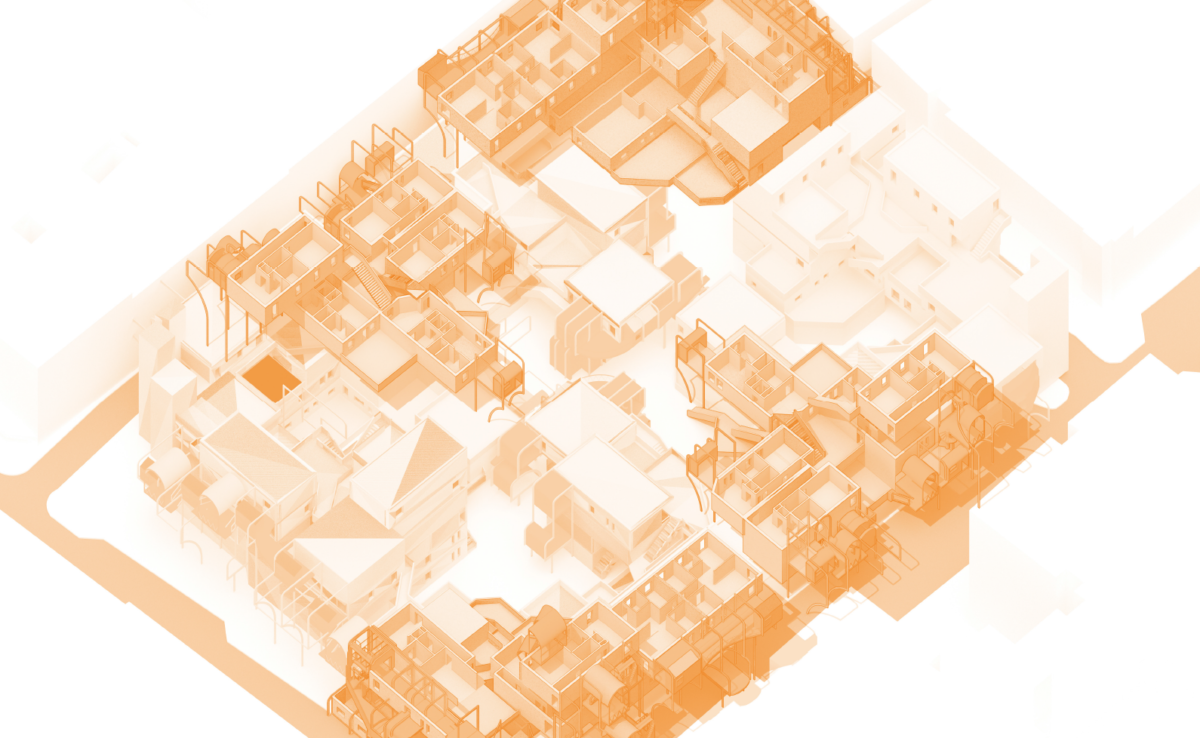

Commoning for Housing

In studying two social housing projects this year I have begun to develop an interest in the potential for commoning spaces with an aim to enhance the resident experience as well as better connect them to the surrounding city. At Odhams Walk I observed an active public life maintained by the village-like atmosphere of the architecture. In speculating about the possibility of allowing residents to appropriate spaces within the housing project for temporary functions, I developed a kit of parts that can be inserted onsite to allow for a secondary function.

At this point I changed site to Ampthill Square Estate as it allowed me to hone the kit of parts more. Whereas Odhams consisted of 5 different unit types, Ampthill Square Estate contains three towers with 240 identical units. This provided a key opportunity to test the efficacy of communal components. This project seeks to understand how residents can use communal living to modify their homes to meet their needs at the scale of their flats as well as the tower as a whole.

NUEVA COSTA DEL ALEXANDRA 2050

An Active Ageing Utopia Amidst Continued Carbon Offsets

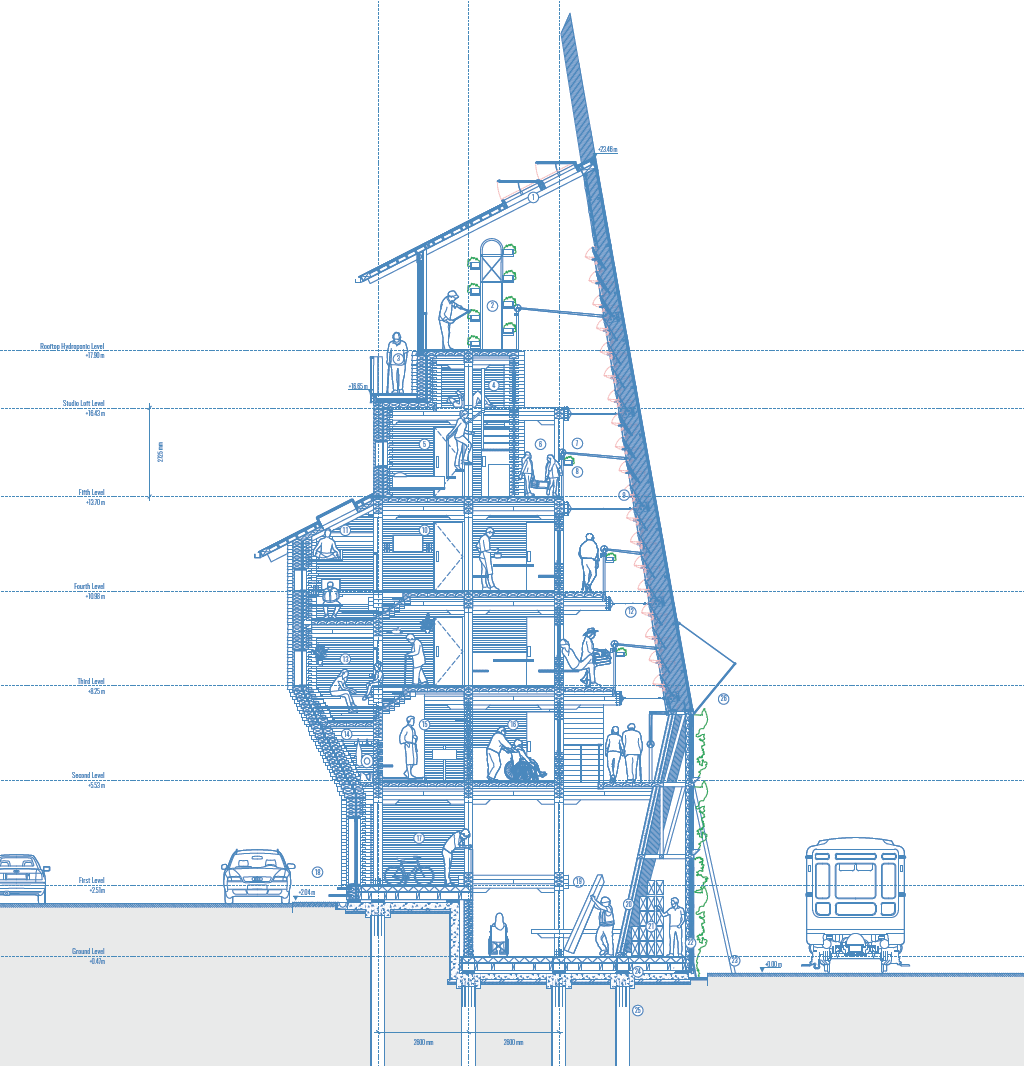

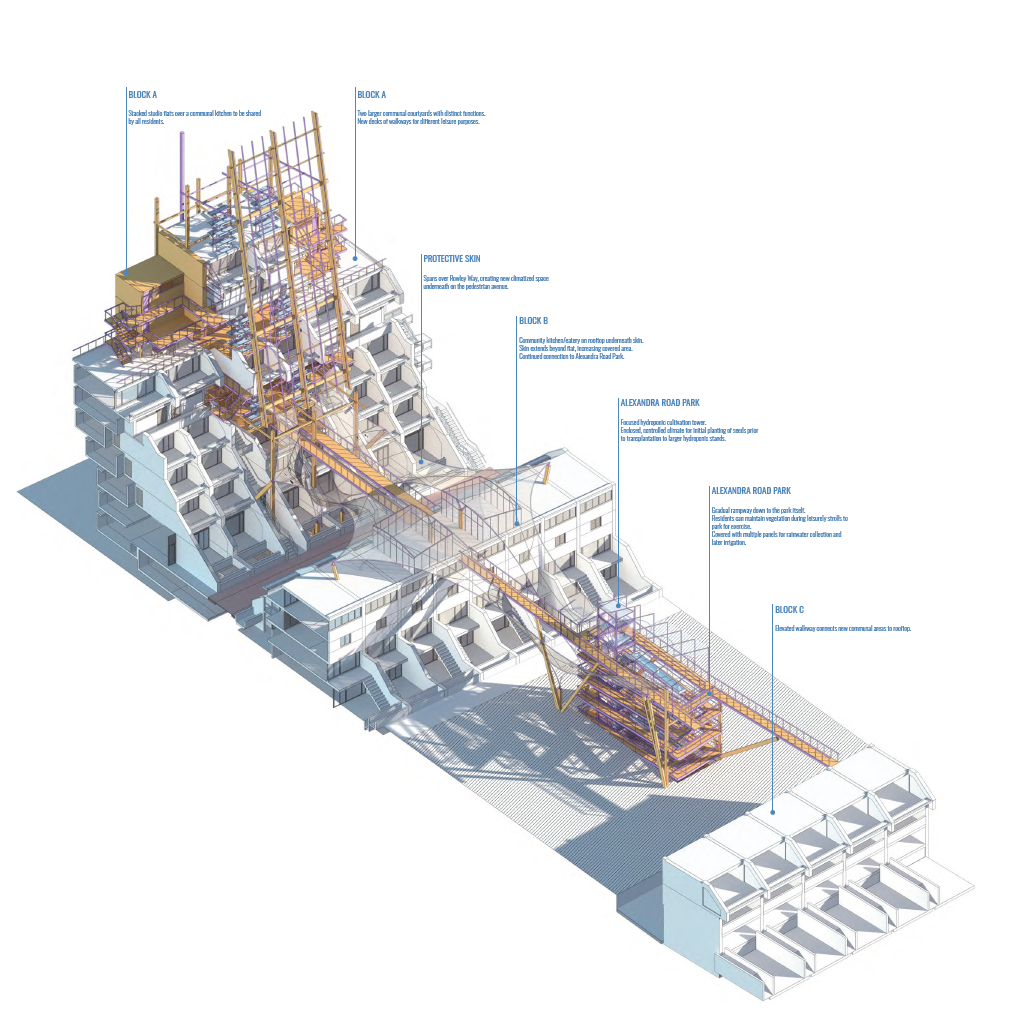

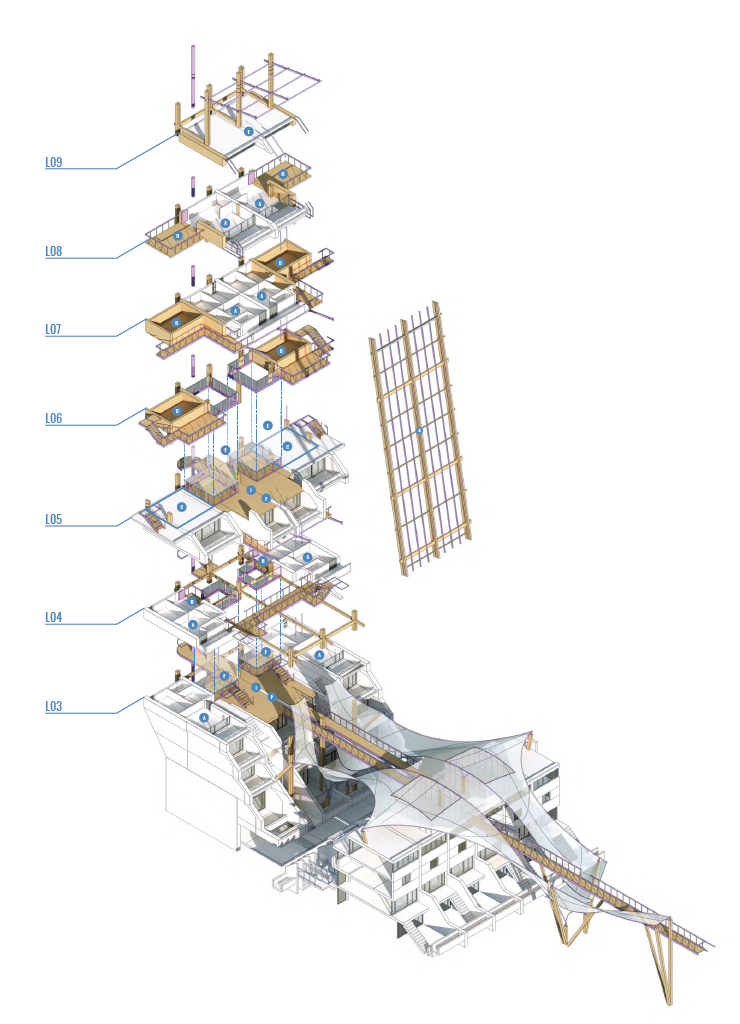

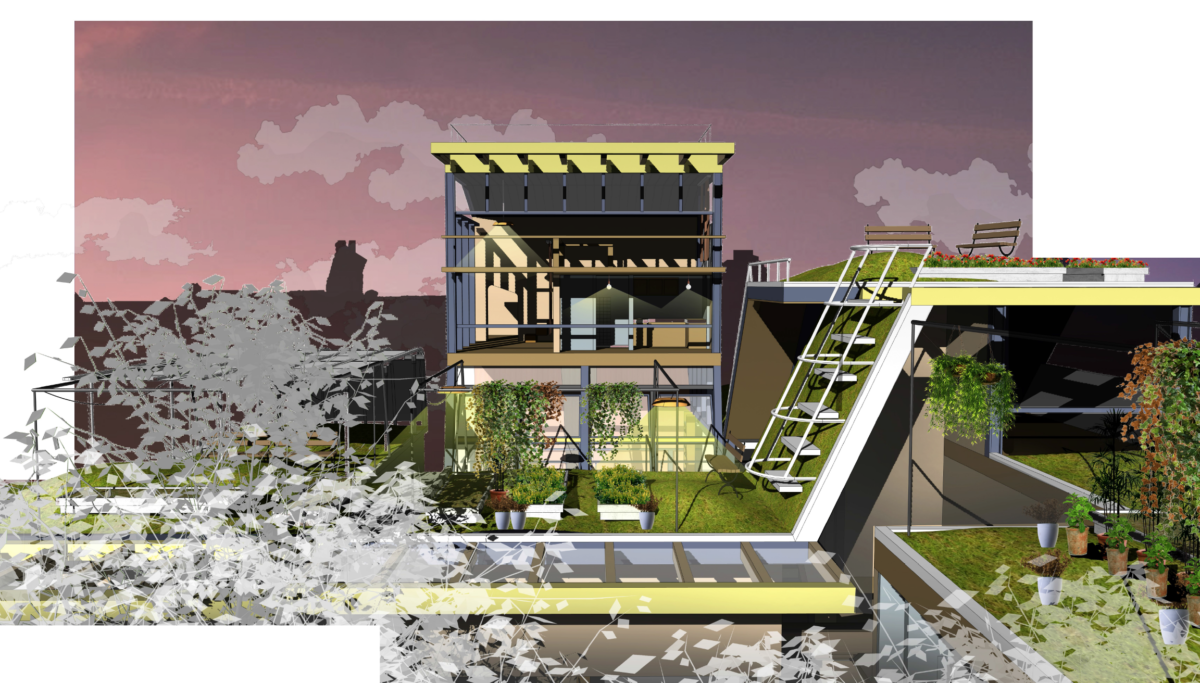

Neave Brown’s Alexandra Estate (Kilburn, Camden; 1978) vision, initially dubbed “Costa del Alexandra” after the sunny retirement utopia of Costa del Sol, has gradually weathered away. As it aged, so did its residents and the UK (1/3 are 65+). With retirees projected to grow 20-25% by 2050, these issues, coupled with likely-reduced pensions/care, social isolation and material deprivation, present unappealing retirement on the estate and its ward. Future climate change further threatens retiree livelihoods.

