Author: admin

The French radiologist Dr. Jean Saidman invented the revolving sanatorium. Build 1930 in Aix-les-Baines in France the whole structure revollved to allow patients facing constant exposure to the sun. Thsi was an attempt to cure them of tuberculosis and rickets.

Sweet Water Organics, a company in Milwaukee, raises perch and grows leafy green vegetables in a former factory.

Urban Sweet Water Organics launched in Milwaukee in 2009 combining growing green vegetables with raising fish. The fish lives off the waste products off the plants and the plants grow on the fish waste.

THis circular system uses 90% less water compared to traditional fish farming while producing hundreds o kilograms of vegetables and fish in a closed system.

The destruction of our environment through intensive farming – both on land and in the water – has left vast areas of our environment stripped of biodiversity, oversaturated with fertilizers, ruined by pestizides.

Sweet Water Organics – Milwaukee

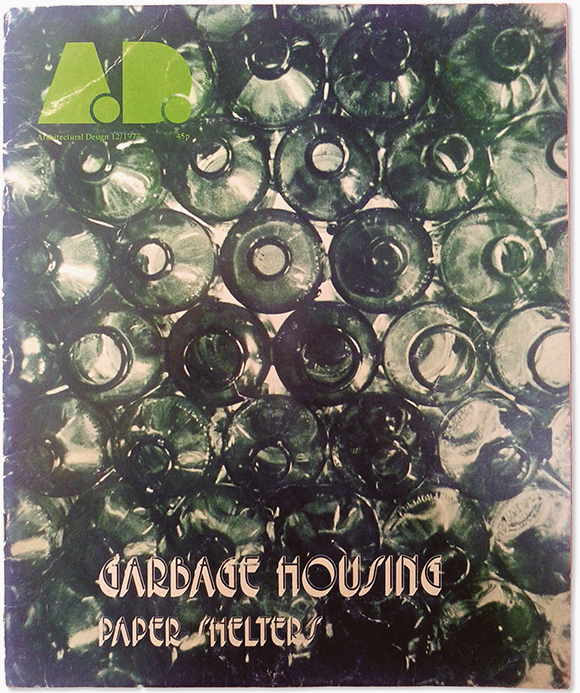

Recycling seems to have finally become mainstream – thanks god for that! But it hasn’t always been like that. The throwaway culture started a long time ago and it seems some visionaries have seen the writing on the wall long before the rest of us has caught up to this.

One of these visionaries has been Martin Pawley, a british architect who promoted his ideas for the garbage housing as early as 1975.

Nowadays we all talk about recycling, how we should avoid creating more and more waste to pollute our planet.

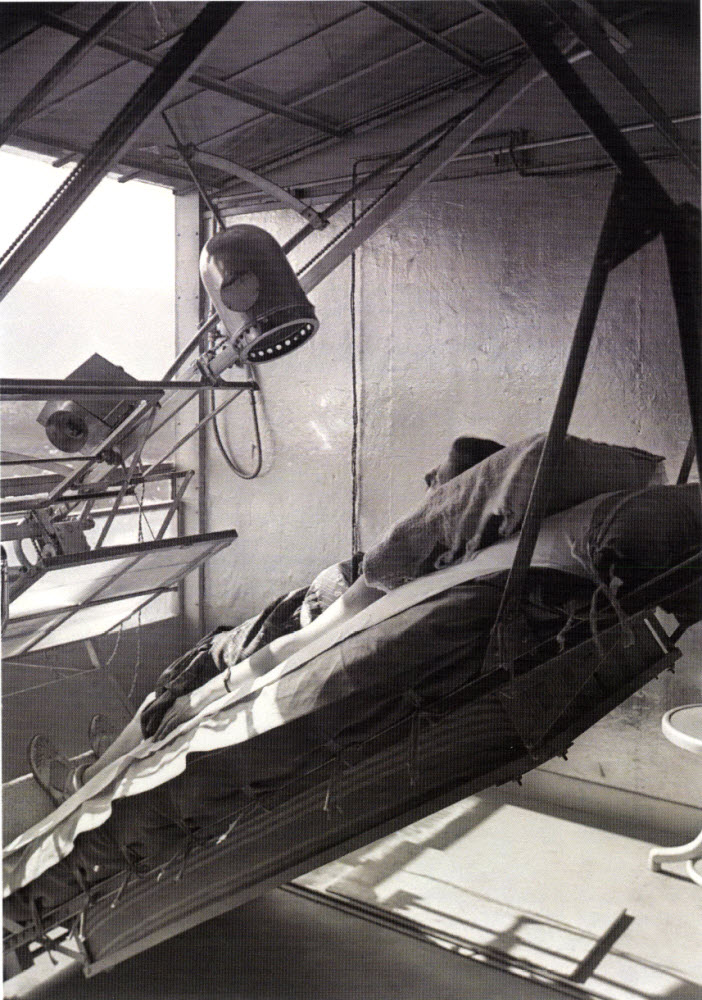

The designer Aino Aalto resting on a lounge chair on the solarium terrace of the Paimio Sanatorium in 1932. Photo taken by Alvar Aalto.

In the 1920-1930 a new movement in architecture emerged from Europe. Modernism promoted an architecture that was characterised by its clean lines and white walls. Functional spaces that were pure and free of any decoration or ornamentation associated with historical architecture.

But on closer inspection this new movement was not about style, about dismissing the architecture of the past on aestetic or purely formal grounds. It has much deeper roots in the desire to eradicate tuberculosis, a disease that, at the time, didn’t have a medical cure.

Robert Koch discovered the tuberculosis bacillus in 1882 but until 1949 there wasn’t an effective medical treatment for this disease. It had been understood that the disease spread and was dormant over long periods of time, hidden the dust of the houses with a poor ventilation aggravating the situation. In 1900 tuberculosis was responsible for 25 percent of all deaths in New York.

Modernism must be seen as a reaction to this crisis. At the time the only real cure for the disease was what was called the Freiluftkur, where a person was treated with plenty of fresh air, lots of sunlight, and nutritious food. The standard ‘cure’ for TB was primarily a change of the environmental conditions. Very soon architects responded to the challenge by devising an architecture that was dominated by clean lines (that were easy to be cleaned), surfaces free of ornamentation (trapping dust and spreading the disease). Buildings were elevated off the ground (to allow air to circulate and to remove the inhabitant from the damp ground), walls were penetrated with large windows (allowing in sunlight and fresh air). These building were not machines for living, they were machines for healing.

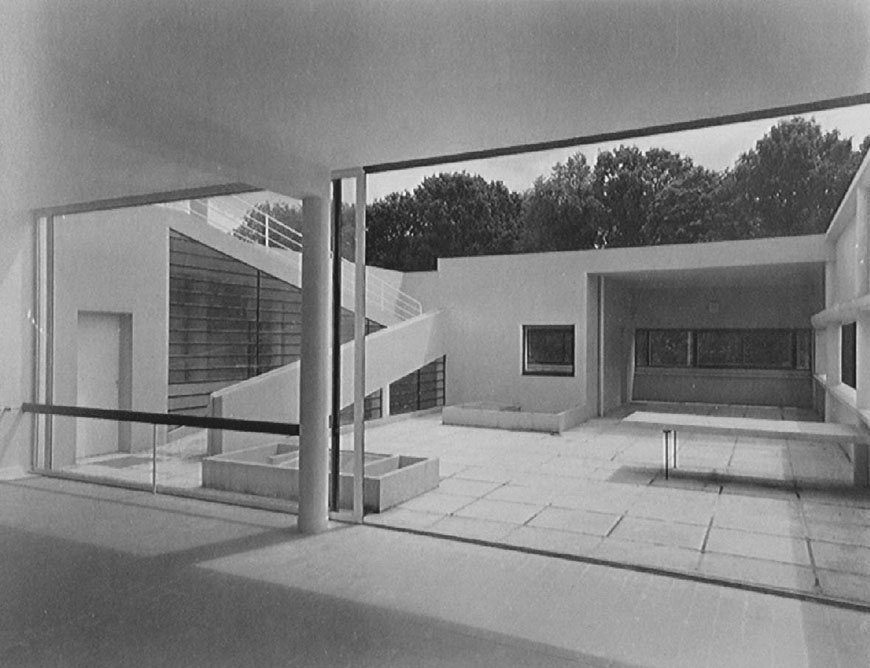

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoy, Paris, 1929

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoy, Paris, 1929 Open airy spaces, light flooding into the living spaces.

