Category: Featured

Featured projects from across the years

a festival of the mundane

During his lifetime the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer completed around 50 paintings of which 35 survive today. Most of the paintings depict domestic scenes. It is remarkable that 19 were painted in the same room, showing often the same people. The scenes involve normal people doing ordinary things. But looking closer each element has been carefully chosen, playing a predetermined part in an everyday story. The real subjects of Vermeer’s paintings are not the characters depicted; it is the everyday space, the light, the materiality. Being ‘mundane’ is usually not a compliment, it’s seen to be dull, lacking interest or excitement.

This year PG13 will explore the ‘Everyday’ – looking in detail at how we live together and inhabit space, the routines informing architectures. The Everyday doesn’t need to be boring, it is you who must elevate it to greatness using imagination and innovation.

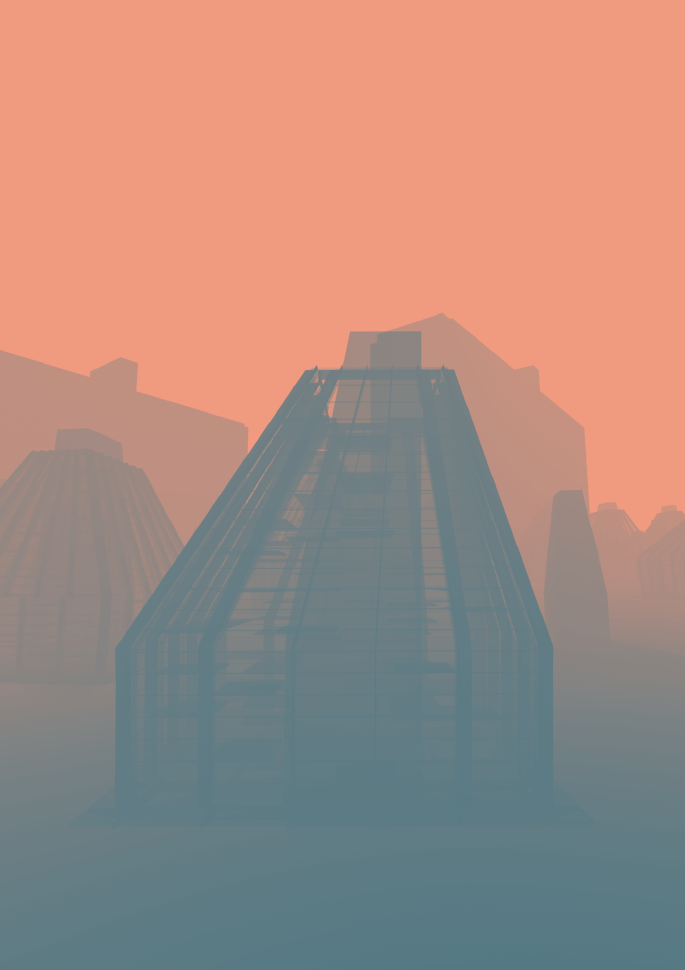

The Embassy of No-land

The project begins by considering how the timely aspect of our constantly changing nature affect our built environment. It is particularly focused on the notion of transitions. This project explores how this type of dynamic, that being a change in environmental or social conditions, could create a stronger symbiosis between the built and natural environment. The project situates itself in the High Arctic, in Svalbard, and takes its inspiration and initiation point in the Svalbard Global Seed bank. A doomsday vault designed to secure our future food supply against any imagined danger. However, like the environment it is situated within, the vault is under threat by the unpredictable long-term geophysical modifications brought about by the melting of ice. The project picks up on these problems and speculates in an alternative future for the vault. This time as an embassy, represented by a new country every year. Through six narratives from different scales and perspectives – the project speculates on how architecture can create a stronger symbiosis with the natural environment that it inhabits. As a results, it creates an infrastructure built on the natural transitions and an architecture which are growing and eroding with the seasonal and social changes.

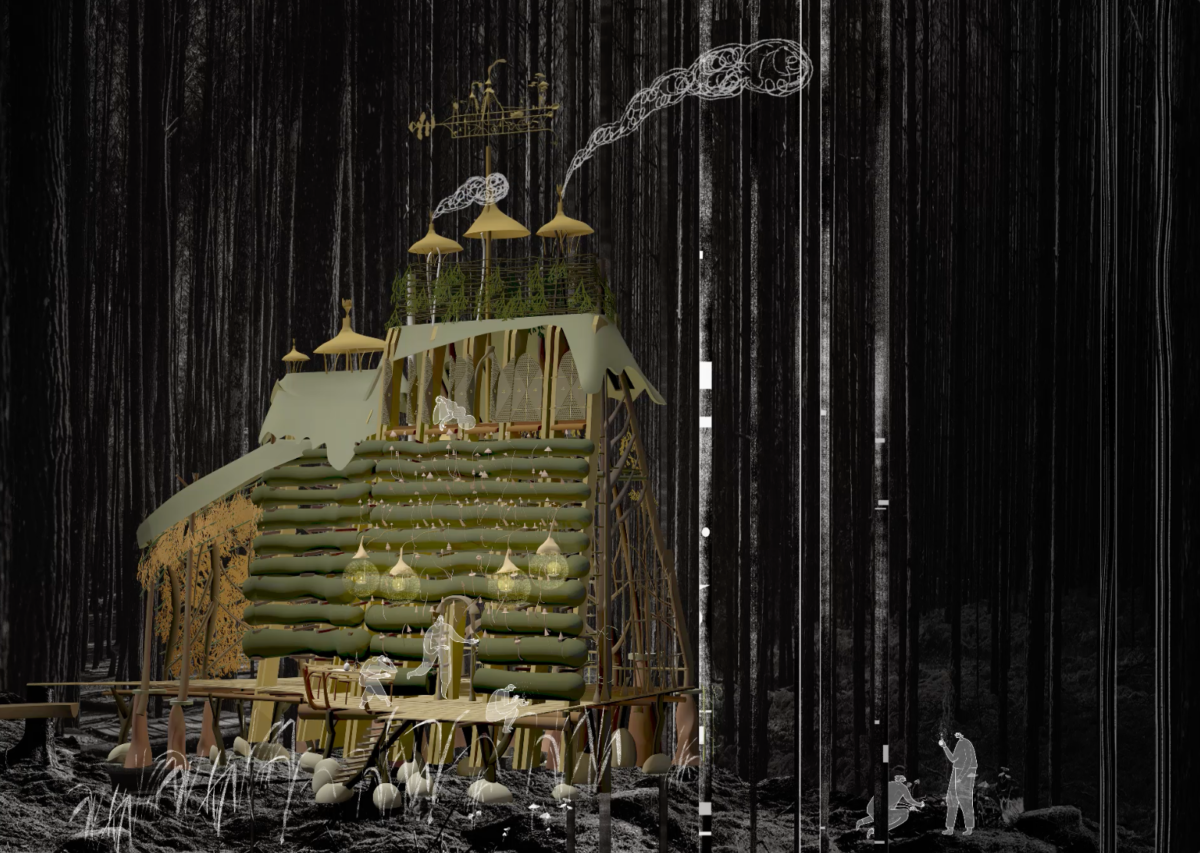

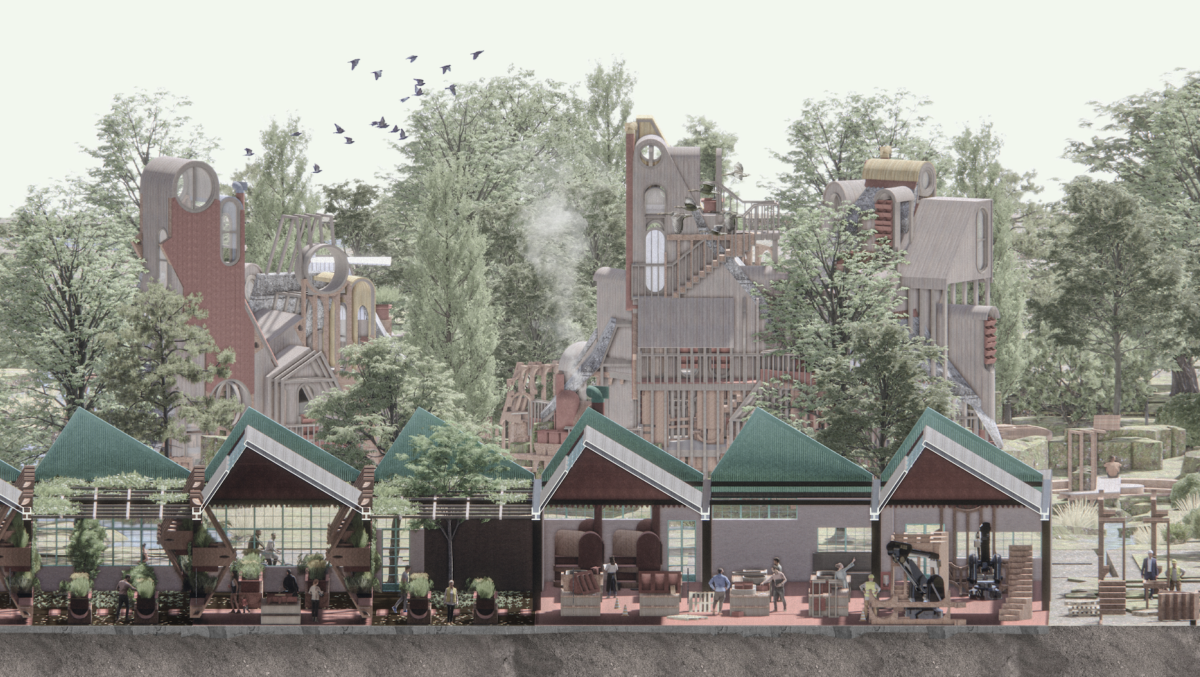

Crafting a Lithuanian forest: A journey of making oneself in a cultural landscape

‘Crafting a Lithuanian Forest’ examines a reciprocal relationship between people and the forest, through the practice of traditional woodworking that is concerned with who the maker is becoming, and what it is in the making. The project is a commentary on industrial forest practices that take place in the Lithuanian territory of the Curonian Spit, which is protected by UNESCO World Heritage as a unique cultural landscape. It was developed with relentless human efforts over a hundred years to manage natural geomorphological processes—shifting sand dunes. This Lithuanian forest, like many others, is suffering from clear-cutting that is destroying centennial trees and their unique ecosystems. Time for this cultural landscape is running out, and its forest needs urgent social care. The project introduces hand-carved forest structures, that enable people to experience the forest, reminding us of our caring responsibilities: to maintain, restore and sustain. From delicately carved pines that were shaped by shifting sand, to the hand-crafted window and door hinges, all celebrate the cultural landscape, where everything that came from the forest remains in the forest. Storytelling becomes a form of sharing this craft-based knowledge through intergenerational interactions, that create a future for an old-growth forest.