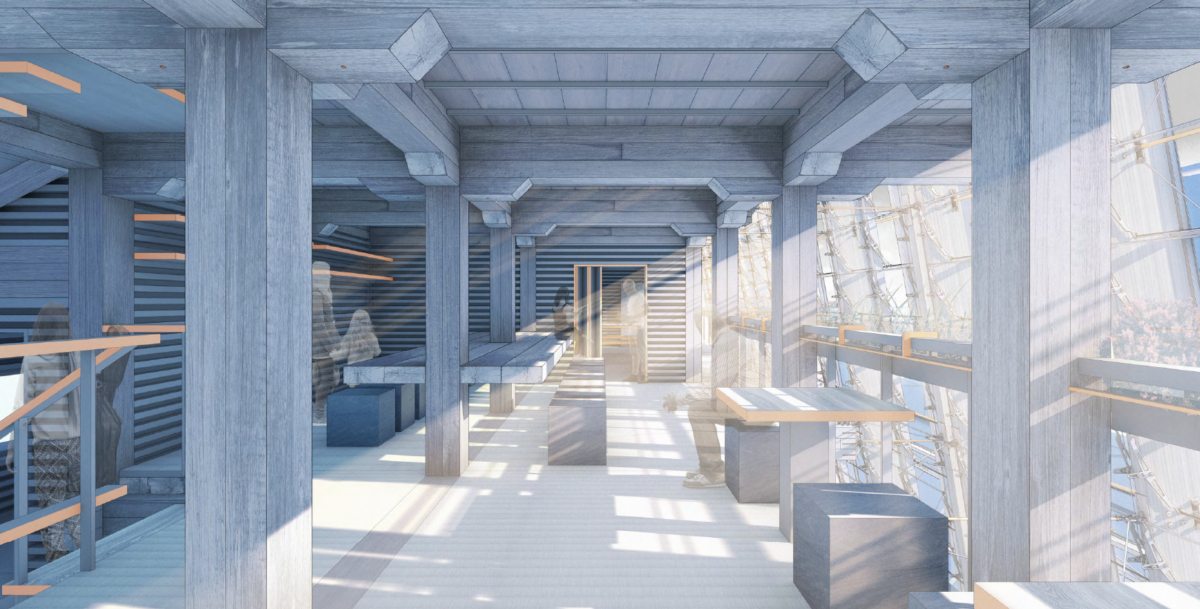

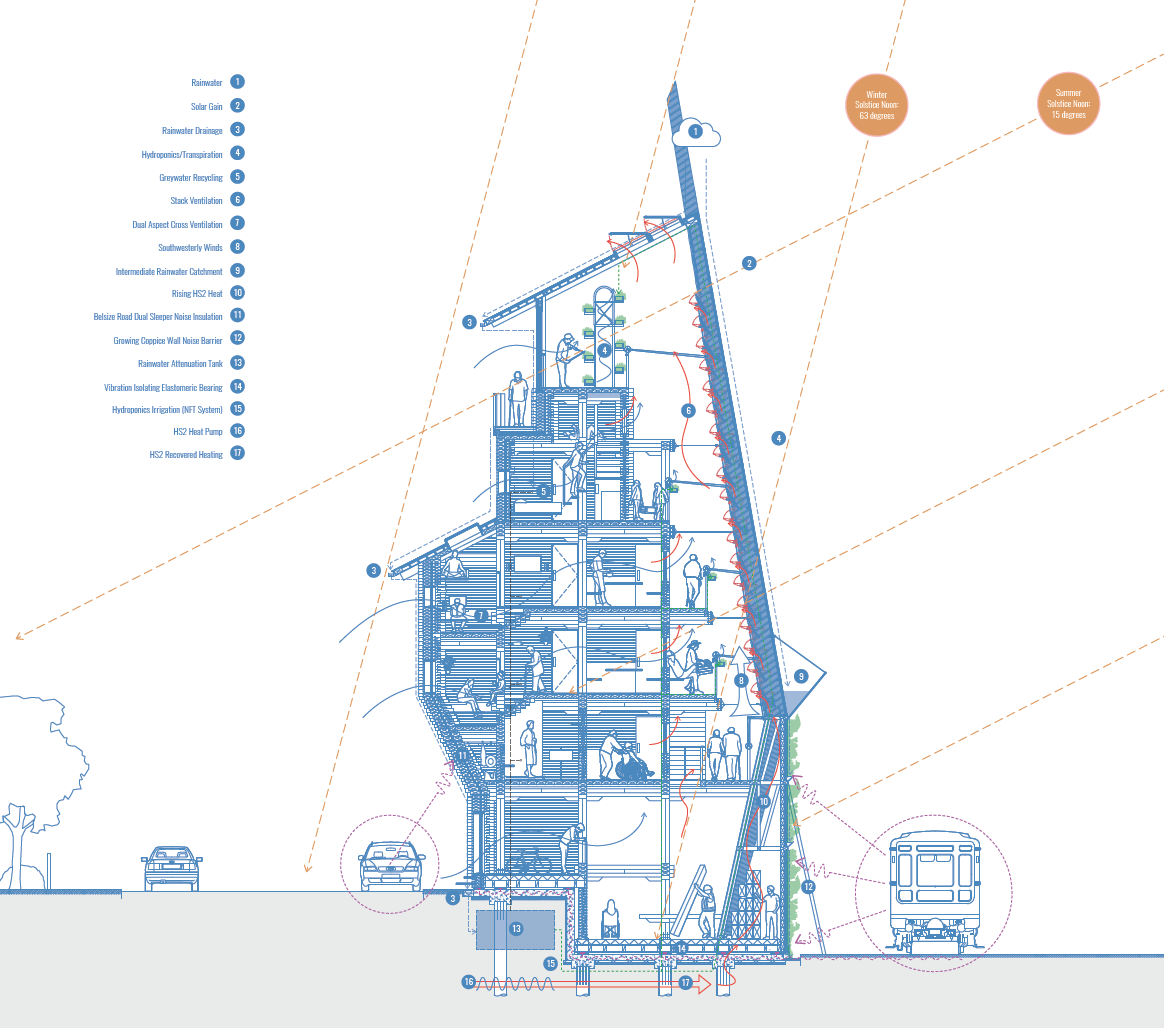

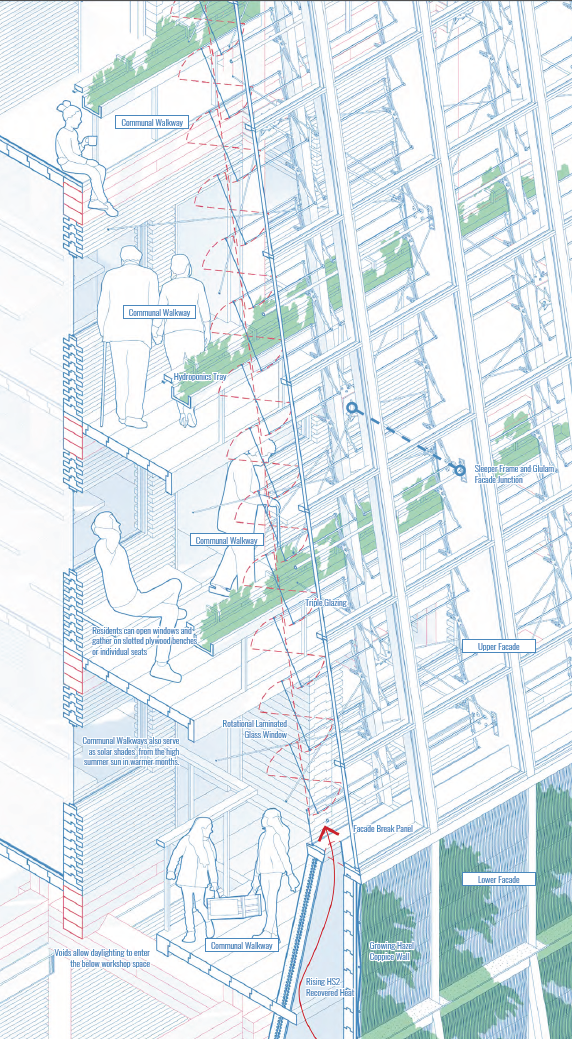

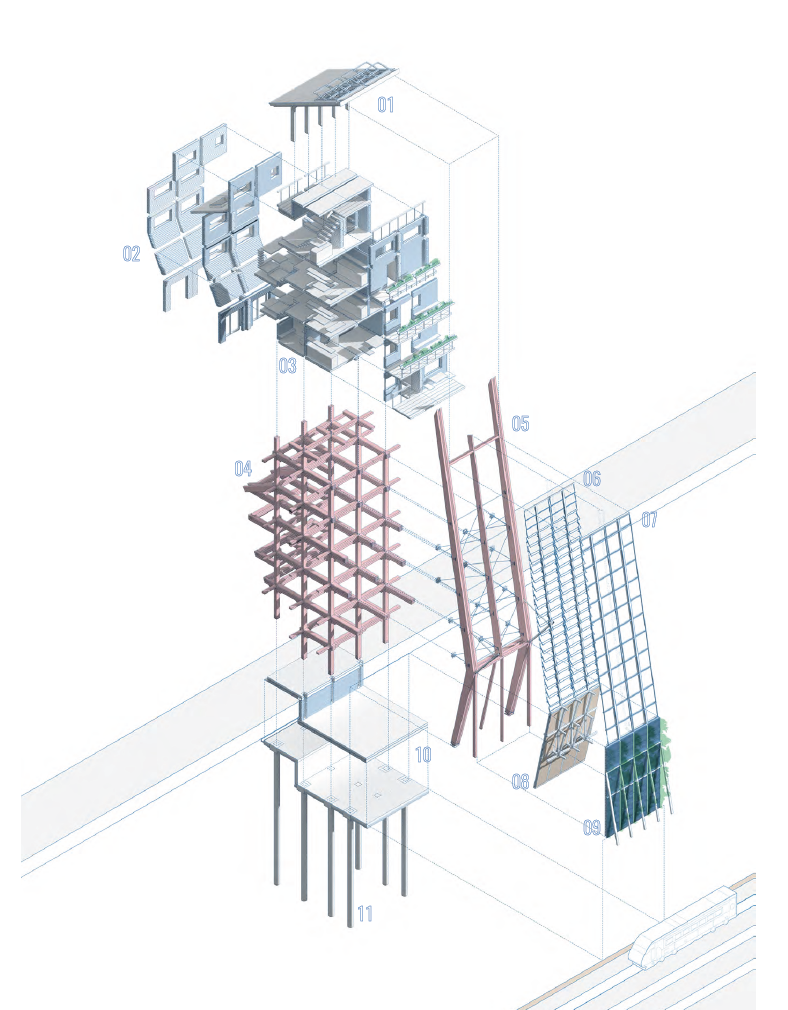

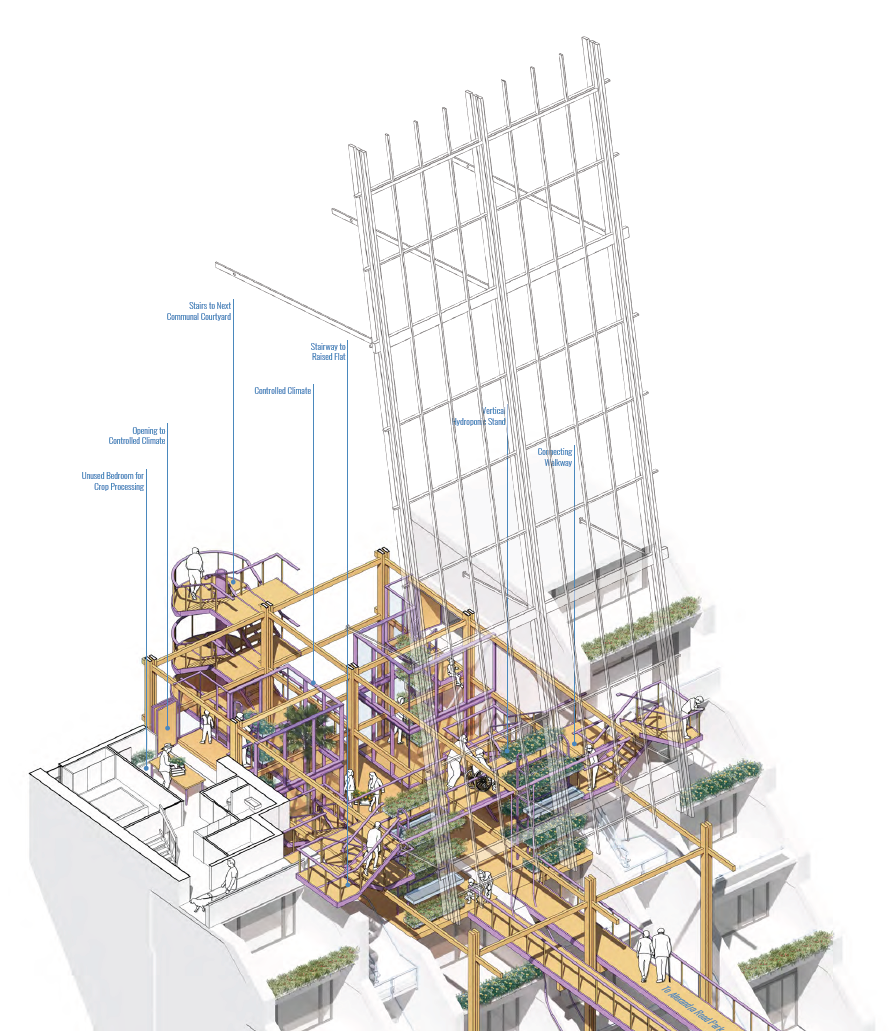

Costa del Alexandra 2050 builds upon the original council-led model to create intergenerational retirement co-housing directly across the railway (West Coast Main Line), north of Alexandra Estate. The scheme redevelops the undesirable site into a carbon-offset building for High Speed Two (HS2) powered by waste railway heat.

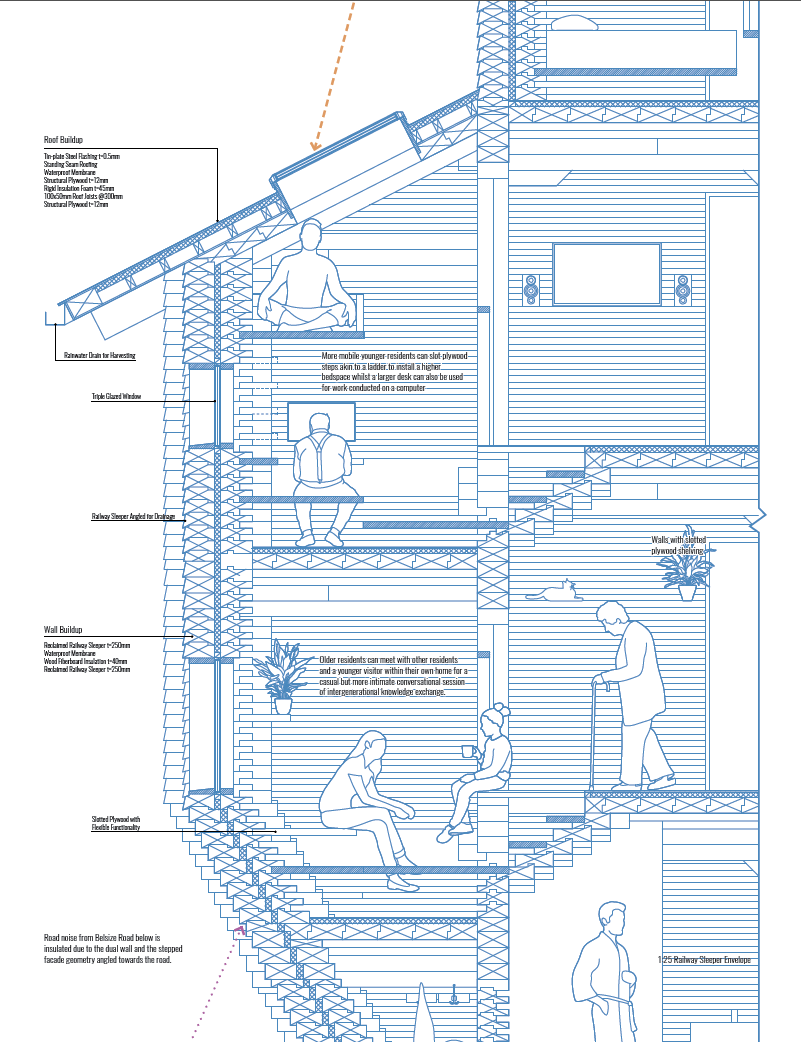

Camden Council has requested a Section 106 planning obligation for the construction of HS2 Phase 1, with HS2 Ltd. and Network Rail agreeing to contribute funds and grant land towards a Community Land Trust (CLT), formed by charity Ageing Better in Camden. Long promoting outreach to socially isolated elderly, the NGO has gathered like-minded older Kilburn residents and existing site residents to design and build “Costa del Alexandra 2050,”an active ageing co-housing community. Network Rail will provide most construction materials, from disused railway sleepers, rail-side coppice wood and cleared woodland timber from HS2’s construction, whilst the structural strategy will enhance the circular economy of materials, all to continue the carbon offsetting intent.

Here, older residents pursue an active lifestyle within a controlled microclimate, involved in daily agricultural leisure for consumption and further carbon offsetting. This will mostly occur in “communal courtyards” between residential units that host social activities including spillover gatherings, after-school programs and resident skill-sharing. Active ageing extends from basement coppice-wood workshops to rooftop greenhouses, contributing to the prolonging of lives of mutual support/care and continued carbon offsetting.