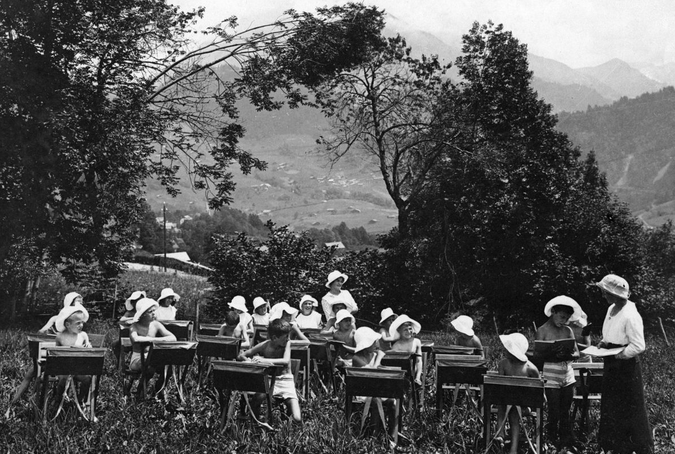

Children being taught in the open air, ca. 1920

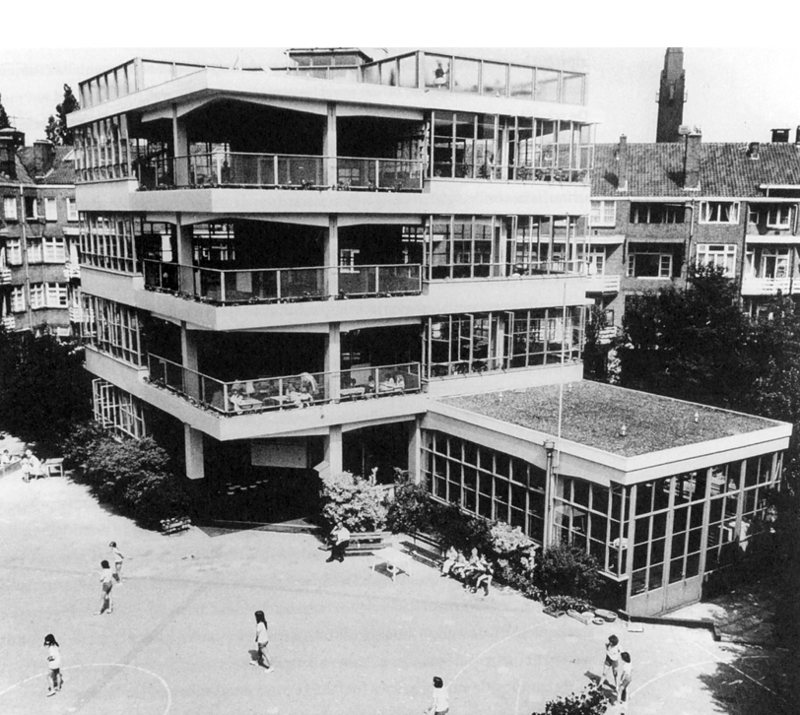

Jan Duiker, Open Air School, Amsterdam, 1927

x

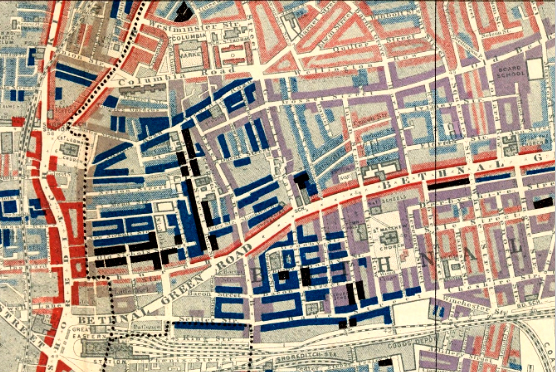

Charles Booth’s Descriptive Map of London Poverty 1889 showing The Old Nichol area, later transformed into the Boundary Estate. Areas in black are indicating ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi criminal.’

Old Nicol Road Slums / Boundary Estate

At the height of the British Empire, with Queen Victoria ruling over large parts of the world, unimaginable riches flowed back to England from the overseas colonies. The new global trade routes made English industrialists immensely wealthy. Like today these riches were not spread equally across the population and most parts of London of the late 19th century was a dark place to live in. With people moving into the big cities looking for a better life, resulting in poverty and misery – this created huge overcrowded slums.

At the time hugh areas of land could only be leased for a maximum of 21 years. This mean landlords had no interest to create building that would last. But even this was too much for some peopel who woudln’t even be able to rent a bed for a night – being forced to get a space in in a room with robe beds – ropes to lean over and rest for the night.

‘Rope beds’ were a cheap but misreable way to spend the night in a doss house.

While some of the luck inhabitants were able to afford a space in a sleeping coffin, the ‘Four Penny Coffins’.

‘Four penny coffins’ were a relative luxury compared to the alternatives.

With nearly 6000 inhabitants the area once called Old Nichol was one of the worst slums of the East End in the late 19th century. Immortalised in the novel ‘A Child of the Jago’ by Arthur Morrison the area was highlighted on the Charles Booth’s poverty map is inhabited by the “lowest class, loafers, criminals and semi-criminals”.

The local reverent, Osborne Jay initiated the rebuilding of the slum which created the Boundary Estate, one of the world’s first council estates. The new buildings were influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and were built to a high standard. Housing over 6000 residents each flat was designed to maximise good light and air for the residents. Sadly, only 12 of the original slum residents moved into the flats, the others moving on to new cheaper areas in Bethnal Green or Dalston, taking the overcrowding with them.

The crisis of the clums led to the invention of a new housing typology, the council house.

Grim Realities of Life in the Slums

.

PG13 2020/2021

Being RADICAL – a platform for inspiring resistance and creativity

Unit PG13 – the Bartlett Living Laboratory is continuing to explore how we live, how we inhabit spaces and our cities; our students are empowering communities and inventing new typologies of living.

The most powerful architectures have been created out of a crisis, a rebellion, or a clear break with the past. The strongest pieces of architecture can be traced back to a radical new (creative) vision. This pattern can be traced all across the architectural history and at times of great uncertainty these radical ideas to emerge and flourish. What is needed is a shift in how we operate, a reconsideration of the basic principles of how we live, how we treat each other and our planet; what is needed is US being RADICAL.

Our work will form part of the Seoul Biennale 2021 and we are planning to host a workshop at the Venice Biennale in 2021.

Sabine Storp + Patrick Weber

The Bartlett Living Laboratory

London – Seoul Biennale – Venice Biennale

Unit PG13 is interested in how we inhabit our cities. The places we live in, socialise, engage with others, building a community are immensely important for the functioning in our post-Covid 19 world.

At times of great uncertainty, we strive to find a way out of the misery by projecting our dreams onto a better place – our own personal Utopia. Architects dream, they speculate on what ‘could be’ real, they dream of spatial manifestations of sometimes real-life problems. Most work produced is speculative, and although some are rooted in real-life situations it is not real, it doesn’t have a client, it will not be built. Yet these speculations, these speculative architectures are incredibly important to bring about change, to test out new innovative ideas.

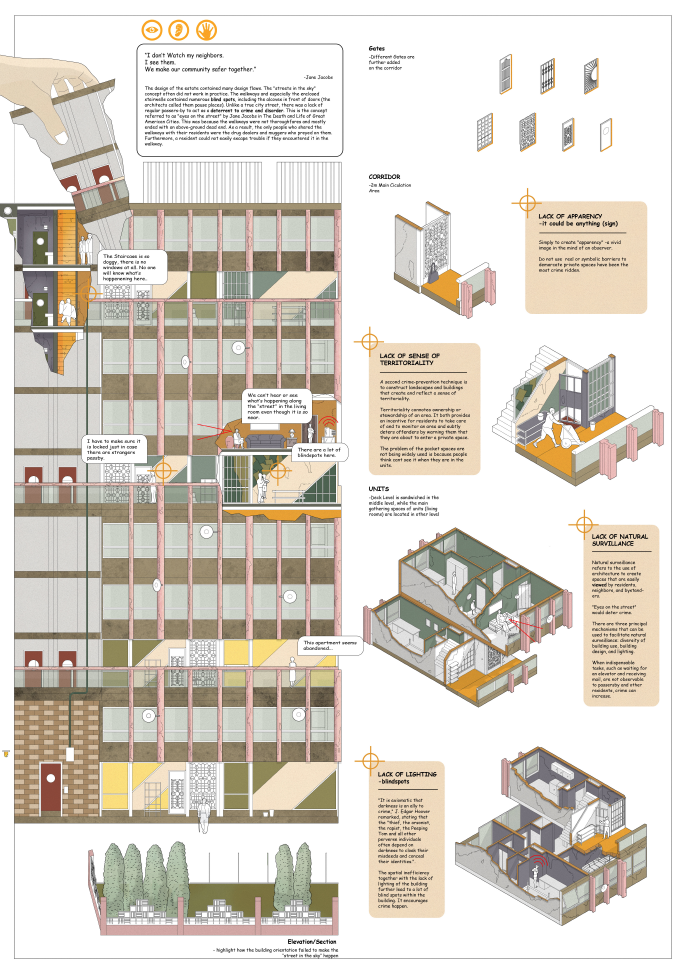

As an architect, you (usually) strive of building a better world. This spirit created some iconic housing developments on the 20th century in London– Alexandra Road and the Dunboyne Estate by Neave Brown, Robin Hood Gardens by the Alison and Peter Smithson, Trellick Tower by Erno Goldfinger to name a few. Sadly, other attempts to solve problems with a building have failed and created far bigger problems than the issues they were actually attempting to address. Modernism was seen as a brave new world for a modern forward-looking society. For many these utopian ideas have turned into dystopian nightmares of the inner-city housing estate. Yet some examples stood the test of time, they developed into living thriving communities.