Virtually Public

What does it mean to be in public? The reality of public spaces is one of urban desertification in favour of private virtual spaces, handing the scale of human interaction within the city over to machine learning and algorithm control. Sited in Somerstown’s dwindling use of formal public space, and speculates a public realm where the public rules by siting a virtual townhall within the future expiration of Story Garden’s meanwhile tenure. Although it appears in physical reality as a public retreat, it is transformed through an augmented reality to become a townhall, taking an integrated form of two parts where one reality suggests the existence of the other. The proposed become speculations into asking how the civic, social, and virtual constructs of future publicness alters the nature of who we are and how we interact in public space, how we gather local information and meanings of civic symbolism. It uses real-time interactive game technologies to test user(human) freedom of determination and ultimately asks if the private development of digital technologies can indeed make a space virtually public.

The New Rural

Radical change is needed to evolve the way in which we inhabit our natural world. The evidence is damning, it is already too late to stop our changing climate. By 2050 the effect of rising temperatures, increased flooding and extreme weather will make our existing built environment unfit for inhabitation.

The New Rural is a manifesto, guide and proposition for the necessary realisation of Arcadia in Britain. Looking to the past century, there have been radical movements that idealise the countryside as a canvas for new ideas; just outside of London, to the east, Essex stands as a test bed for these radical rural ideas. The New Rural turns to Essex as a case study to prove the efficacy of the rural once more. The culmination of The New Rural has been an effort to undesign Essex by providing a guide to a settlement typology. This typology is based on a new model for the Faceted Family, an amorphous model based on our communal relationships to each other and to the nature that surrounds us. The New Rural establishes a guide to allow communities to construct their own Arcadia, a utopia in the British countryside.

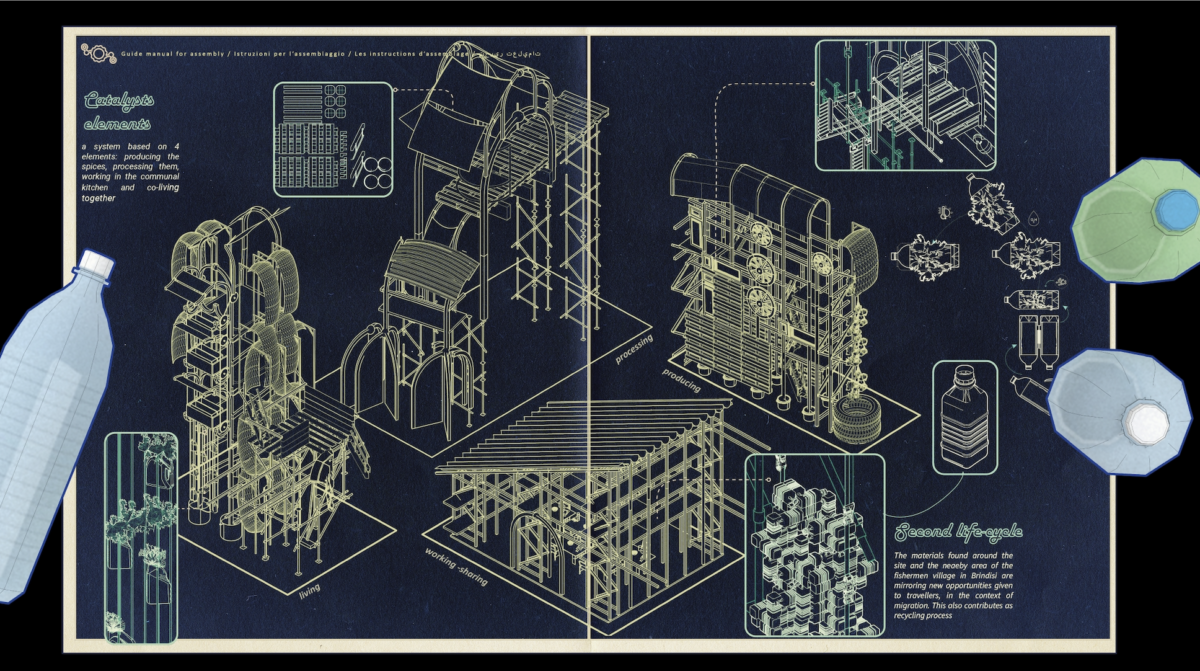

Collegio Reborn

The project, Collegio Reborn, looks at a new way of using collectives of materials that, through up-cycling systems, can mirror the interaction of different groups of individuals with the hosting The project, Collegio Reborn, looks at a new way of using collectives of materials that, through up-cycling systems, can mirror the interaction of different groups of individuals with the hosting territory. The project also investigates the new role of the architect as a mediator among different entities and authorities, done through phases. The engagement with community latches upon participatory tools, eventually associated with individuals’ specialism. The second phase focuses on the making and self-building aspect that integrates parts of the existing building with new living components. The third phase is a social act led by the community, preserving the independence as well as the collaborative spirit of the different groups coexisting and working in the makers’ hub as well as in the communal kitchen. Indeed, Collegio Reborn uses the city of Brindisi to revitalise a neglected part of the city – offering an opportunity for a collective rebirth, not always peaceful and rather tumultuous. Owing to the above, the city of Brindisi becomes the future New European Bauhaus capital, as its scheme best represent the key points of the movement: inclusivity, environmental benefits and a new collective design approach.