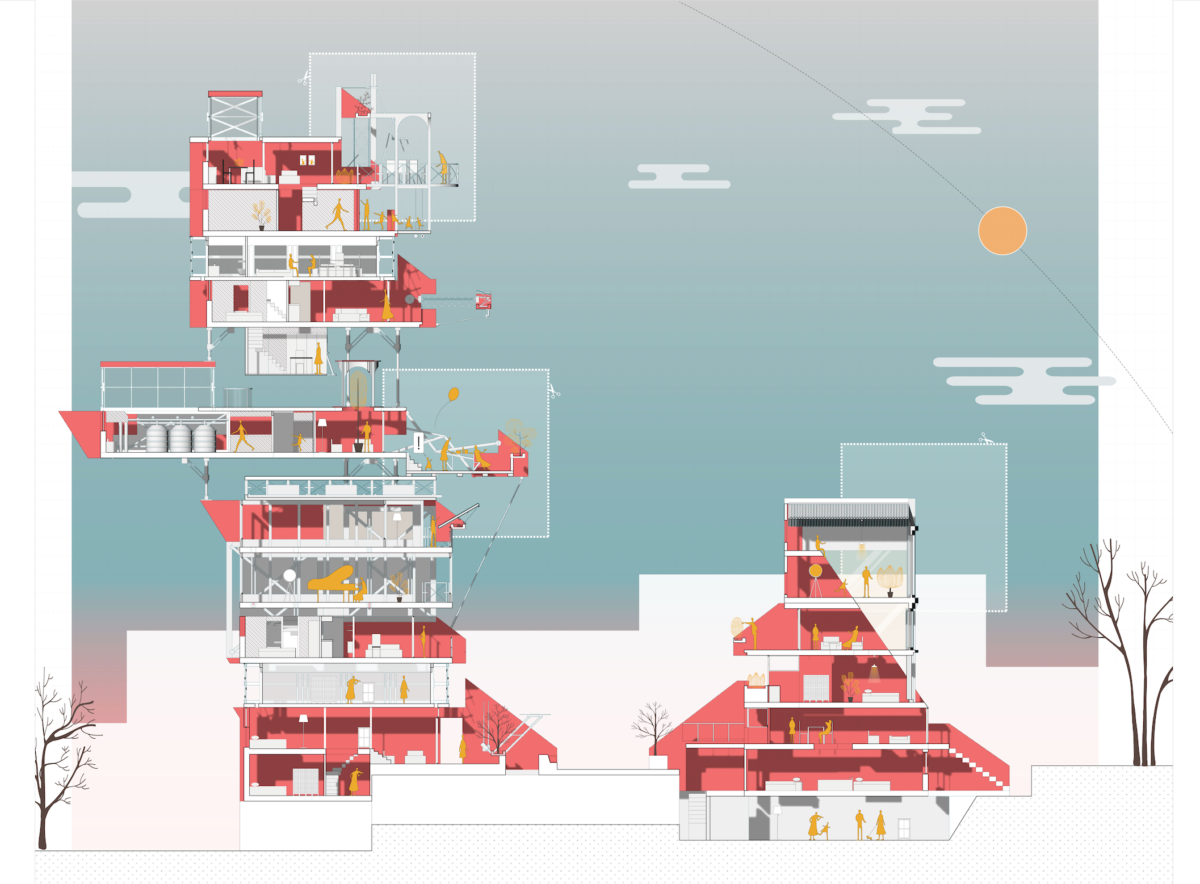

M5 Complex

Minimum Meanwhile Maximum – Movable Modules Housings

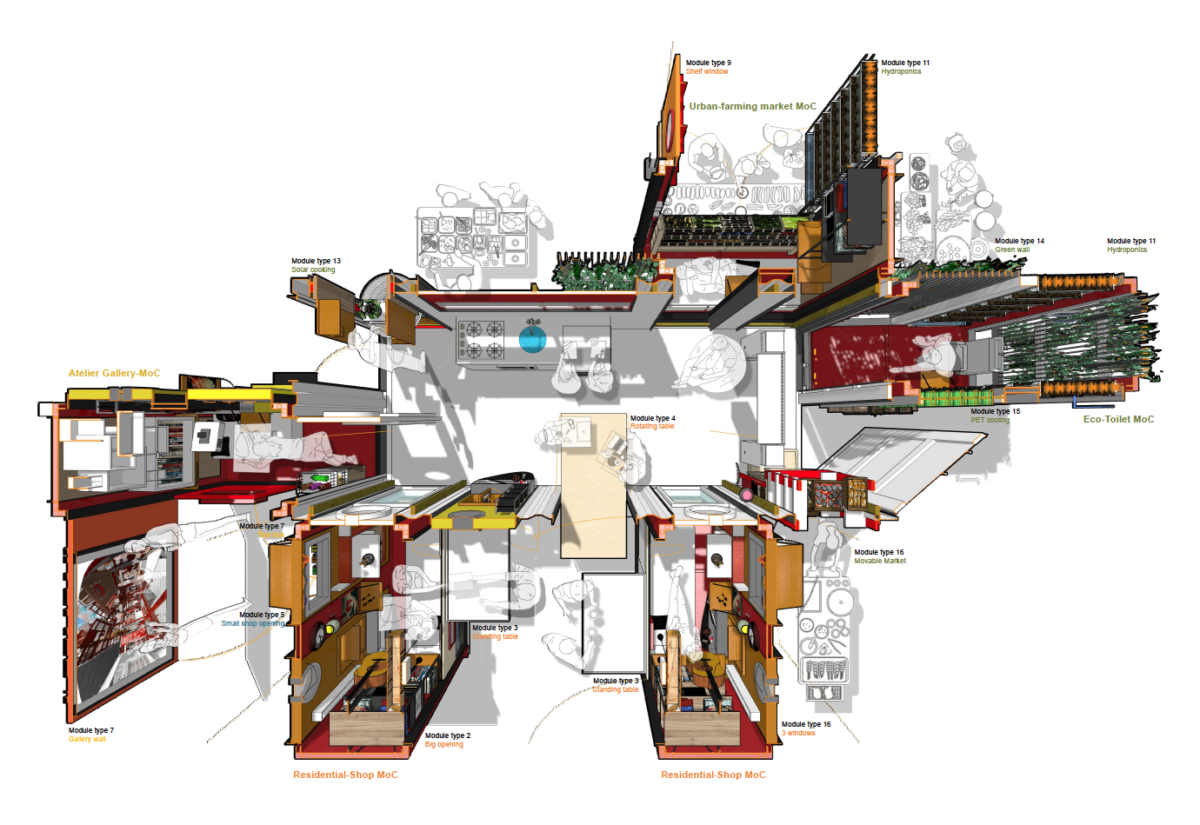

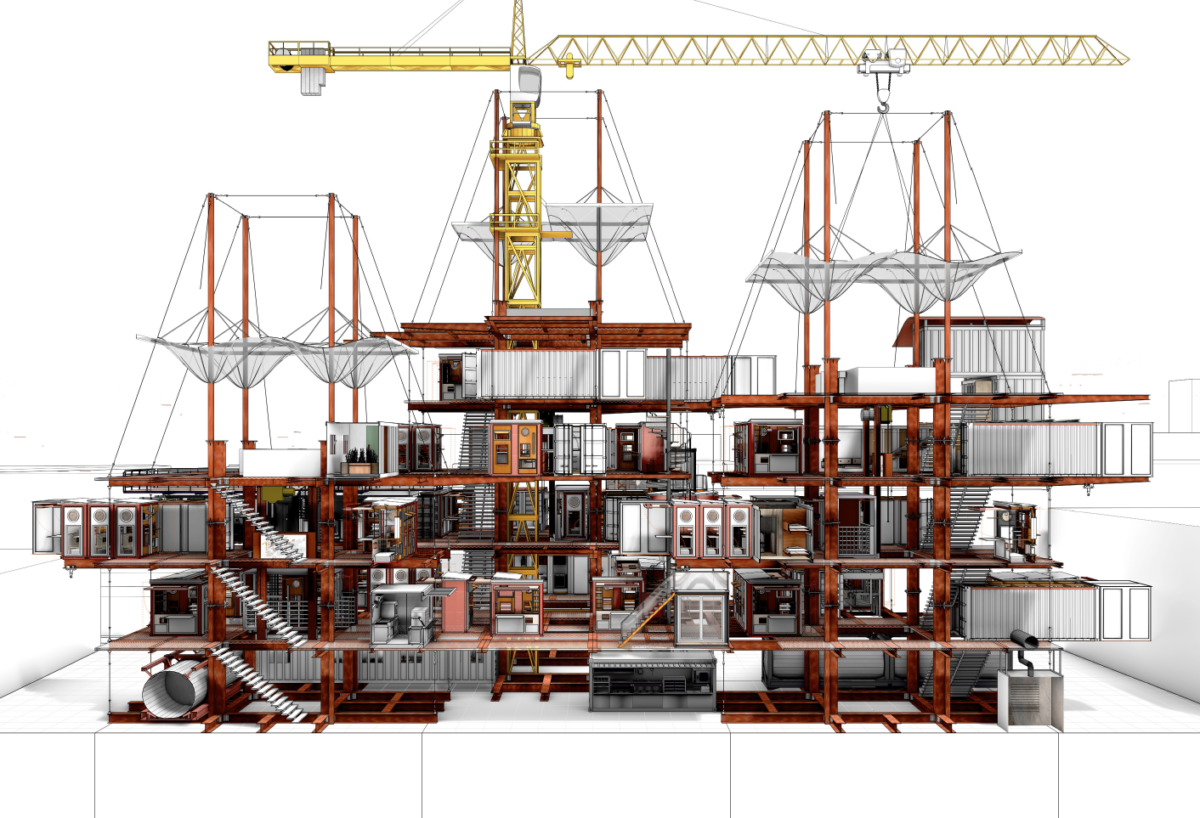

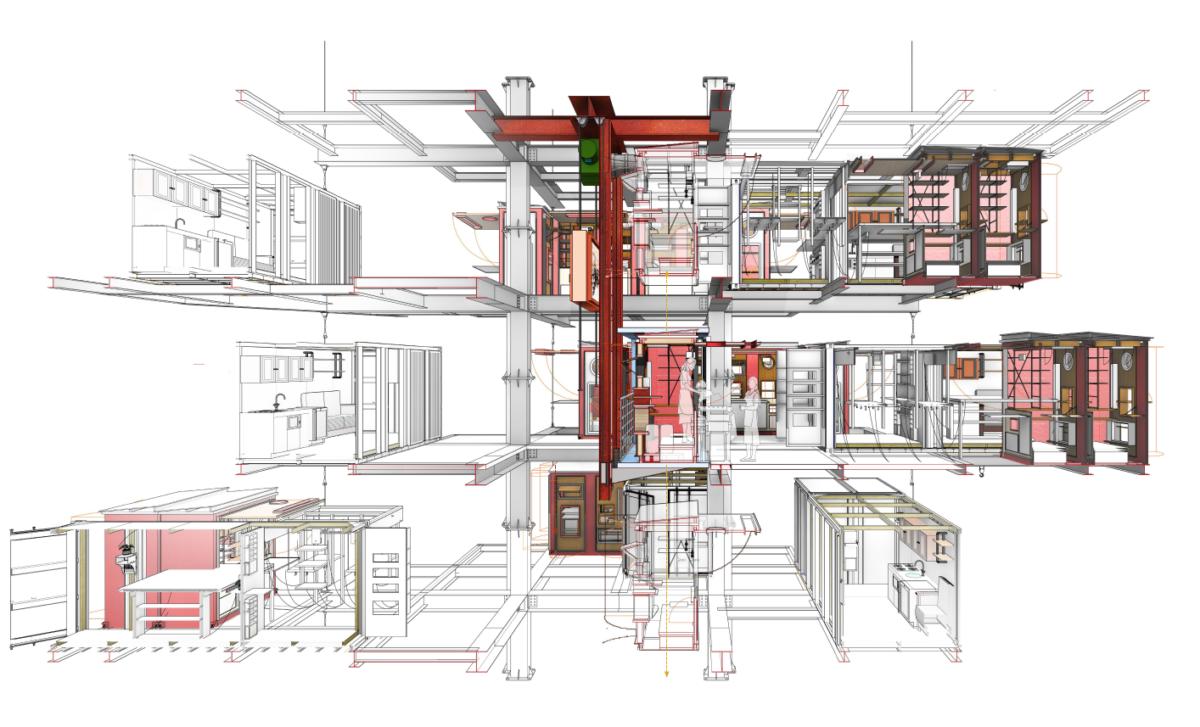

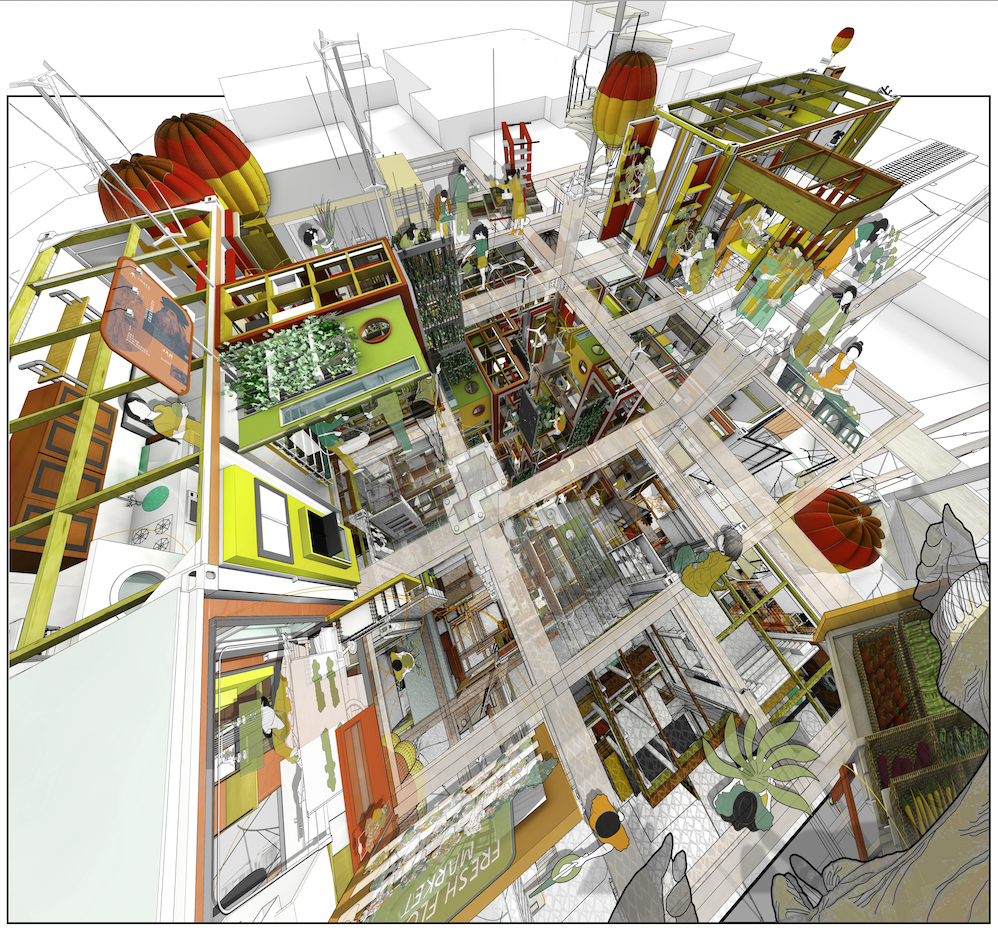

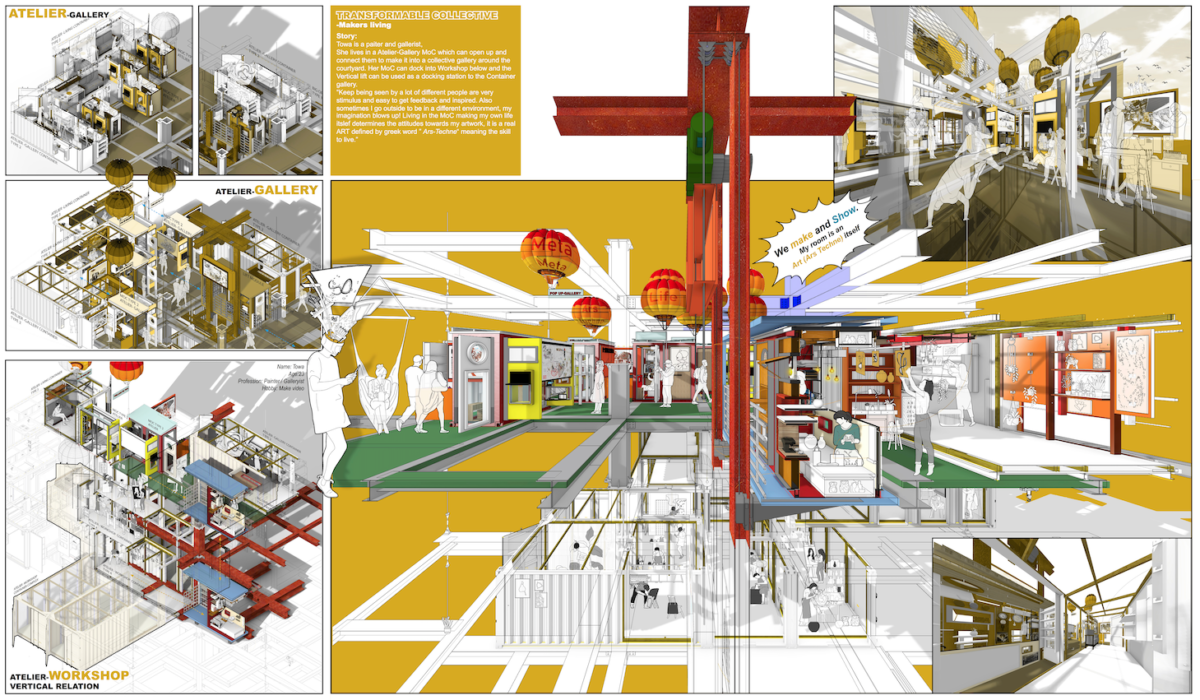

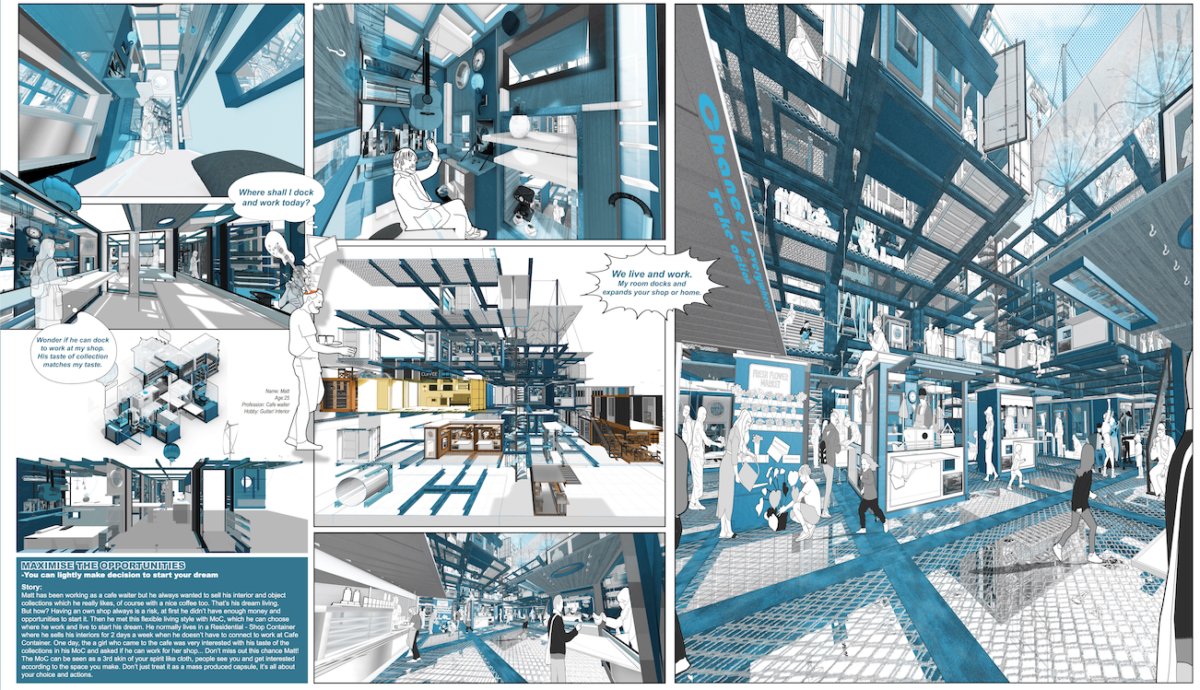

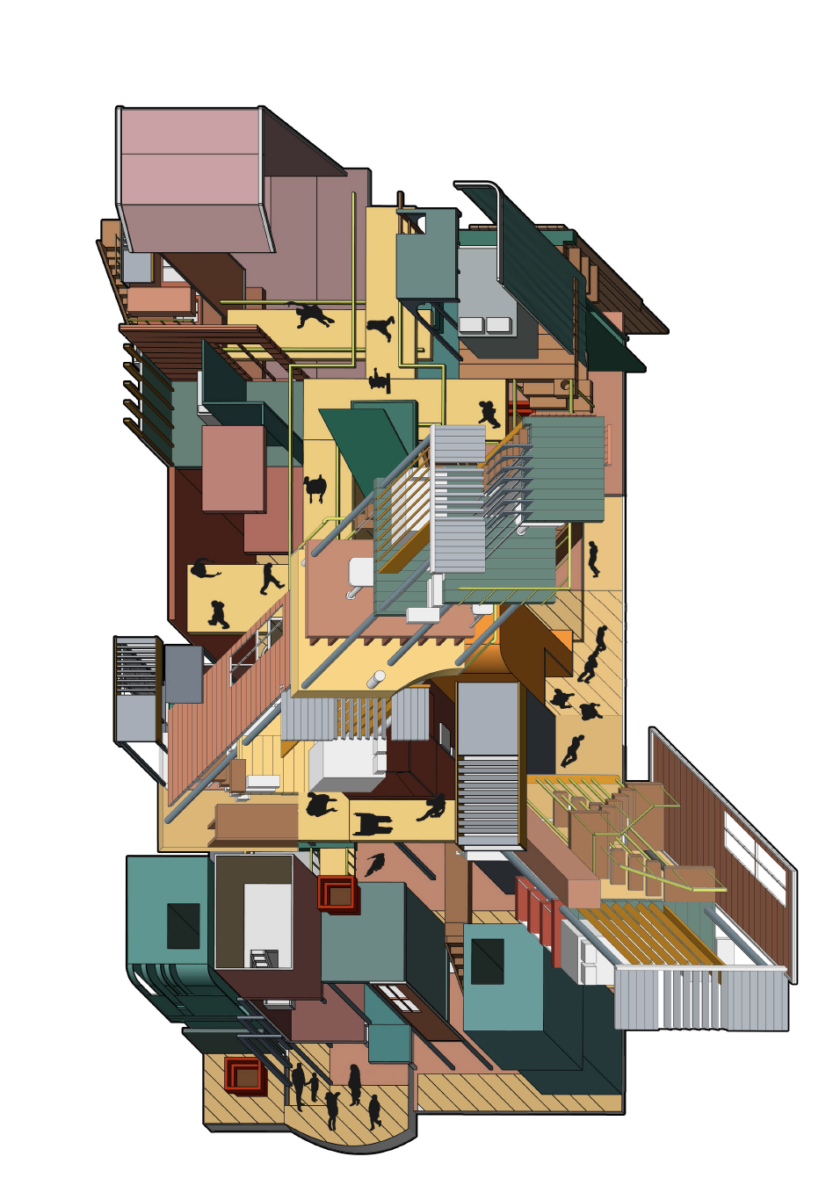

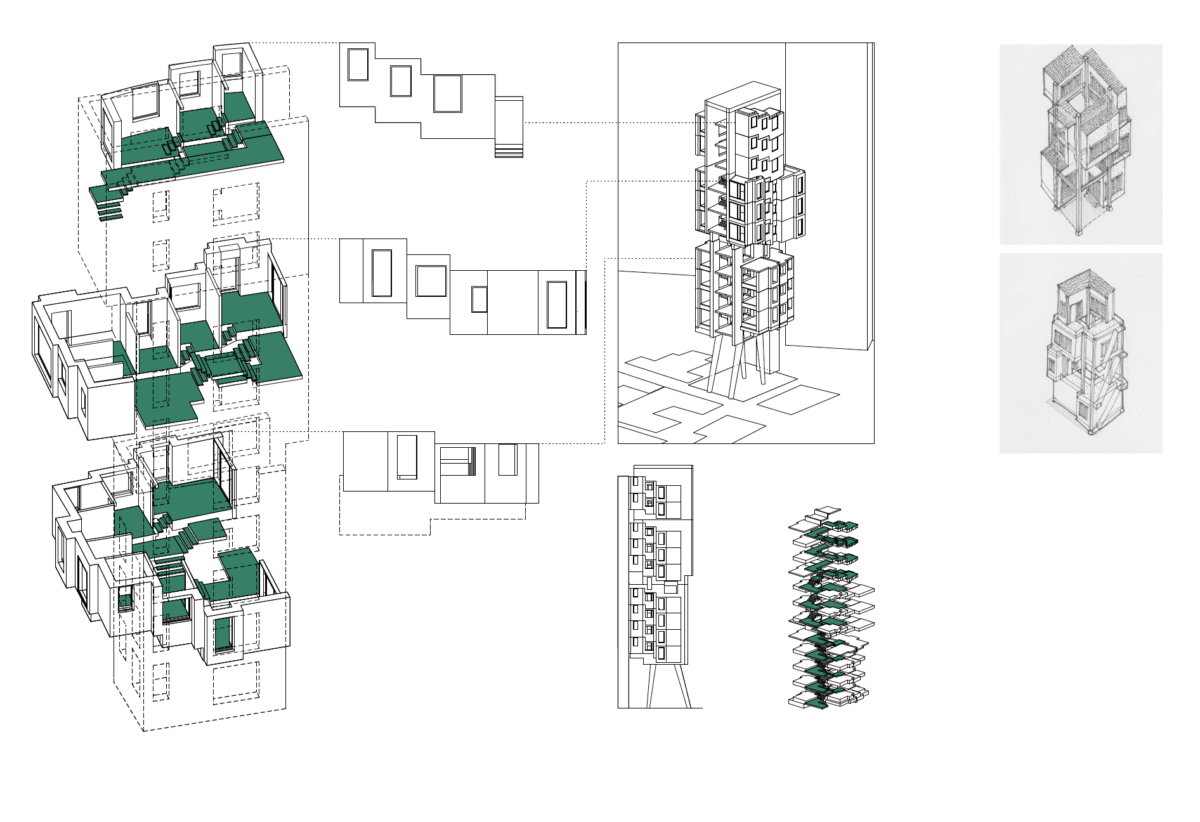

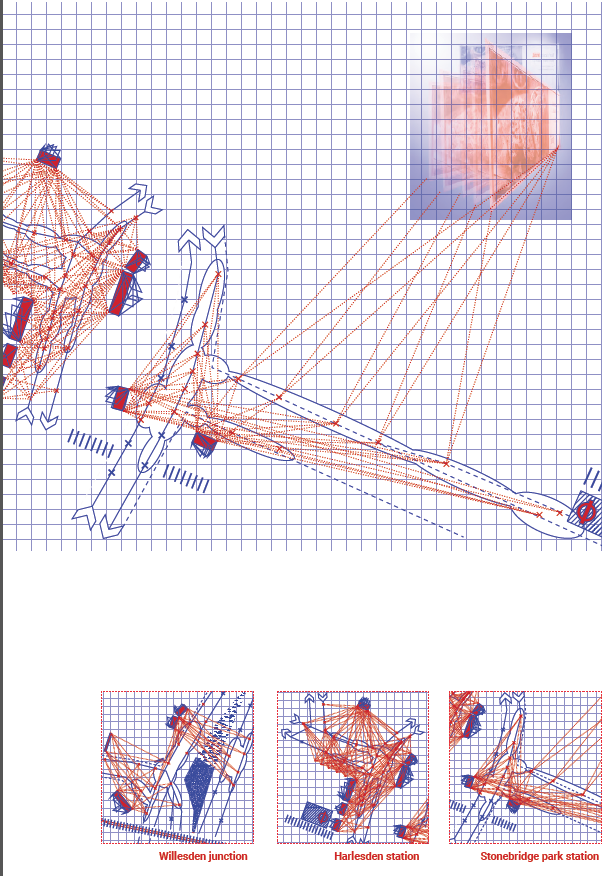

This project speculates an active and flexible way of living with the movable spaces as an utopian urban planning vision.

This project started to investigate the Odham’s walk-in Covent Garden which has got an Italian villa to feel complex consisted of only 4 different flat shapes. It has a potential relationship with the residential, communal and public shop with a courtyard typology. So this project started de-constructing the solid spatial composition, applying the movable spaces into intersections of the 2-3 spaces (Public, communal and residential).

Experimented several spatial compositions using the fragmented movable sectional drawings and combined the drawings together to make a vision of Utopian flexible housing learning from Odham’s walk.

The building is located in a small bare land next to the Hackney wick station.

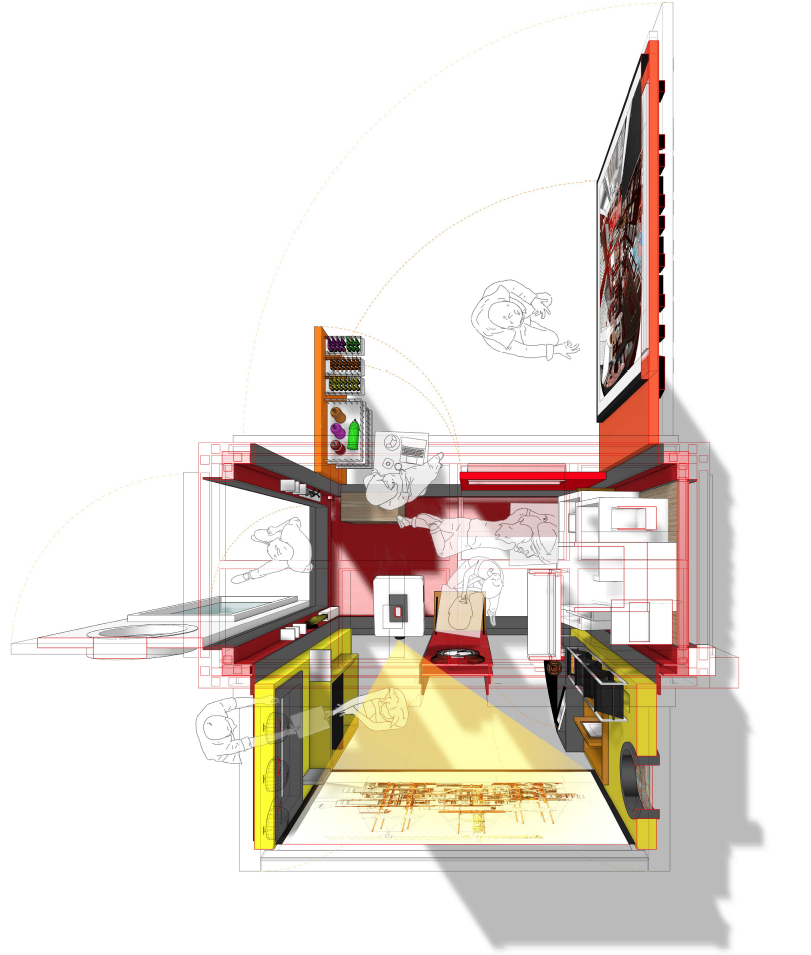

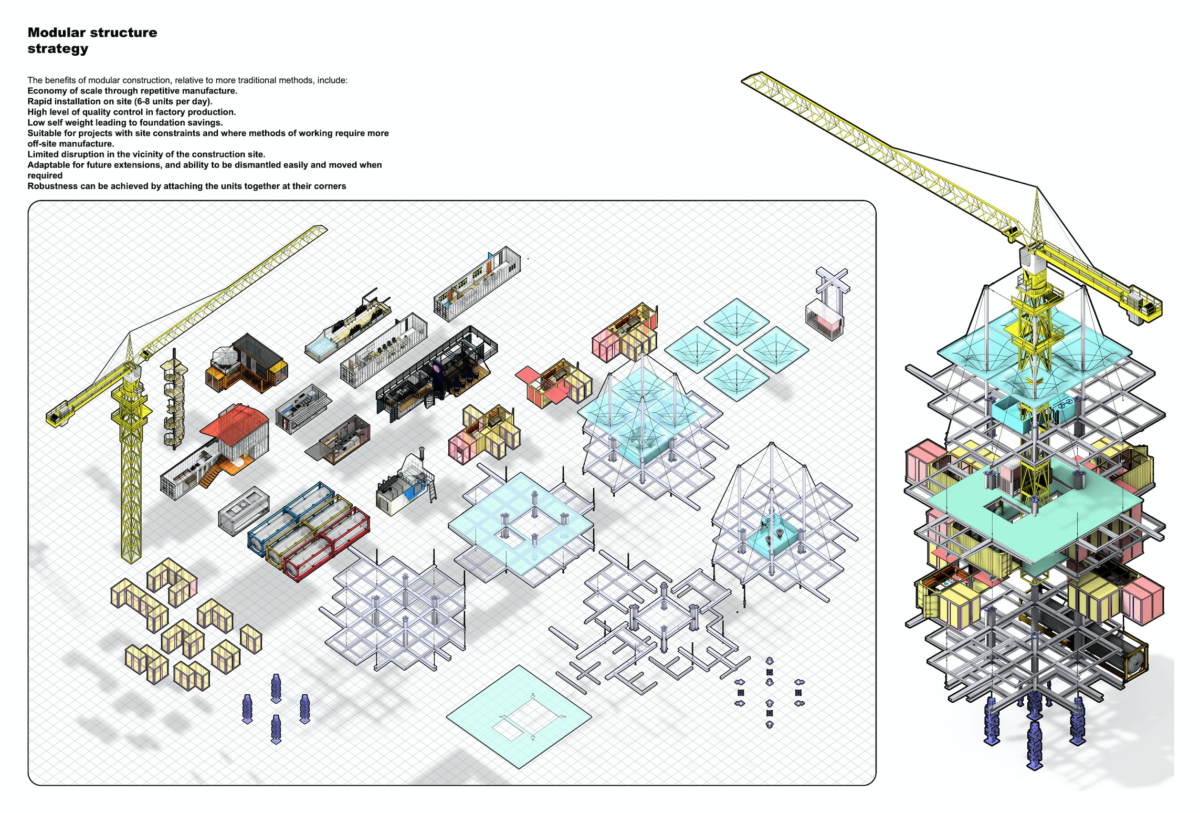

The design challenges to make a modular housing kit for the temporary living where all the components of the building being able to move away as meanwhile use and rebuild in a different land.

The building consists of 4 parts.

1: Module panels with different functions.

2: Self build movable bed unit: MoC(Mobile Cell)

3: Infrastructural movable Container-core

4: Stacking tower module-core to hang movable parts.

The building keeps moving and reconfiguring in the meanwhile spaces.

The building has a courtyard tower typology where the MoC Lift slots in to create activities to be happened around the courtyard. At the end this project suggested the catalogue of inhabitation and the comic strips to show the specific moments for different users (Young dreamer, artist/gallerist, urban farmer) with the different types of panels and combinations of the MoC and Container.

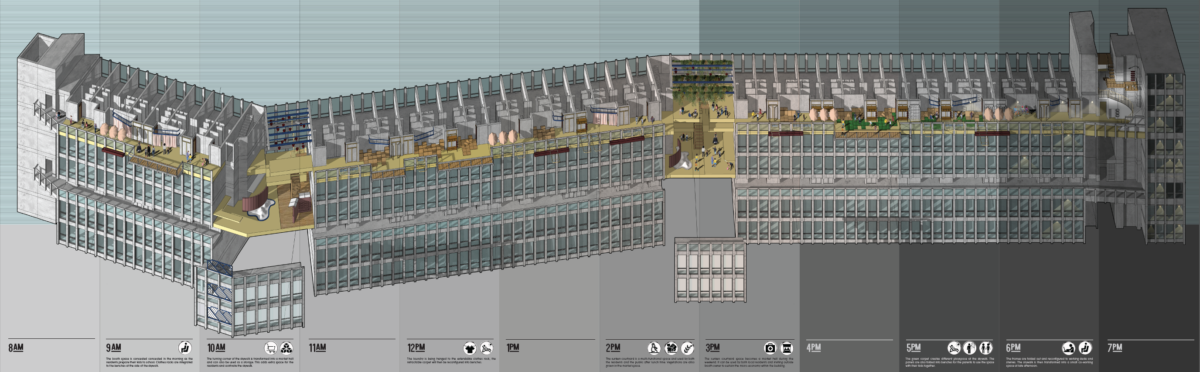

Carpeting Robin Hood Garden

The initial investigation uses Robin Hood Garden as a test bed, with the once fantasised “eye on the street” that is currently left unoccupied. The carpet at each door front sparks interest as it constructs a private boundary that exists in the public skywalk. The spatial investigation resembles the laying of carpet- it looks to inject shared spaces that accommodates domestic activities outside private boundary. The sequence of intervention is the infrastructure for these activities and is catered to different times of the day.

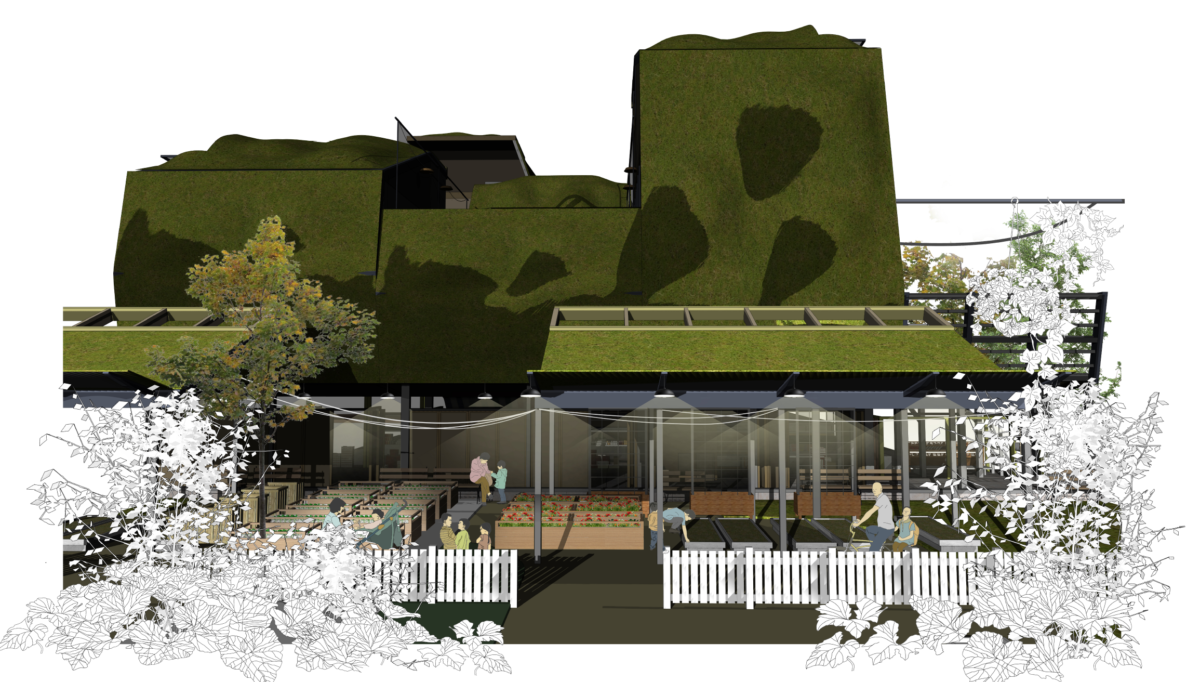

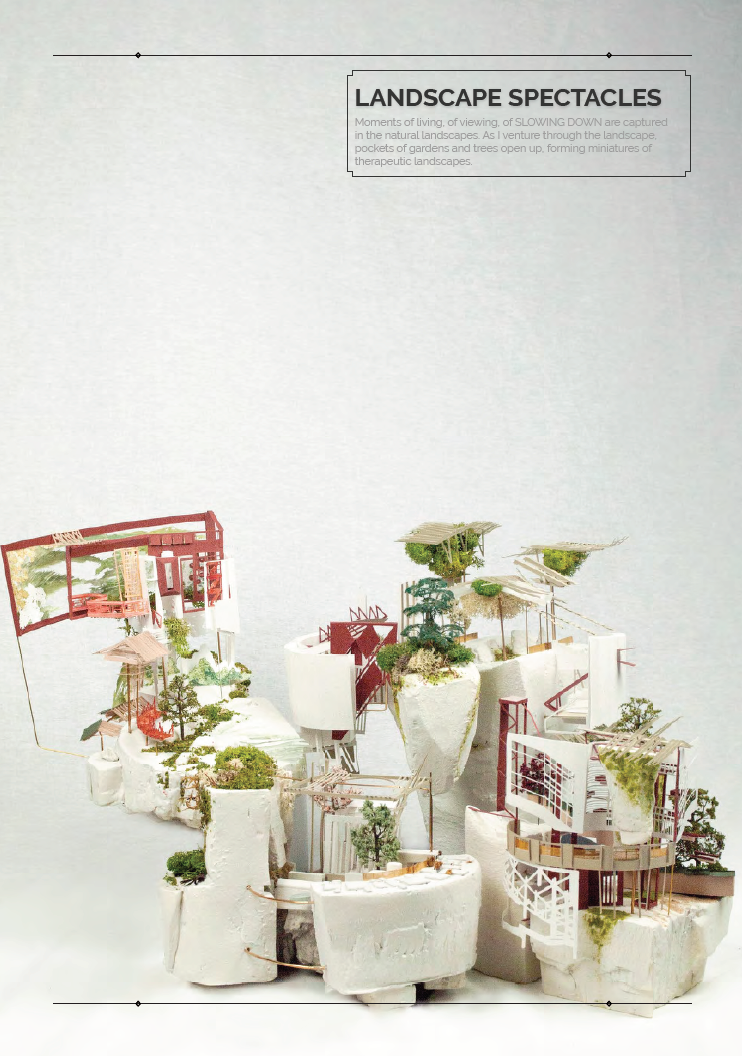

Therapeutic Landscape, Forest Gate

The ideas are then brought to the site in Forest Gate, which is considered to be the most deprived area in Britain. The project revives its legacy as a therapeutic location- From its origin in the 18th century as the gate of “the People’s Forest”, a retreat where thousands of commoners shared rights to graze cattle during the weekends.