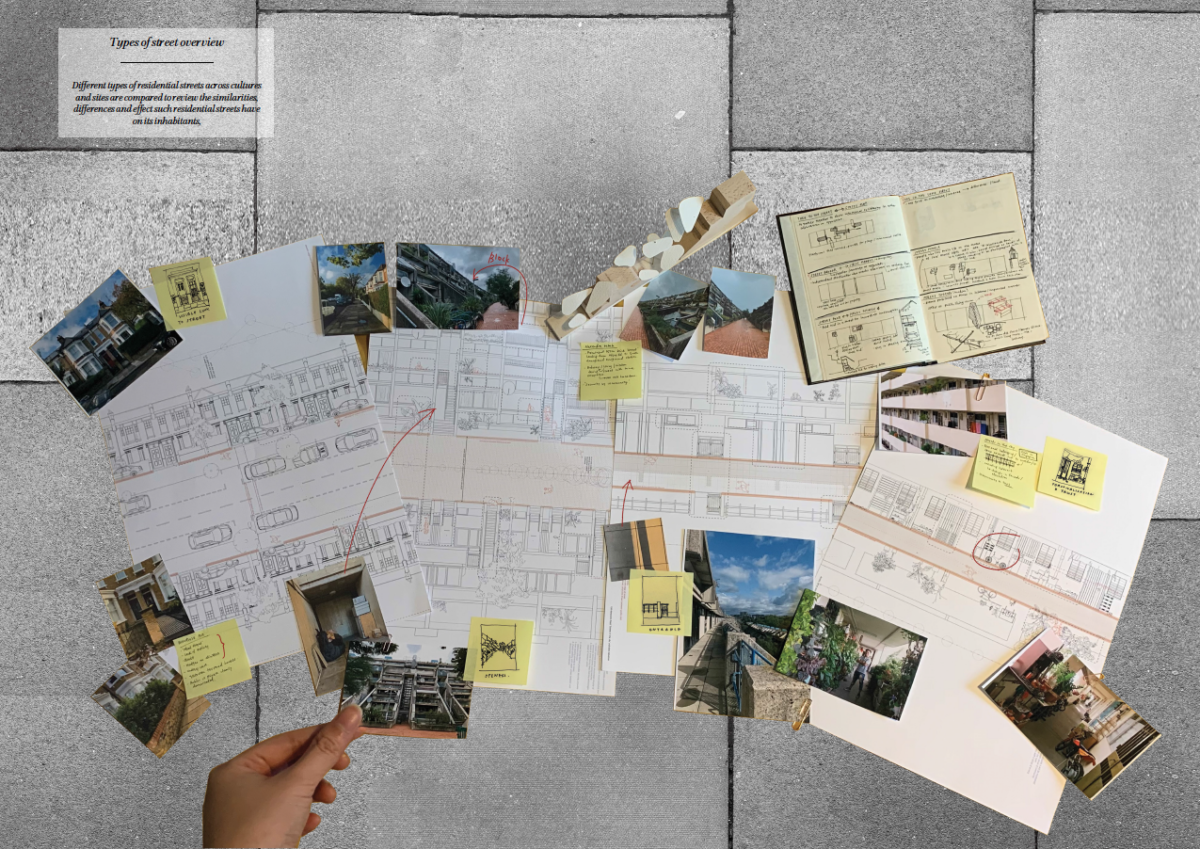

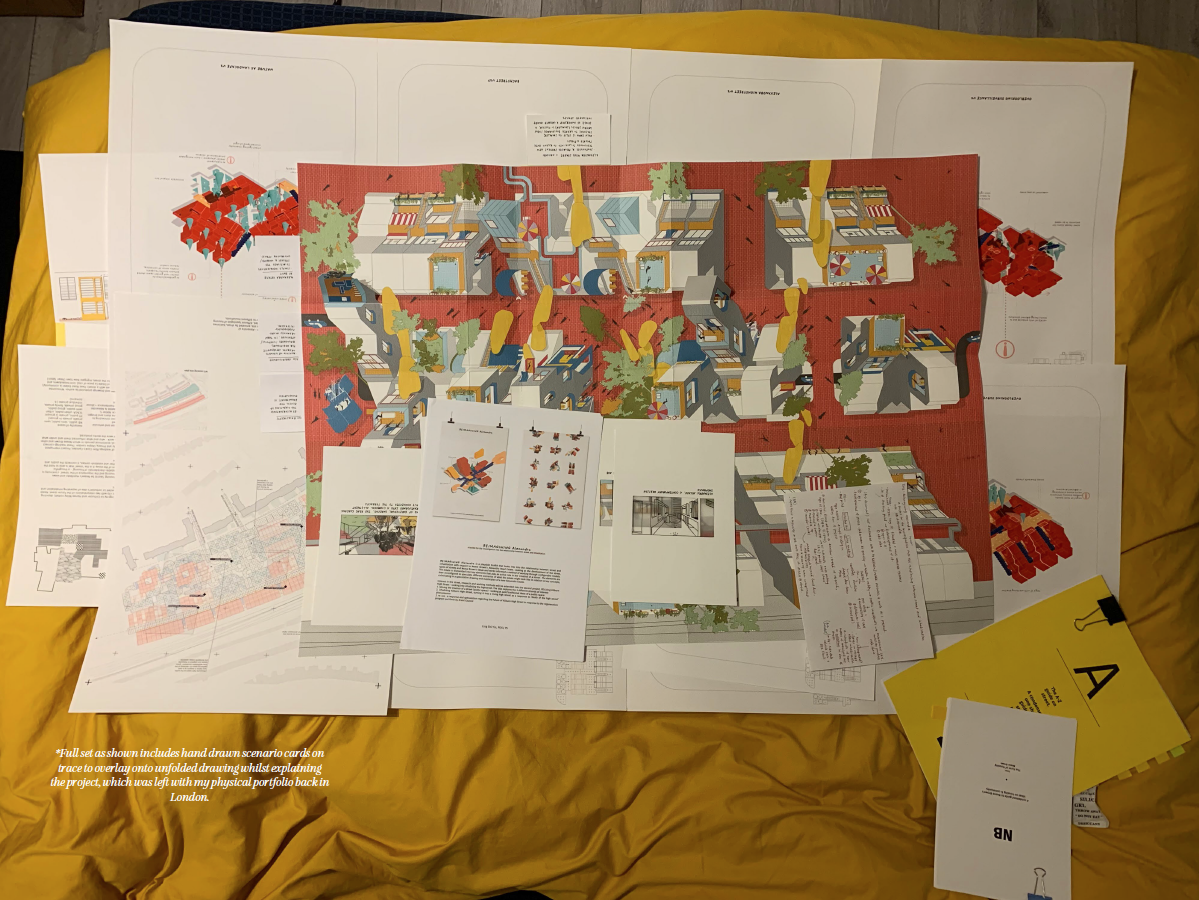

This year Unit PG13 and the Bartlett Living Laboratory has been revisiting a range of urban and rural living concepts. We started the year with a real competition to RE-STOCK the depleting London housing stock. Students were asked to analyse and decode an existing example and develop a new model paradigm – echoing the shifts in society, culture, community and environment.

The ideas identified in the competition formed a seed to explore inhabitation in London further. The new/old paradigms were used to invent a substantial spatial construct set within a real social/urban/rural context. Our students in Unit PG13 tackled inhabitation in London on various scales. The project ranged from extending the Alexandra Road estate, completing Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower ensemble with a self-built high riser, translating the ideas of the Bata Estate in Tilbury into a 21st Century independent community in the flood plains, rethinking Kilburn High Street into a slow street, to a post EU-topia proposal for the borderlands of Luxembourg.

In Unit 13 would like to embark on a journey of speculation. We would like to dream up our own Utopia. Harnessing the optimism embedded in the ideas and bringing them into actually inhabitable spaces. Strictly speaking, your utopia will not be a utopia at all, it will have a ‘place’.

We would like to thank Samson Adjei, Barbara Campbell Lange, Alice Hardy, Sara Martinez, Rae Whittow Williams, Paolo Zaide for their support.