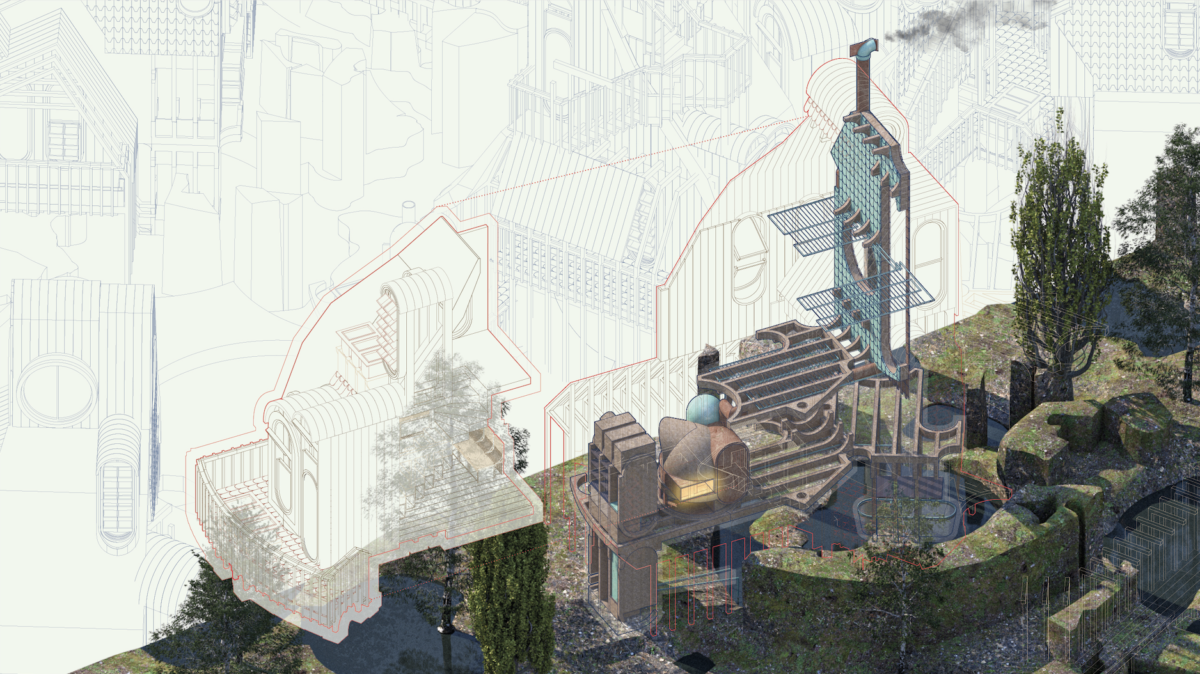

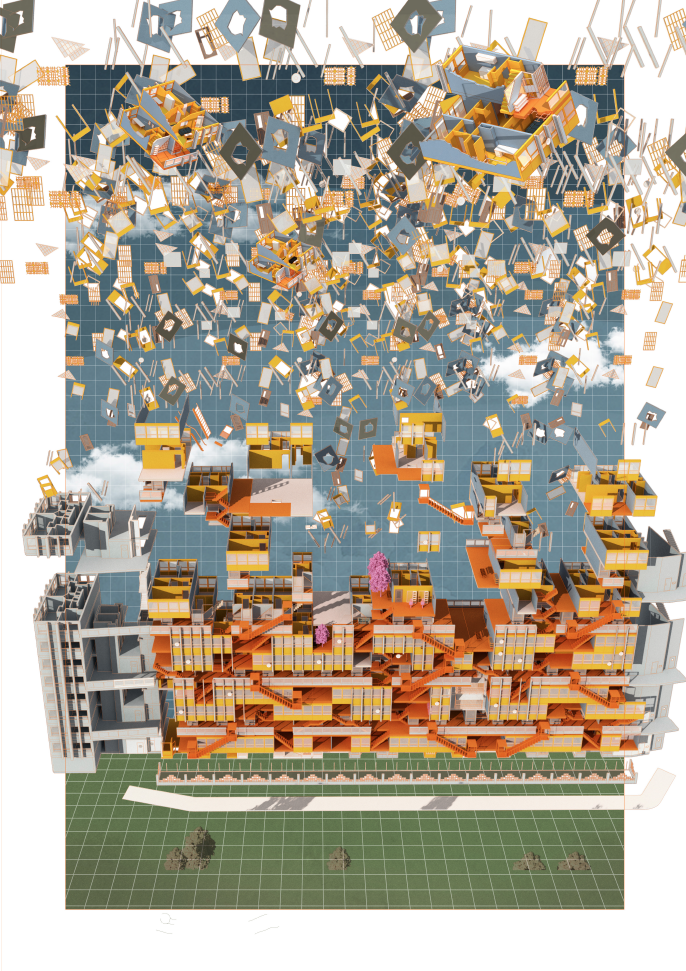

Emergent Heartland

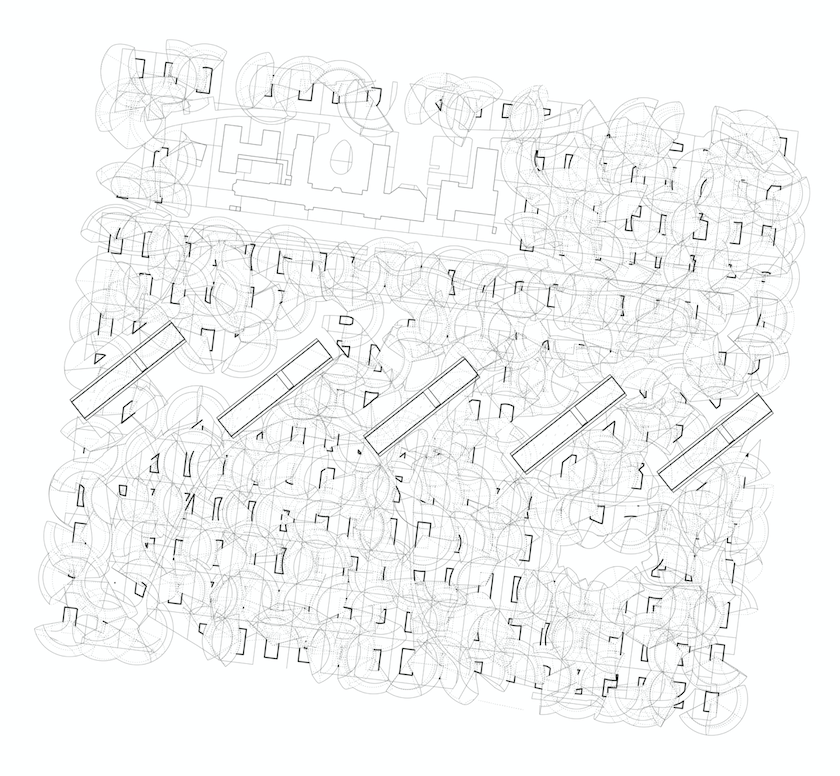

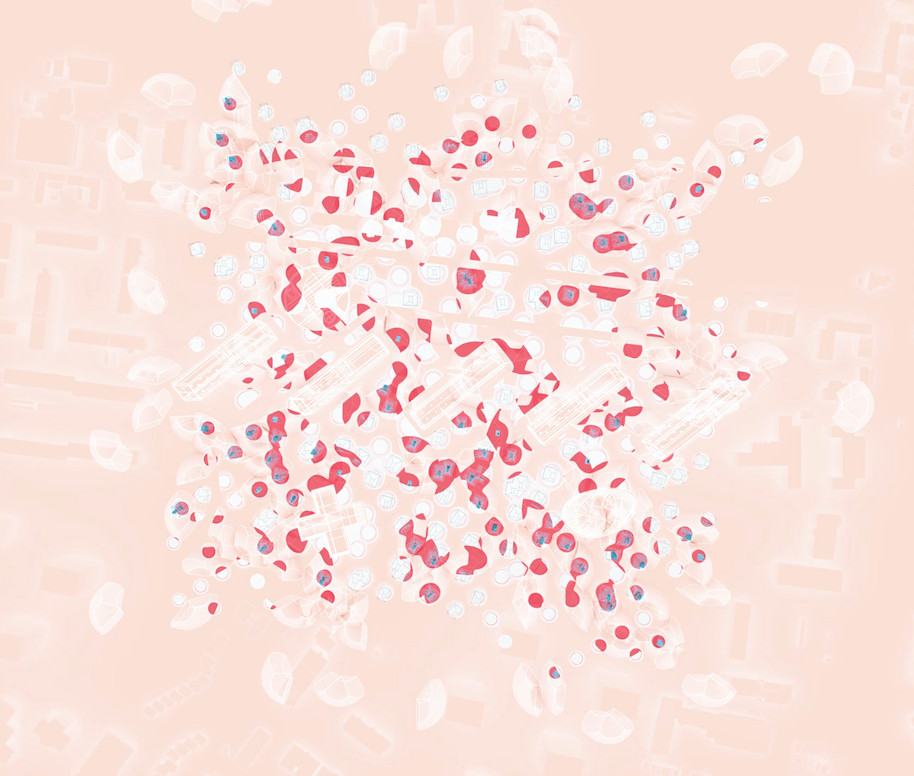

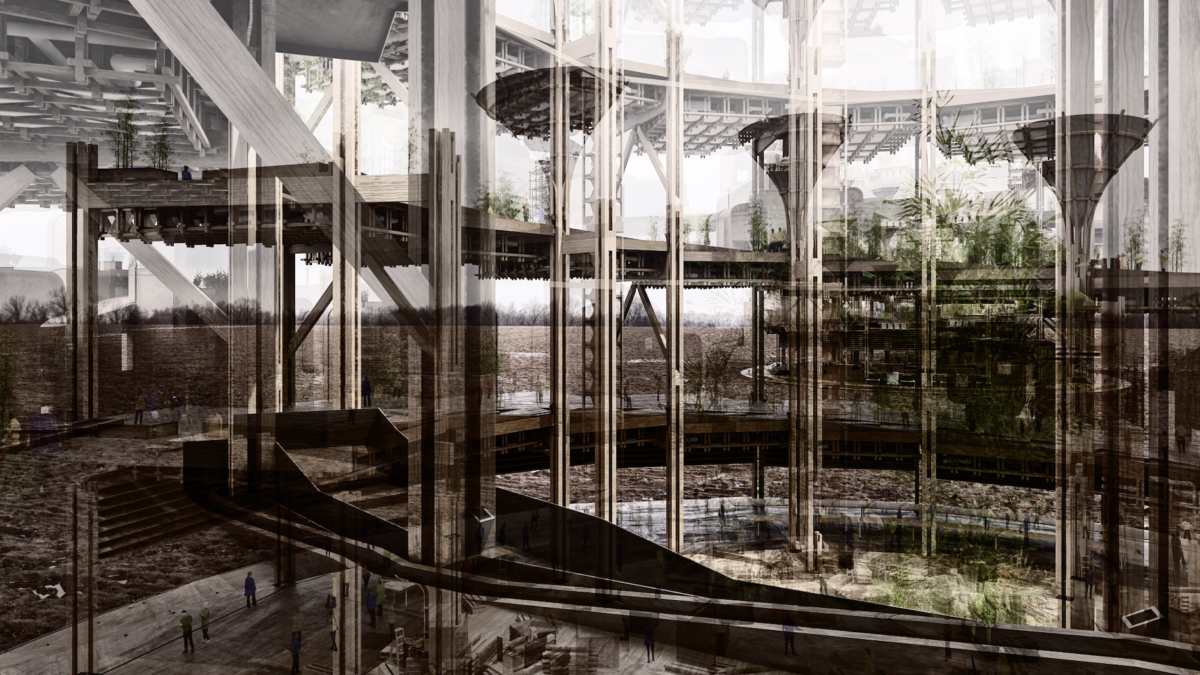

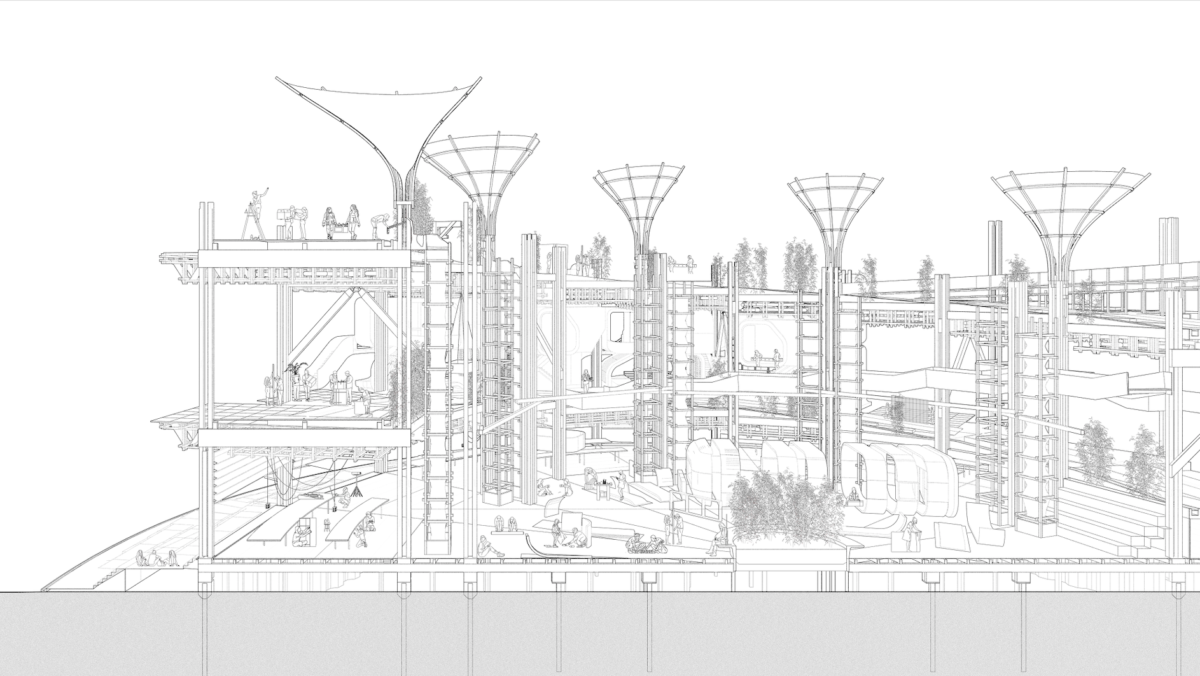

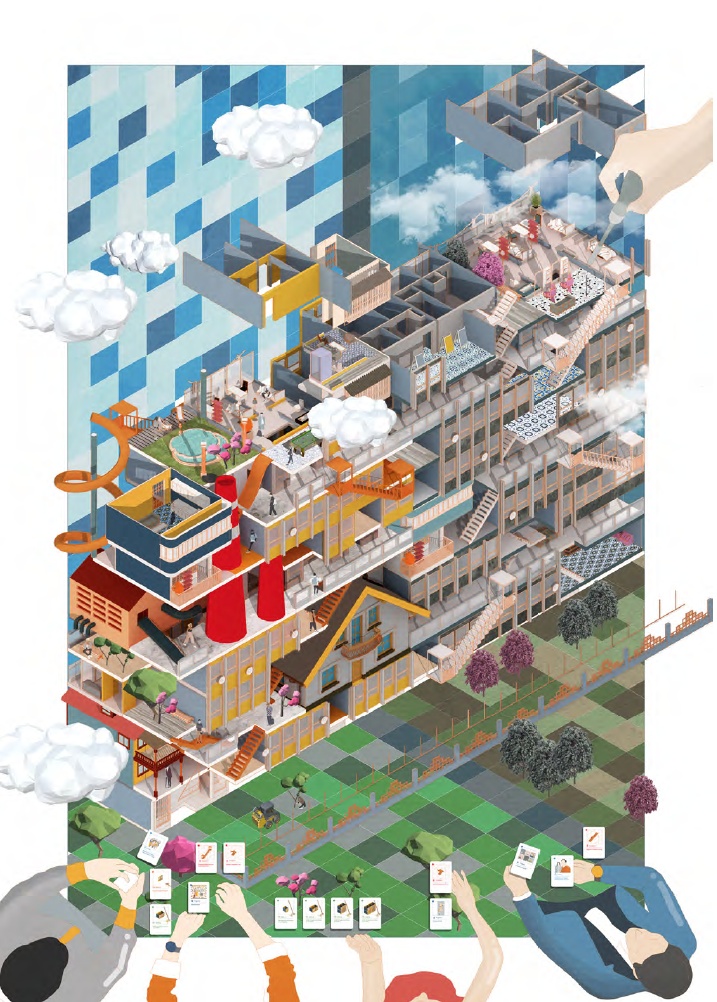

Emergent Heartland is a masterplan that focuses on facilitating bottom-up self-directed urbanism. Made from a kit of parts that are constructed in the central workshop space, the building will grow and adapt over time.

Situated in a brownfield site directly south of the Bata industrial estate in East Tilbury, in the London Greenbelt. Serving as the town’s former industrial Heartland, the factories have since fallen into decay following the Bata shoe factories withdrawal from the area. The scheme draws parallels with this industrial legacy by upskilling and empowering the residents of the building.