The design questions the front-and-back relationship of the Victorian house and its back-garden. The therapeutic landscape creates a new village typology that blends into its surrounding Victorian House. The New Commoner’s Dwelling is sandwiched between the ground floor market and shared kitchen, and the roof communal garden. These become a matrix of spaces, where shared space interweaves with private space at different levels. The blurring of domesticity with communal programs creates a living and social arena that enhances neighborhood relationship.

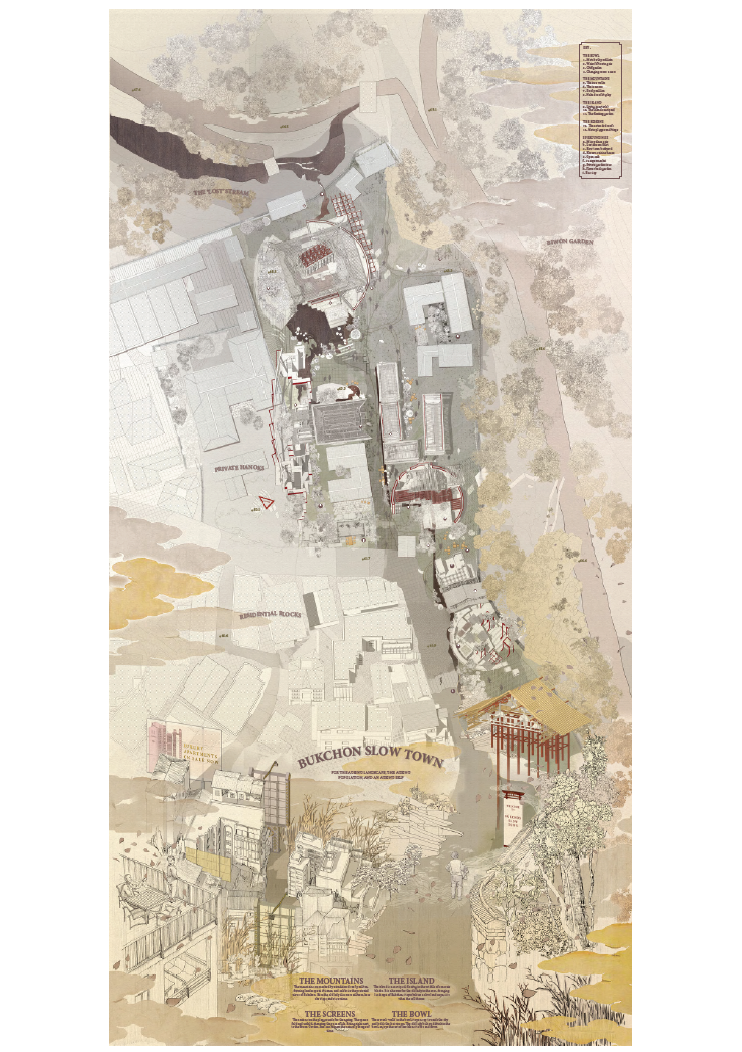

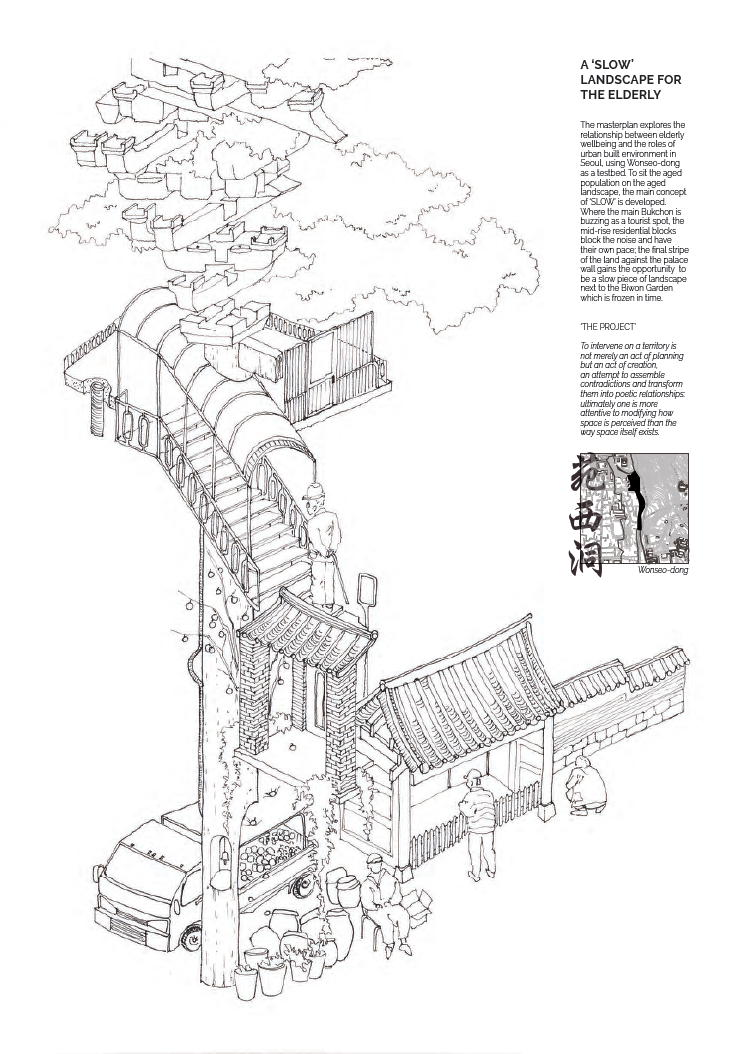

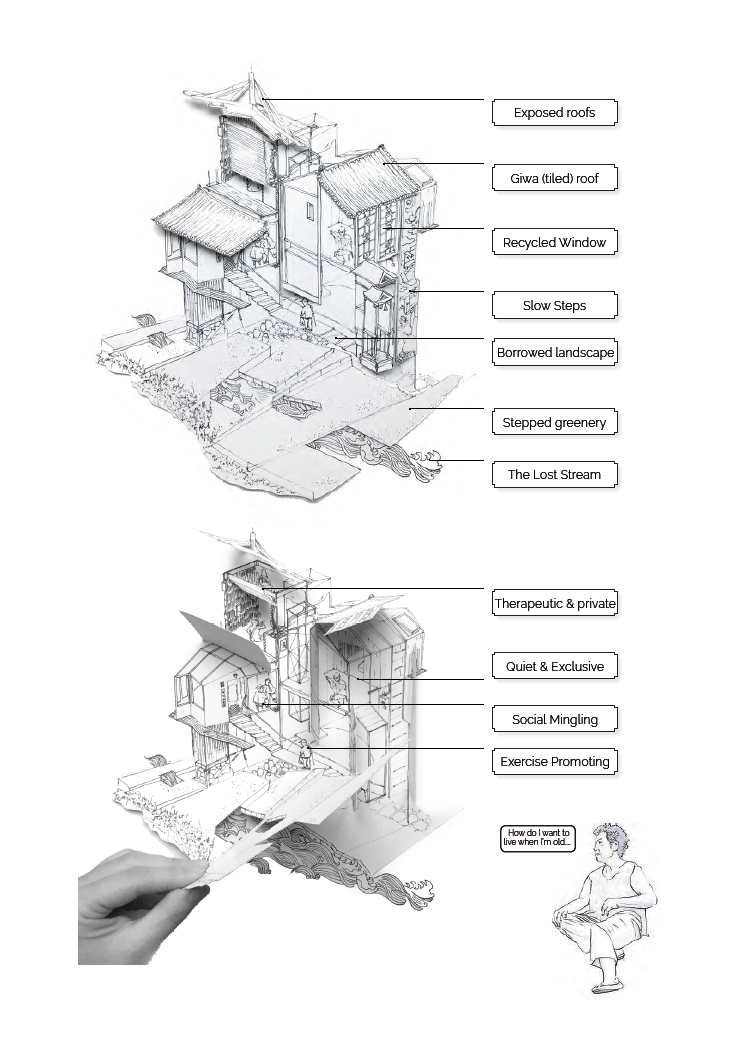

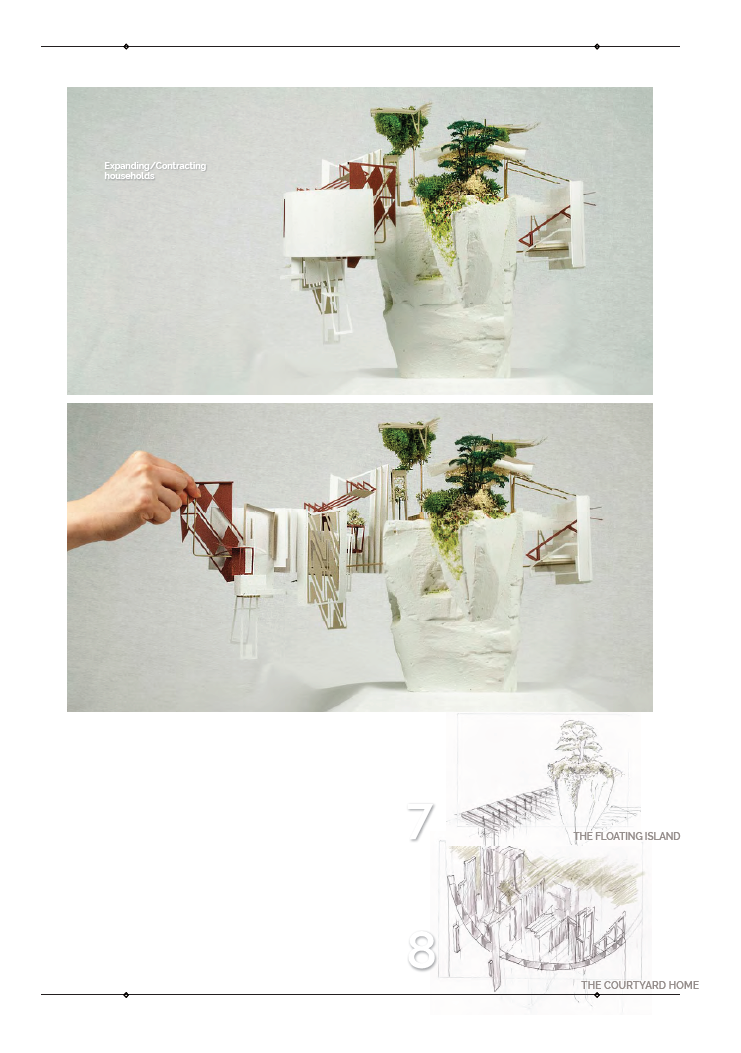

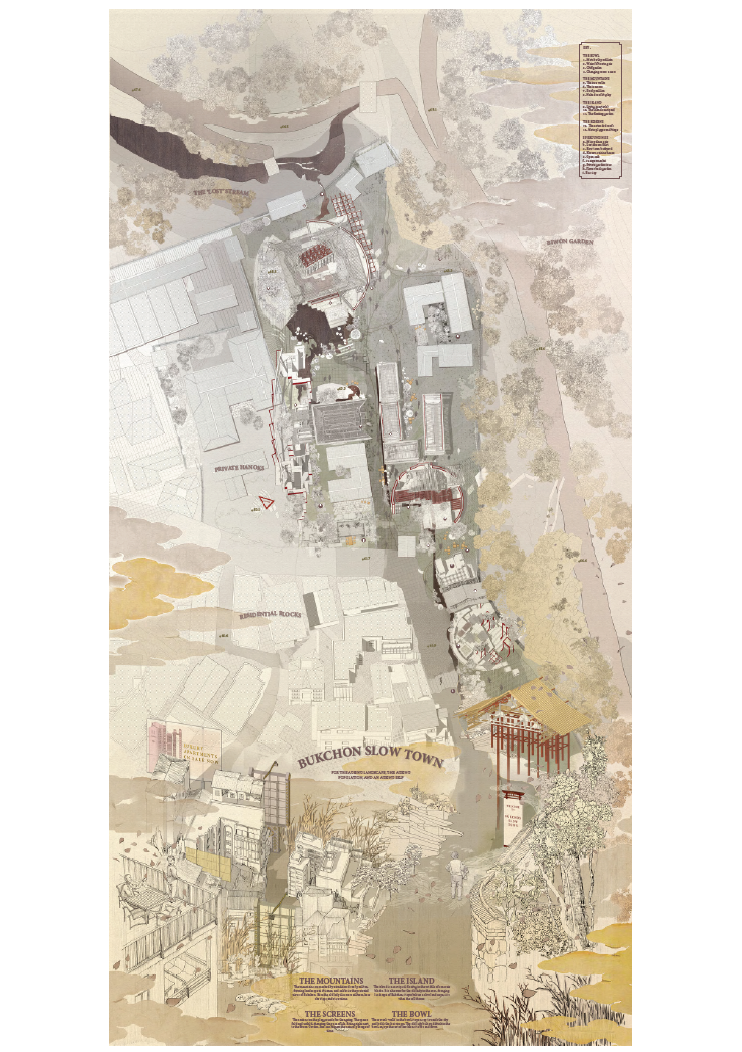

Bucheon Slow Town

An urban island for an ageing population

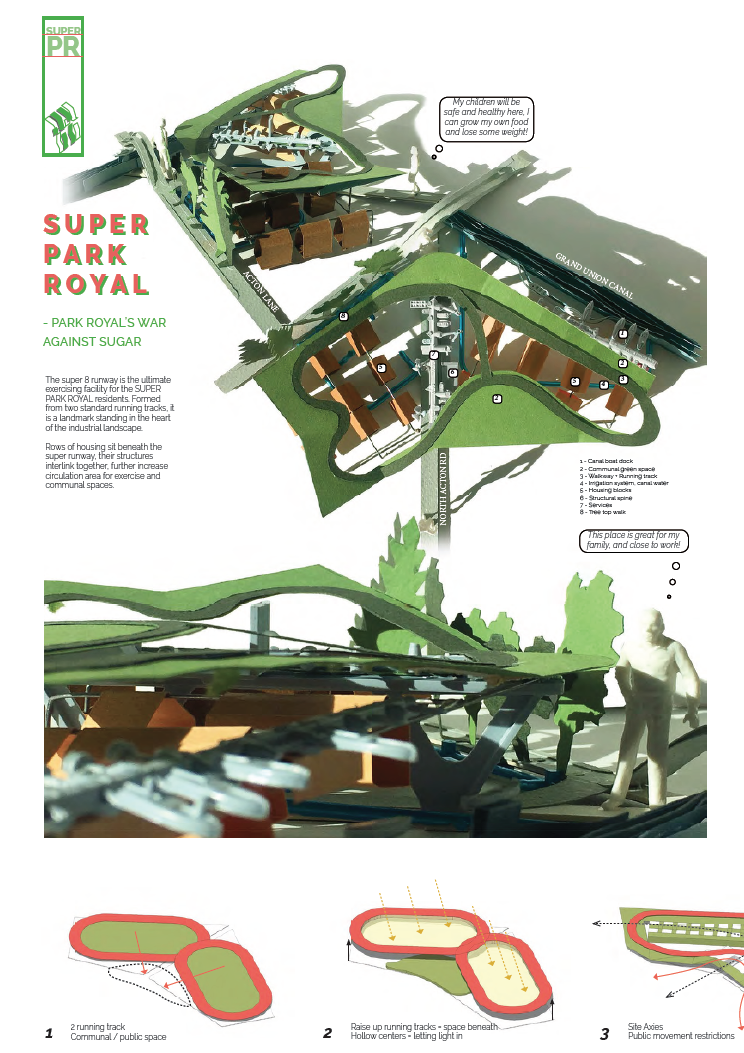

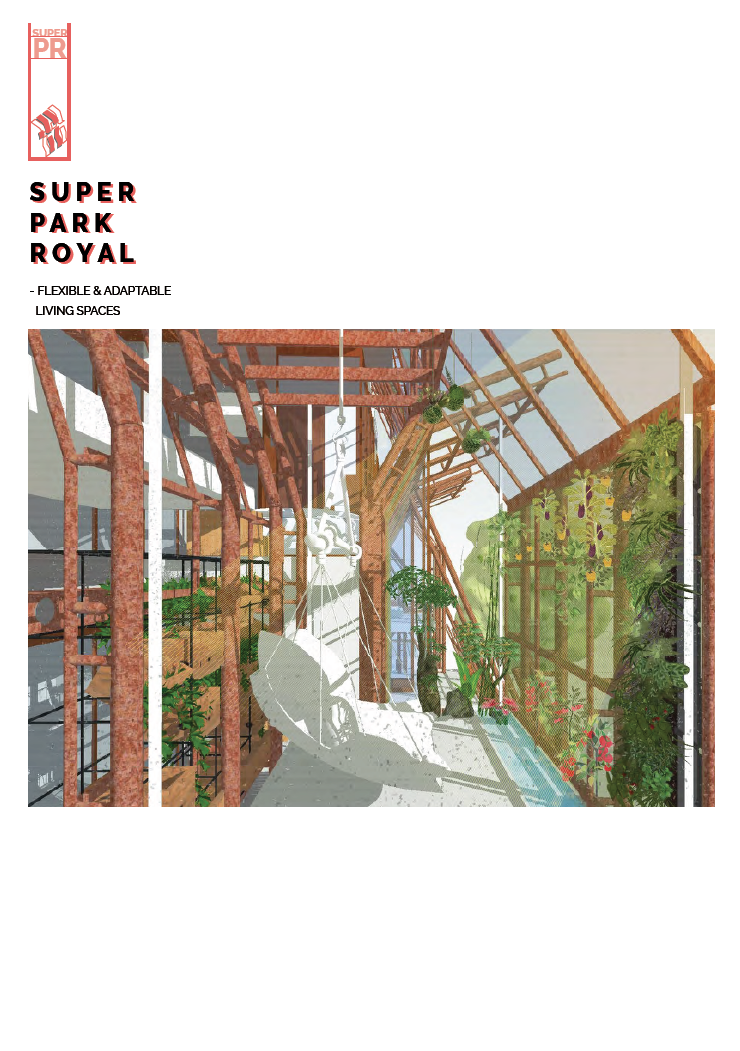

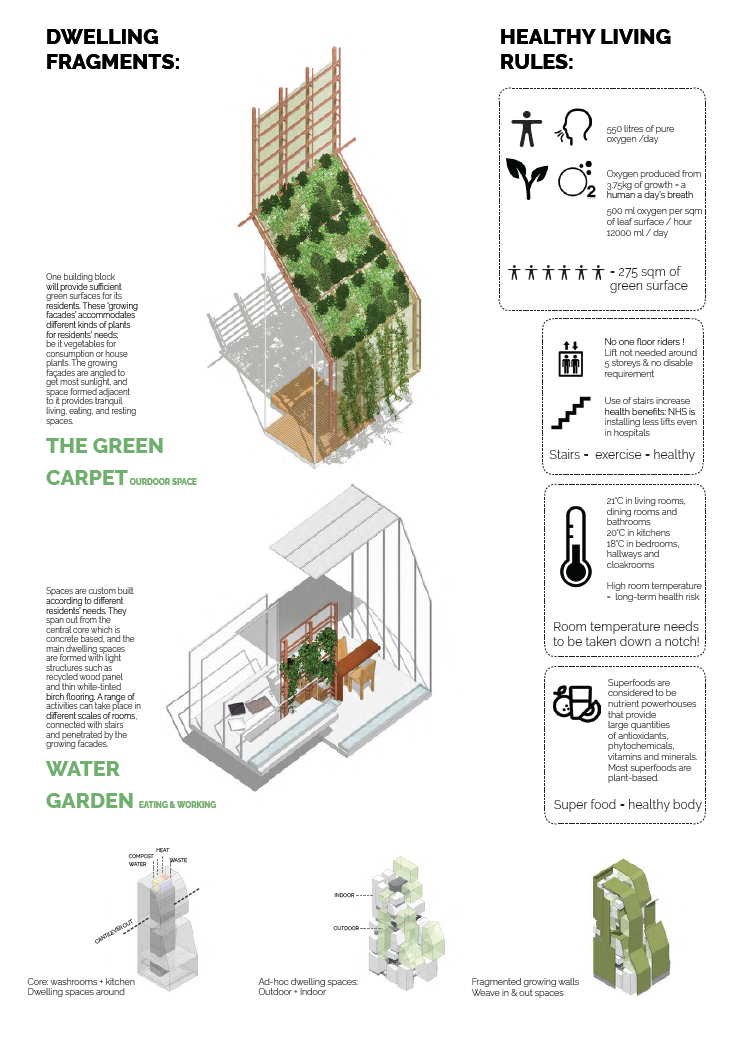

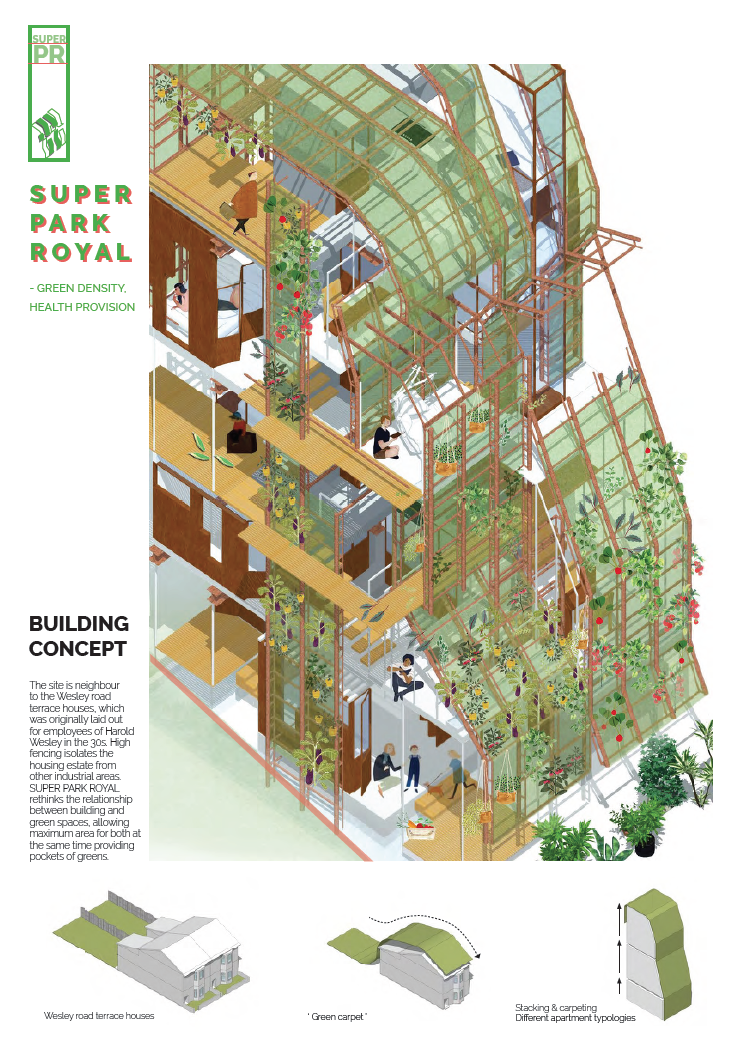

Super Park Royal

Beebreeder Competition

(RE) Placing the Urban Hanok

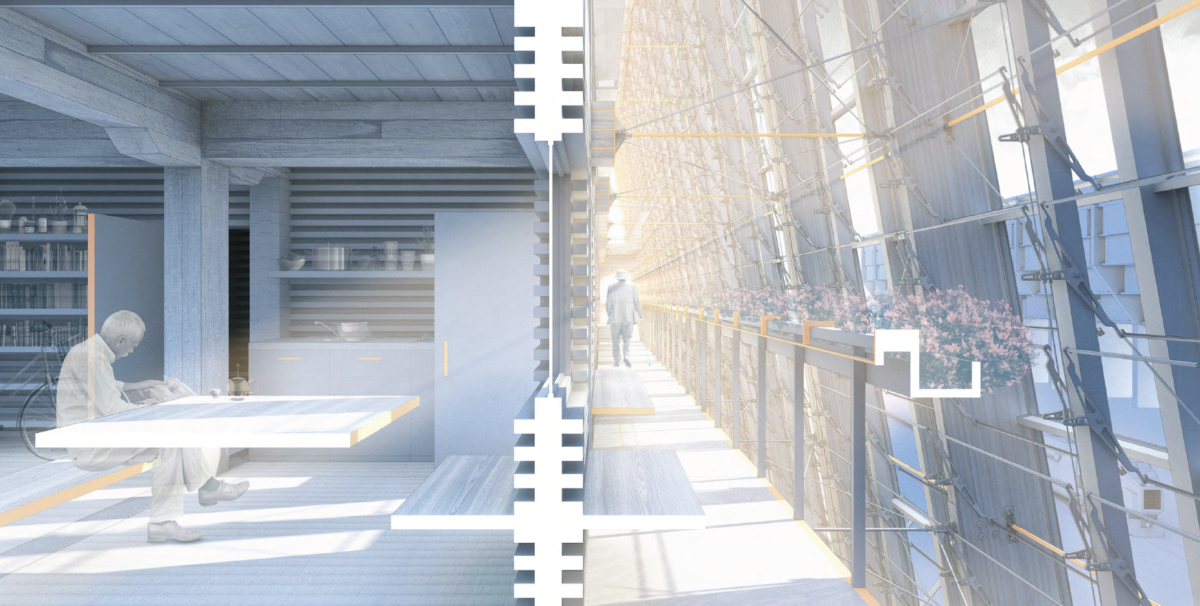

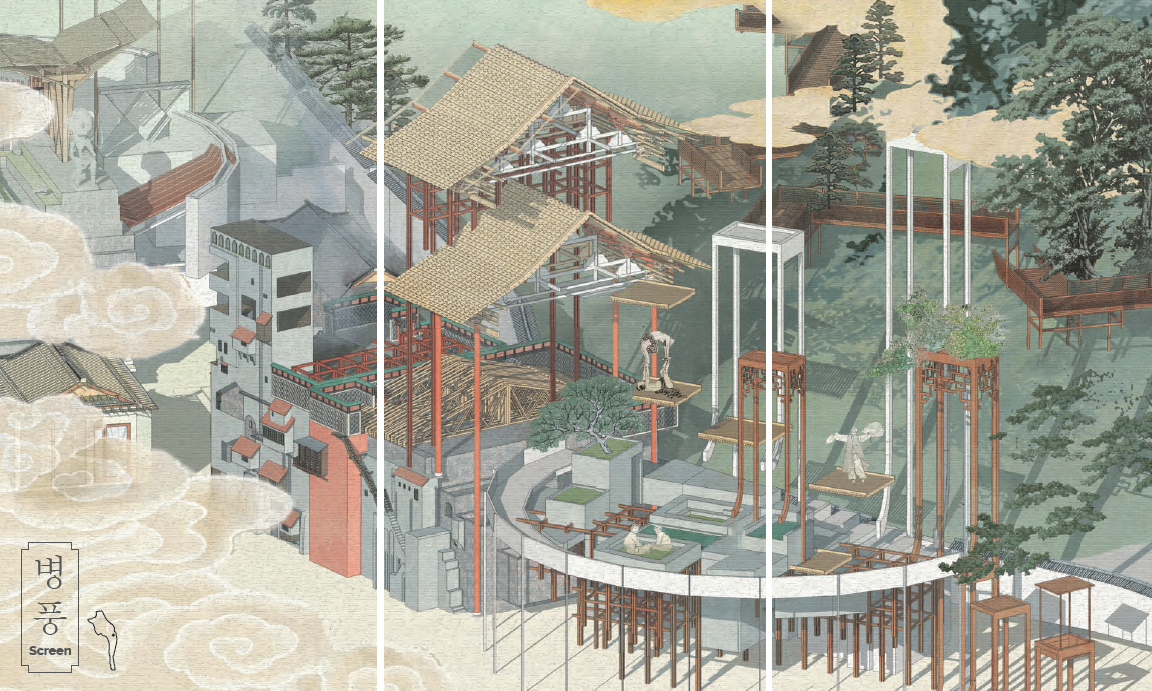

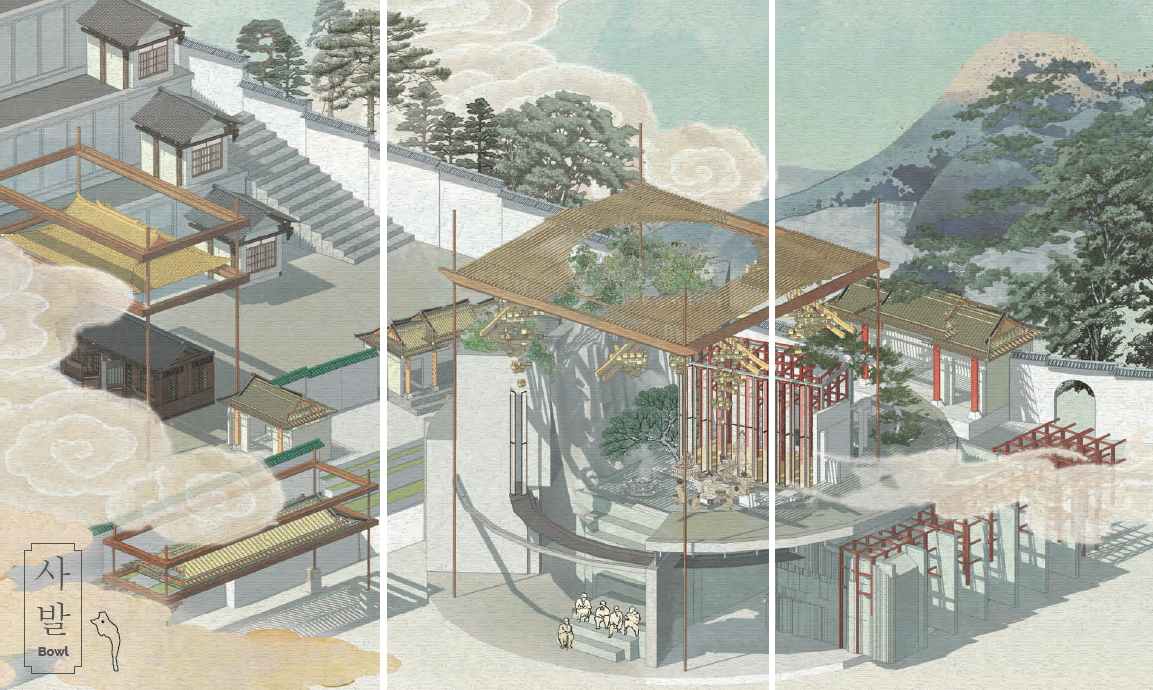

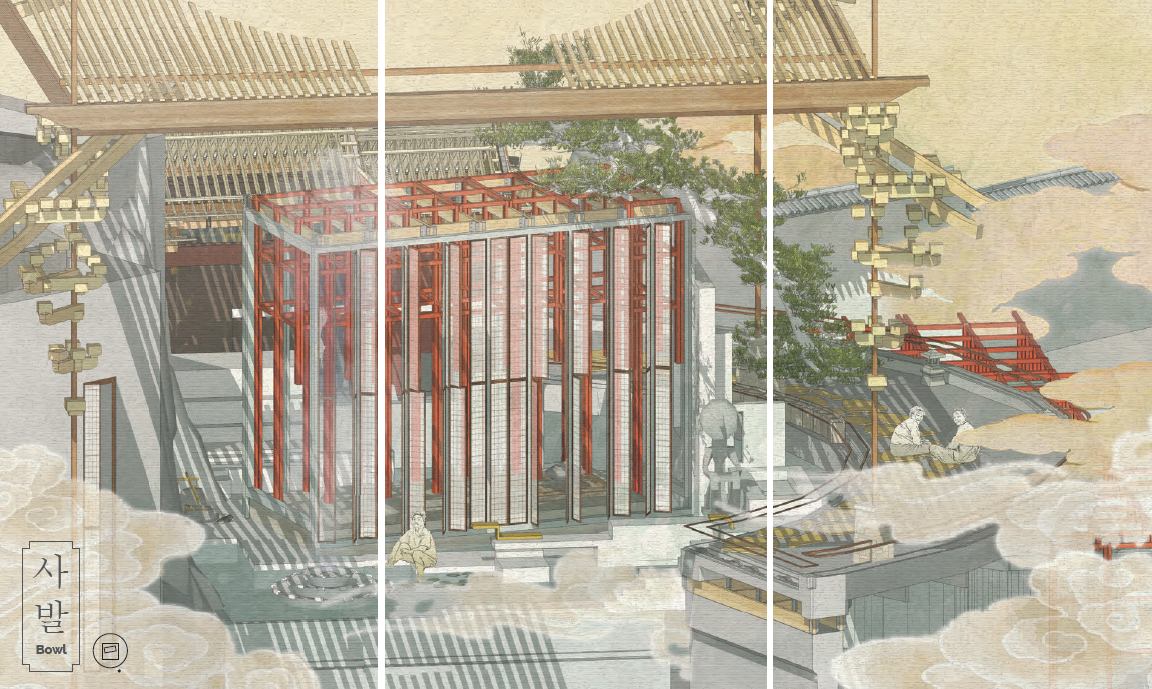

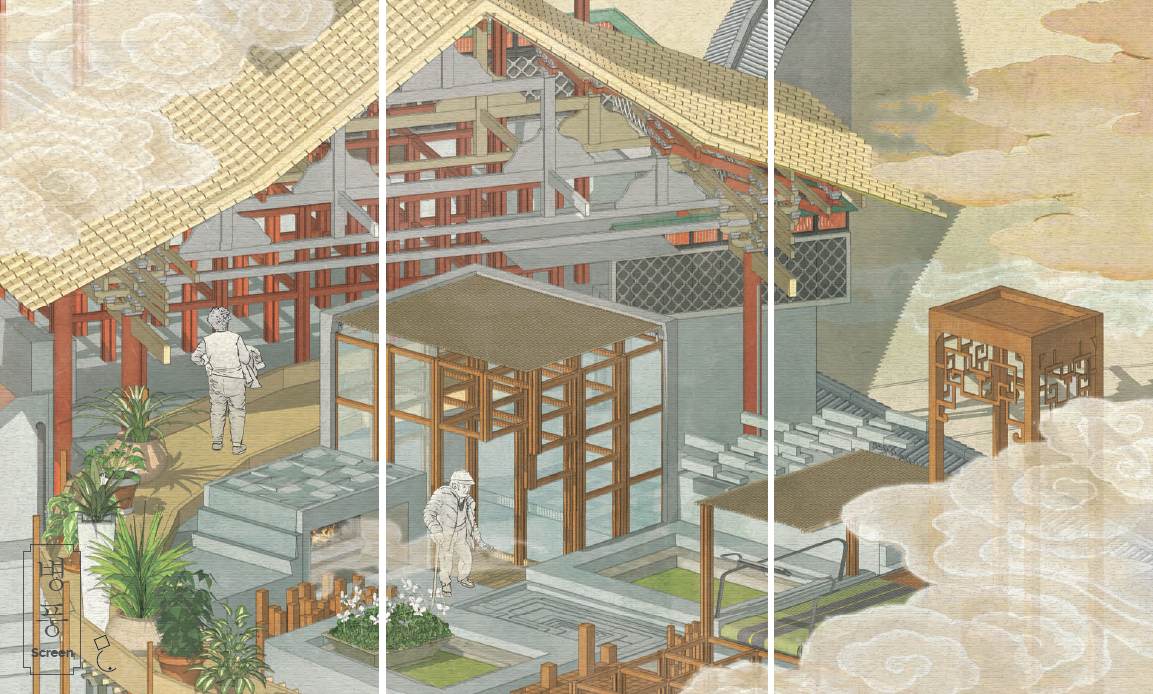

This project sets out to question the position of historic housing stock within cities which have rapidly developed since its original construction. It highlights a current global phenomenon that residential areas of historic value, which are often located in premium locations in developed cities, have become expensive, tourist-orientated neighbourhoods. Focusing on Seoul’s historic urban courtyard typology and the context in which it emerged in the 1930s, as well as the current environment in which it exists, the project discusses how contextual change results in a changed relevance of historic housing.

Focusing on Seoul’s remaining urban hanok neighbourhoods, the project investigates preservation strategies that have resulted in the majority of the city’s historic housing stock being rebuilt. The project employs Eunpyeong Hanok Village as a case study to investigate the Seoul Metropolitan Governments method of constructing entirely new urban hanok villages as a way of preserving the housing typology.