DR tutor Rae Whittow-Williams

Technical consultant Toby Ronalds, EOC Engineers

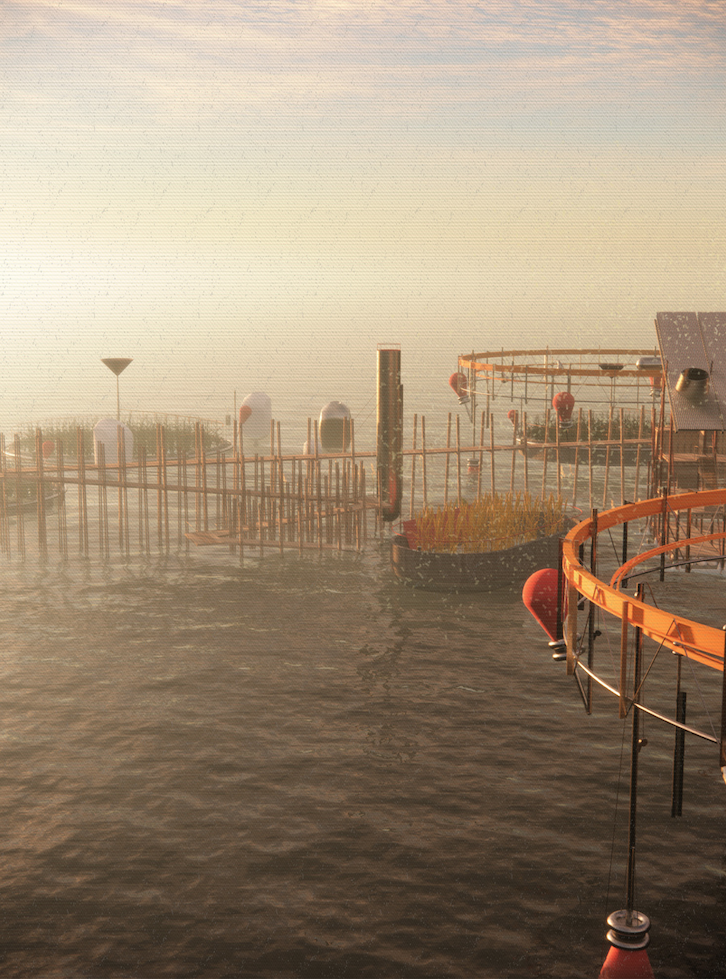

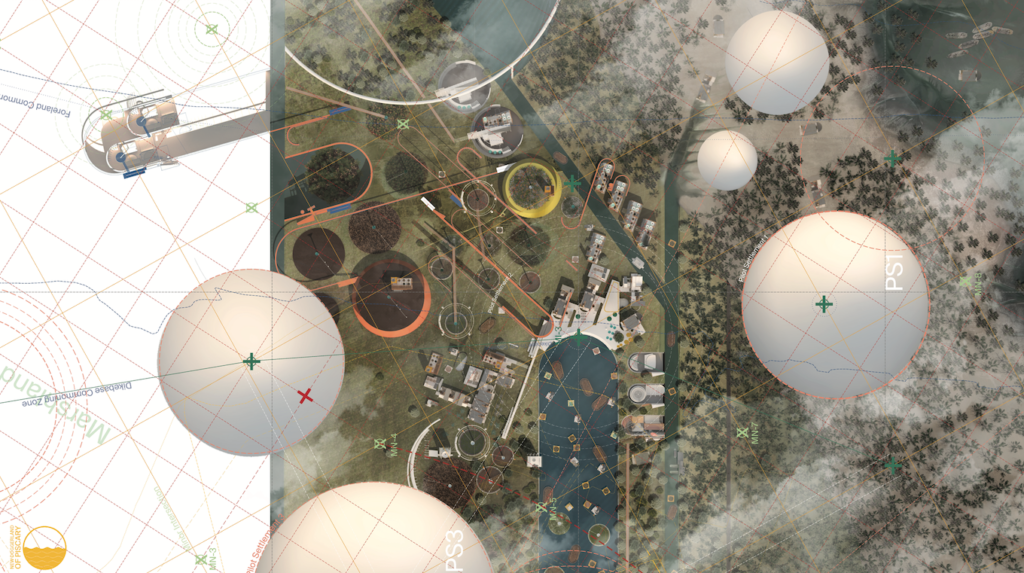

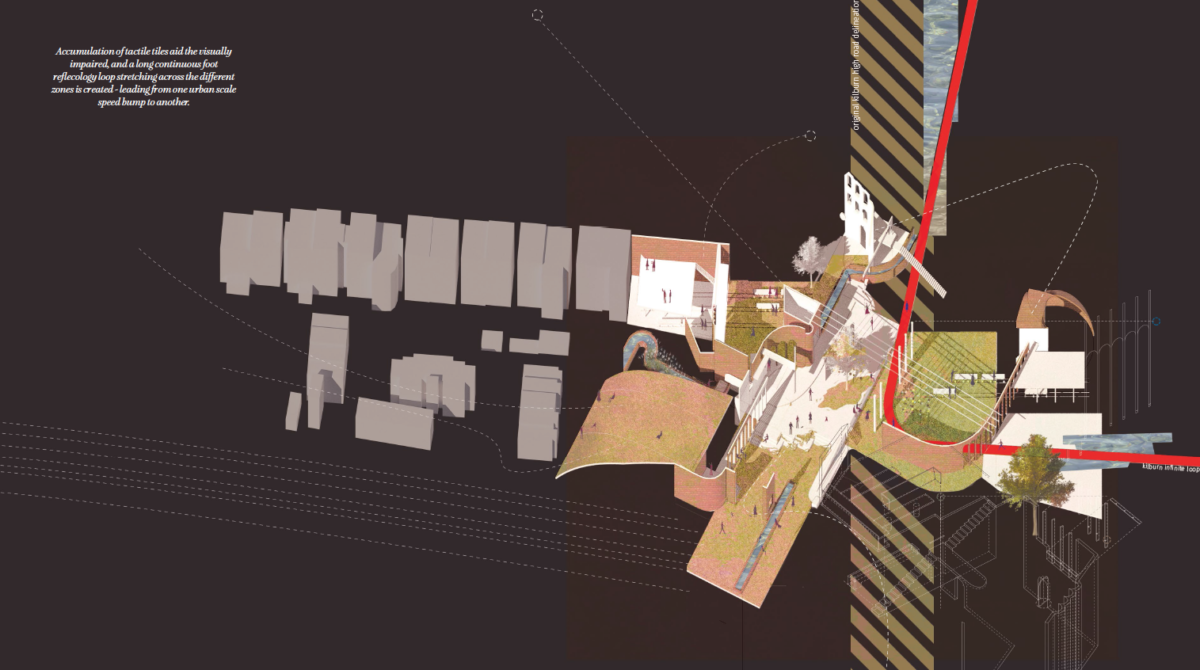

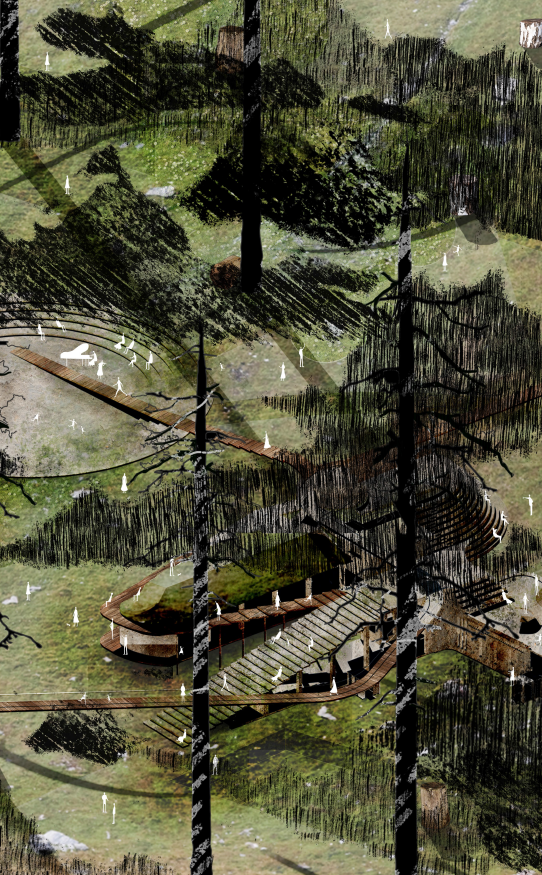

NEW DOGGERLAND

A Dynamic Masterplan for Enabling the Tilbury Commons

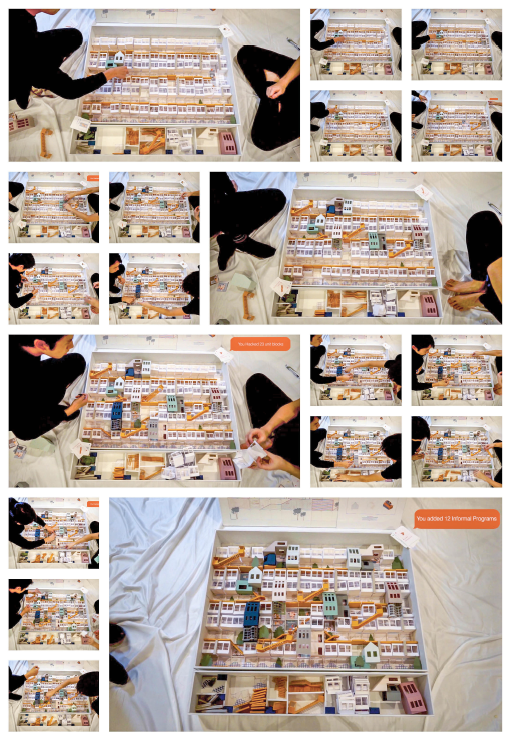

Utilising Kate Macintosh’s Dawson’s Heights in East Dulwich as a catalyst for studying housing and the notion of Utopia, the theoretical mindscape of the thesis project is established through initial readings into Theodor Adorno, who suggests that “Even if one cannot draw a blueprint for utopia, aware-ness of the inadequacy or incompleteness of existing reality depends utterly on belief in the possibility of an alternative” (Adorno, 33).

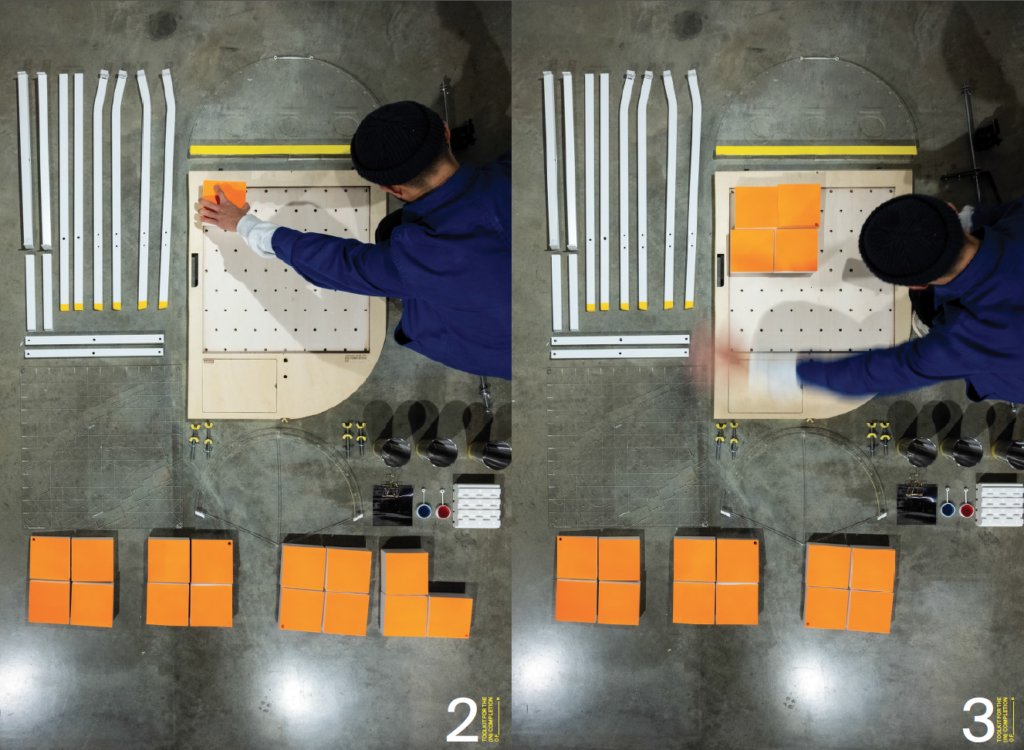

Through an investigation into the multiplicity of “Utopias” that could arise on site, a participatory device that engages with local residents and actors on designing and co-producing these incomplete, and envisioned futures was developed. Taking the form of a collapsible toolkit, it was first tested at Dawson’s Heights to (co)produce responses to speculative reimagining of the estate. Having developed a working methodology in engagement practice, we move to the Bata Estate in East Tilbury, a radical company town which was once at the forefront of live-work relations and modernist construction which has fallen into a state of precariousness and deprivation since the shuttering of Bata Shoes. Through the toolkit, a catalogue of resident’s memories and ambitions for East Tilbury were developed, where the written Thesis develops this into a pluralistic mode of participation that enables multiplicity in urban ambitions and “utopias” to be made visible. As part of a symbiotic discussion, this in-situ research that underpins the development of the New Doggerland was shared with the community to allocate Heritage Funding for their Bata Memories Centre.