Modification, addition and subtraction are central to the buildings approach. Each floor represents a complex negotiated urbanism, where the hierarchy of the built environment process is reversed, and the residents are free to build their own futures. The framework structure includes the overall structural system and floorplates that house the MEP elements. This provides maximum flexibility for the self-builders making construction and deconstruction simpler for those less experienced in the built environment. Ultimately the flexibility provided by the scheme draws parallels with architects such as Walter Siegel and Frie Otto. They saw the architect as a nurturer to empower people to build according to their own needs.

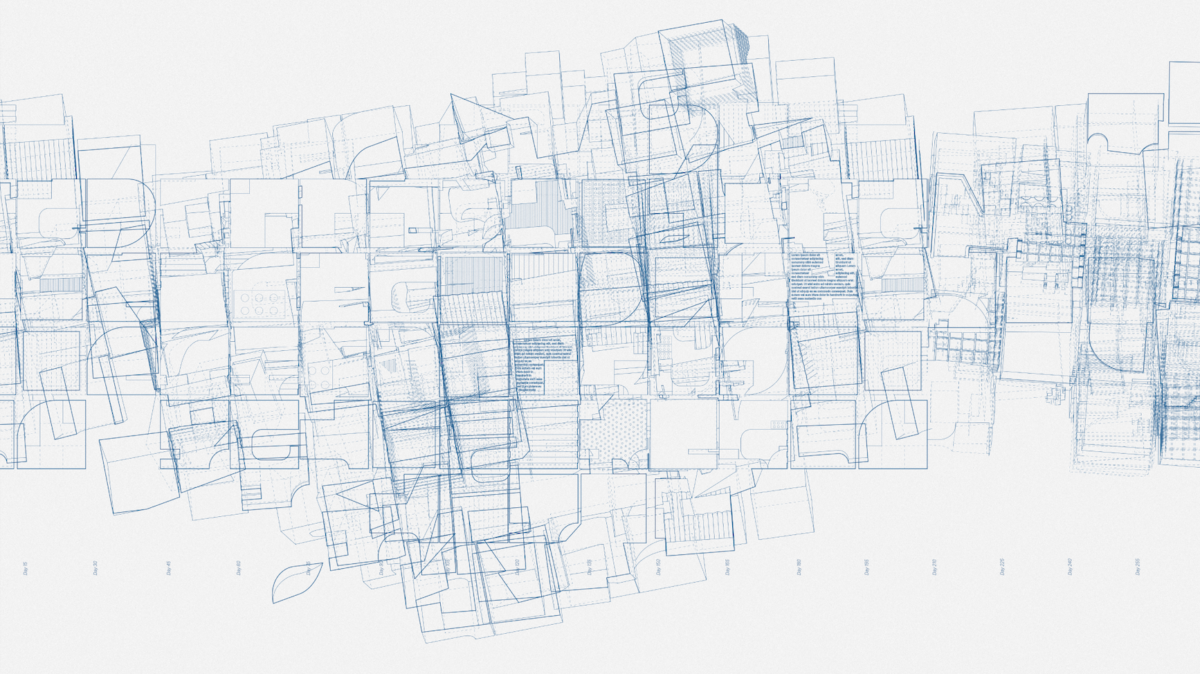

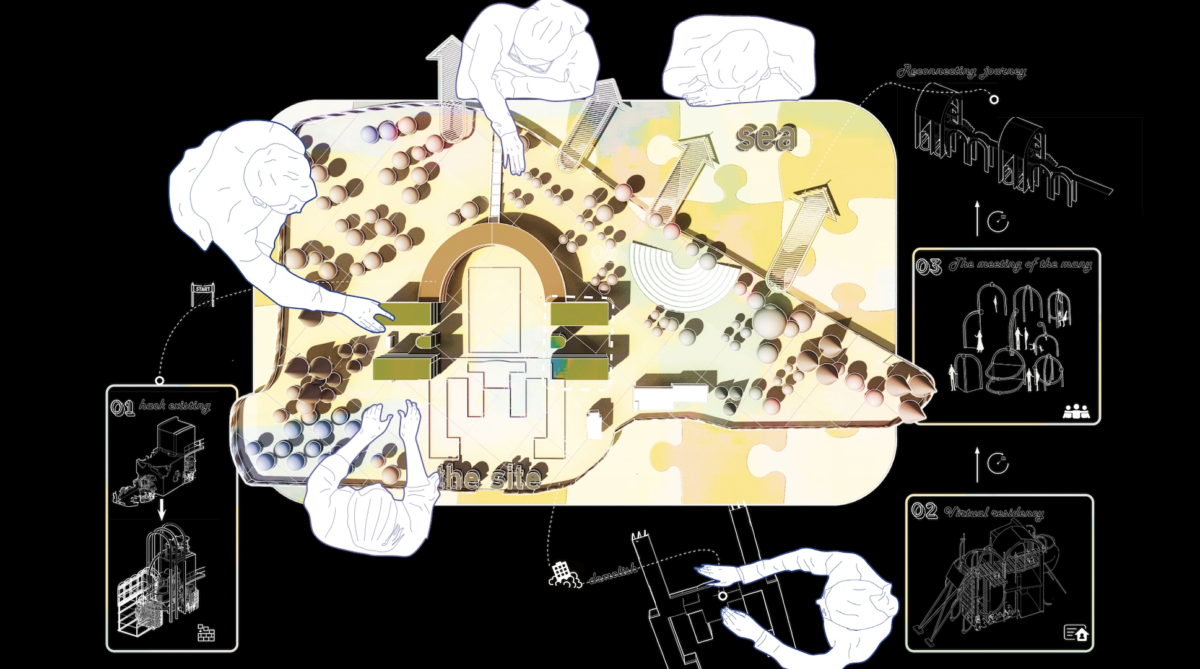

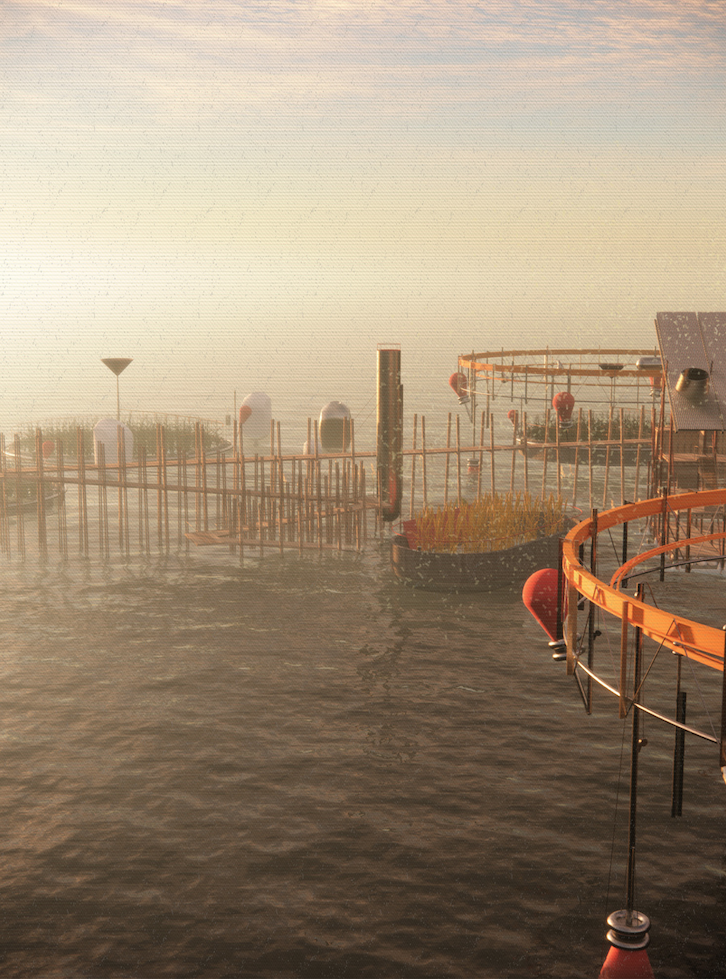

NEW DOGGERLAND

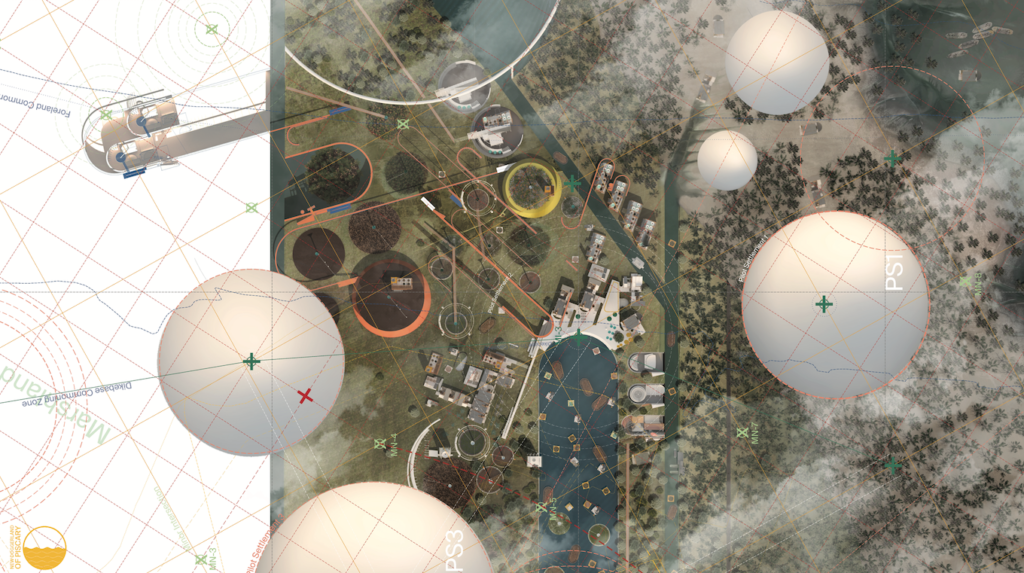

A Dynamic Masterplan for Enabling the Tilbury Commons

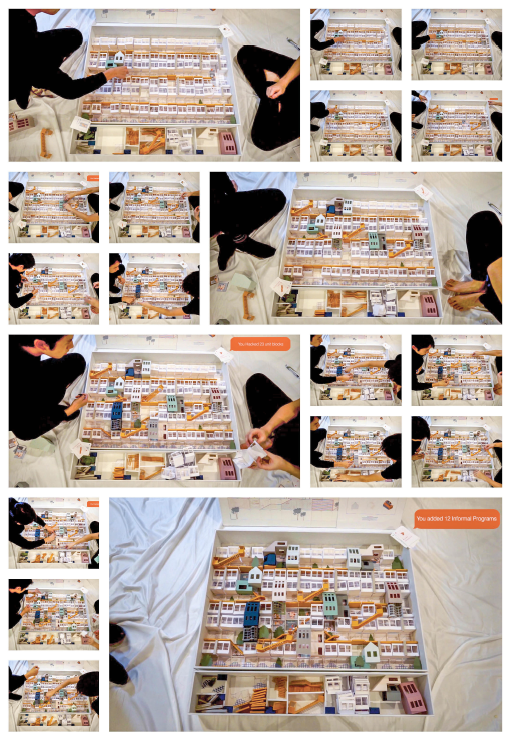

Utilising Kate Macintosh’s Dawson’s Heights in East Dulwich as a catalyst for studying housing and the notion of Utopia, the theoretical mindscape of the thesis project is established through initial readings into Theodor Adorno, who suggests that “Even if one cannot draw a blueprint for utopia, aware-ness of the inadequacy or incompleteness of existing reality depends utterly on belief in the possibility of an alternative” (Adorno, 33).