The project attempts to re-evaluate recognised approaches for urban development and preservation. It highlights a current tendency of urban preservation strategies resulting in the creation of exclusive and expensive contemporary neighbourhoods. It raises a question at a global scale of whether there is an alternative approach, where historic housing can be adapted in order to benefit local communities, and used as a site for additional affordable housing.

The project rejects theories on preservation which emphasise material originality and replicating aesthetic appearance. Instead, it focuses on the importance of preserving the social qualities and ideas on domestic space embedded within housing. It identifies the city as a fluid system which is continually and incrementally changing. Historic housing stock should therefore be allowed to adapt and change to different contexts and new generations of inhabitants.

As shown in Seoul, rapid urban development can force a city to re-evaluate its historic housing stock. Surrounded by newer, taller and modernised developments, historic housing stock can appear outdated.

If historic housing stock is not reinvented within new contexts, it risks becoming irrelevant. It may be demolished and replaced with something new – as with the urban hanoks over the past 50 years – or preserved and converted into an exclusive typology, beneficial for tourism or a privileged few.

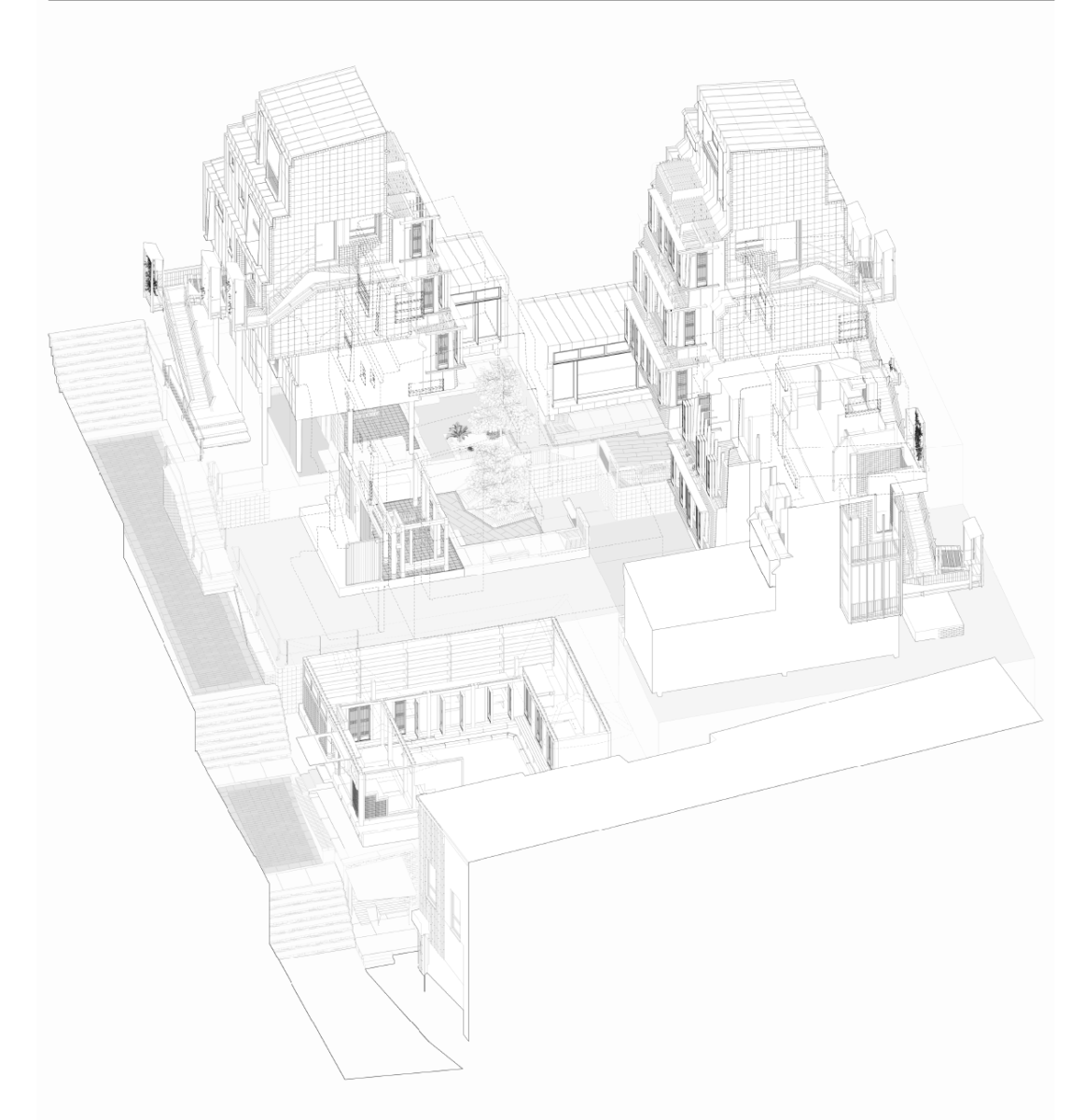

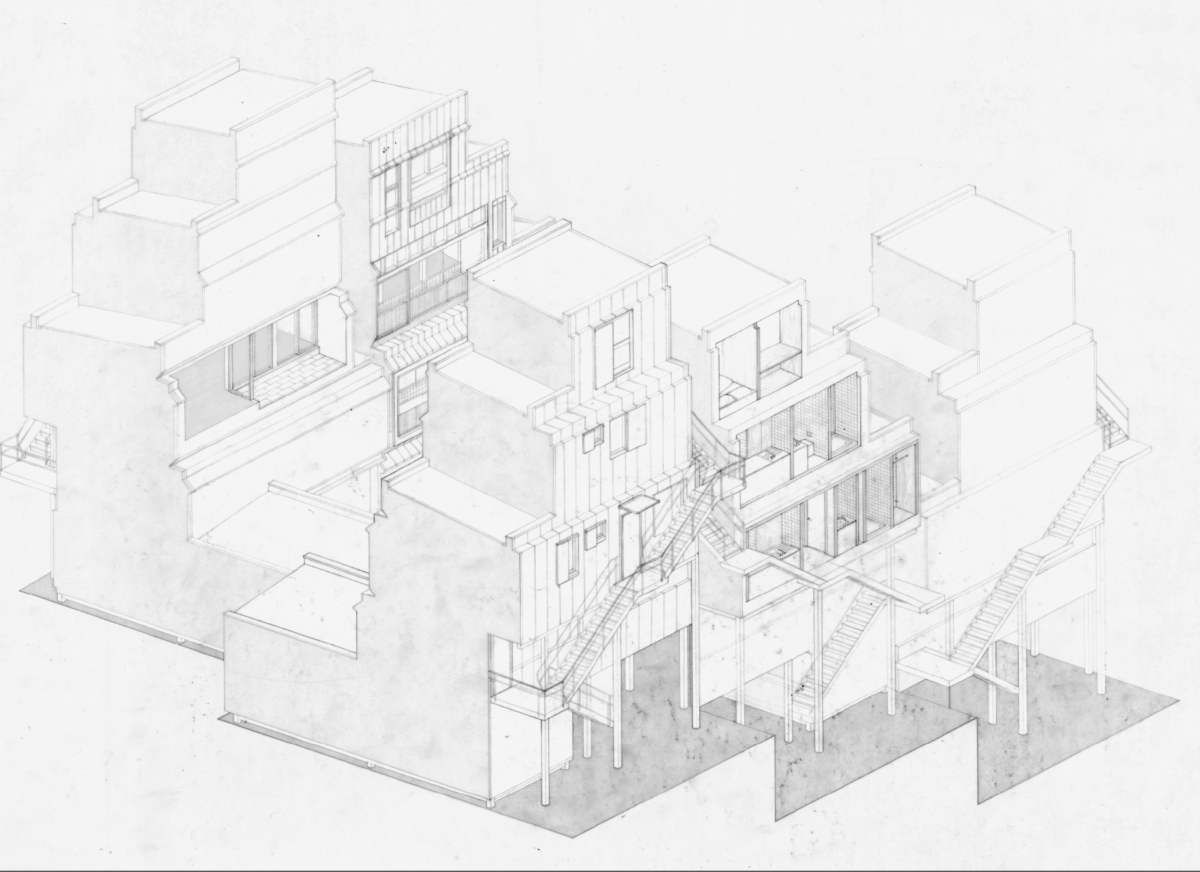

The project speculates on how housing design can be allowed to evolve. It does this by studying the existing condition of the urban hanok is terms of its structural and spatial design as well how it has been adapted and appropriated by residents. The design then provides a higher density typology which introduces contemporary construction methods and ideas on inhabitation, while retaining a layout influenced by the original urban hanok form.

The design provides an example of a reinvented typology that responds to the contextual needs of the present day. It also demonstrates how housing can be additively changed on a plot-by-plot basis. It opposes both a broad master-planned re-development of an area, or preserving a neighbourhood as a whole.