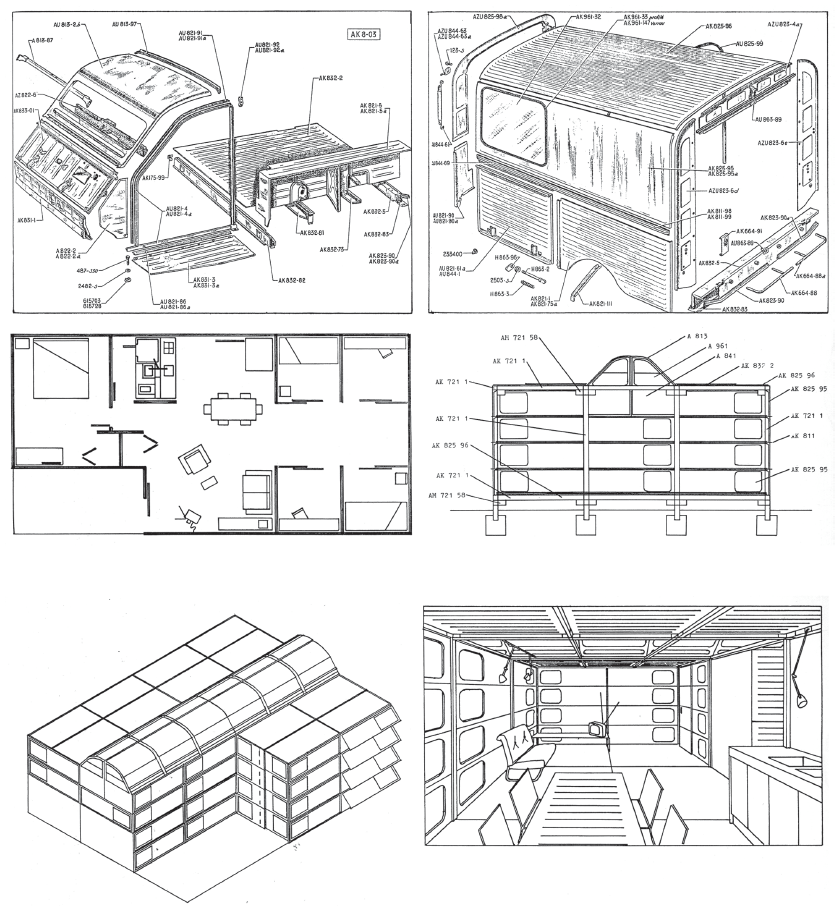

Acknowledging the socio-ecological crises that are resultant of our extreme consumption and resource extraction, a dynamic, reactionary and arguably incomplete “master” plan is proposed… Instead of working against the forces of nature, the comm(o)nity of East Tilbury has long sought to return to a nomadic way of life, forgoing the rampant pressures and excess of the neoliberal city for something more attuned; living with (and not against) the land. Re-turning to principles of the historic commons, their settlement has been designed with the foresight of adapting to change in both land and waterscapes, where the dynamic (master)plan is built across time, seasons and tides to speculate with new forms of living. The riverbank has receded, but unlike predictions in the early 21st Century, the Thames has been deliberately widened as a catalyst. Developing from an initial afforestation of the marshland ecology, a soft system for the production of the commons began, fifty years ago, as a series of ponds, forests, polders and waterways to seed the New Doggerland of today. Driven by the historical principles in Commoning – Of Piscary, Of Estovers and In The Soil, living with the community involves a new relationship to the water/land through seasonal consumption of agriculture and stewardship of the river and forestery – as examples. Learning from Bata’s preconstructed components, the New Doggerland is expanded through a “Common Language”, where moulds and materials are re-used to expand, or decrease spaces according to the population, needs, tidal ecology and environment. Simultaneously safeguarding the historic Bata Estate further inland, the common contemplates on an approach to architecture that is post-compositional, reactionary and embedded within our larger ecological systems, contributing beyond the wellbeing of its inhabitants, but the habitat(s) of the Estuary. Instead of building from (and against) the water, flooding becomes an opportunity – to re-arrange and expand commons living across the Thames to Coastal England.