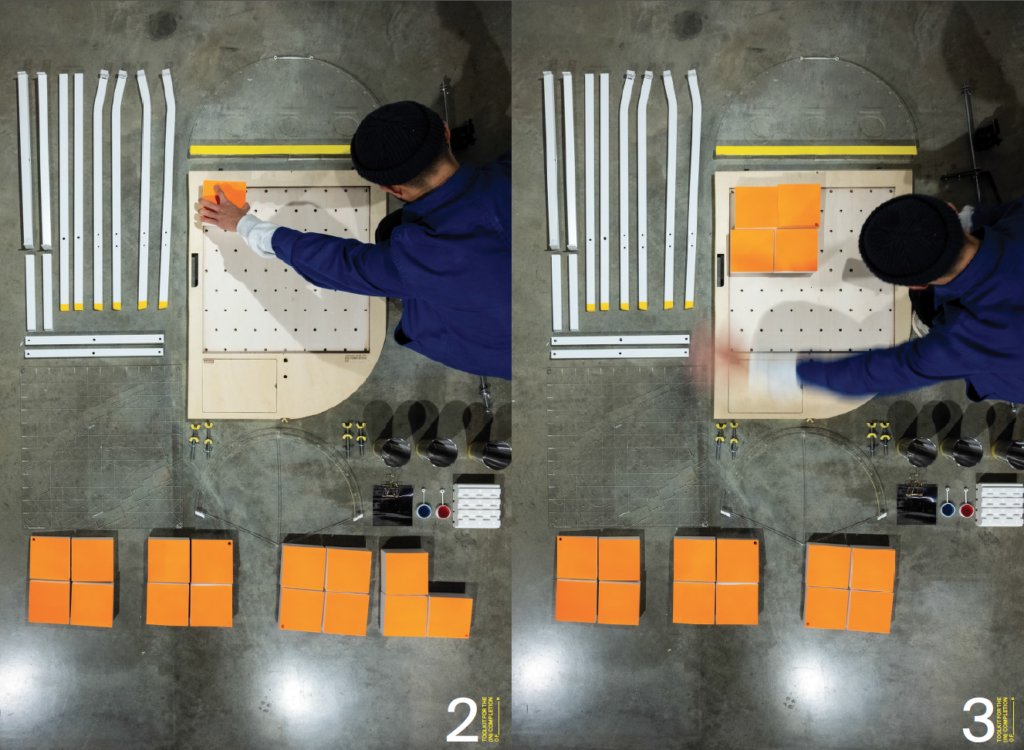

Through an investigation into the multiplicity of “Utopias” that could arise on site, a participatory device that engages with local residents and actors on designing and co-producing these incomplete, and envisioned futures was developed. Taking the form of a collapsible toolkit, it was first tested at Dawson’s Heights to (co)produce responses to speculative reimagining of the estate. Having developed a working methodology in engagement practice, we move to the Bata Estate in East Tilbury, a radical company town which was once at the forefront of live-work relations and modernist construction which has fallen into a state of precariousness and deprivation since the shuttering of Bata Shoes. Through the toolkit, a catalogue of resident’s memories and ambitions for East Tilbury were developed, where the written Thesis develops this into a pluralistic mode of participation that enables multiplicity in urban ambitions and “utopias” to be made visible. As part of a symbiotic discussion, this in-situ research that underpins the development of the New Doggerland was shared with the community to allocate Heritage Funding for their Bata Memories Centre.

Acknowledging the socio-ecological crises that are resultant of our extreme consumption and resource extraction, a dynamic, reactionary and arguably incomplete “master” plan is proposed… Instead of working against the forces of nature, the comm(o)nity of East Tilbury has long sought to return to a nomadic way of life, forgoing the rampant pressures and excess of the neoliberal city for something more attuned; living with (and not against) the land. Re-turning to principles of the historic commons, their settlement has been designed with the foresight of adapting to change in both land and waterscapes, where the dynamic (master)plan is built across time, seasons and tides to speculate with new forms of living. The riverbank has receded, but unlike predictions in the early 21st Century, the Thames has been deliberately widened as a catalyst. Developing from an initial afforestation of the marshland ecology, a soft system for the production of the commons began, fifty years ago, as a series of ponds, forests, polders and waterways to seed the New Doggerland of today. Driven by the historical principles in Commoning – Of Piscary, Of Estovers and In The Soil, living with the community involves a new relationship to the water/land through seasonal consumption of agriculture and stewardship of the river and forestery – as examples. Learning from Bata’s preconstructed components, the New Doggerland is expanded through a “Common Language”, where moulds and materials are re-used to expand, or decrease spaces according to the population, needs, tidal ecology and environment. Simultaneously safeguarding the historic Bata Estate further inland, the common contemplates on an approach to architecture that is post-compositional, reactionary and embedded within our larger ecological systems, contributing beyond the wellbeing of its inhabitants, but the habitat(s) of the Estuary. Instead of building from (and against) the water, flooding becomes an opportunity – to re-arrange and expand commons living across the Thames to Coastal England.