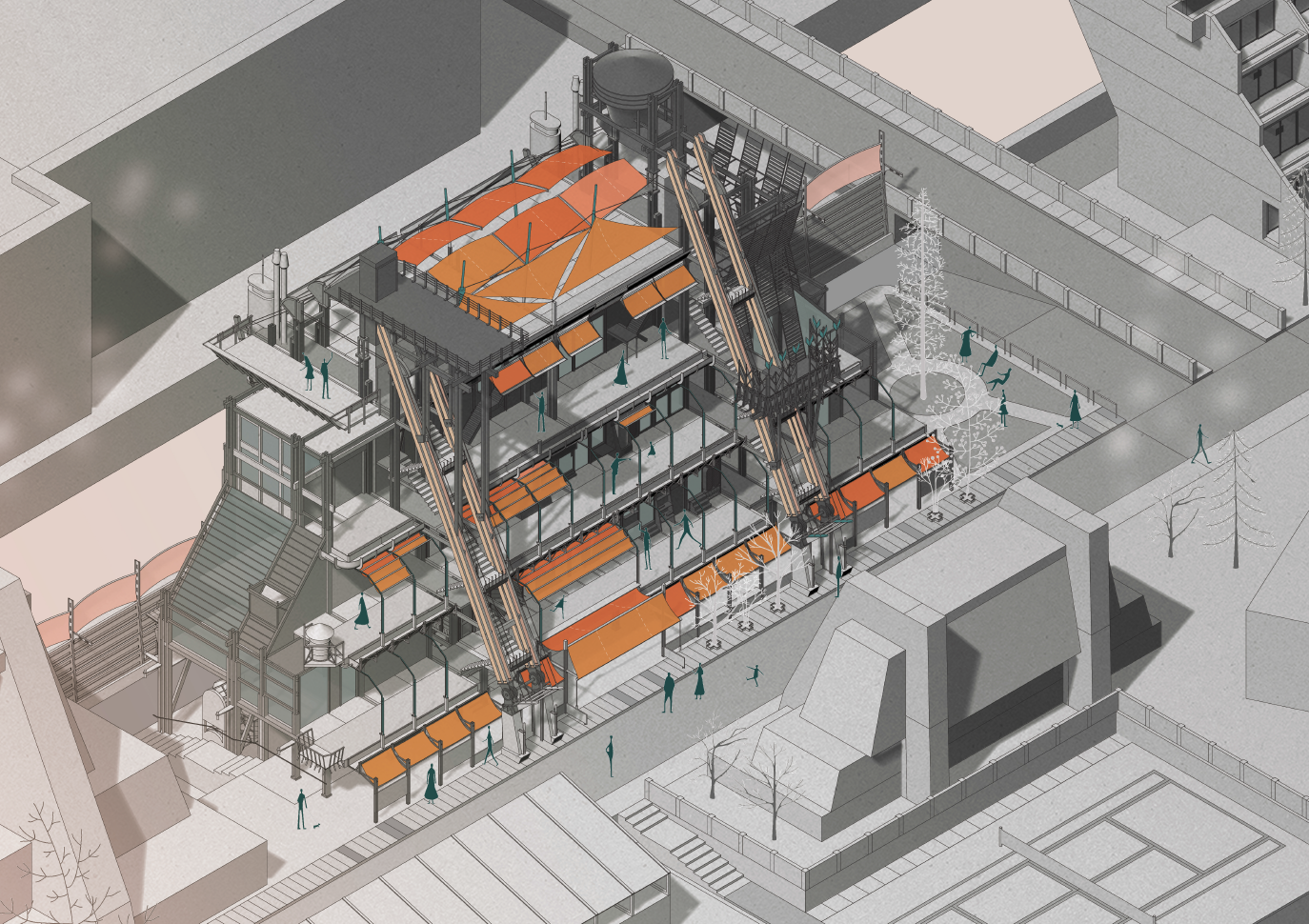

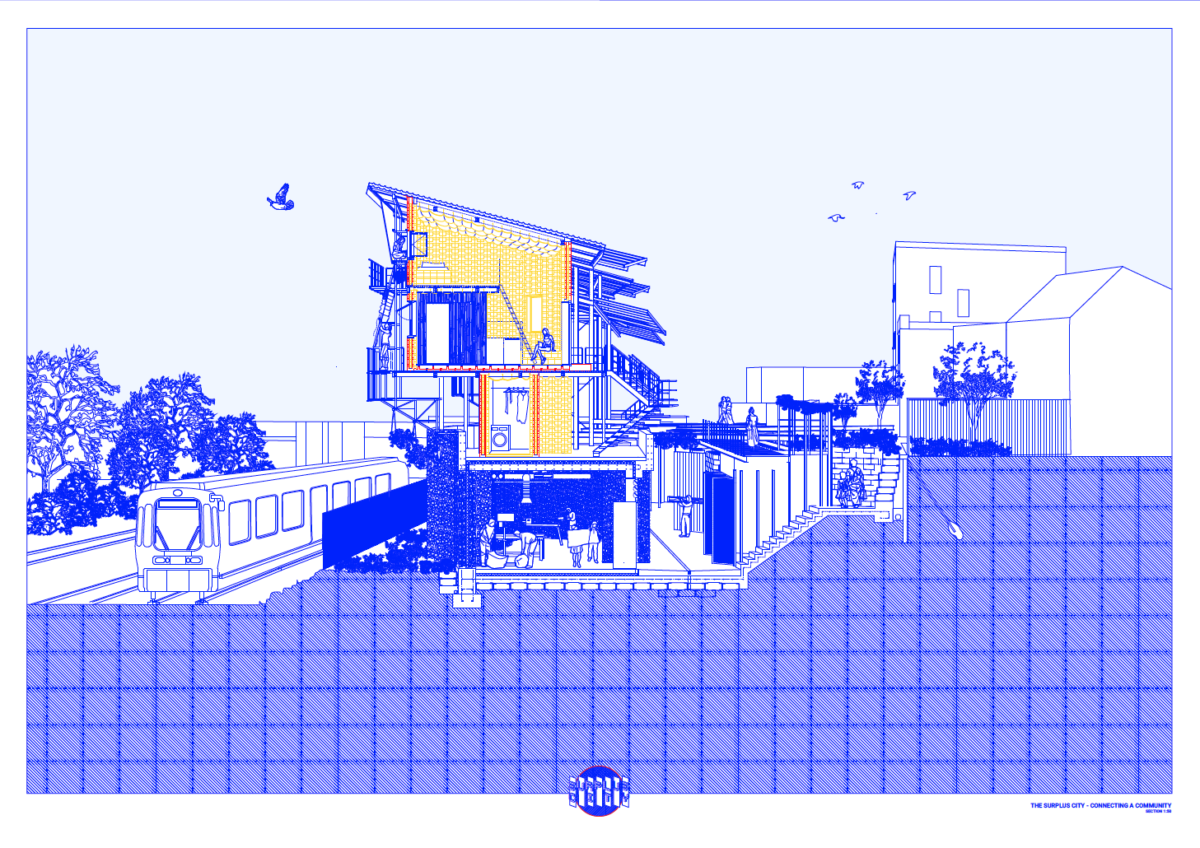

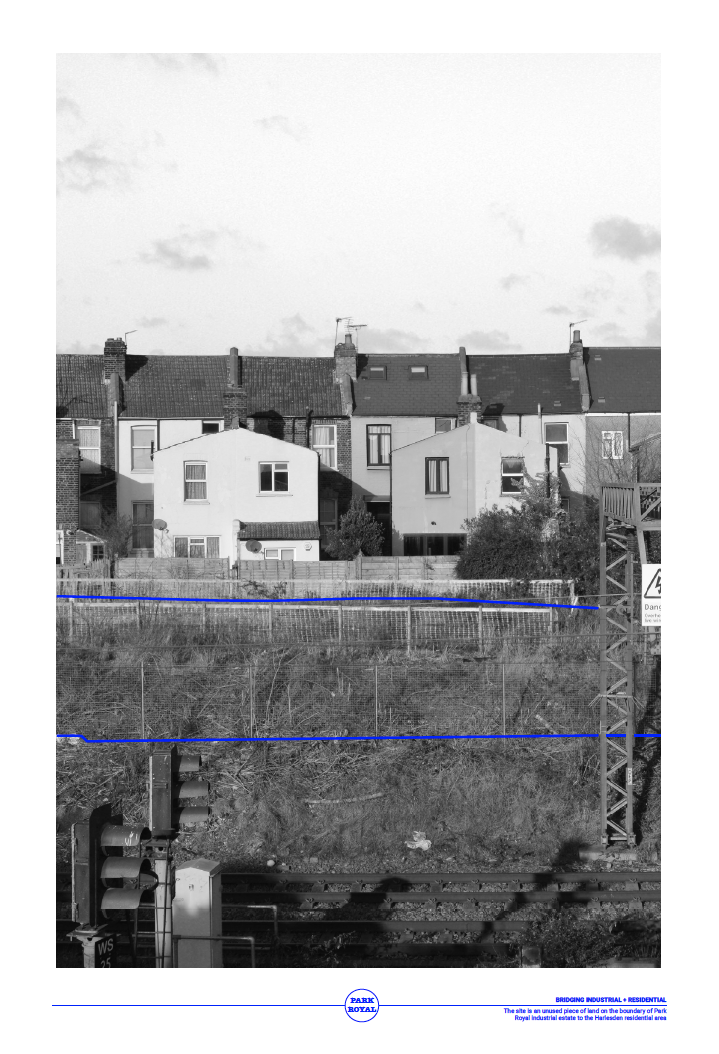

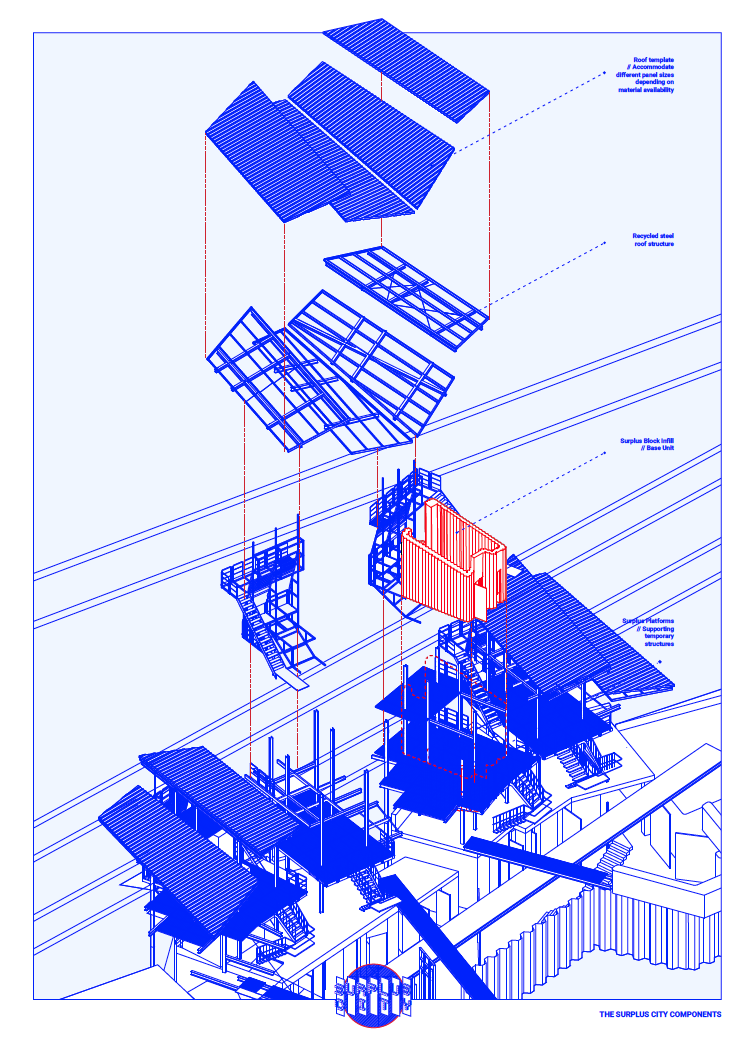

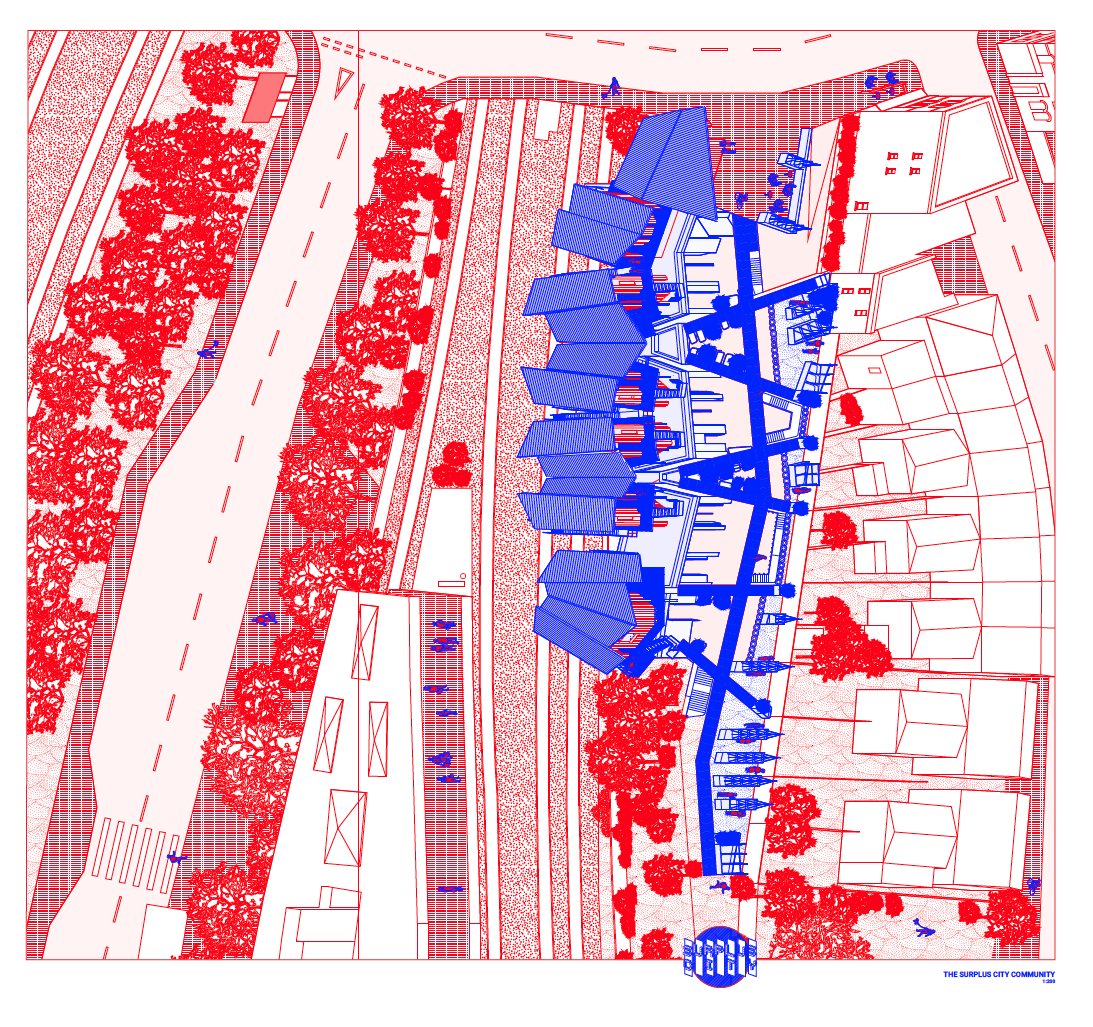

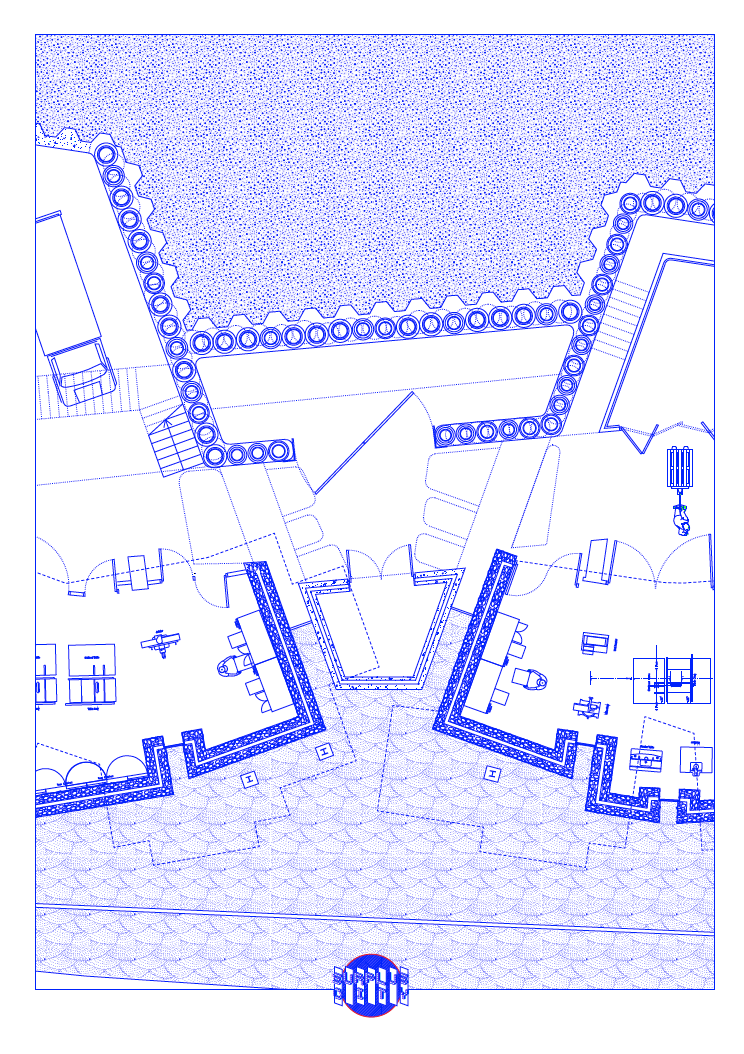

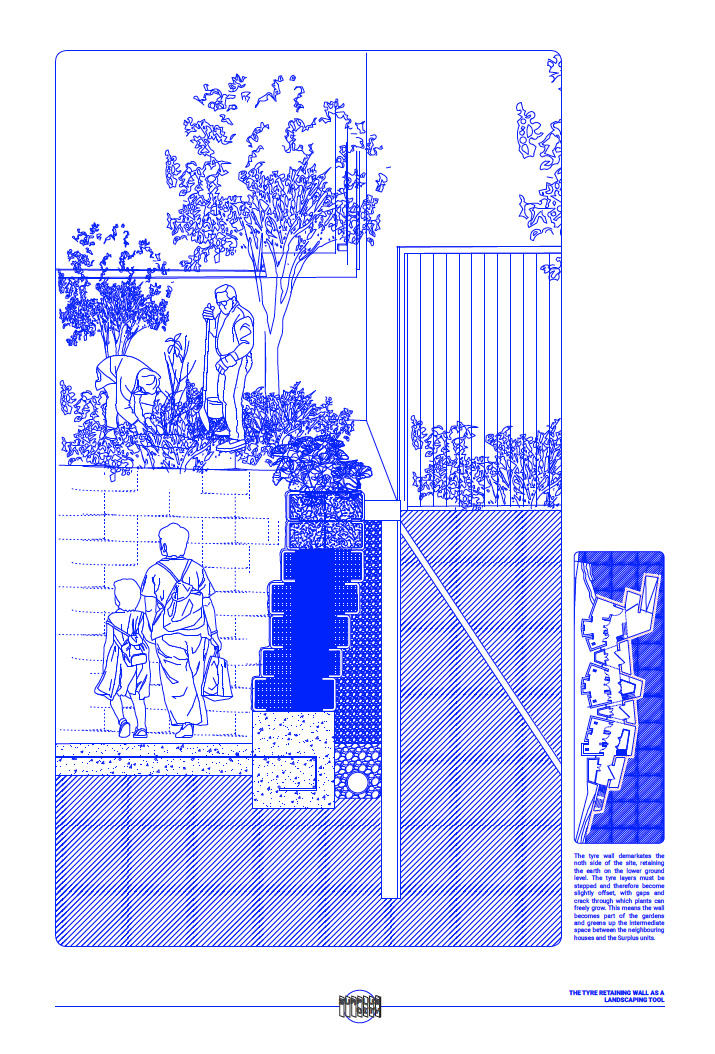

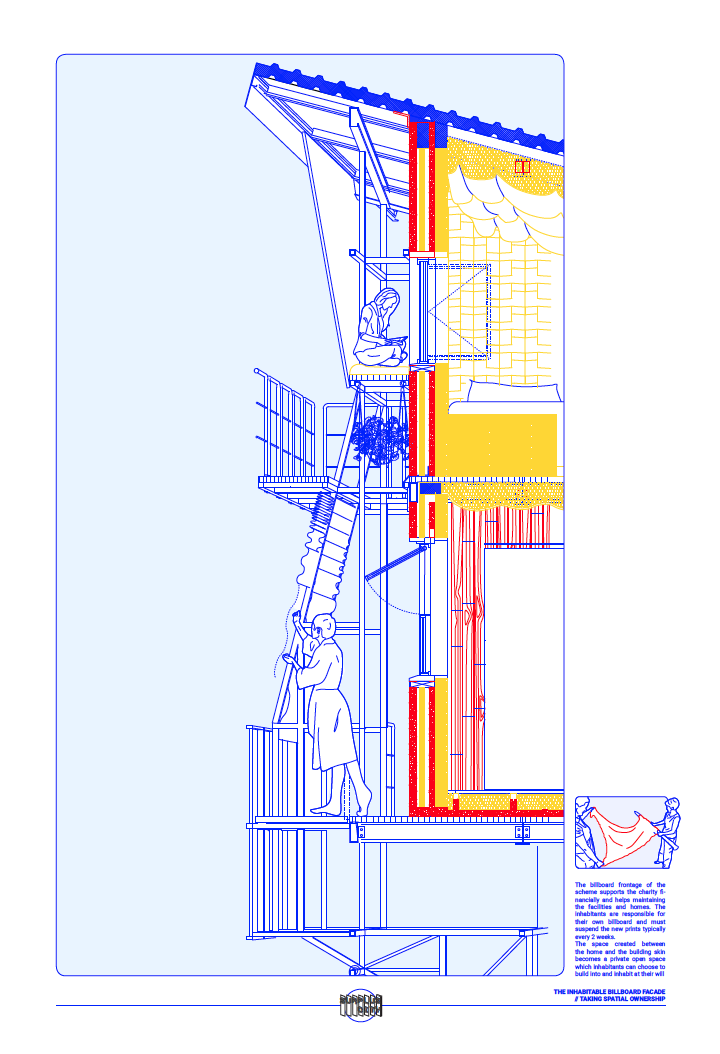

Park Royal Surplus City, London

Community Cathalyst Architecture

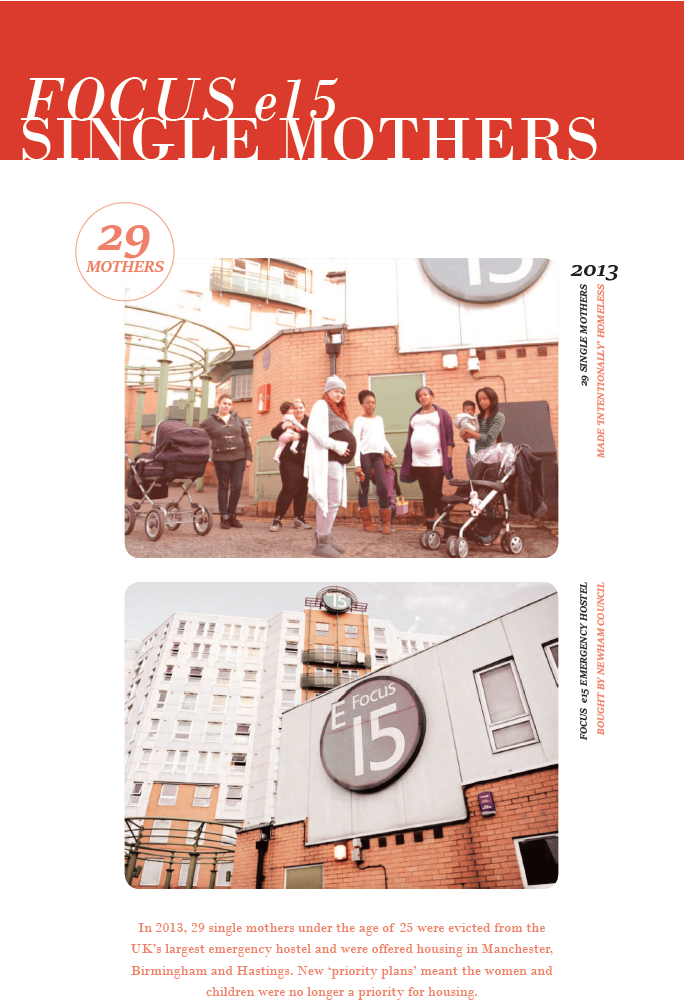

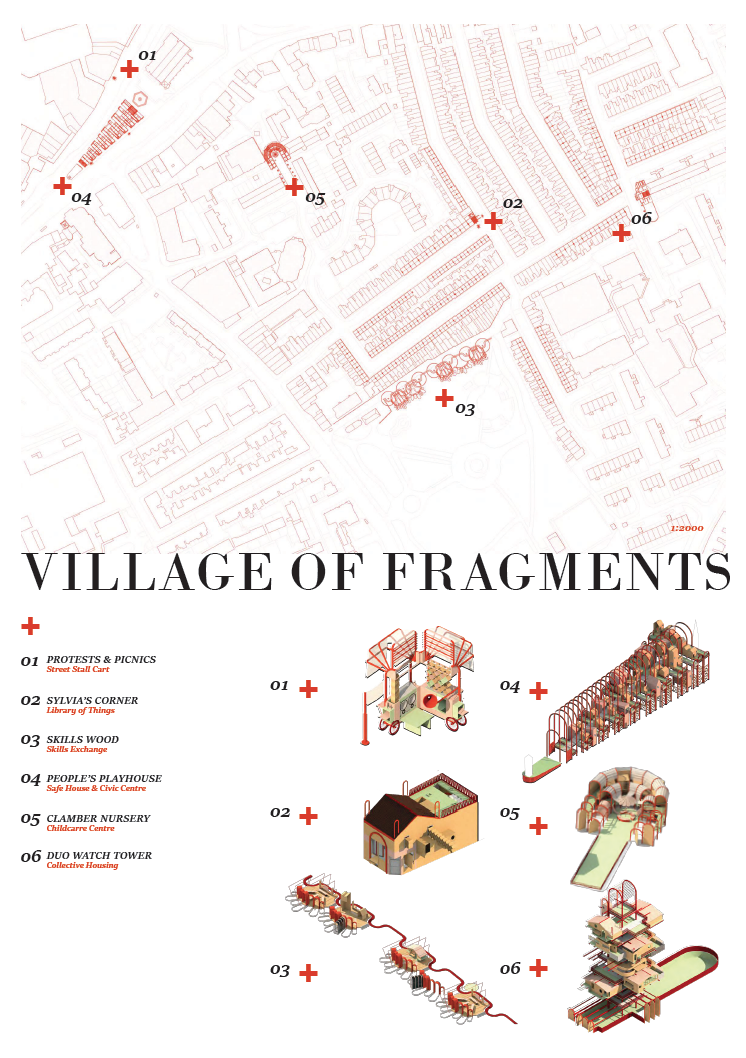

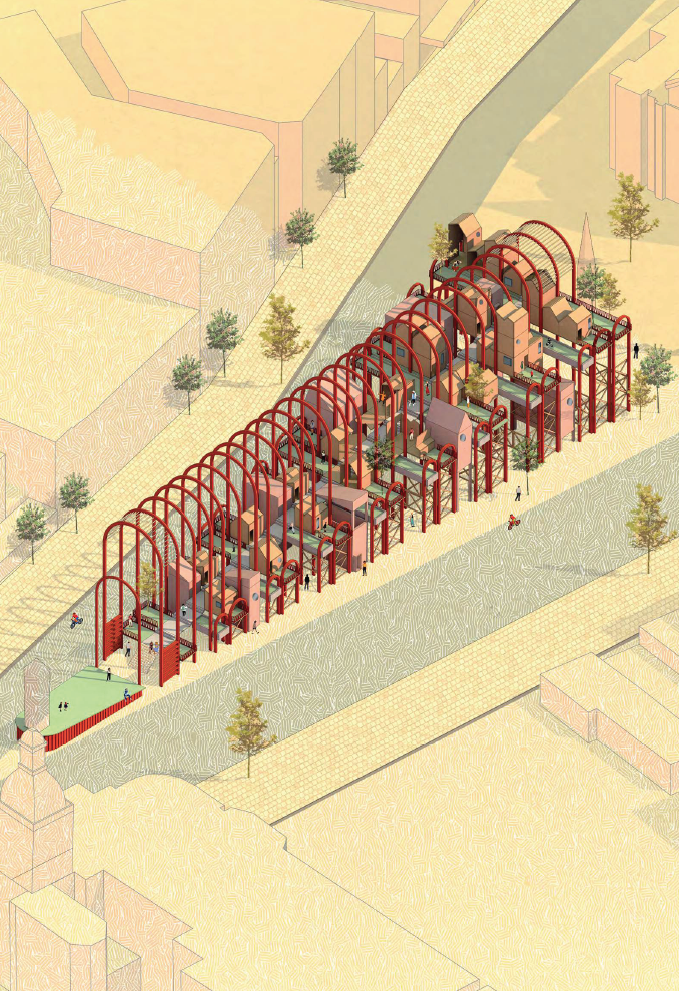

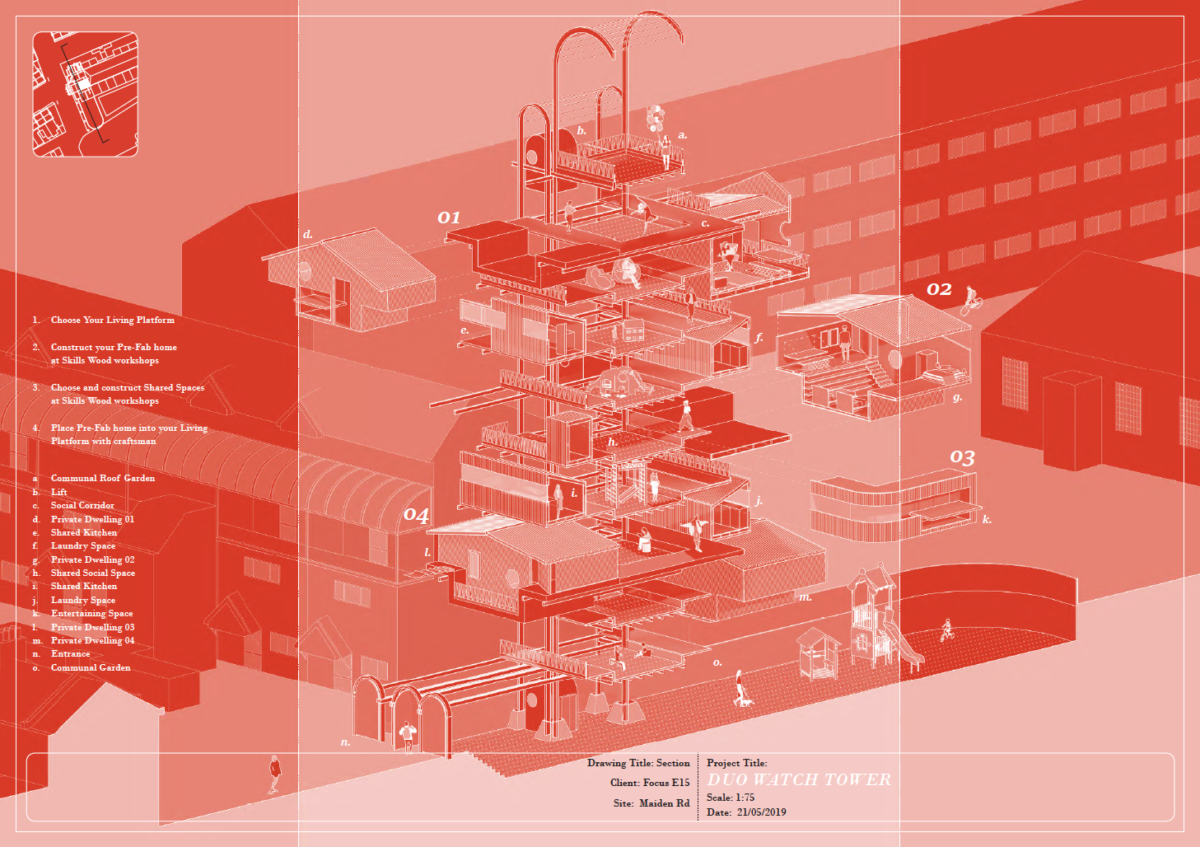

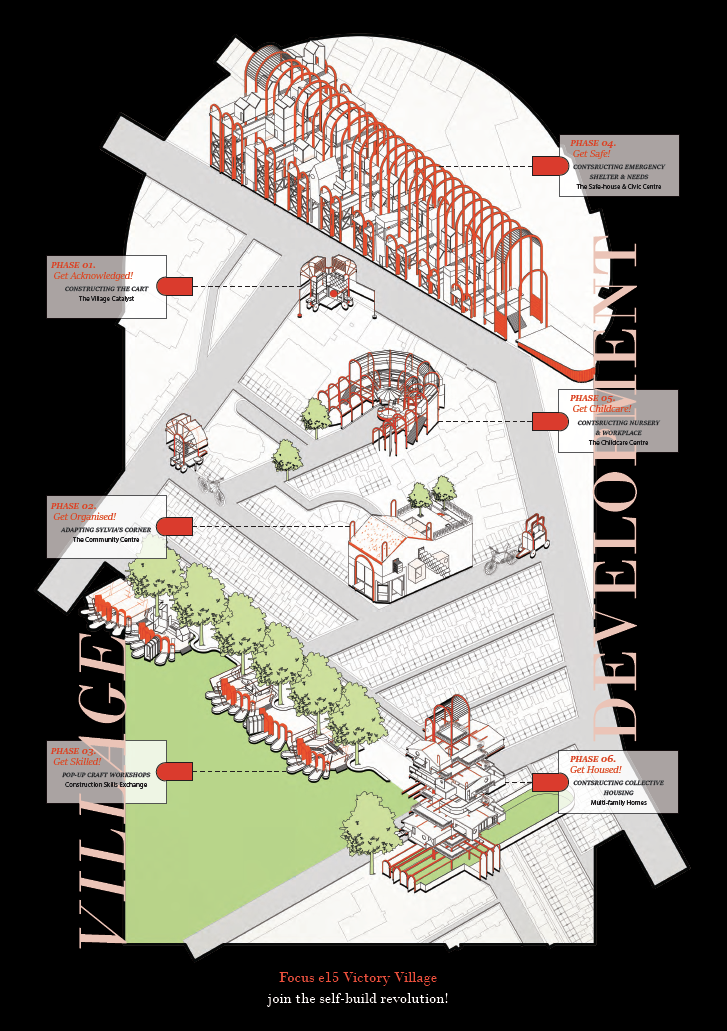

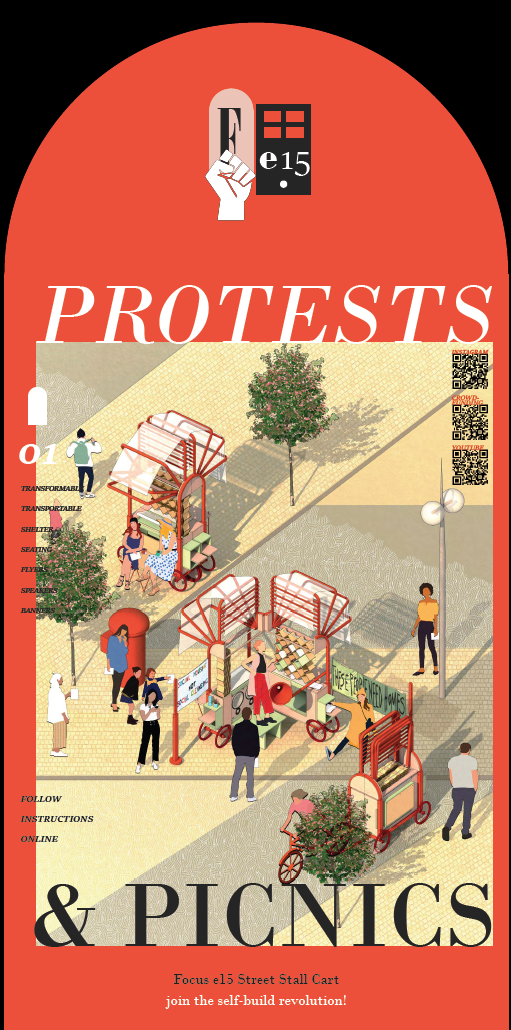

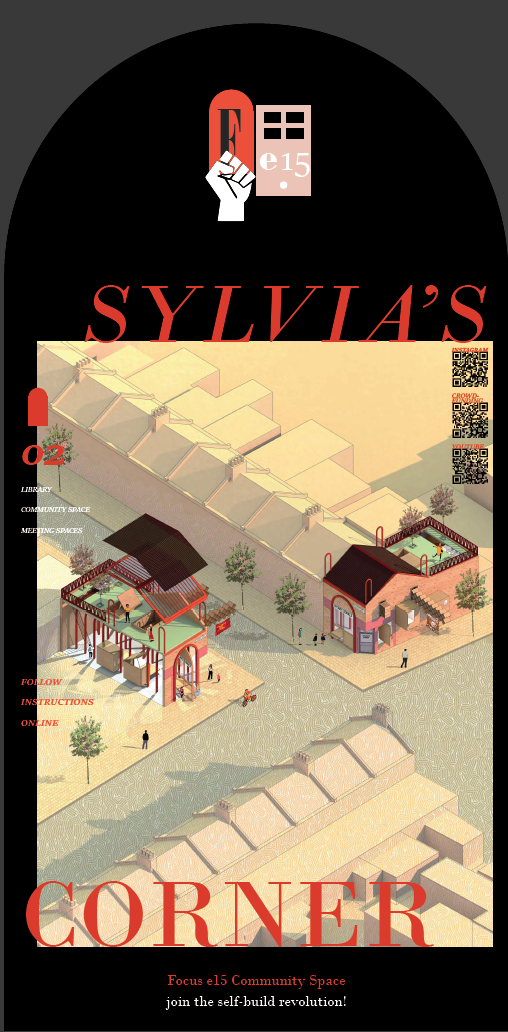

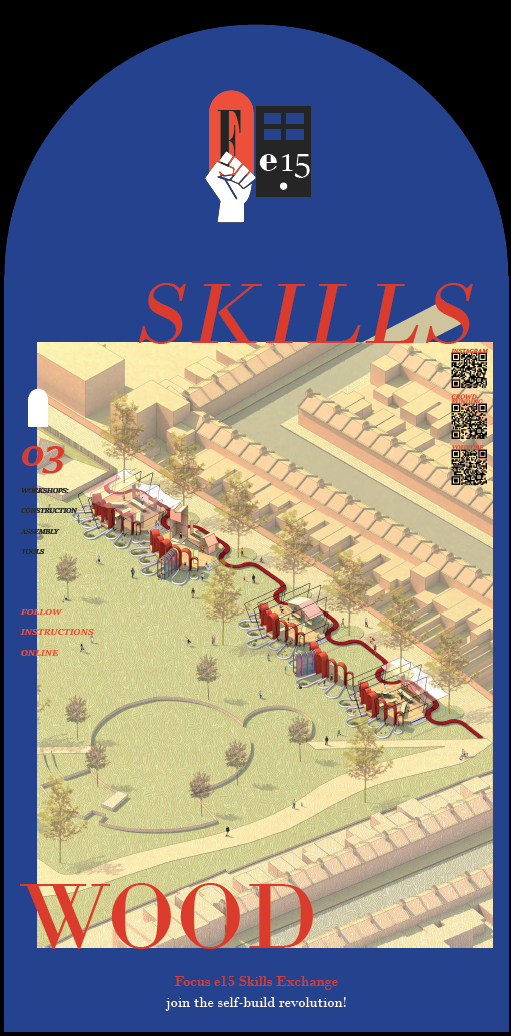

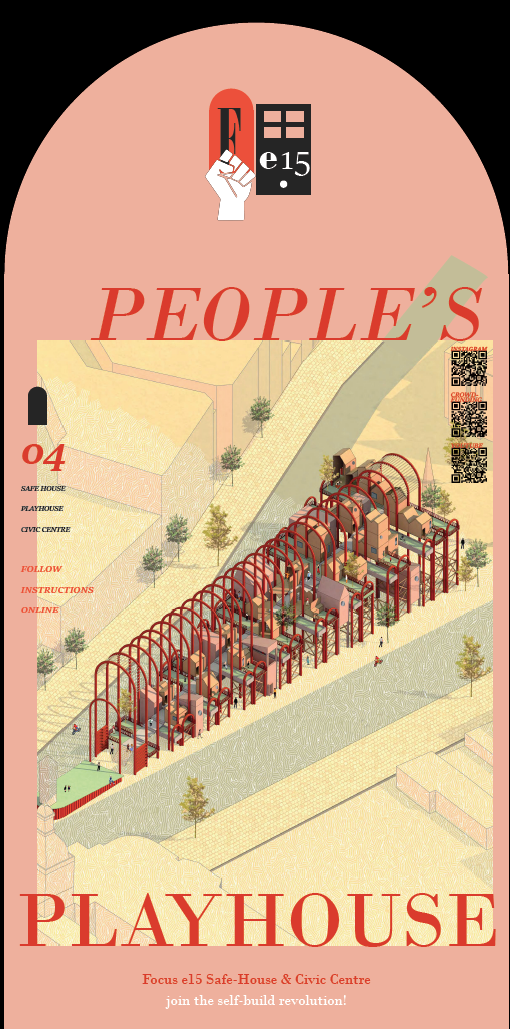

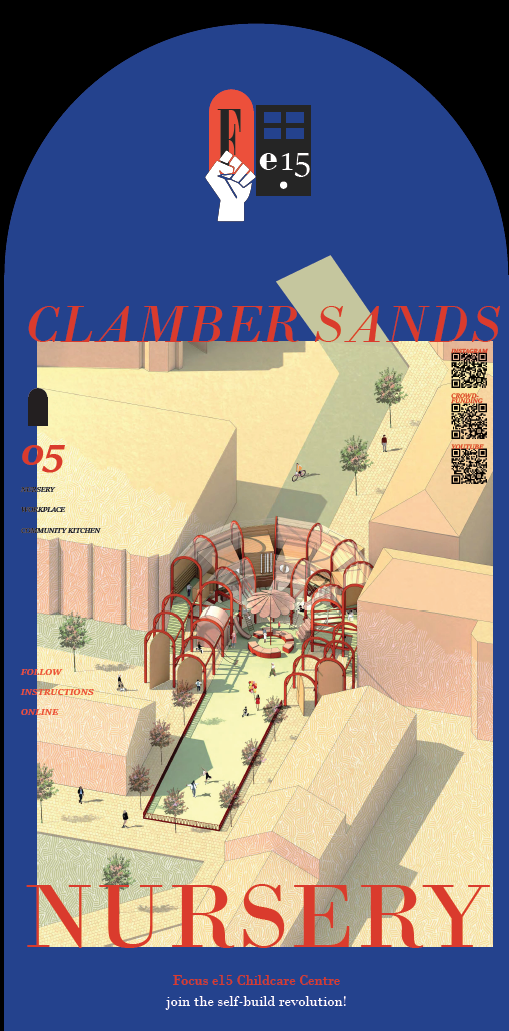

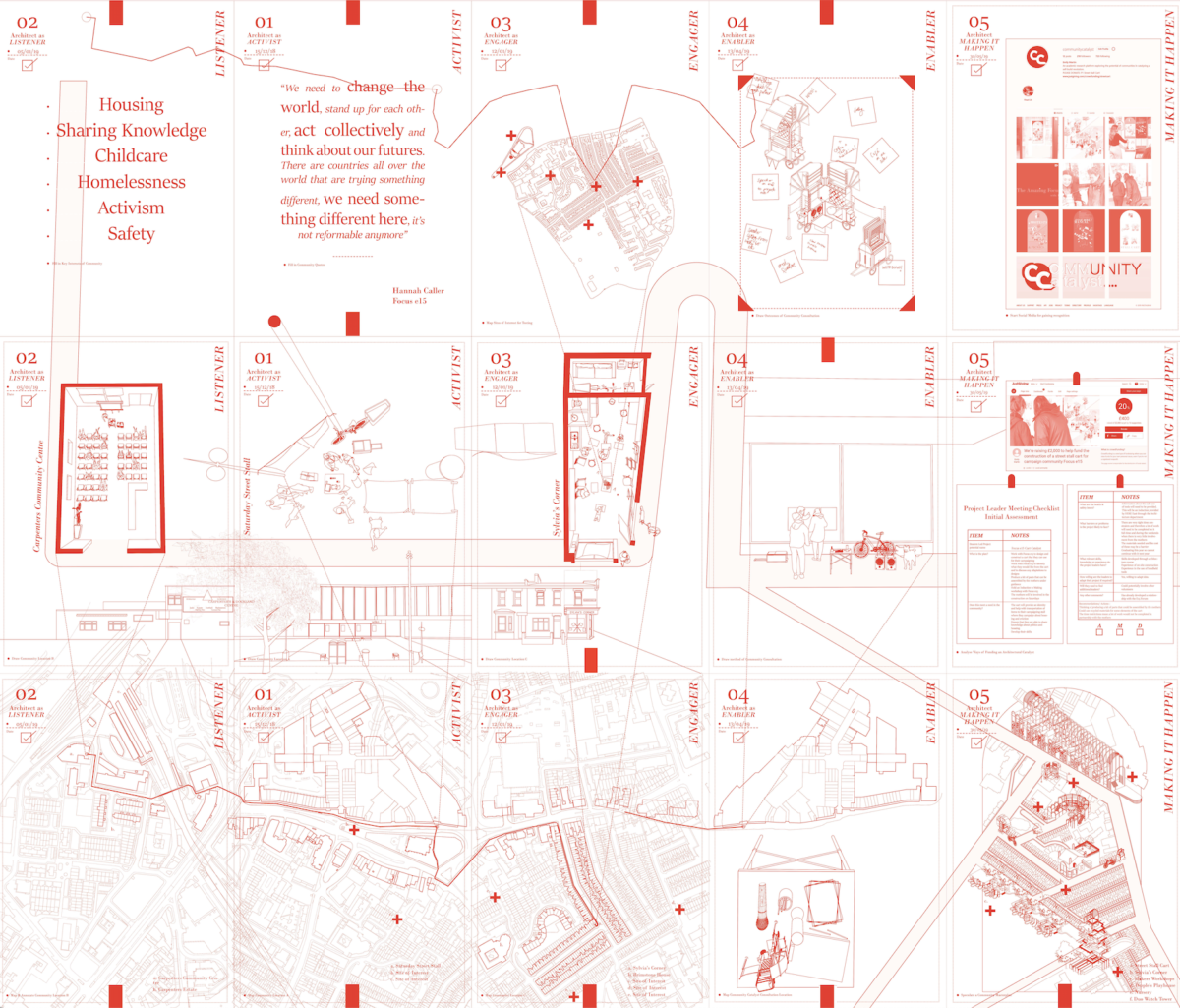

Negotiating the Future of Architectural Practice FOCUS e15 VICTORY VILLAGE

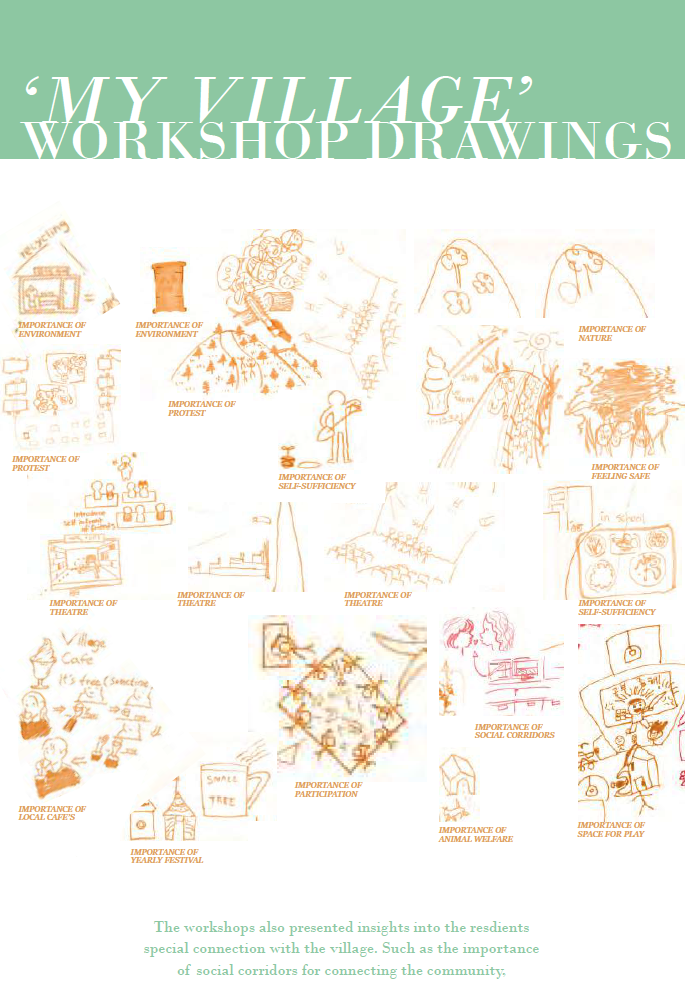

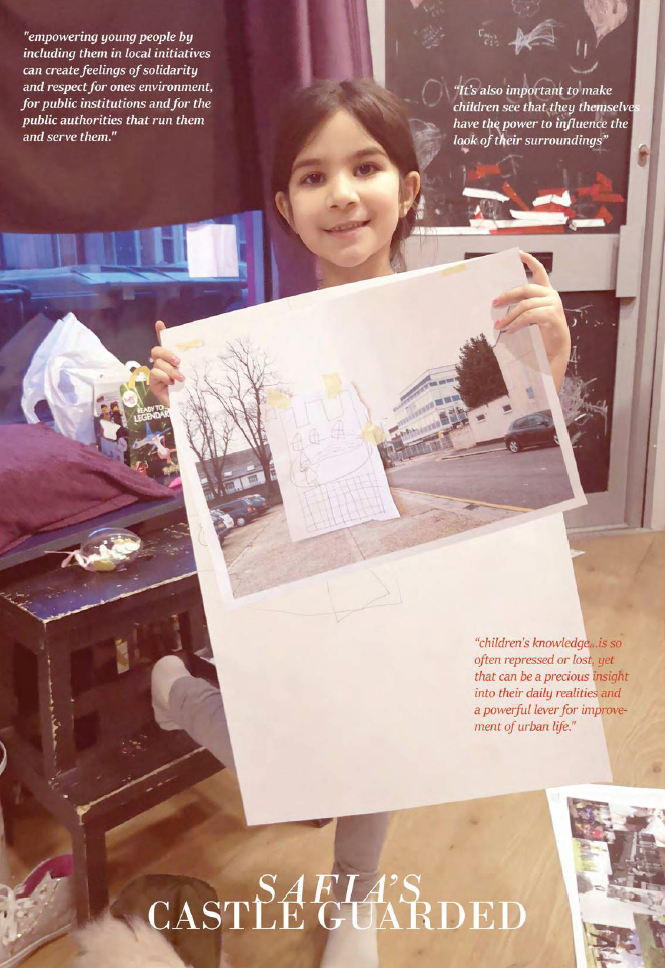

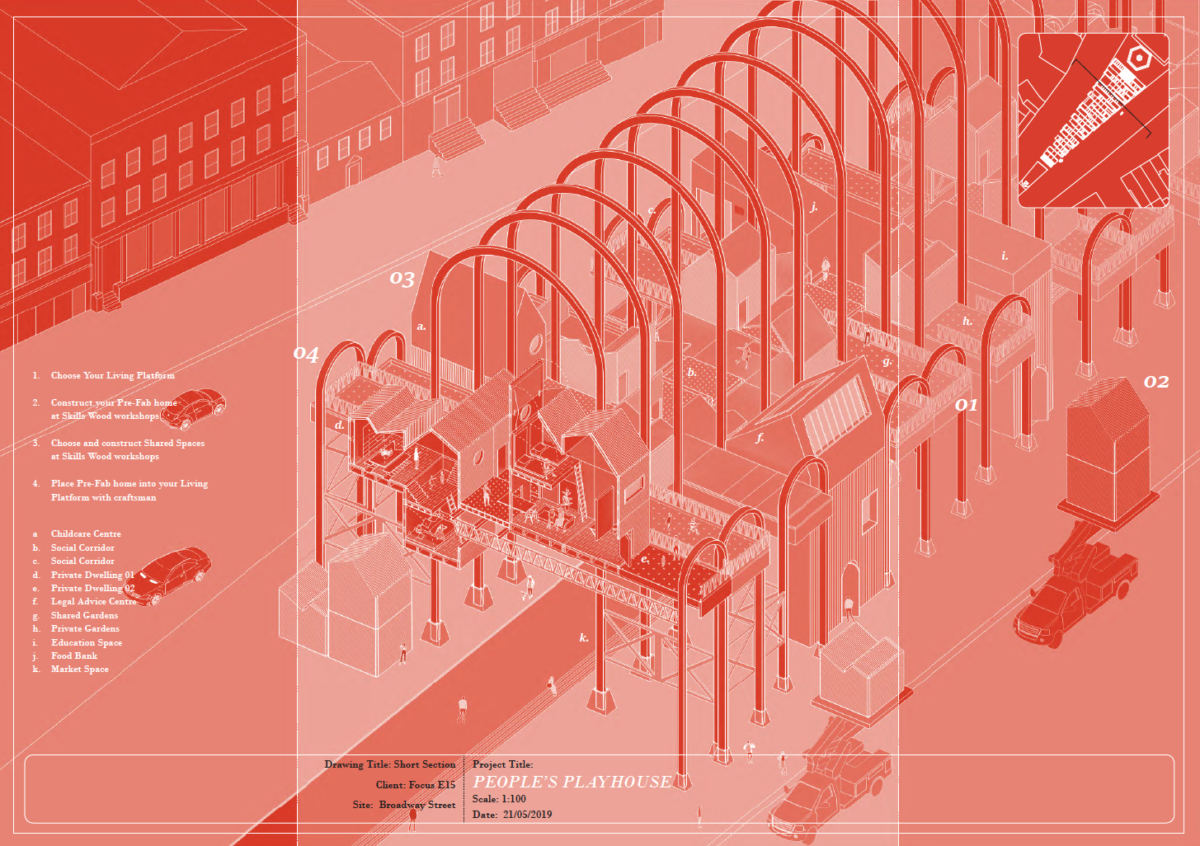

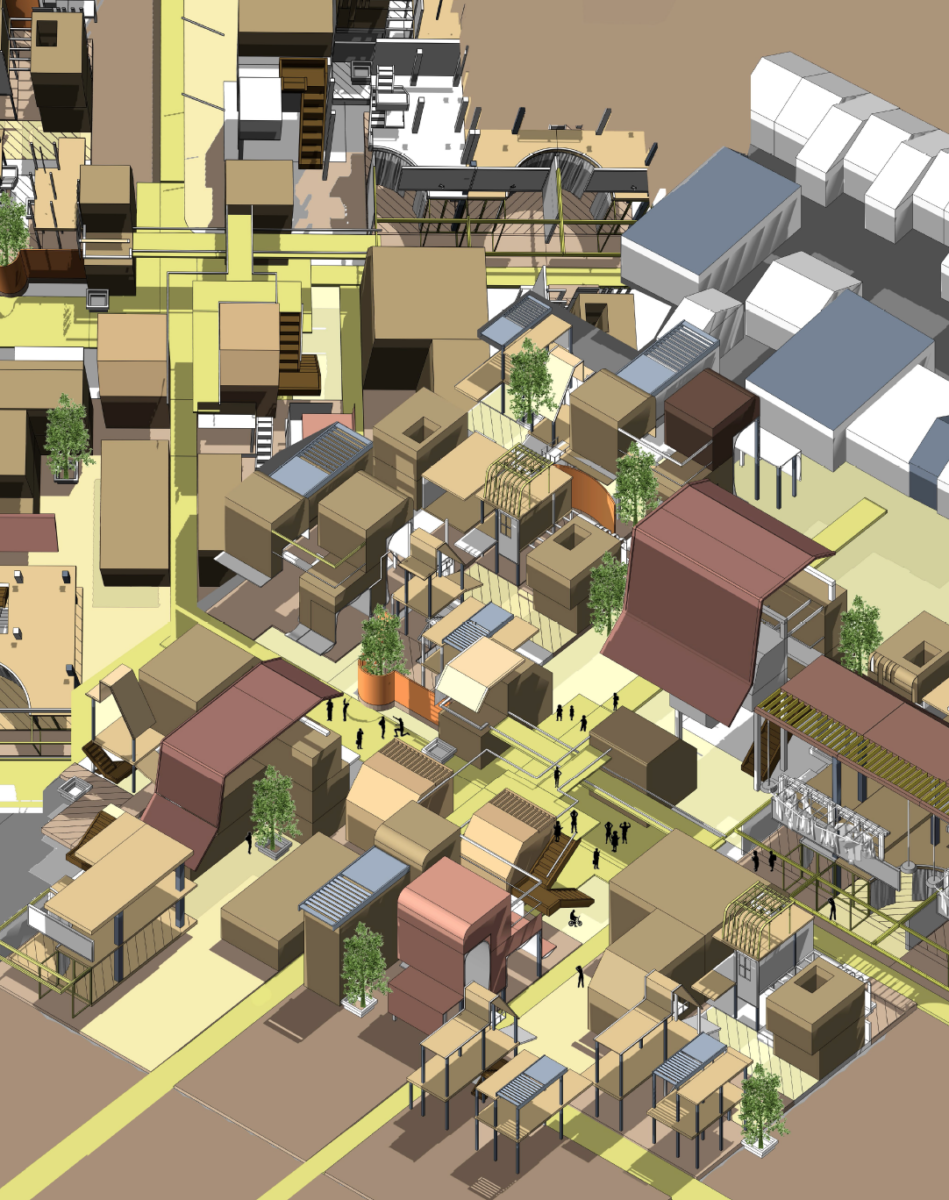

Community Catalyst is a project which negotiates the future of architec-tural practice through re-working the process into an opportunity for community driven development, catalysing and nurturing inclusive use and rights to the city. By