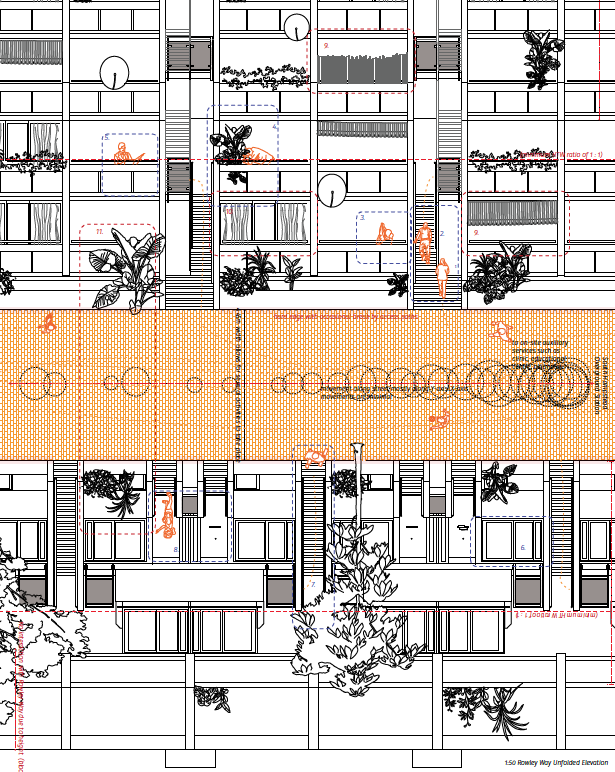

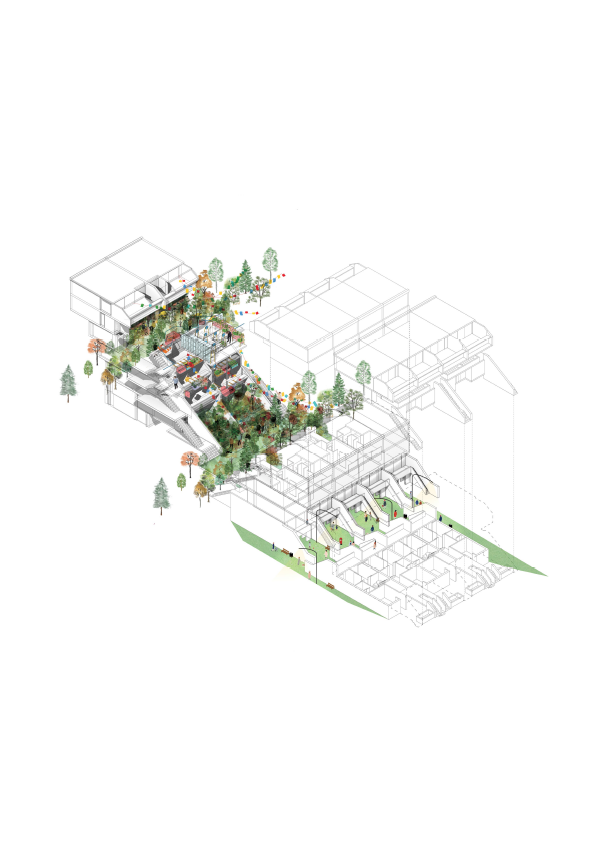

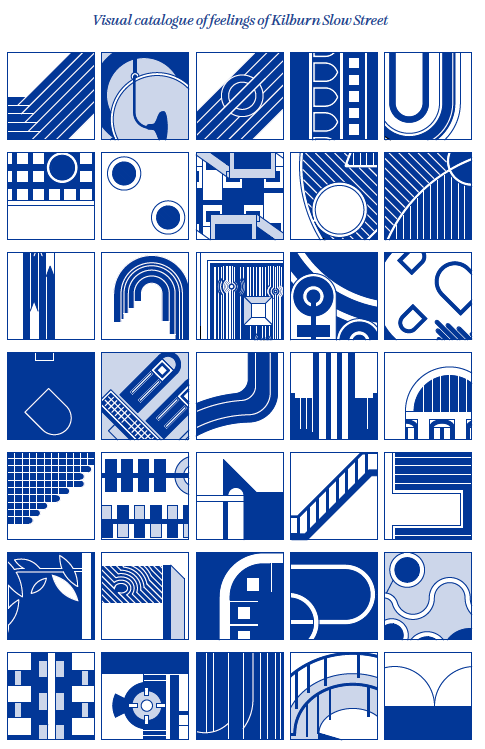

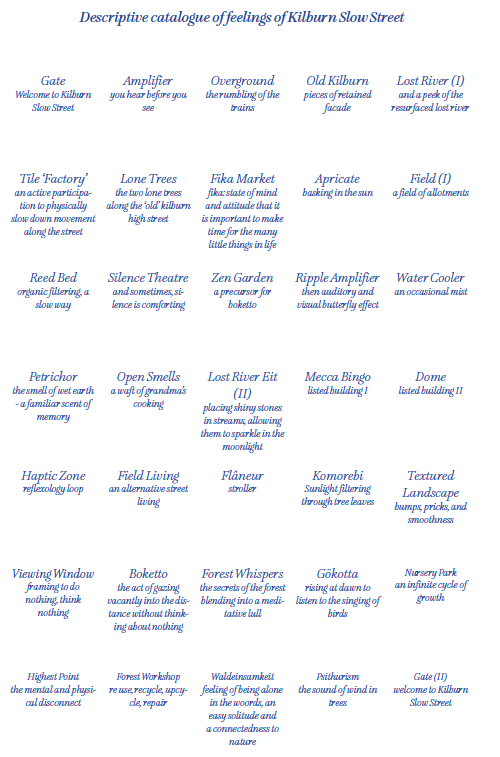

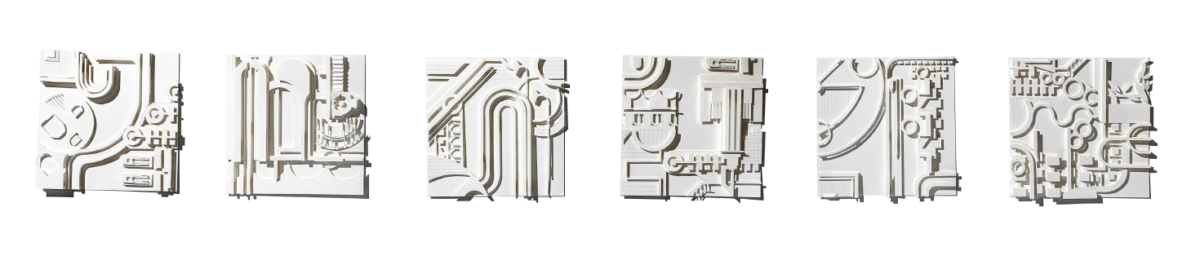

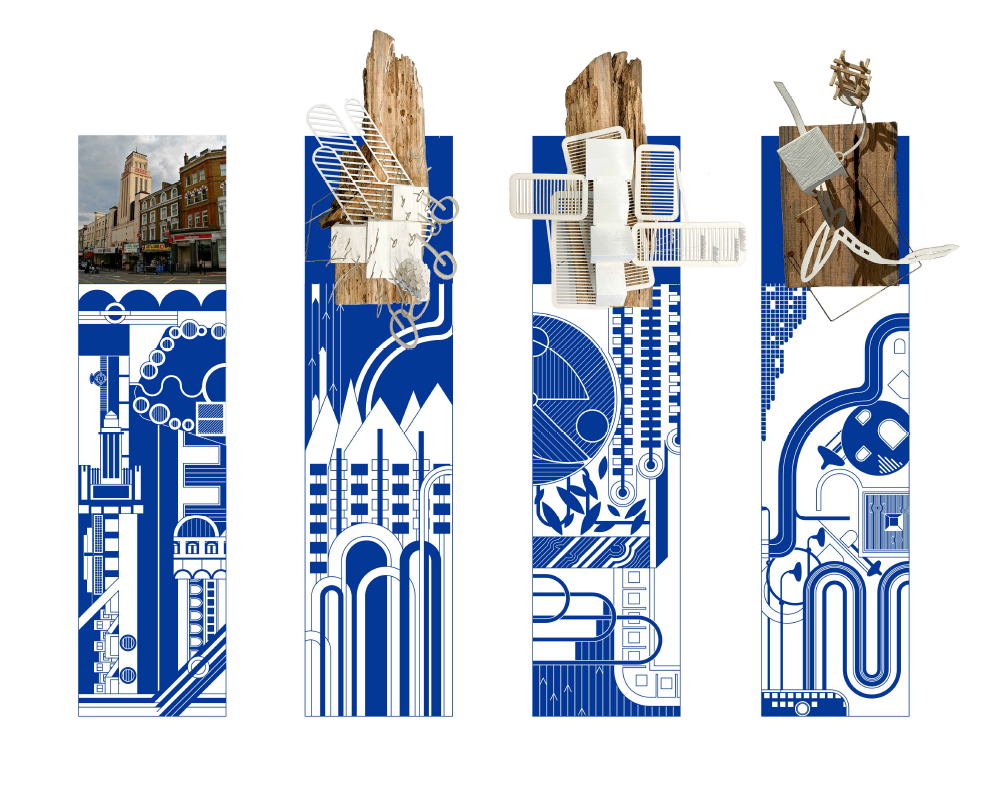

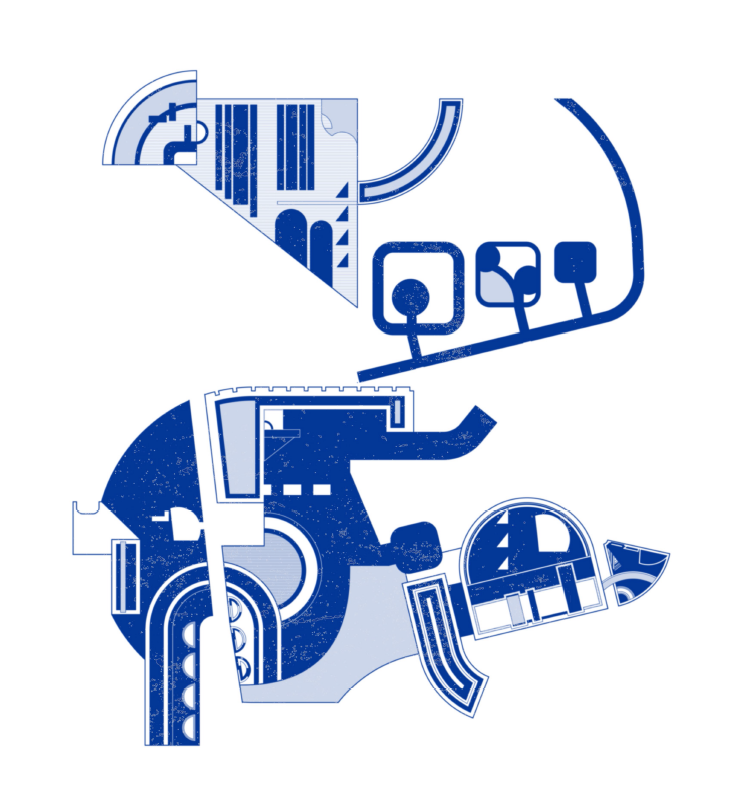

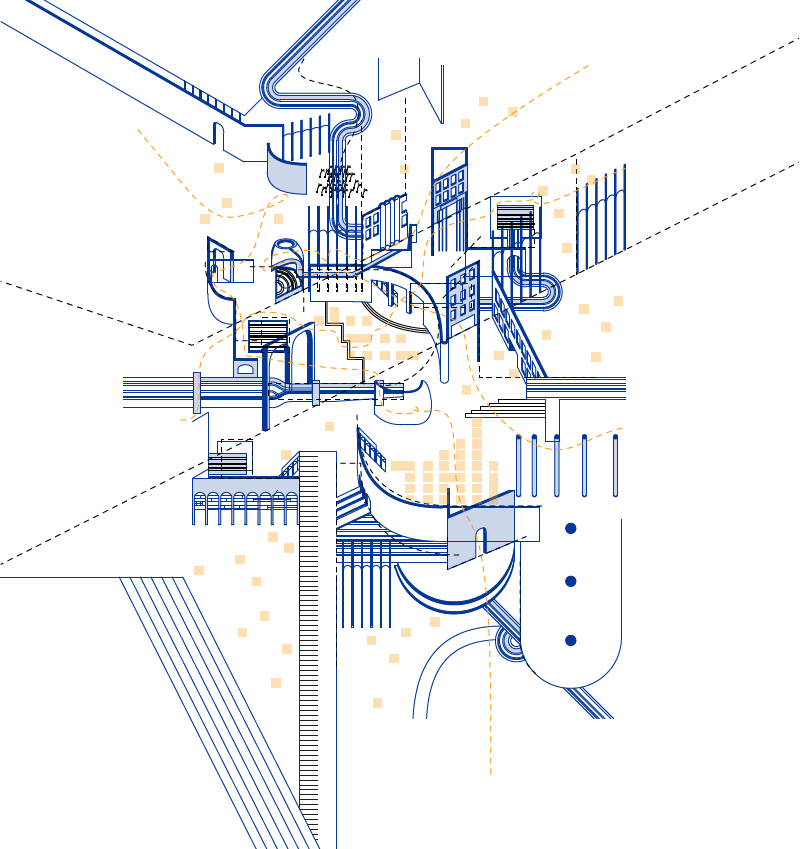

Kilburn Slow Street

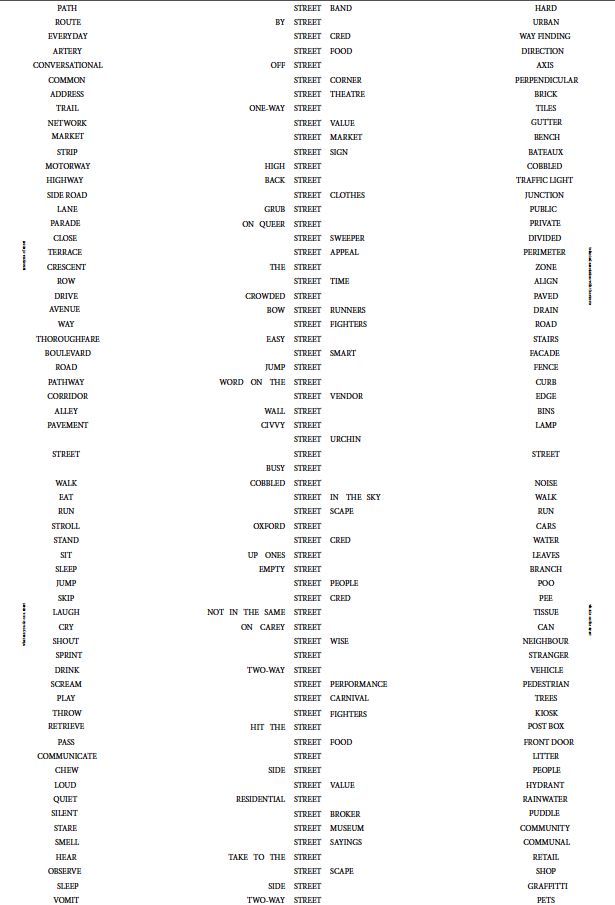

A visual narrative through a play of scales, focusing on the ‘non-physical’ aspects of what makes a street.

A two-part investigation into the overarching question of: what makes a street’, term 1’s investigation into re-imagining Alexandra Road Estate looked at the physical elements of the street while Term 2’s project – Kilburn Slow Street, is a spatial exploration of an alternative narrative for the future high street, focusing on the ‘non-physical’ aspects of the street, and associating with the ideas of deceleration and slowness. The ‘death of the high street’ phenomena is at its peak and the movement from offline to online retail has opened an important discussion of