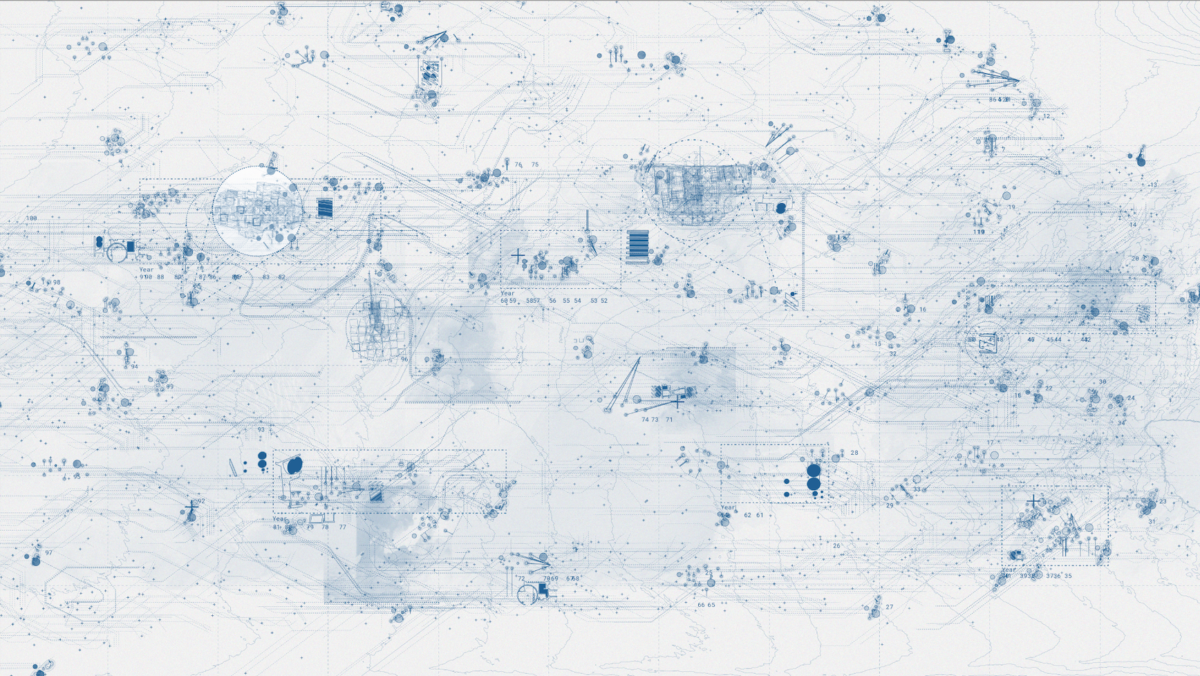

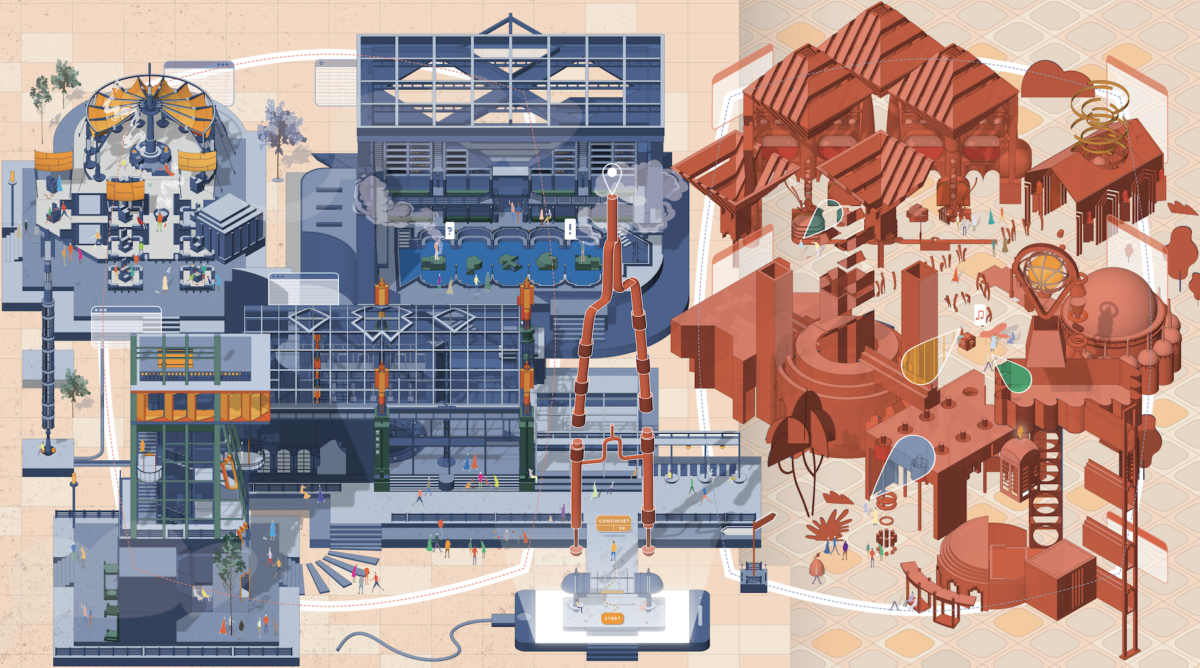

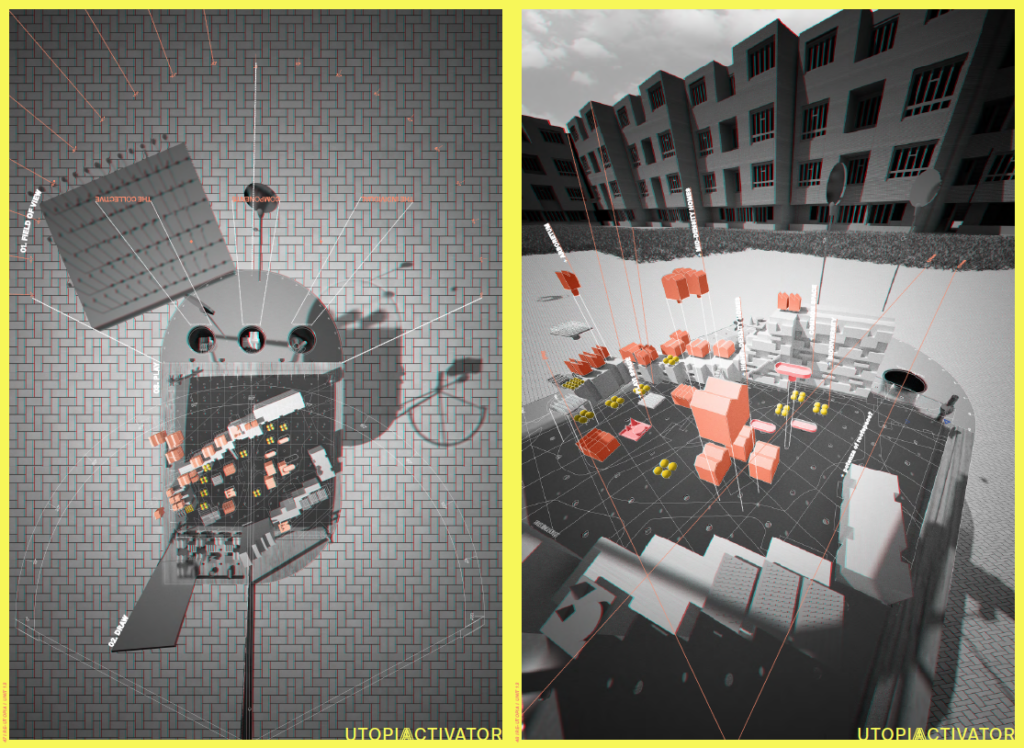

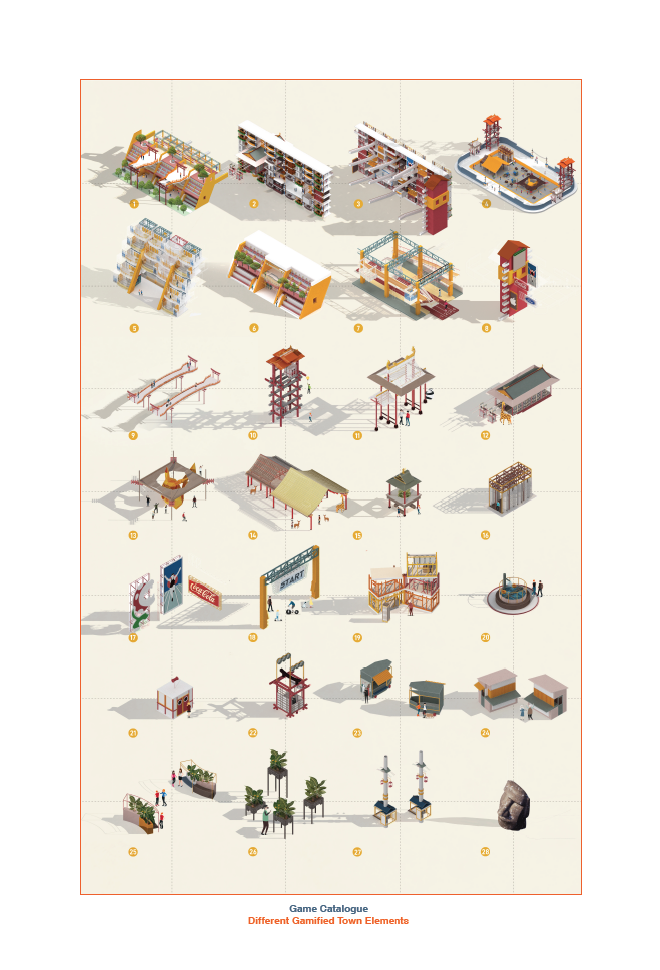

Design by Decoding – an investigation into Gamification as an Architectural Procedur

Hacking RHG

In project 1, I am interested in investigating how gaming ideas could inform new design methodologies. Under the strict building and maintenance rules of social housing in London, a lot of brutalist housing prototypes in London is being restricted and demolished so as to create more housing stock such as the Robin Hood Gardens. I am looking into how gamification would allow collective users (residents) to participate in the design under a bottom-up approach. The approach translates design principles into a board game to reimagine, repurpose and reconfigure spaces and materials found on-site. Besides, it also incorporates a variety of building rules, new addons, informal programs, and a new circulation system to reactivate the lost dream “street in the sky” for Robin Hood Gardens.

In a nutshell, “Hacking RHG” is a testbed showing how gaming can be used as a methodology to explore a different way that residents can engage with architecture. By playing against the rules, the algorithm of the game is turned into a planning system, capable of evaluating the best strategy of the collective bottom-up approach.

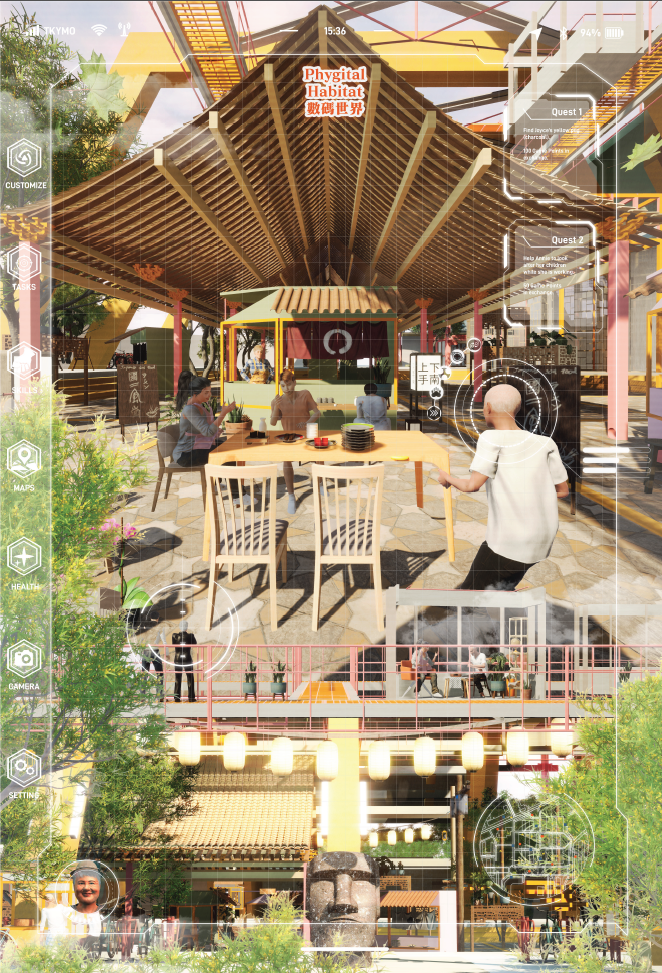

Phygital Habitat

Phygital Habitat uses video game elements and brings them into the physical world to solve real-life dilemmas. Through the introduction of mixed reality and gamification, the project provides a vision to utilize both to bring architecture and community back into life.

In Japan, there is a lot of post-war housing called Danchi. These buildings, once the representation of a generation’s memory and lifestyle, are succumbing to their fate as the nation’s vision of new building policies called for their demolition. The project not only speculates on an alternative way of living, but also saves the existing Danchi. It is a prototype which is capable for everyone, while providing both physical and virtual gaming and living experience.

Watch FILM ON YOUTUBE here:

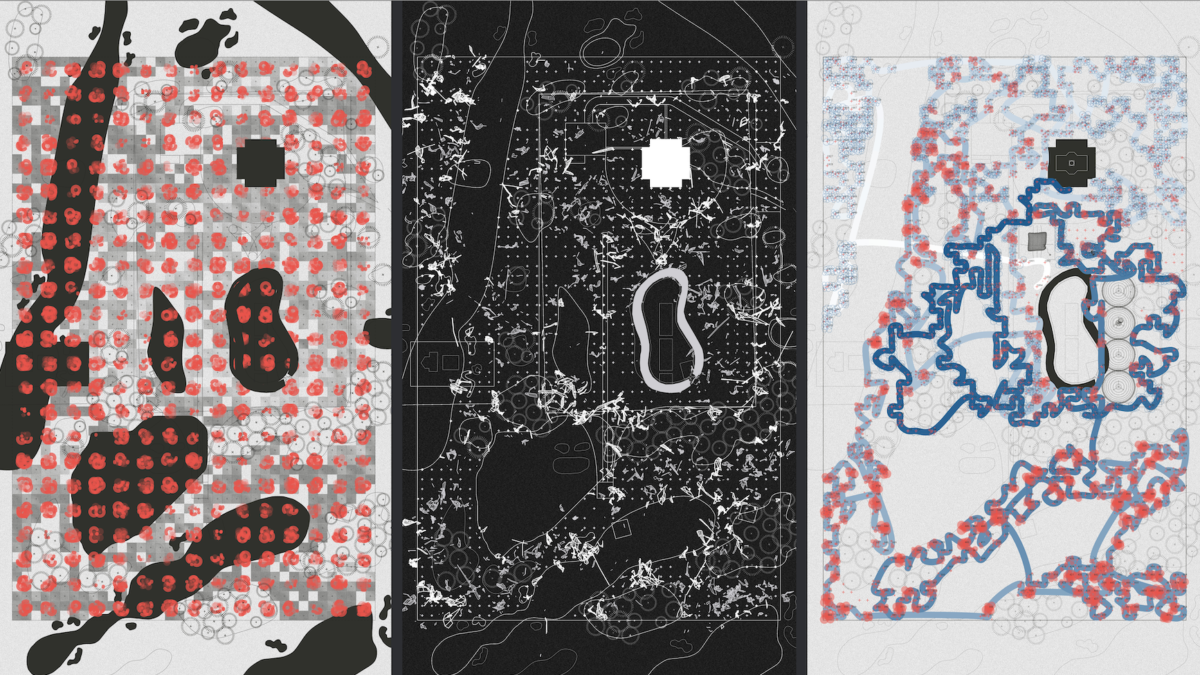

Responsive City

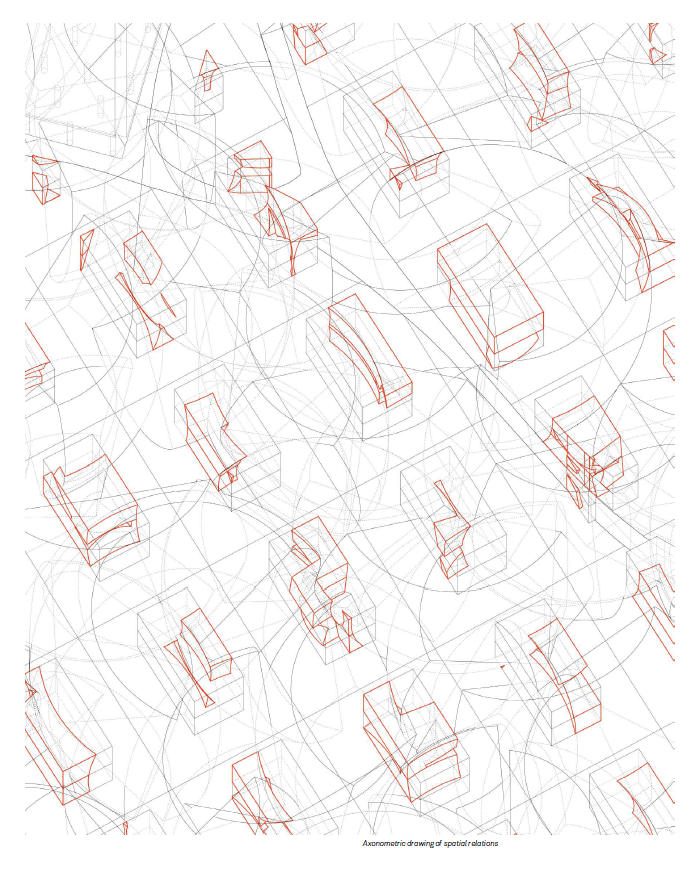

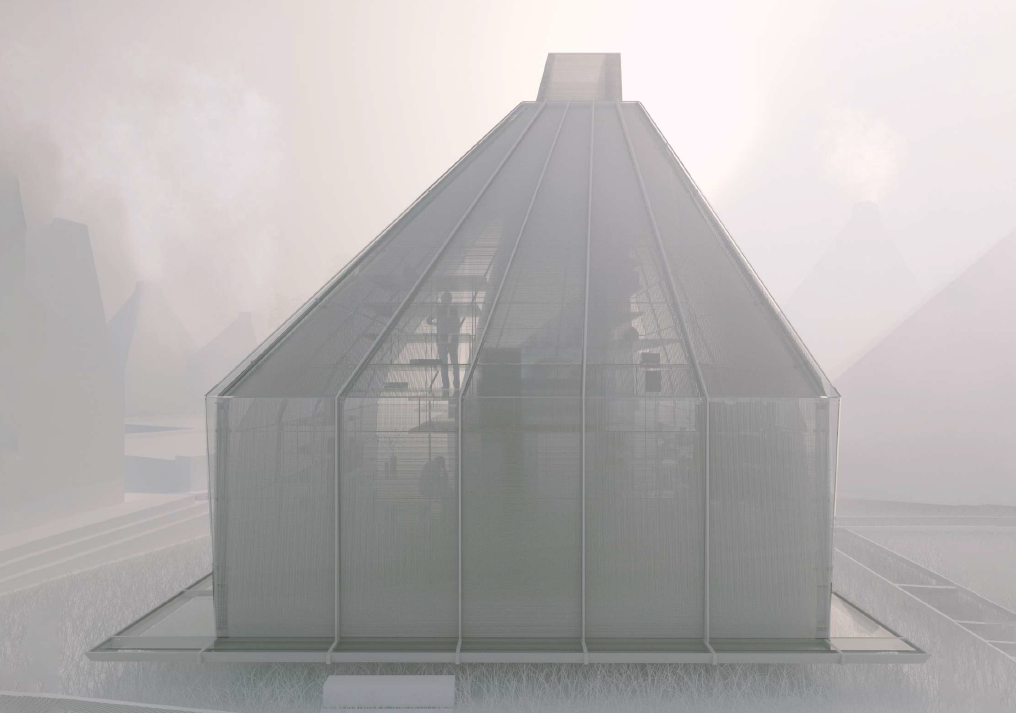

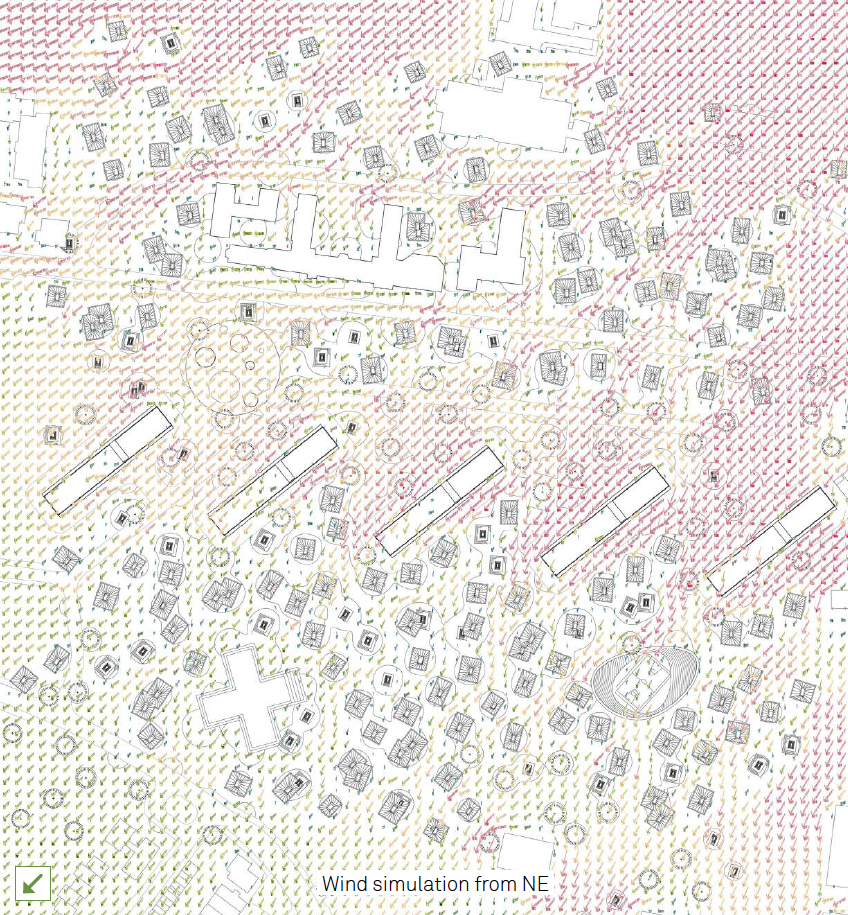

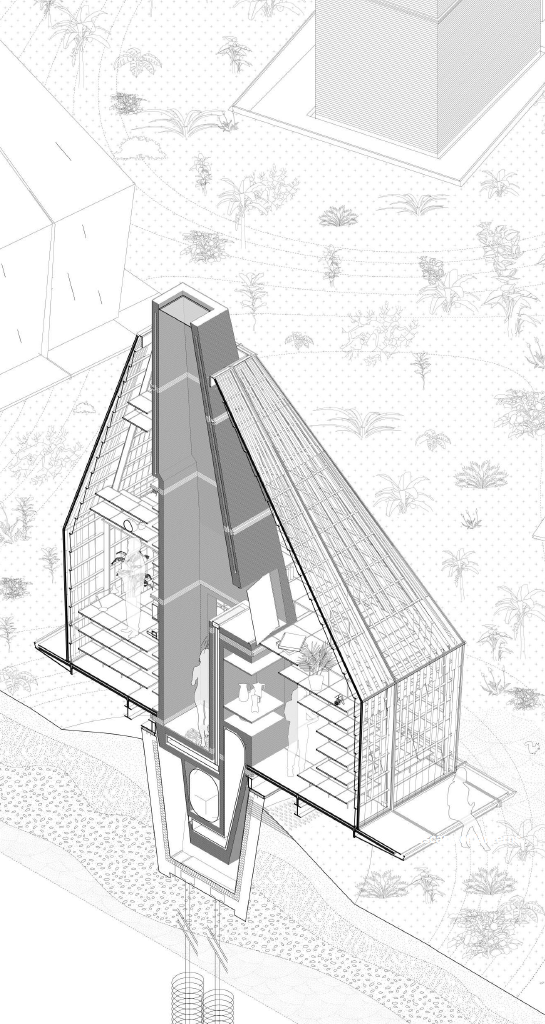

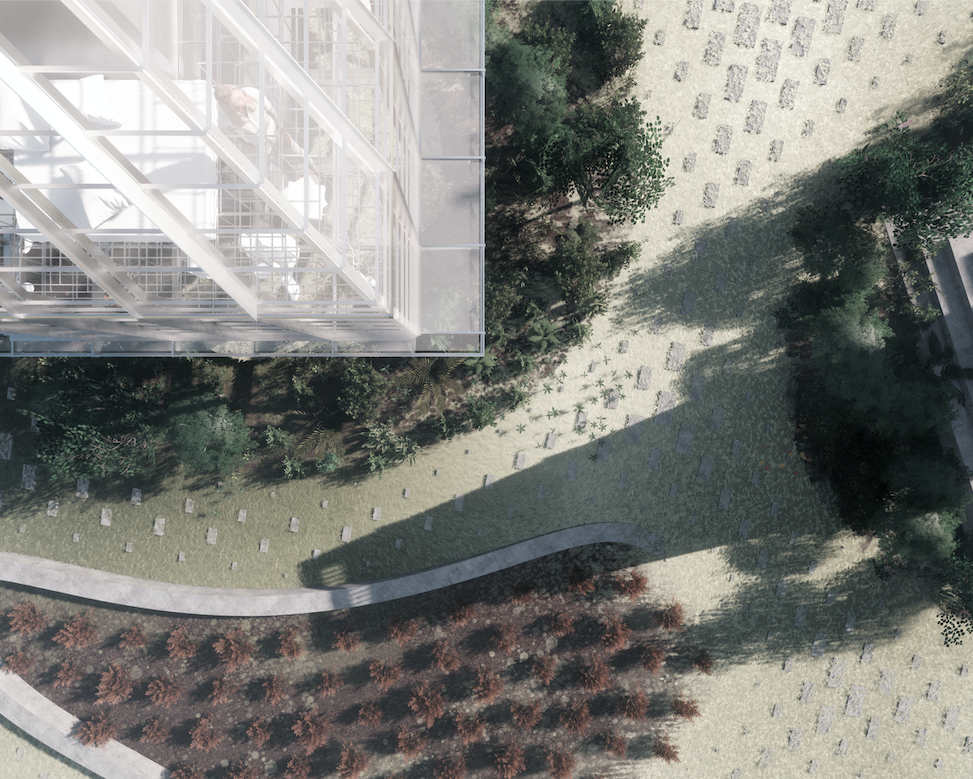

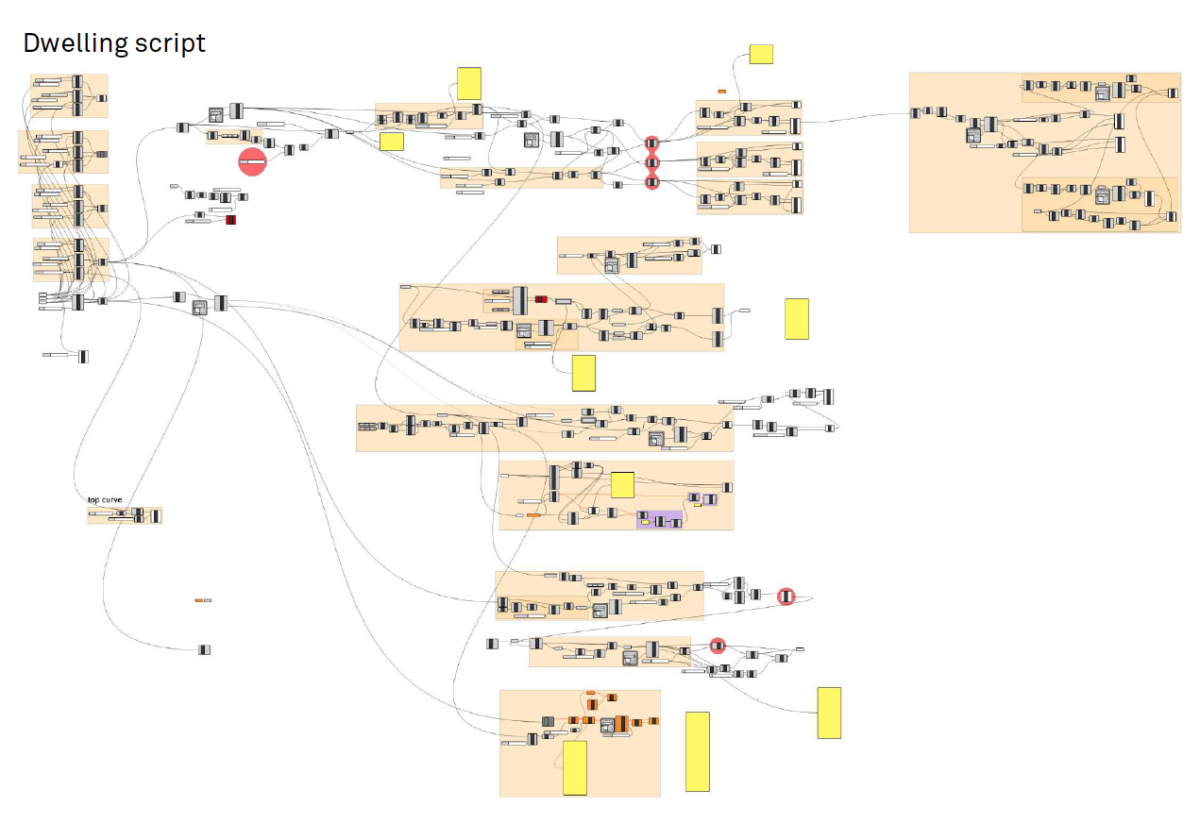

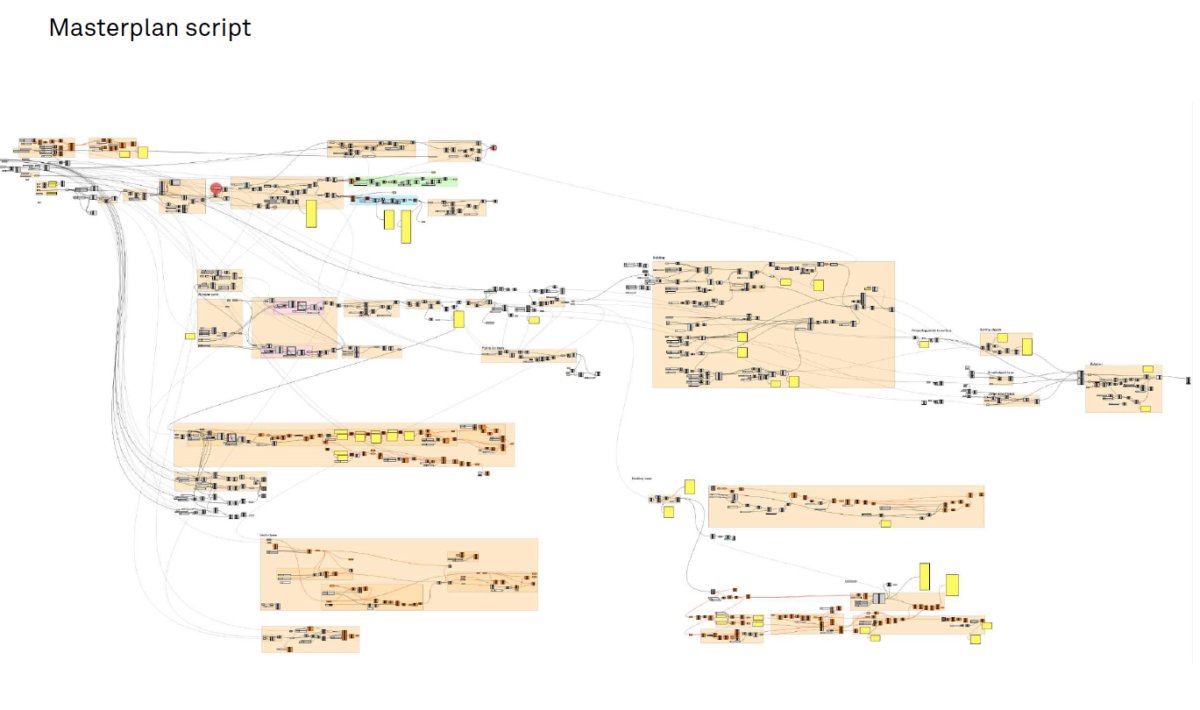

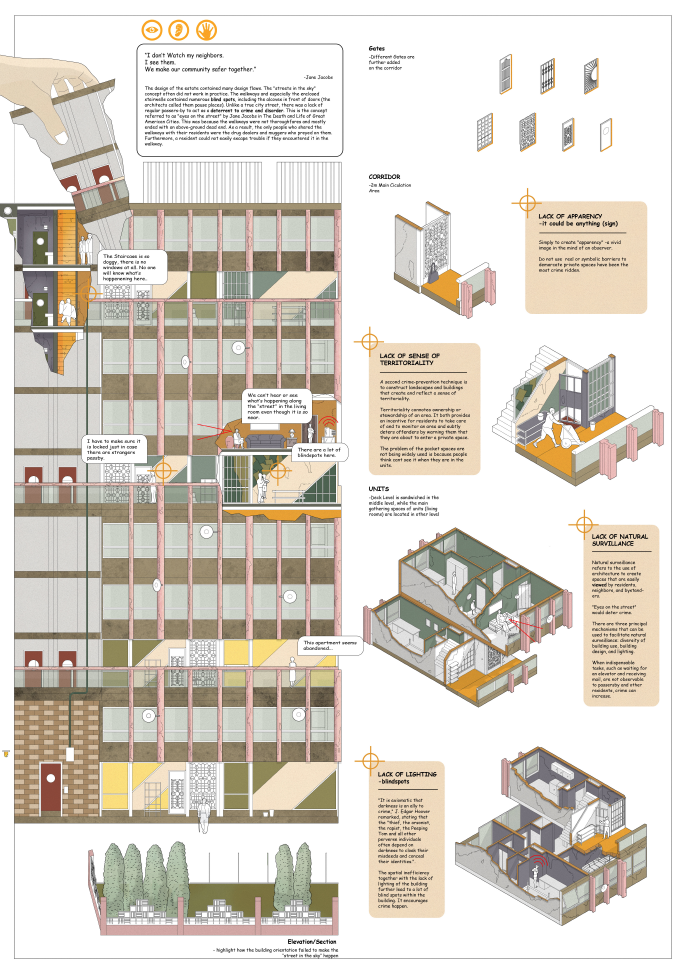

This project begins by considering how we can restock housing and densify society by exploring current building regulations. This project is particularly focused on the notion of overlooking. The “structure” of overlooking, that is both how overlooking can mean to provide a view of and to oversee (as in not seeing), are translated into regulations, social interactions and architecture.

The project is located around Alton Estate’s slab blocks which were built in the 1950’s and based on the utopian modernist ideals of Unite d’Habitation. Today, however, the Estate deals with a series of social problems.

The most unsettling of which is the way that the physical and mental aspects of life have been disconnected from their surroundings.

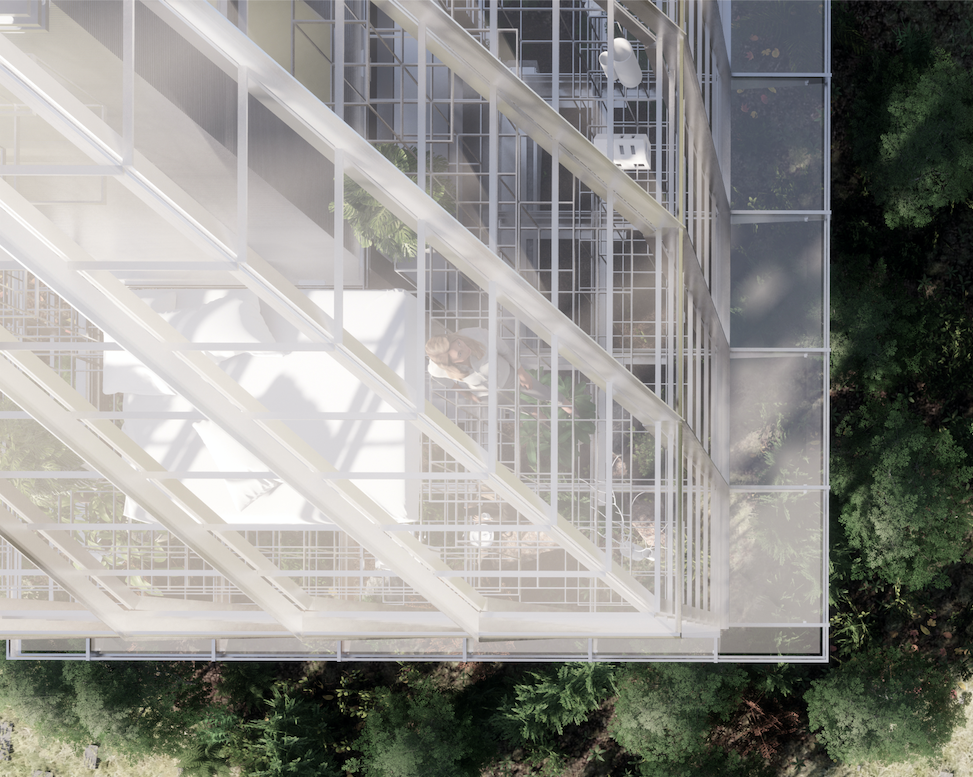

This project picks up on these problems and tries to deal with them through the concept of overlooking. As a result, the project creates an ecosystem of overlooking and a housing typology that stems from its immediate surroundings. This form of housing questions our understanding of public and private spaces as well as the individual and the community.

The project takes part of a larger regeneration plan for the Alton Estate and restocks the Estate with 225 new dwellings. The following document jumps between scales, moving between the bird’s-eye view of the entire development to zooming in on one house. This project investigates how inhabiting a single household to directly relates to the household’s surroundings and how this reflects back on the entire community.

As part of developing this scheme, this project investigates what it means to live in transparency as the dwellings are mainly constructed of glass. By utilizing glass, this project investigates how glass responds to social and environmental conditions.

Does considering “overlooking” in all stages of the process create stronger bonds between the inhabitants and help build a stronger community? And does it help nurture an environment which is more responsive to both social, economic and environmental changes?