developing a new participatory method as a manual of engagement, through direct involvement and collective action with local communities, the potential for such collaboration to transform and re-appropriate contemporary living opportunities is translated by developing an architectural campaign.

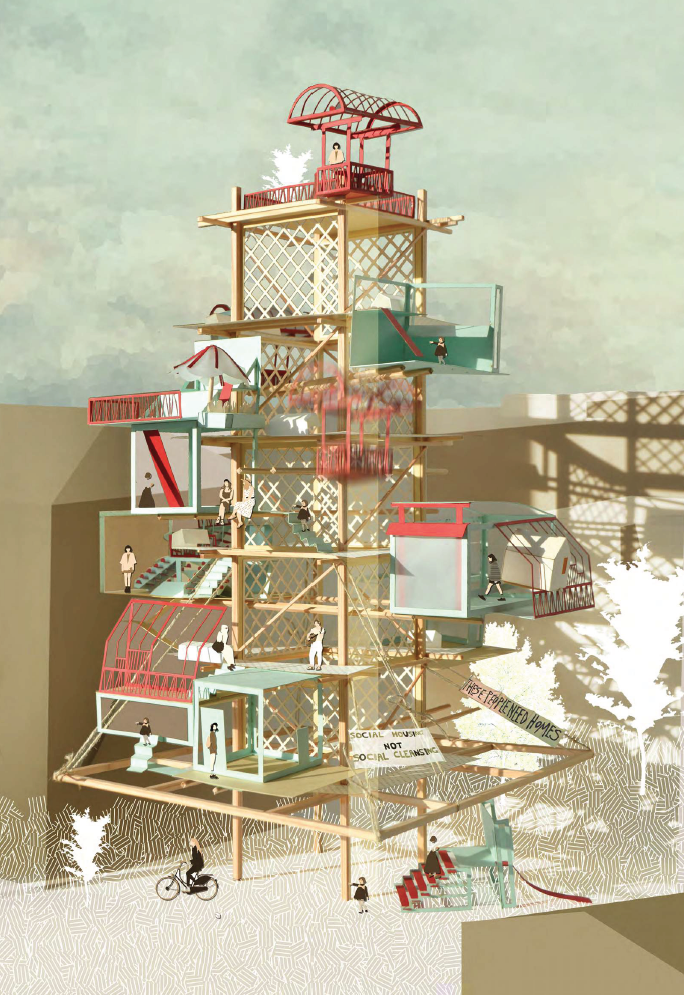

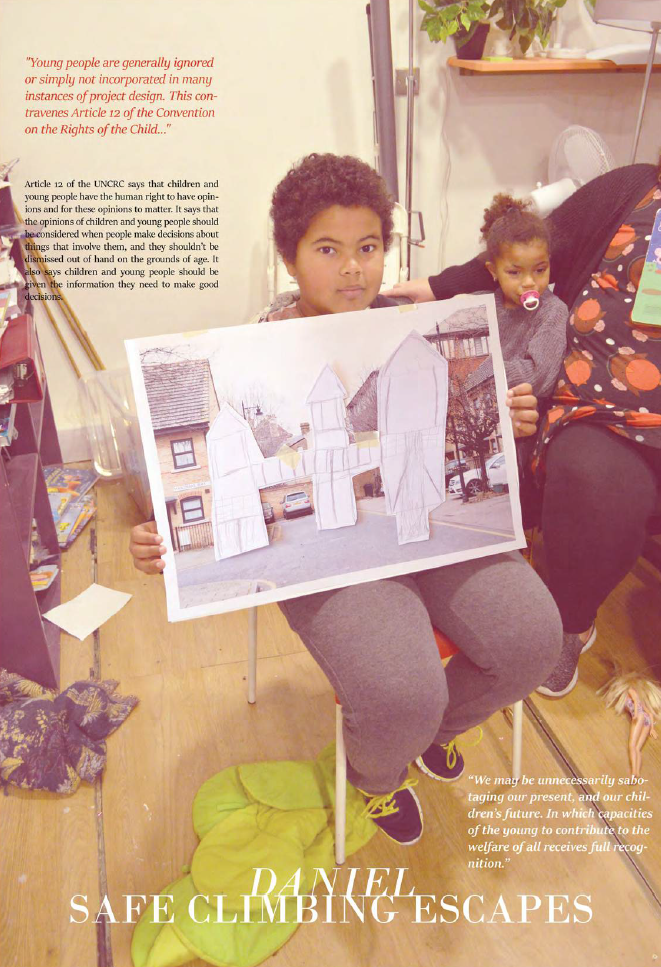

Through activating and enabling communities the ability to construct their own collective architecture, the process of empowering a com-munity through engagement is explored through the development of an architectural catalyst. Through such inquiry it is suggested that by constructing the catalyst with the community, the architect may enable the community’s construction of further architectures, thus suggesting the potential for catalysing collective urban villages.

The inquiry realises the importance of creating sustained relationships with communities as key to catalysing such architecture. Through building trust and common goals with campaign community Focus e15, through expanded practice, a commonality for enabling co-authorships of architecture, particularly housing, is developed, and, with this, Focus e15 Victory Village becomes anticipated.

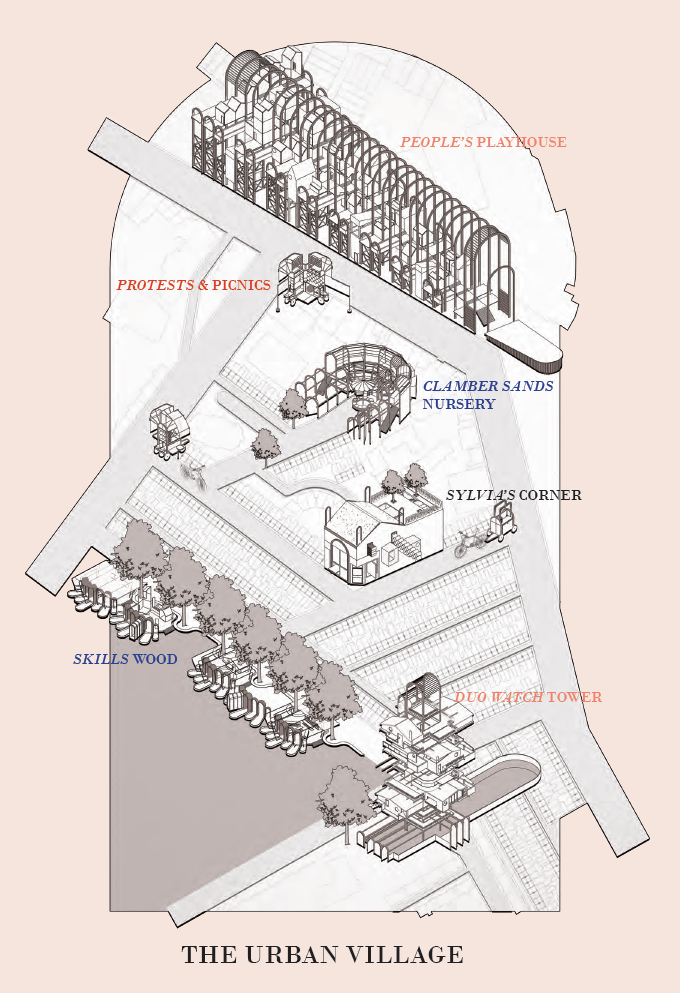

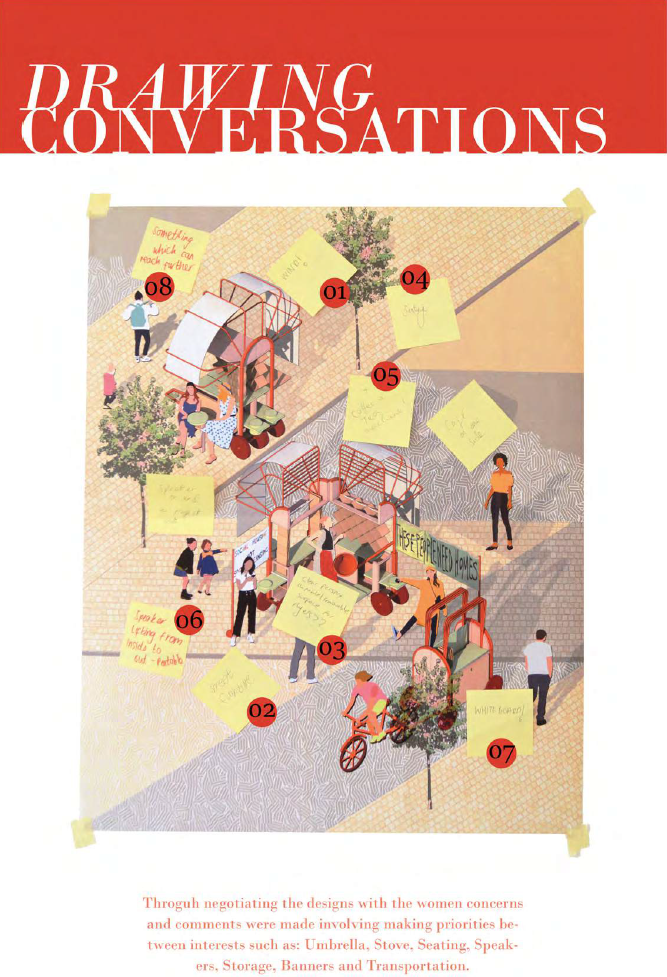

Through promoting, provoking and participating in grassroots activism, the project aims to catalyse and enable Focus e15 campaign to collectively construct their own urban village in Stratford. Through engaging new methods of participatory practice, such as through architect as activist, listener, engager and enabler, such roles for expanding architectural practice are deemed essential for constructing catalyst architecture.

Through such practice, users and people directly affected by designs are included as stakeholders and provided the knowledge and ability to understand and have impact on their projects. Such process suggests the importance of passive and active involvement by the architect to gather a true understanding of needs and interests of a community.

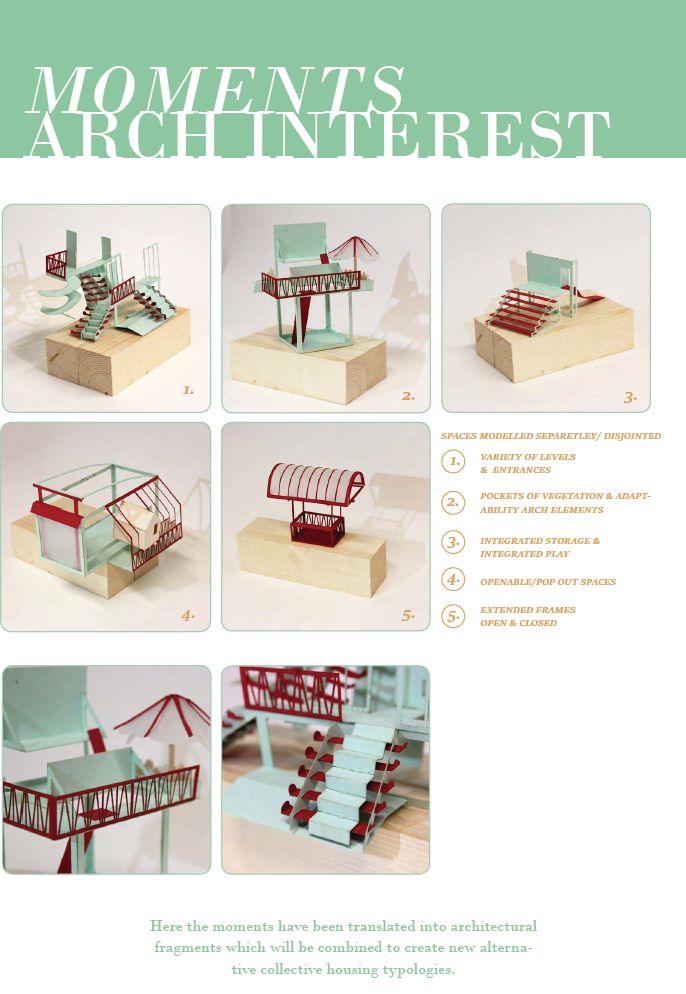

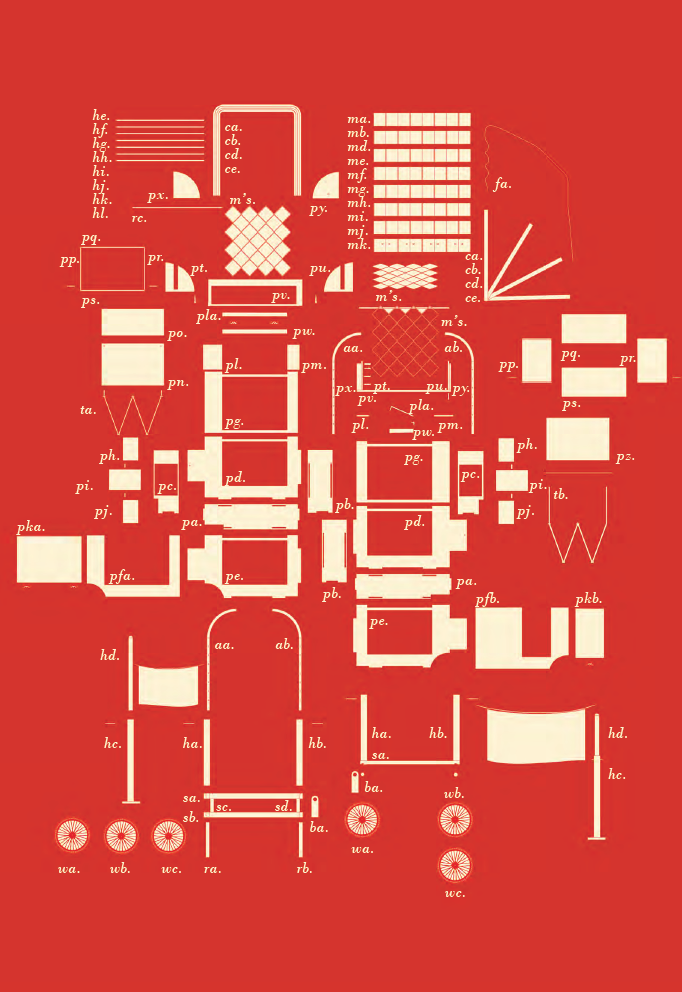

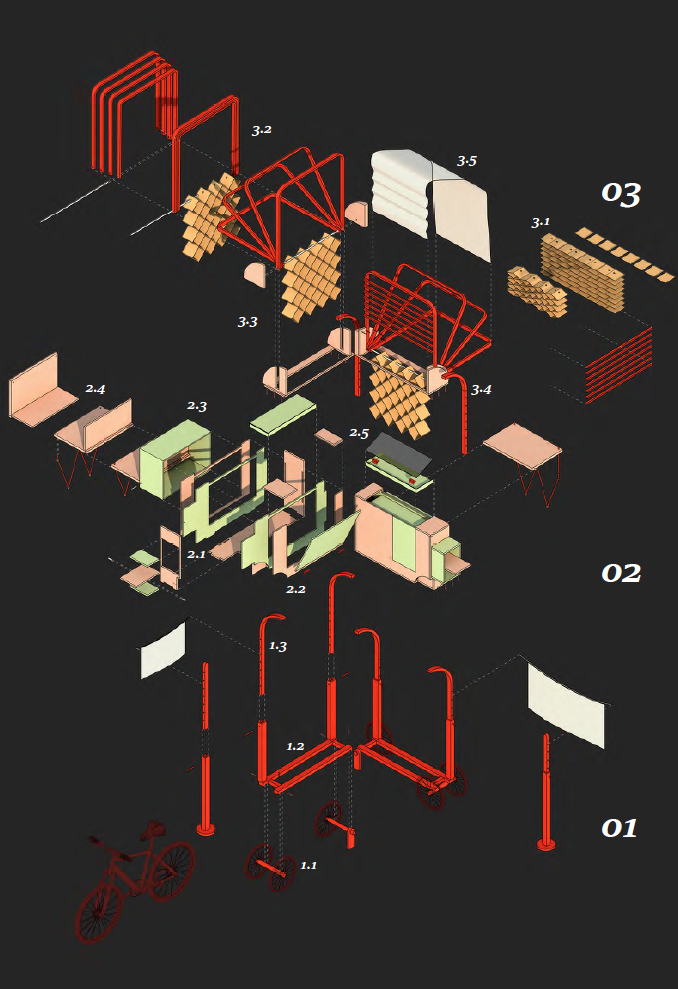

With this, the project promotes a series of stages designed as architec-tural fragments which eventually collectively combine and culminate in creating Focus e15 Victory Village. A village of fragments constructed from self-build systems for single mothers. Designed easy to assemble and arrange, the architecture enables the mothers to create their own collective homes specific to the needs of their families, empowering and liberating the community through architecture.