what the future high street can be. The high street which has typically been associated with circulation and retail, will now be synonymous with ‘place’, history, culture and the people.

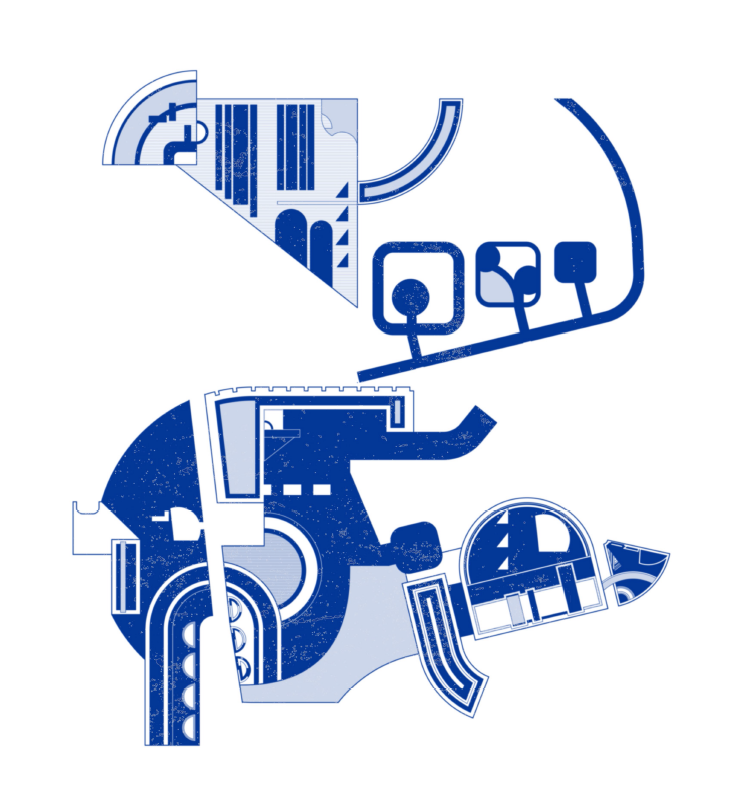

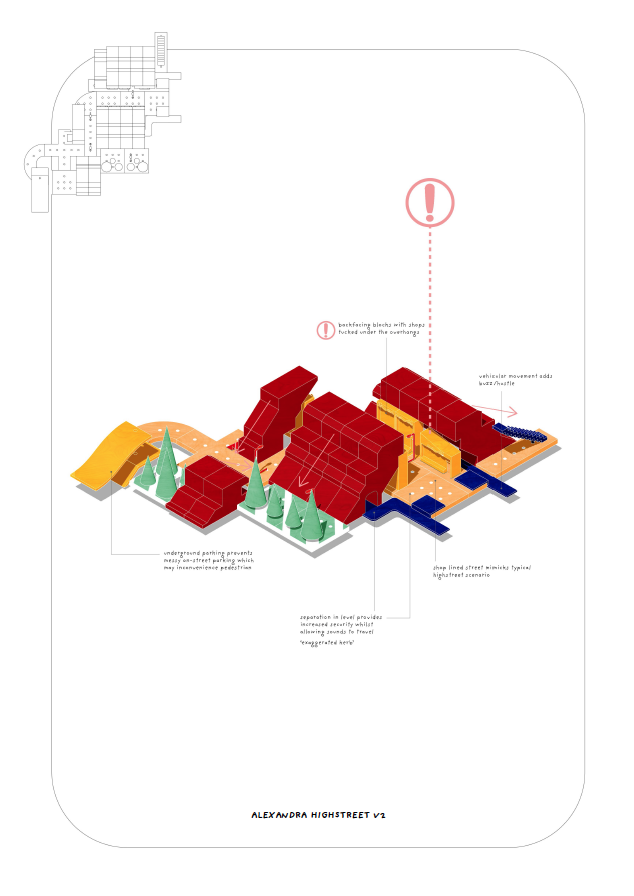

The structure of high streets has roughly remained the same since its inception – a set hierarchy and segregation of buildings, pavement and roads. A recent change to this preconceived notion of the street structure is the implementation of the ‘shared space’ concept on Exhibition Road, resulting in a kerb-free street shared by both motorists and pedestrians. Set in Kilburn High, Kilburn Slow Street takes this concept a step further by speculating a new street typology shared by infrastructure, people and nature, where the ‘street’ unites, rather than divides programmatic spatial relations.

Macro-Architecture, Micro-Urbanism: the project explores a singular set of 1:1 tiles in various scales to re-imagine the new high street – the tile as an object, a spatial moment, a building plan and masterplan.

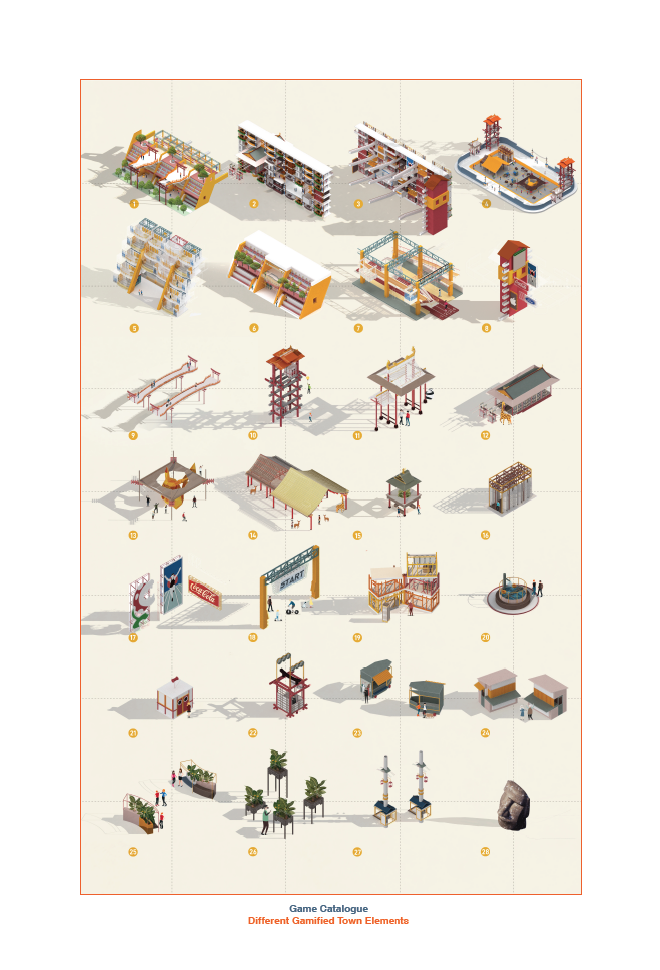

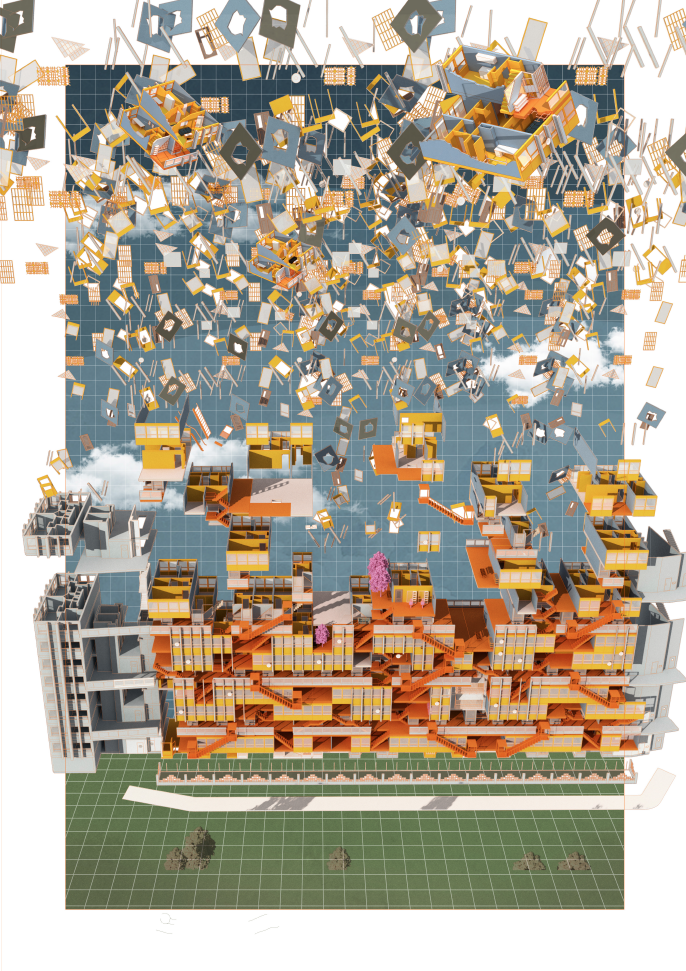

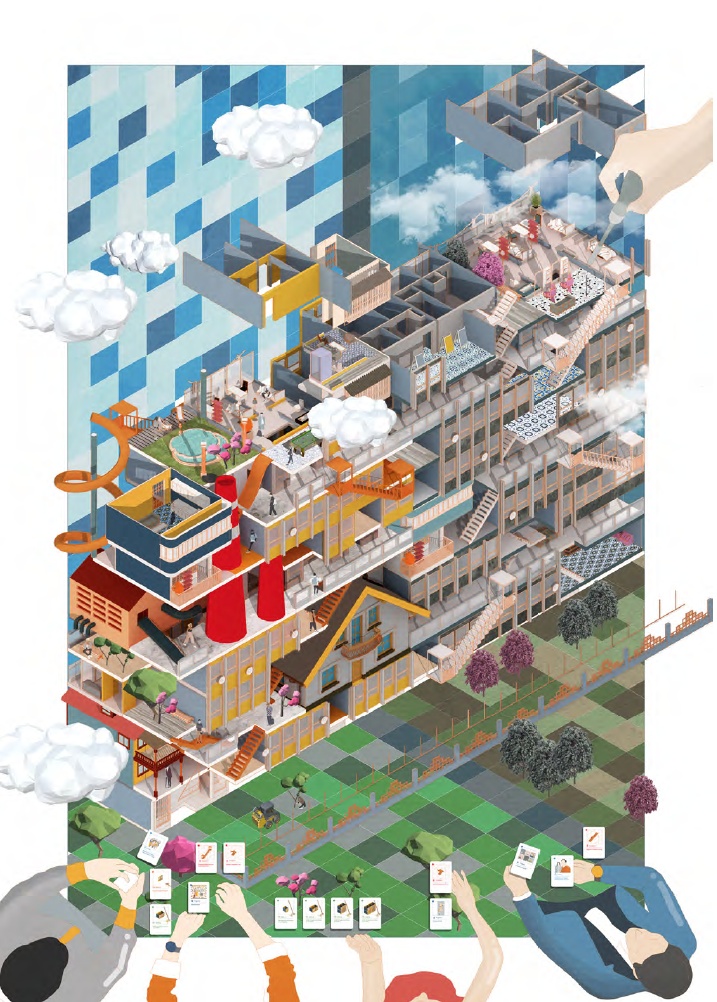

Design by Decoding – an investigation into Gamification as an Architectural Procedur

Hacking RHG

In project 1, I am interested in investigating how gaming ideas could inform new design methodologies. Under the strict building and maintenance rules of social housing in London, a lot of brutalist housing prototypes in London is being restricted and demolished so as to create more housing stock such as the Robin Hood Gardens. I am looking into how gamification would allow collective users (residents) to participate in the design under a bottom-up approach. The approach translates design principles into a board game to reimagine, repurpose and reconfigure spaces and materials found on-site. Besides, it also incorporates a variety of building rules, new addons, informal programs, and a new circulation system to reactivate the lost dream “street in the sky” for Robin Hood Gardens.

In a nutshell, “Hacking RHG” is a testbed showing how gaming can be used as a methodology to explore a different way that residents can engage with architecture. By playing against the rules, the algorithm of the game is turned into a planning system, capable of evaluating the best strategy of the collective bottom-up approach.

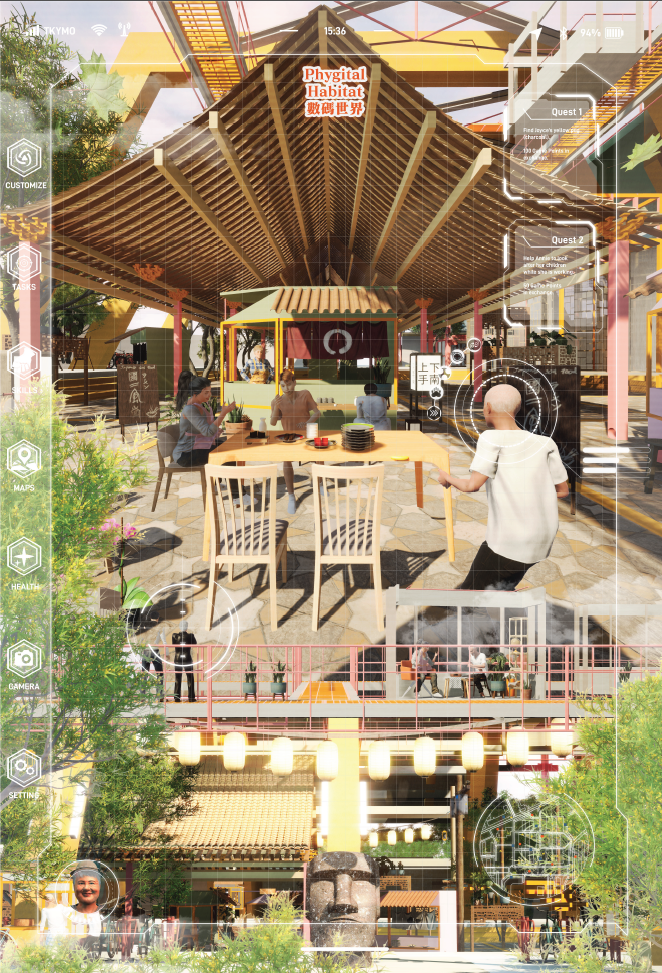

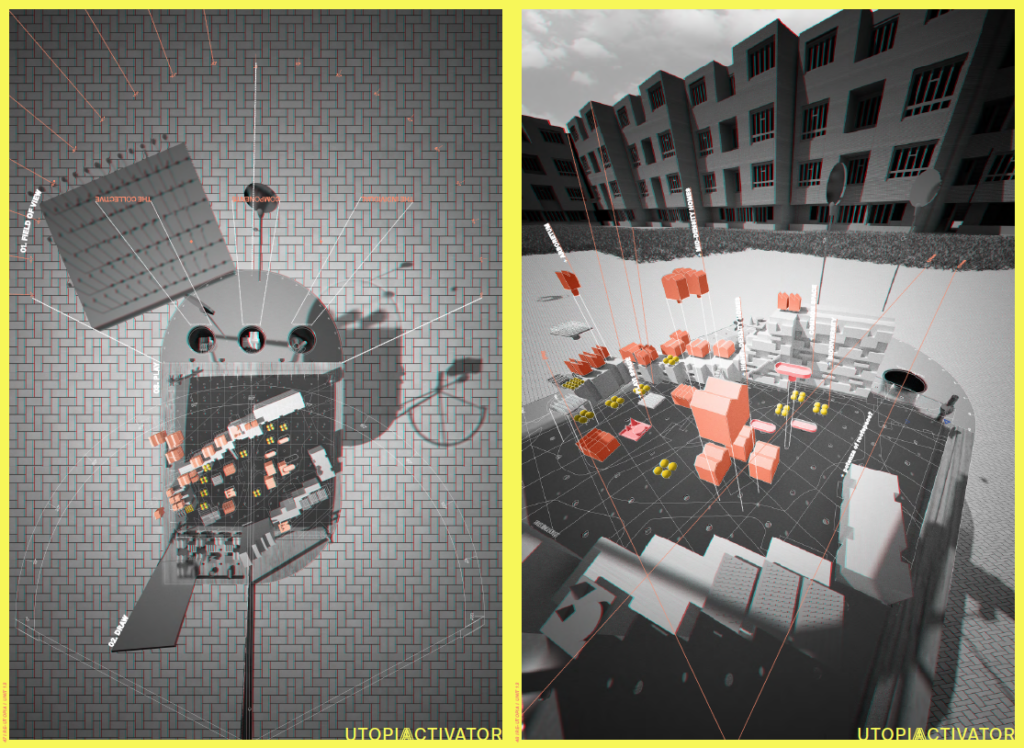

Phygital Habitat

Phygital Habitat uses video game elements and brings them into the physical world to solve real-life dilemmas. Through the introduction of mixed reality and gamification, the project provides a vision to utilize both to bring architecture and community back into life.

In Japan, there is a lot of post-war housing called Danchi. These buildings, once the representation of a generation’s memory and lifestyle, are succumbing to their fate as the nation’s vision of new building policies called for their demolition. The project not only speculates on an alternative way of living, but also saves the existing Danchi. It is a prototype which is capable for everyone, while providing both physical and virtual gaming and living experience.

Watch FILM ON YOUTUBE here: