Category: Featured

Featured projects from across the years

(RE) Placing the Urban Hanok

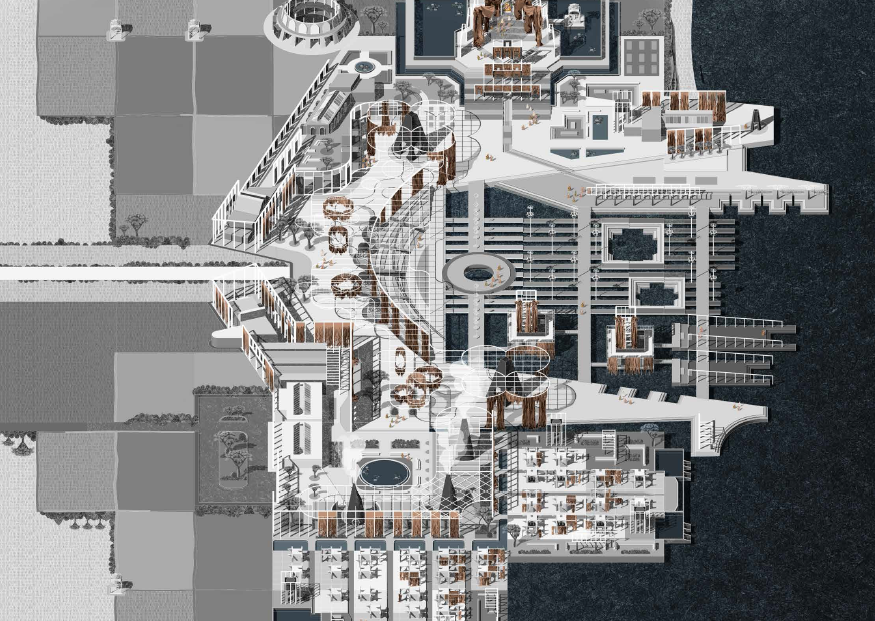

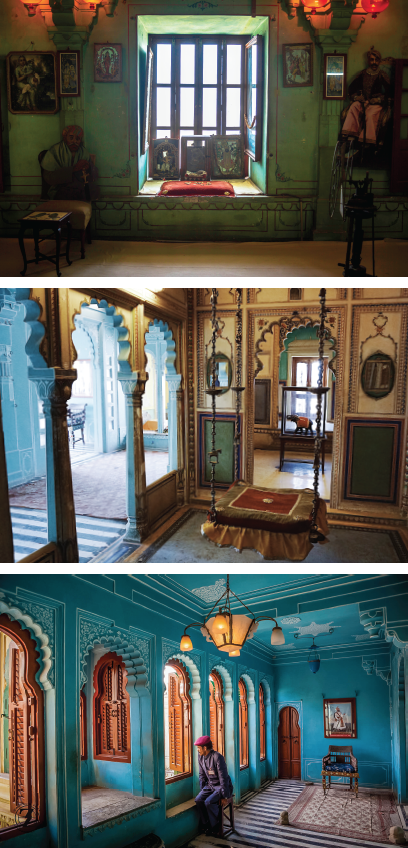

This project sets out to question the position of historic housing stock within cities which have rapidly developed since its original construction. It highlights a current global phenomenon that residential areas of historic value, which are often located in premium locations in developed cities, have become expensive, tourist-orientated neighbourhoods. Focusing on Seoul’s historic urban courtyard typology and the context in which it emerged in the 1930s, as well as the current environment in which it exists, the project discusses how contextual change results in a changed relevance of historic housing.

Focusing on Seoul’s remaining urban hanok neighbourhoods, the project investigates preservation strategies that have resulted in the majority of the city’s historic housing stock being rebuilt. The project employs Eunpyeong Hanok Village as a case study to investigate the Seoul Metropolitan Governments method of constructing entirely new urban hanok villages as a way of preserving the housing typology.

The project attempts to re-evaluate recognised approaches for urban development and preservation. It highlights a current tendency of urban preservation strategies resulting in the creation of exclusive and expensive contemporary neighbourhoods. It raises a question at a global scale of whether there is an alternative approach, where historic housing can be adapted in order to benefit local communities, and used as a site for additional affordable housing.

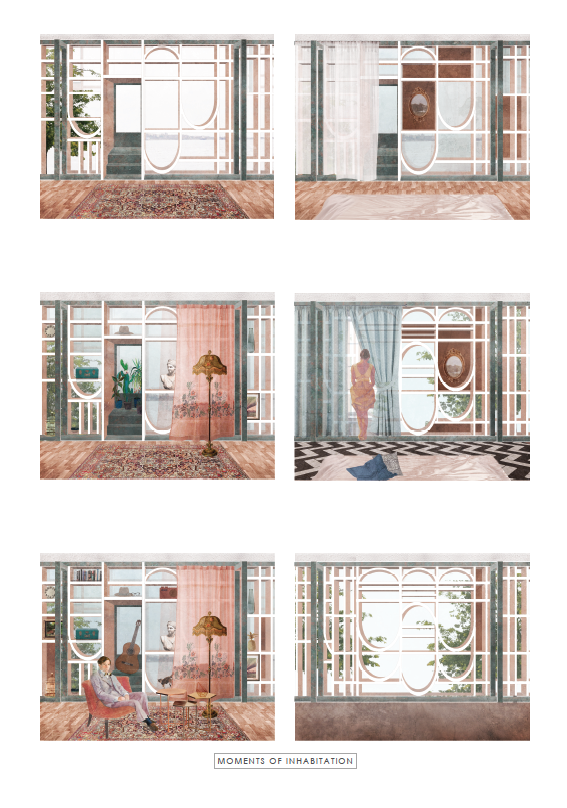

The project rejects theories on preservation which emphasise material originality and replicating aesthetic appearance. Instead, it focuses on the importance of preserving the social qualities and ideas on domestic space embedded within housing. It identifies the city as a fluid system which is continually and incrementally changing. Historic housing stock should therefore be allowed to adapt and change to different contexts and new generations of inhabitants.

As shown in Seoul, rapid urban development can force a city to re-evaluate its historic housing stock. Surrounded by newer, taller and modernised developments, historic housing stock can appear outdated.

If historic housing stock is not reinvented within new contexts, it risks becoming irrelevant. It may be demolished and replaced with something new – as with the urban hanoks over the past 50 years – or preserved and converted into an exclusive typology, beneficial for tourism or a privileged few.

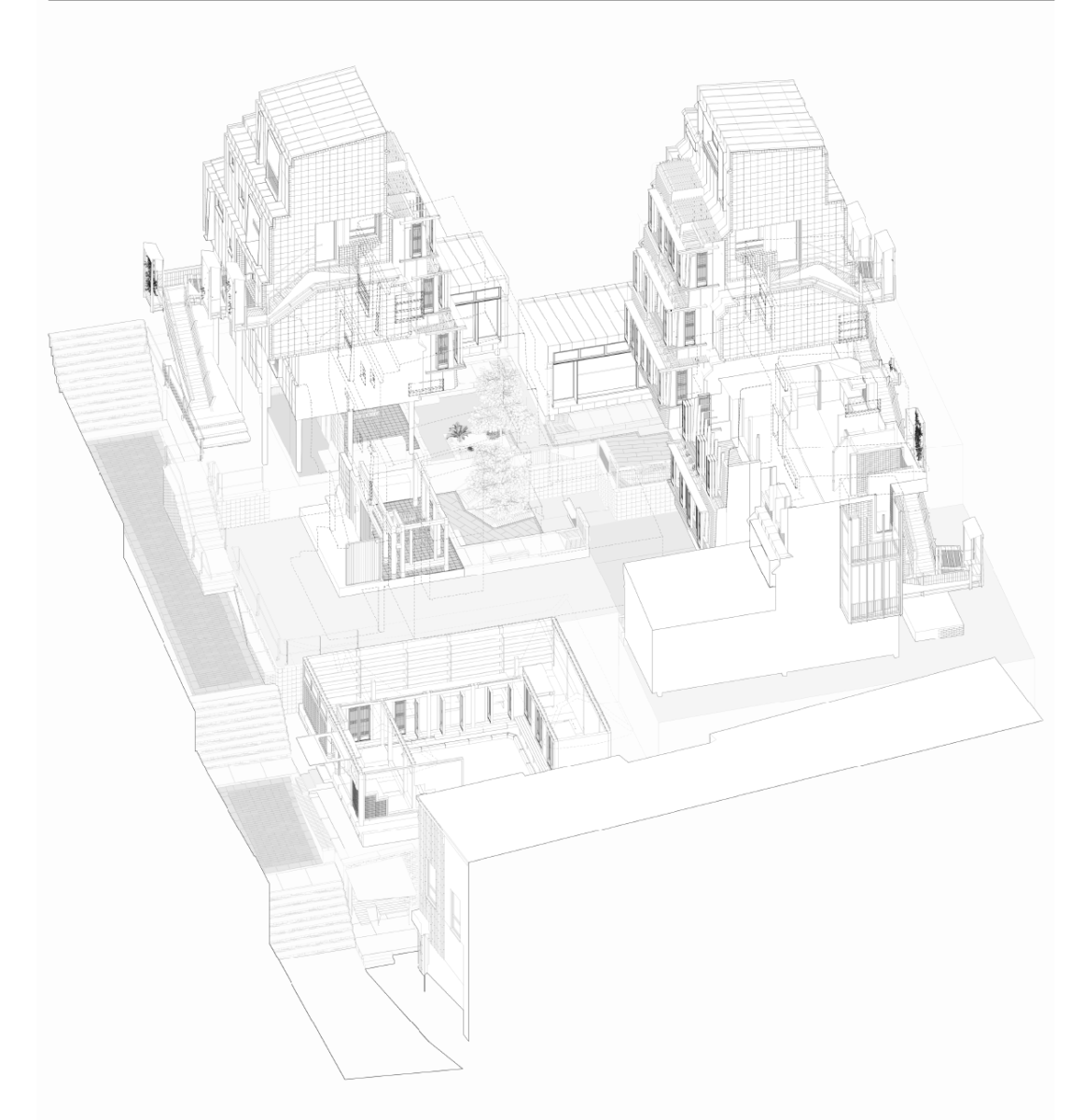

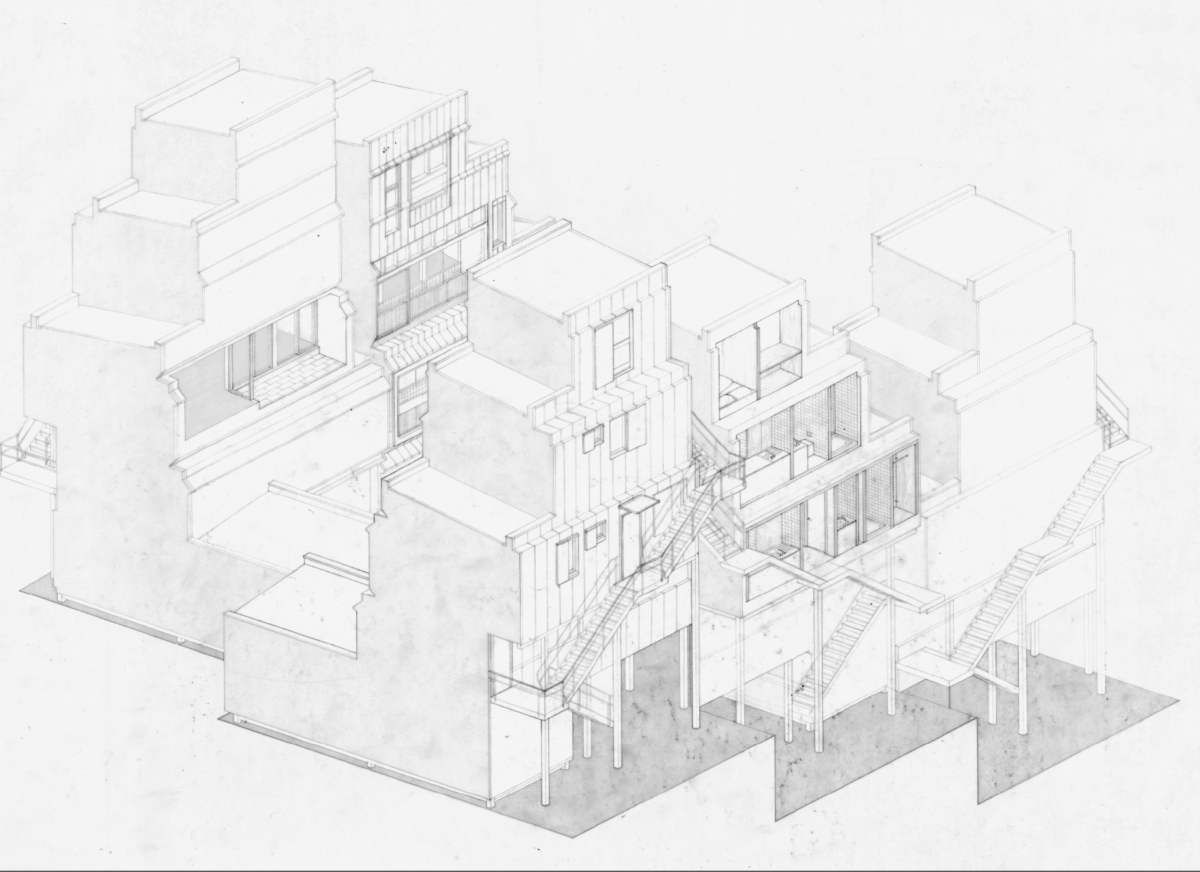

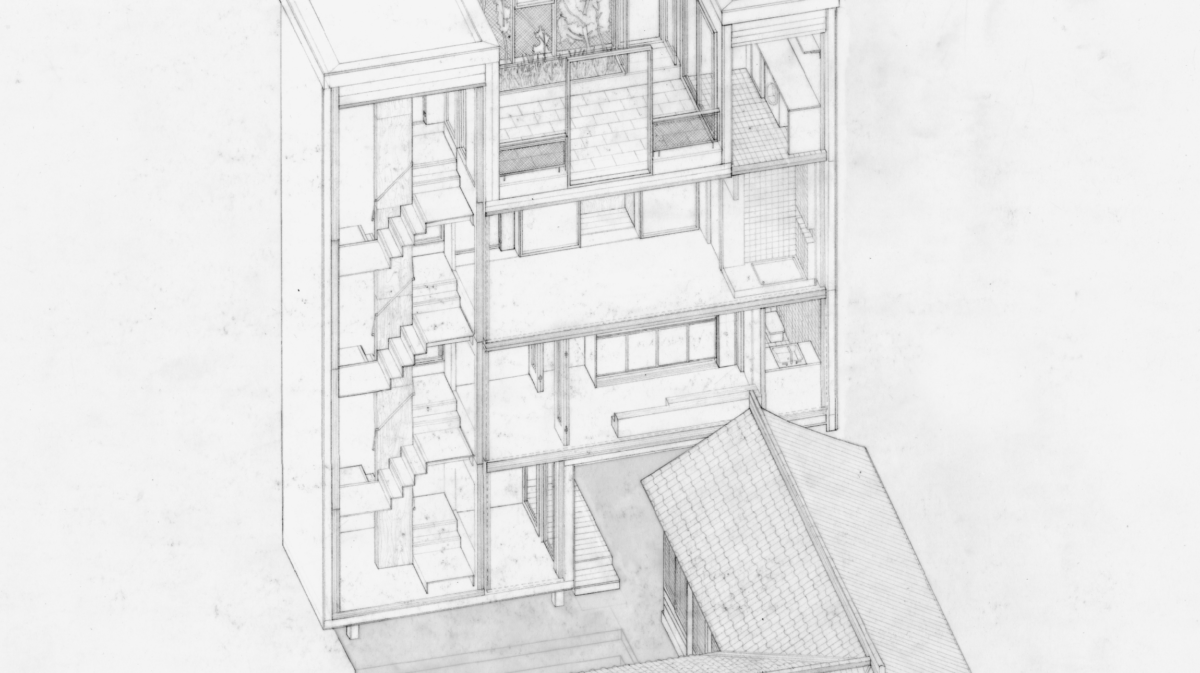

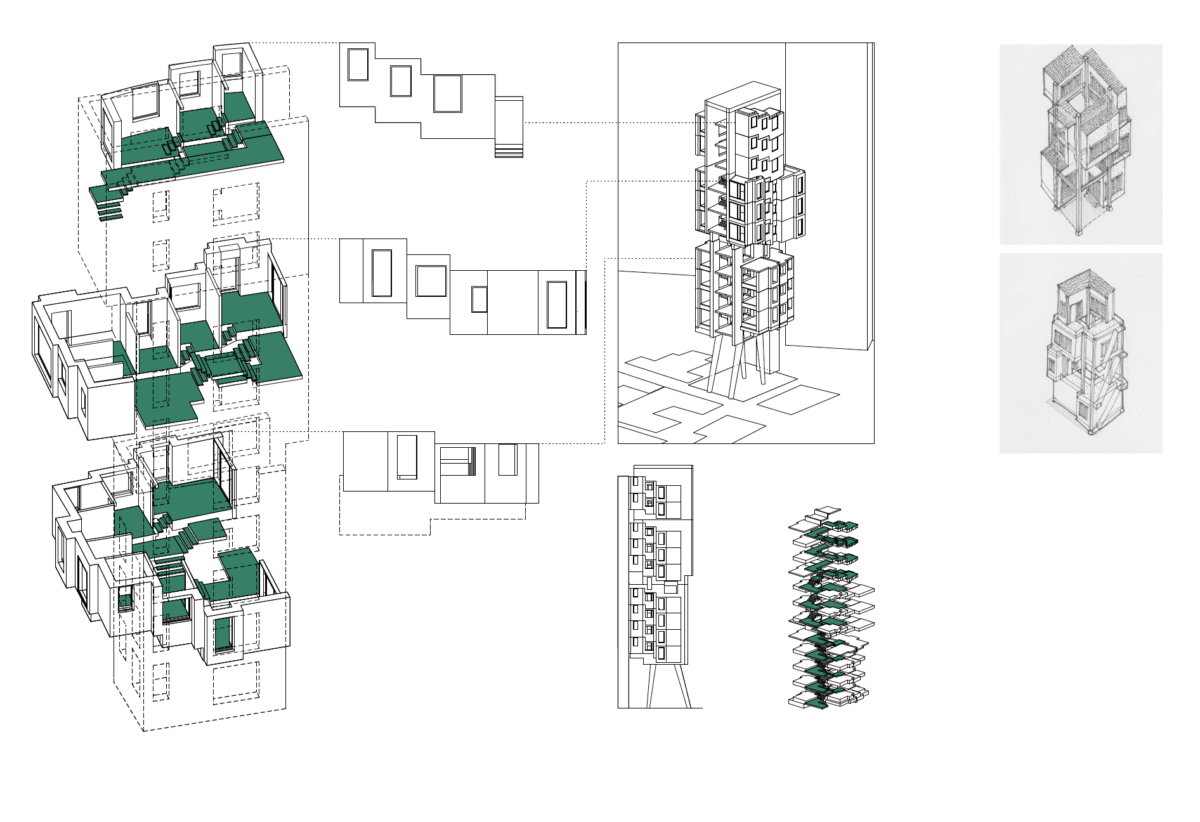

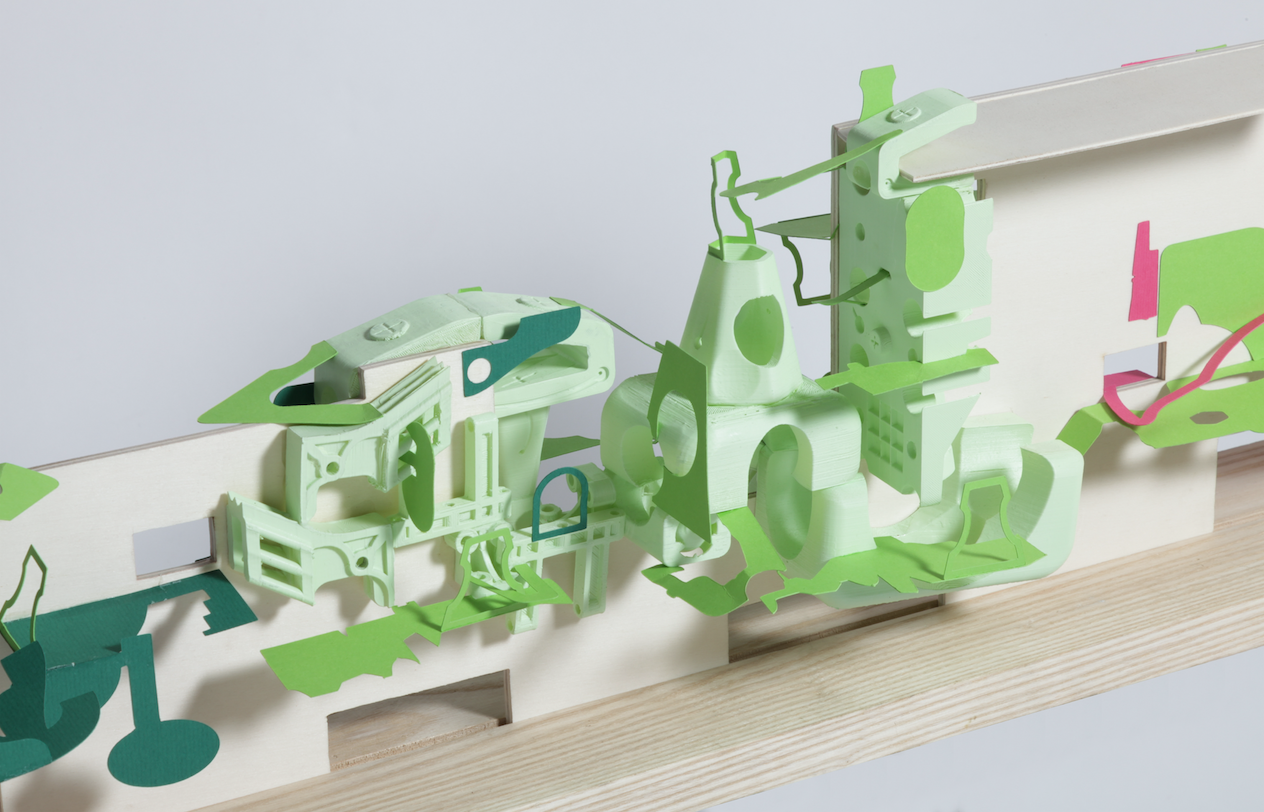

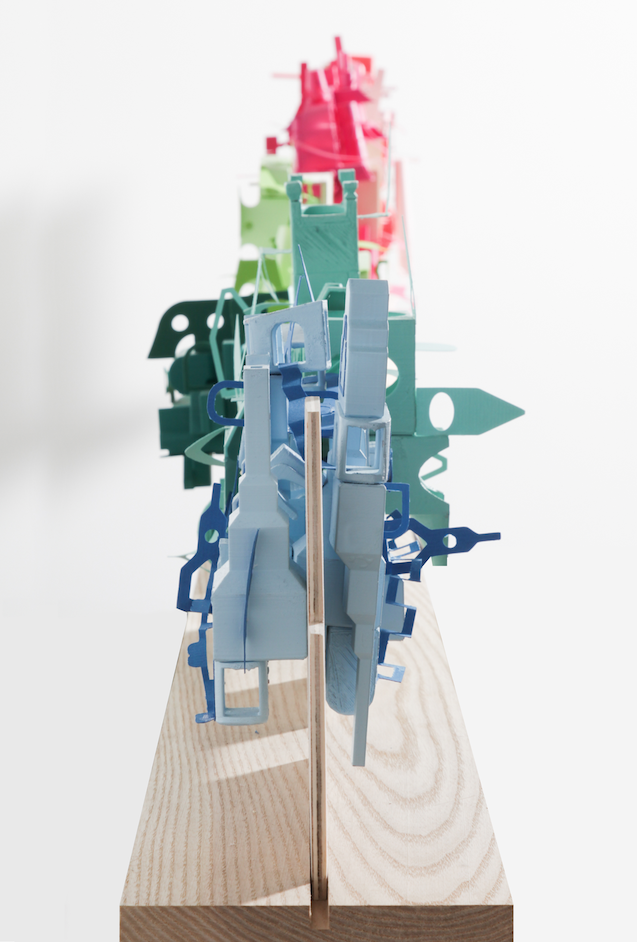

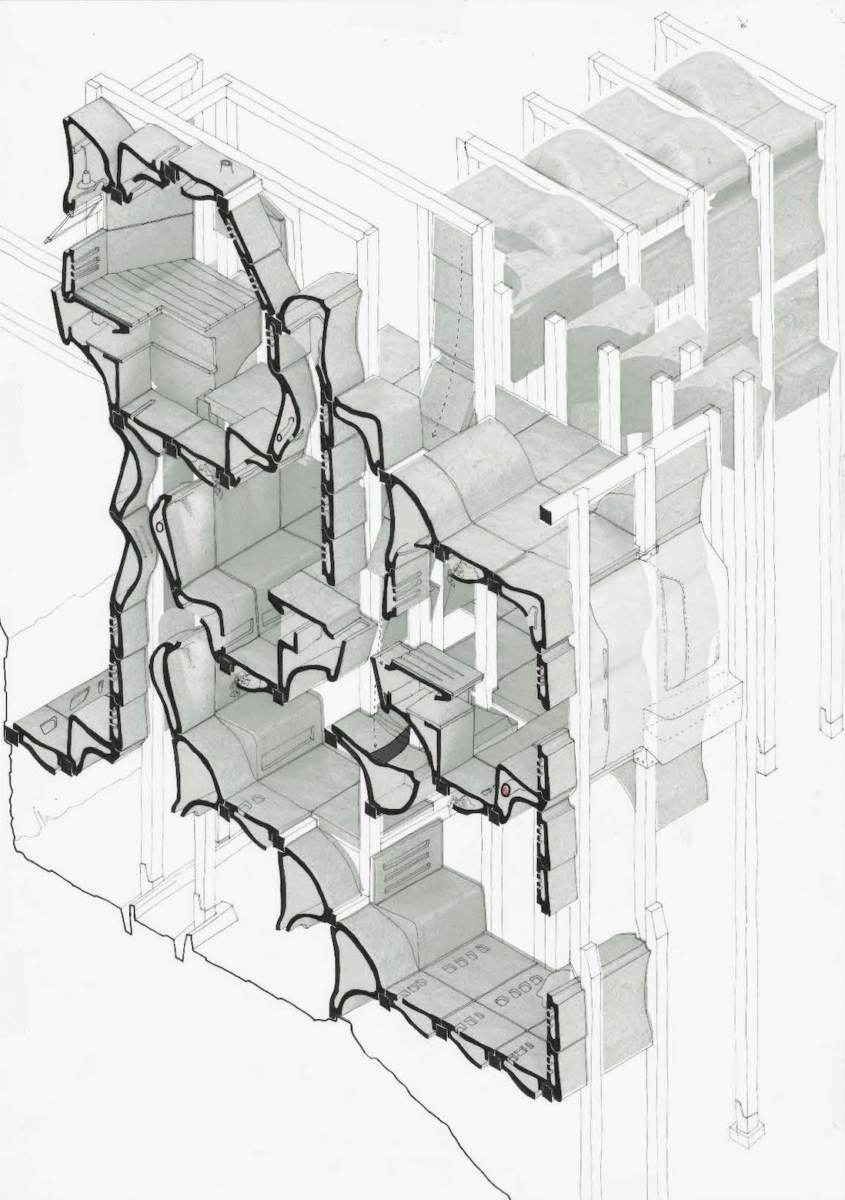

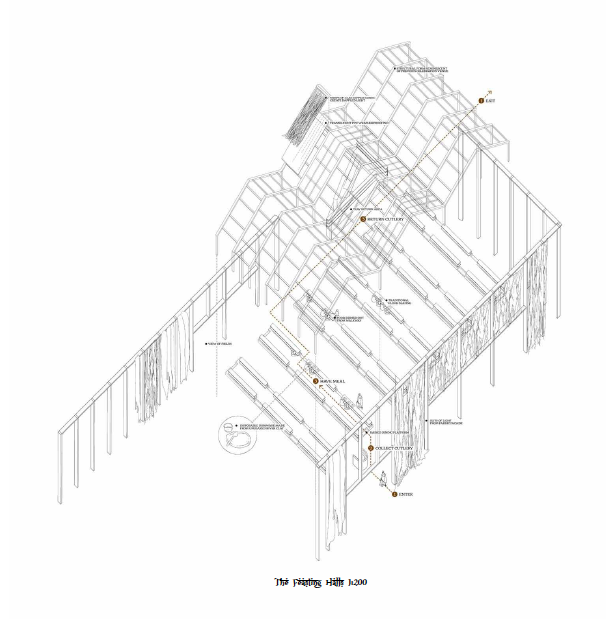

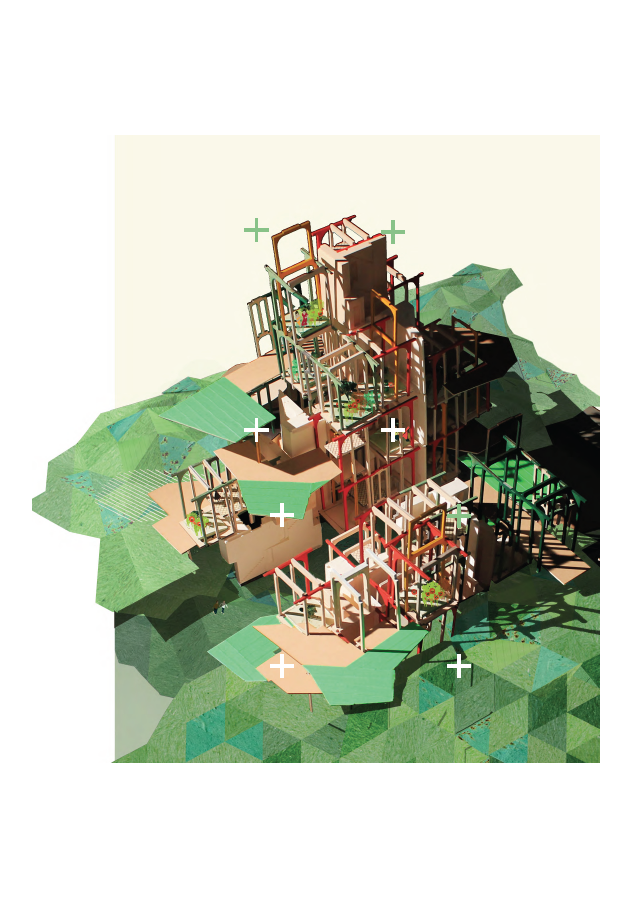

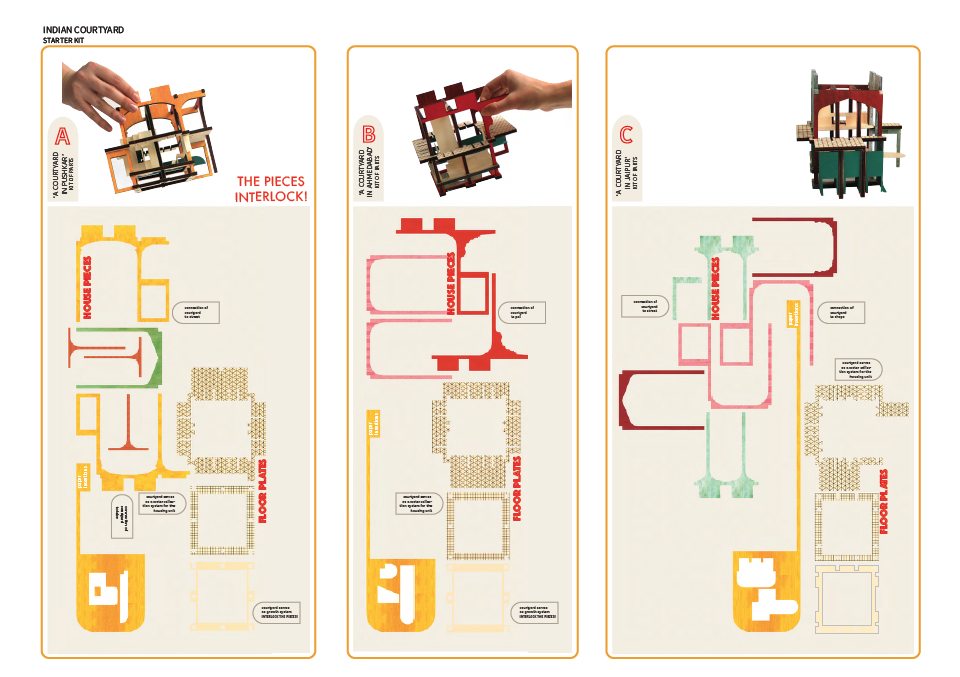

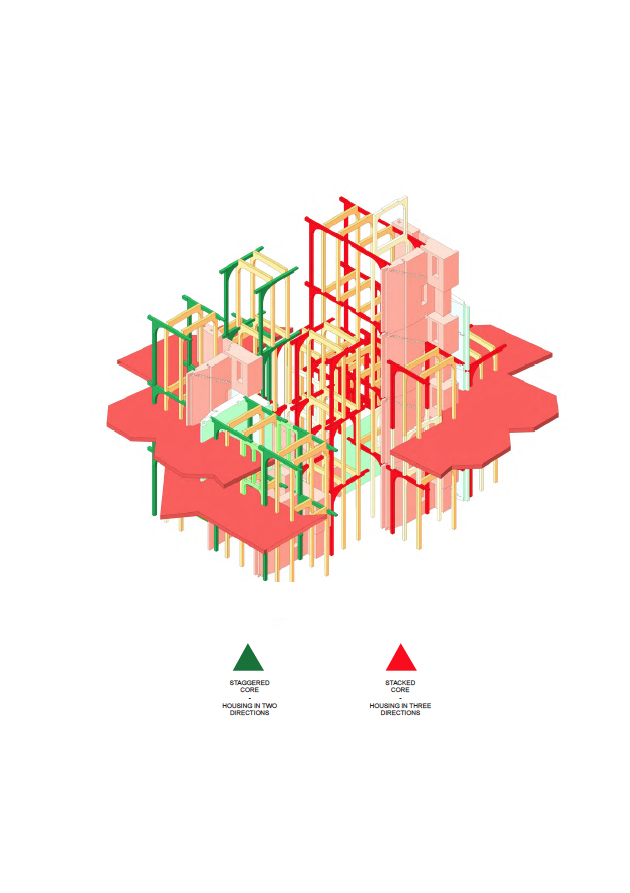

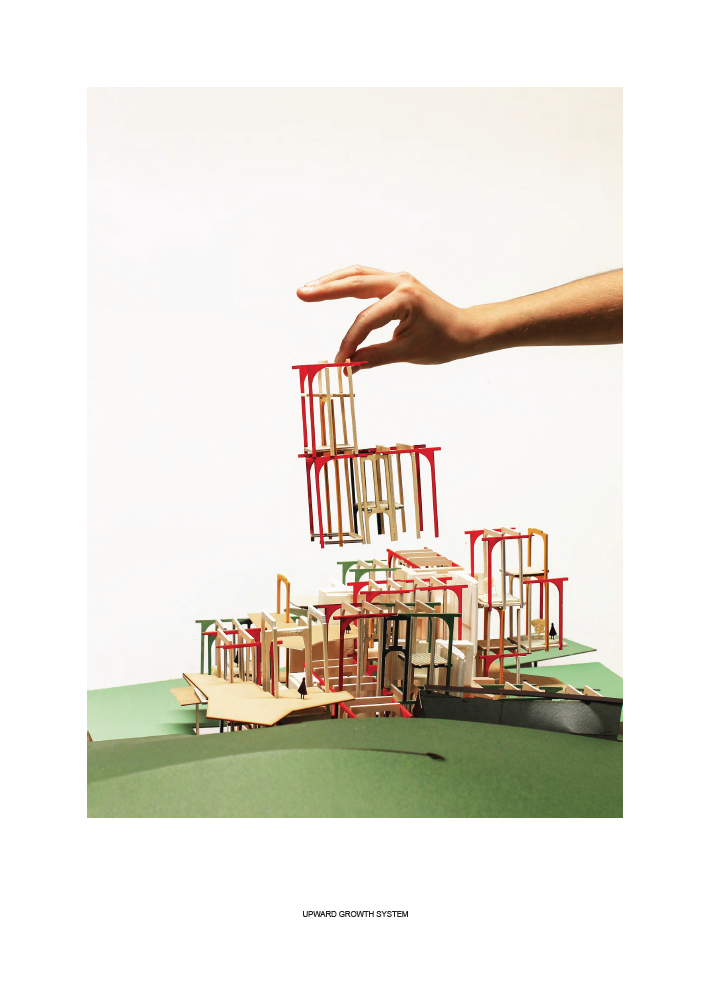

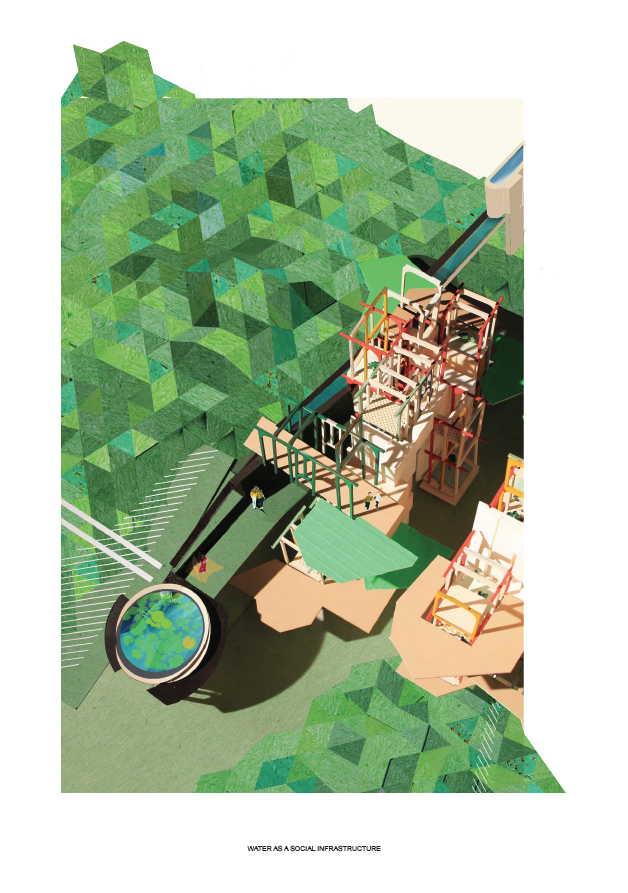

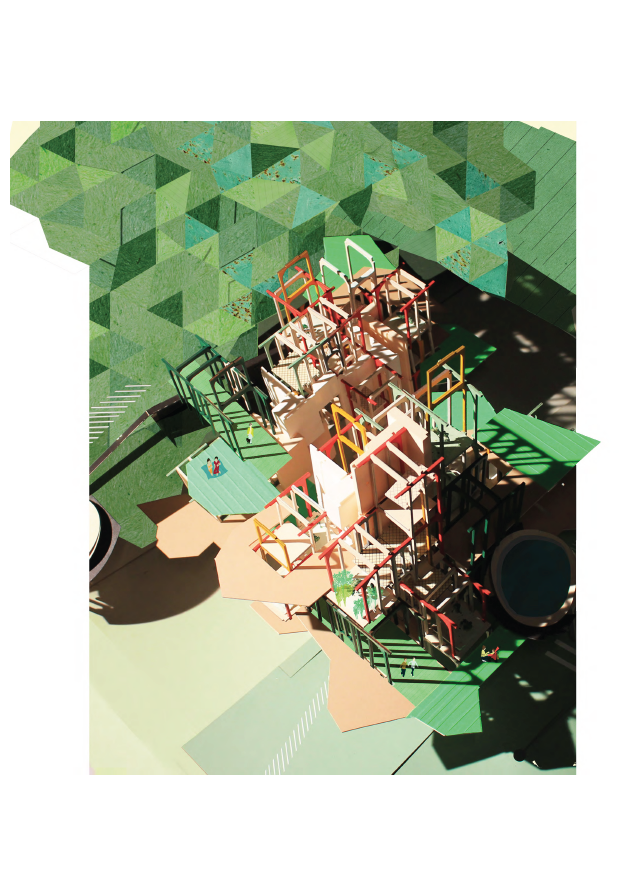

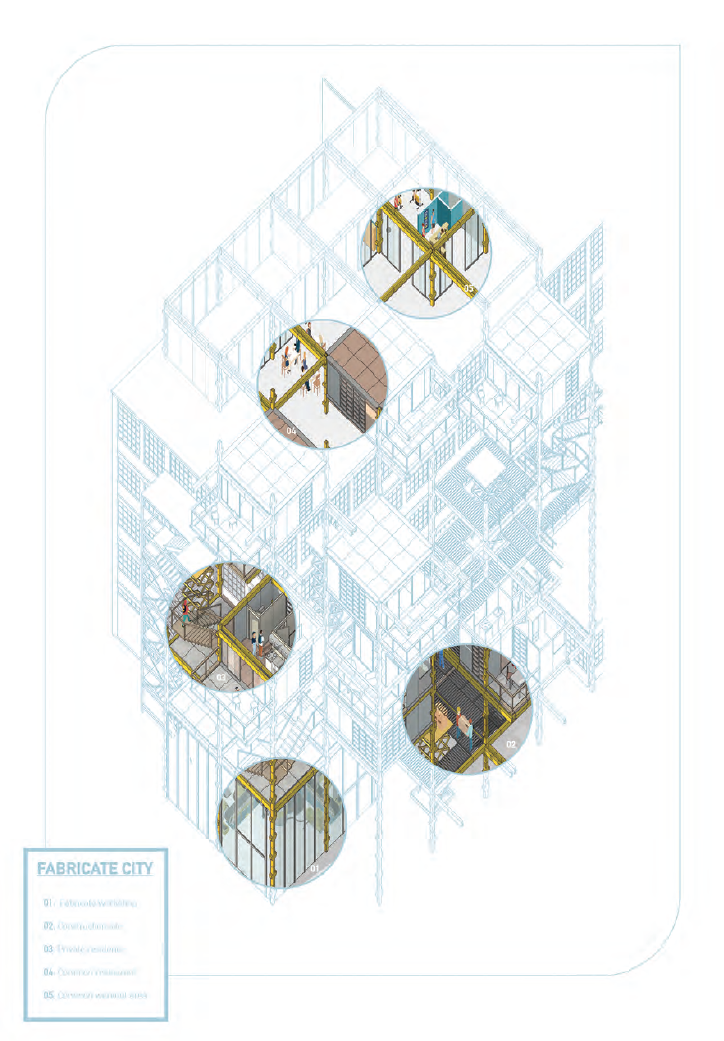

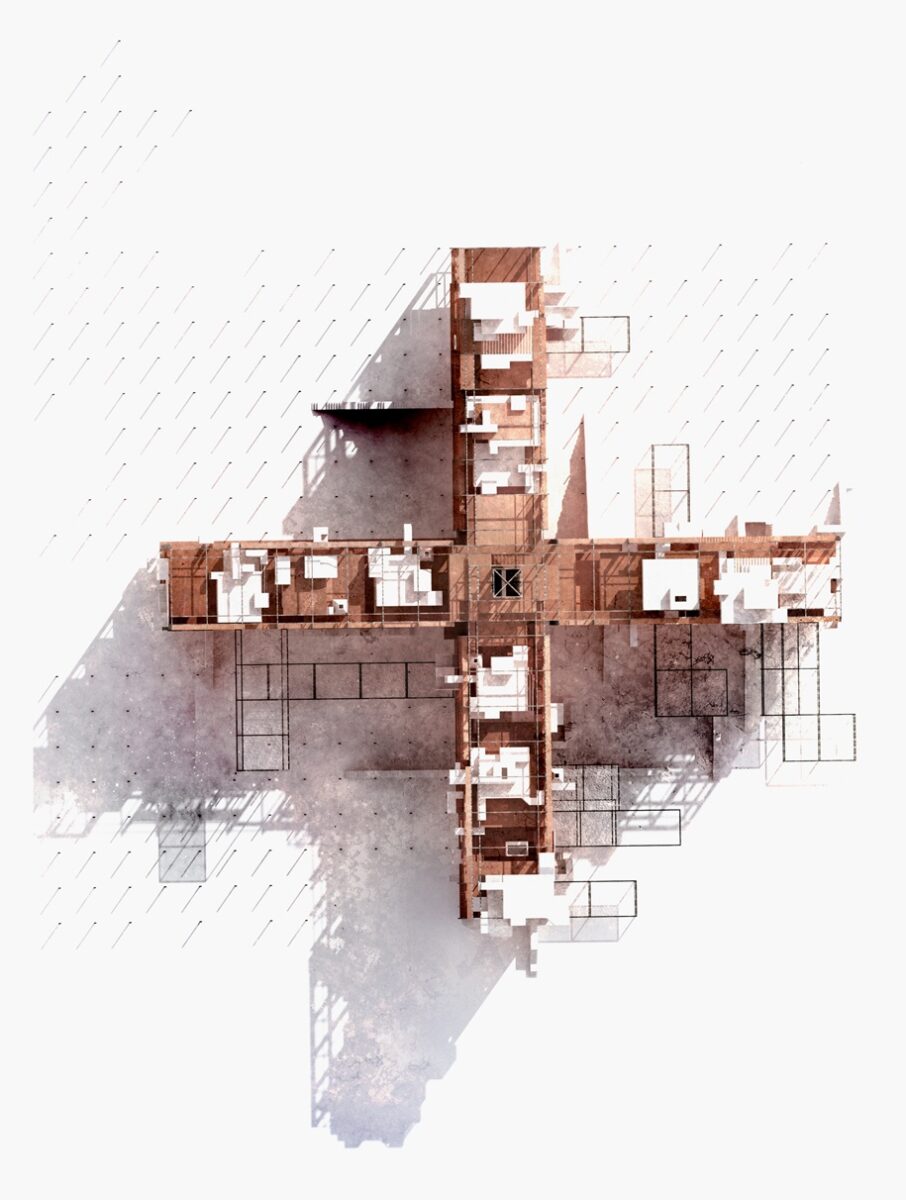

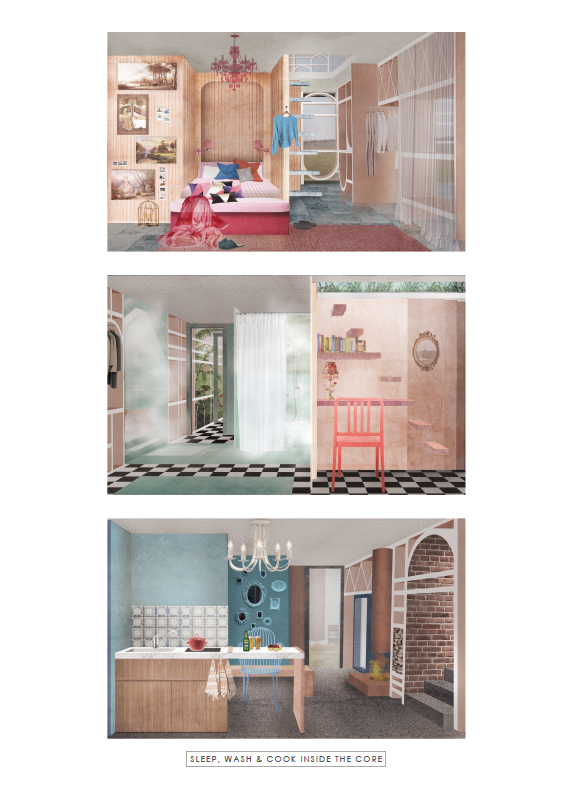

The project speculates on how housing design can be allowed to evolve. It does this by studying the existing condition of the urban hanok is terms of its structural and spatial design as well how it has been adapted and appropriated by residents. The design then provides a higher density typology which introduces contemporary construction methods and ideas on inhabitation, while retaining a layout influenced by the original urban hanok form.

The design provides an example of a reinvented typology that responds to the contextual needs of the present day. It also demonstrates how housing can be additively changed on a plot-by-plot basis. It opposes both a broad master-planned re-development of an area, or preserving a neighbourhood as a whole.

Sewoon Sanga Pig Farm, Seoul, South Korea

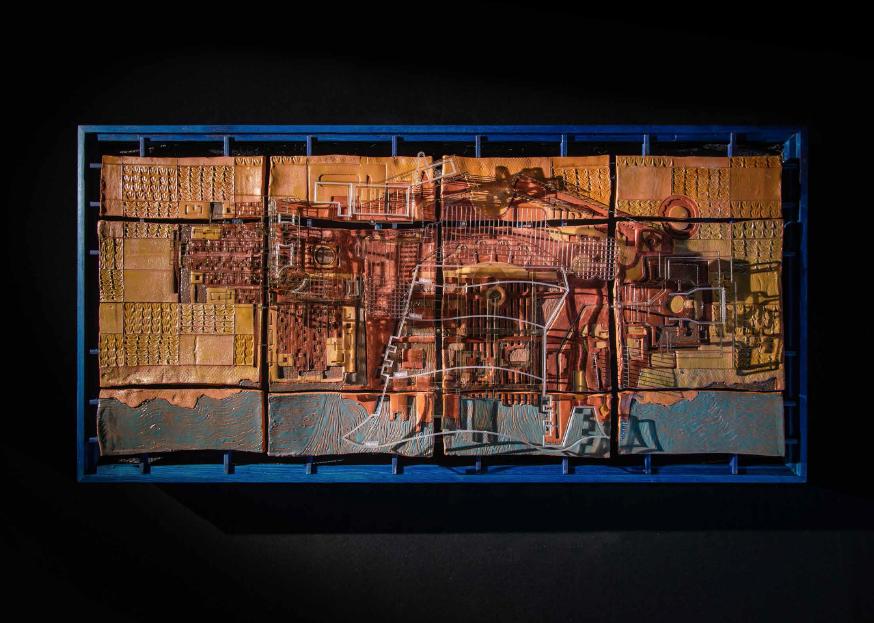

Ceramic House Seoul

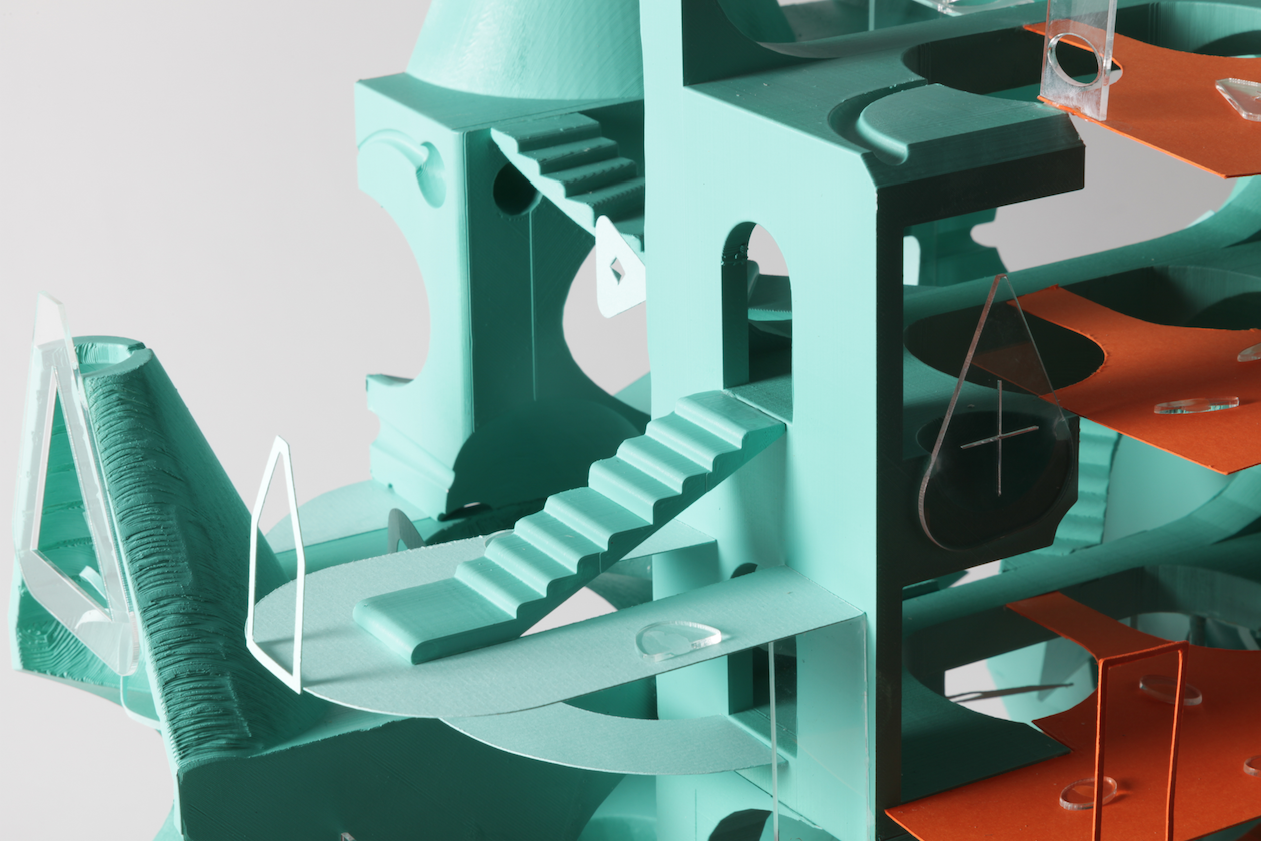

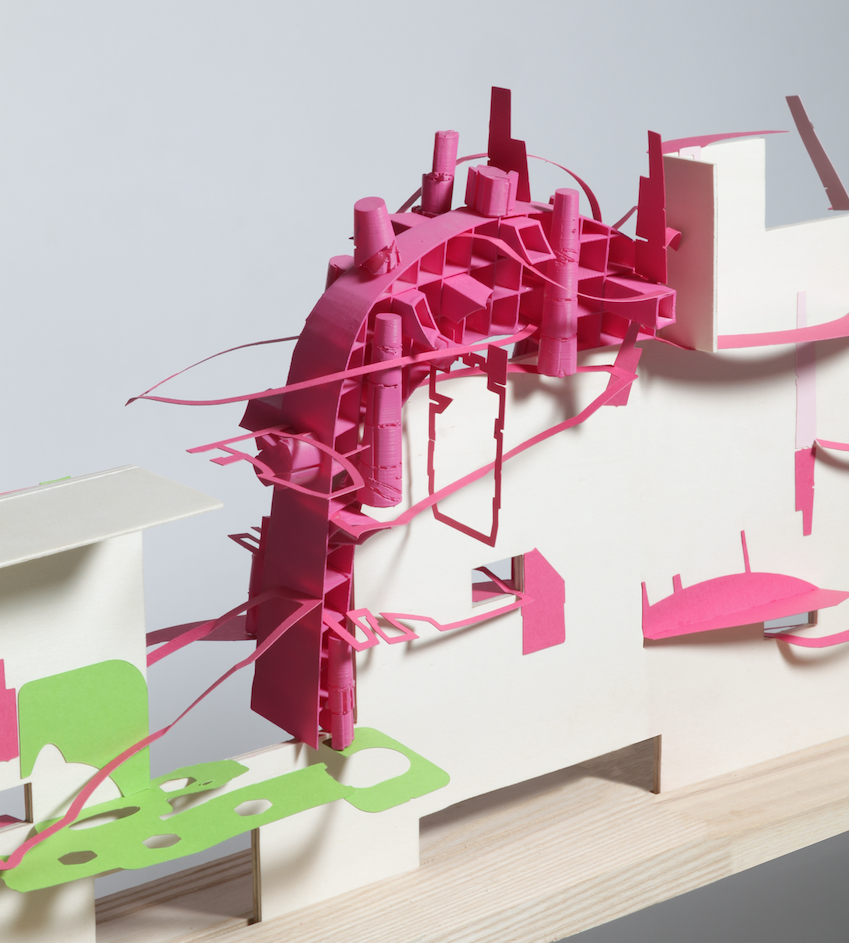

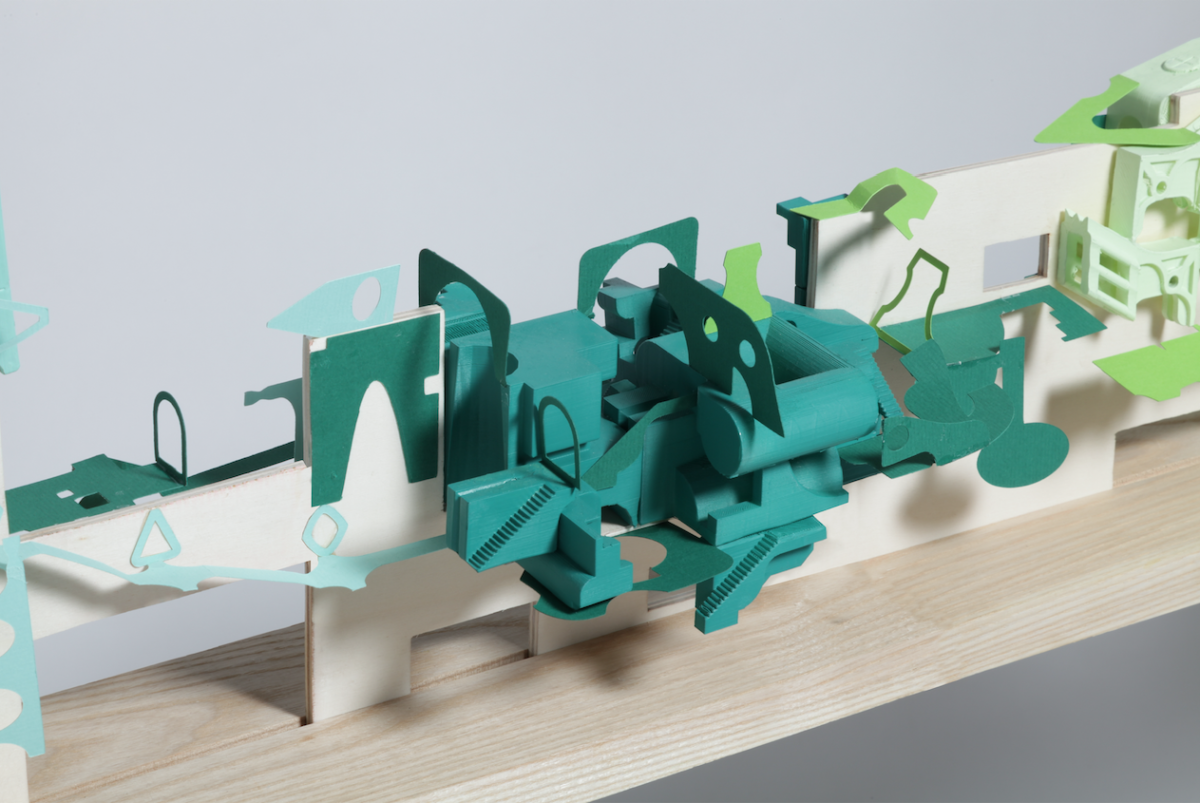

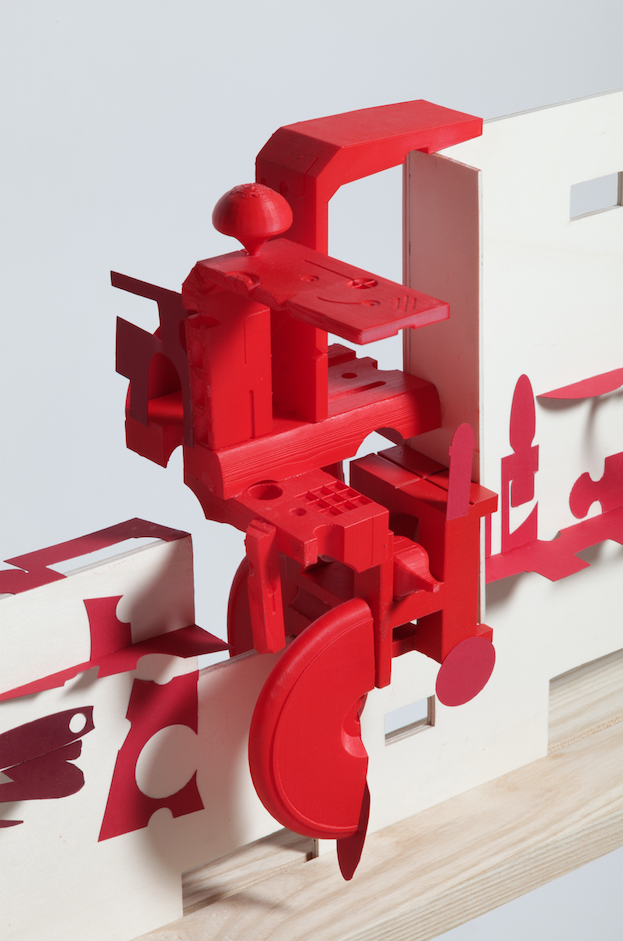

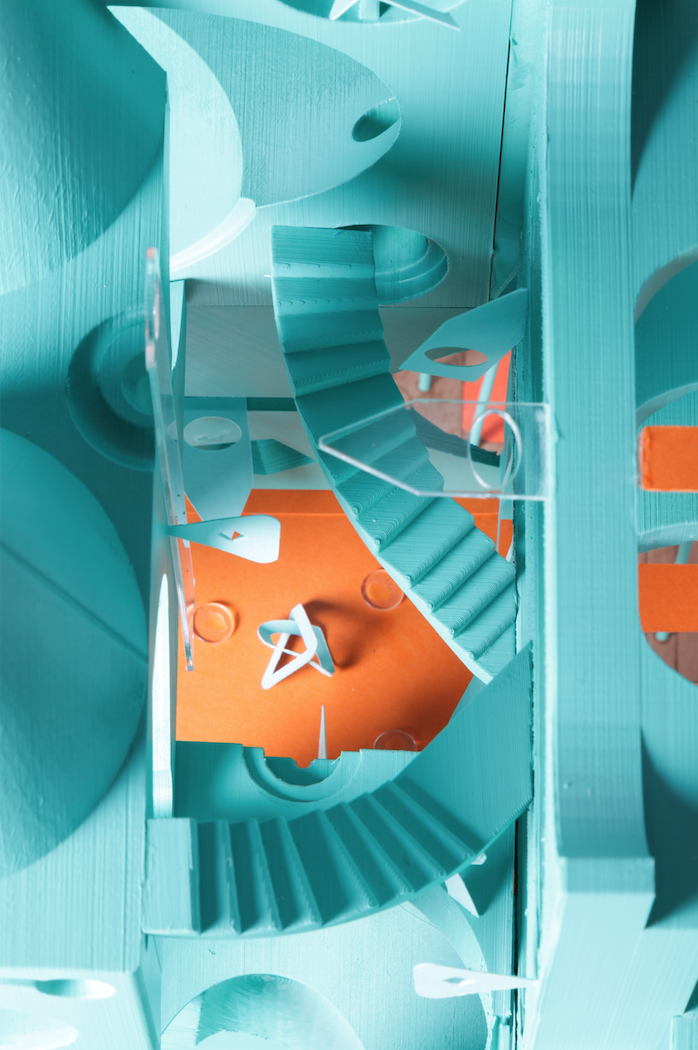

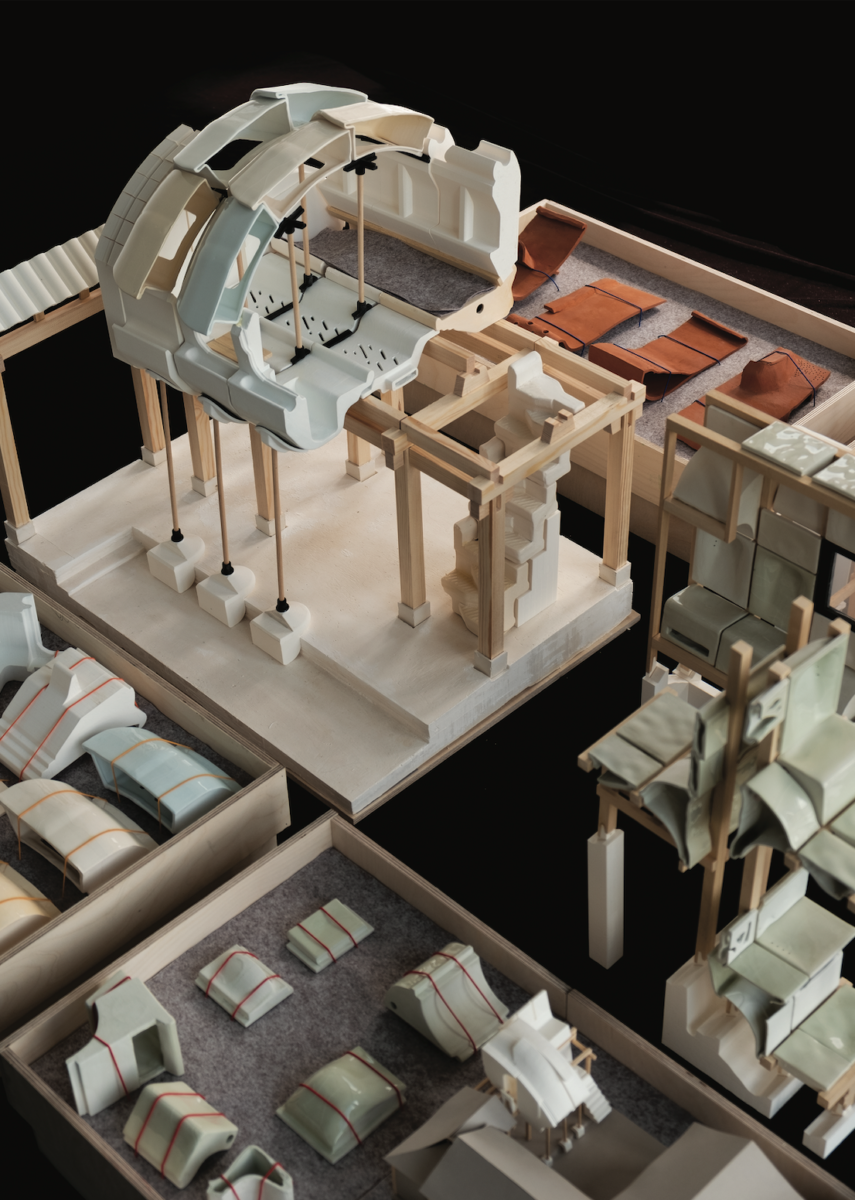

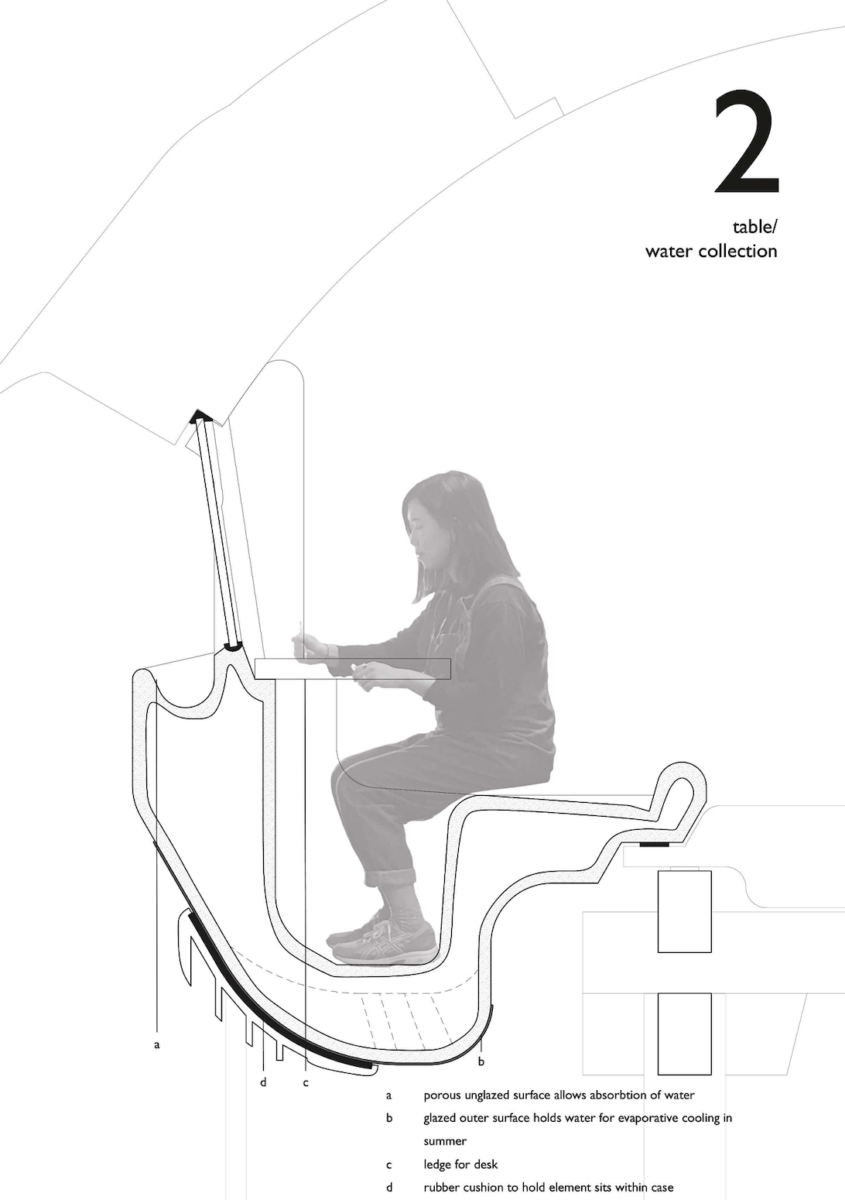

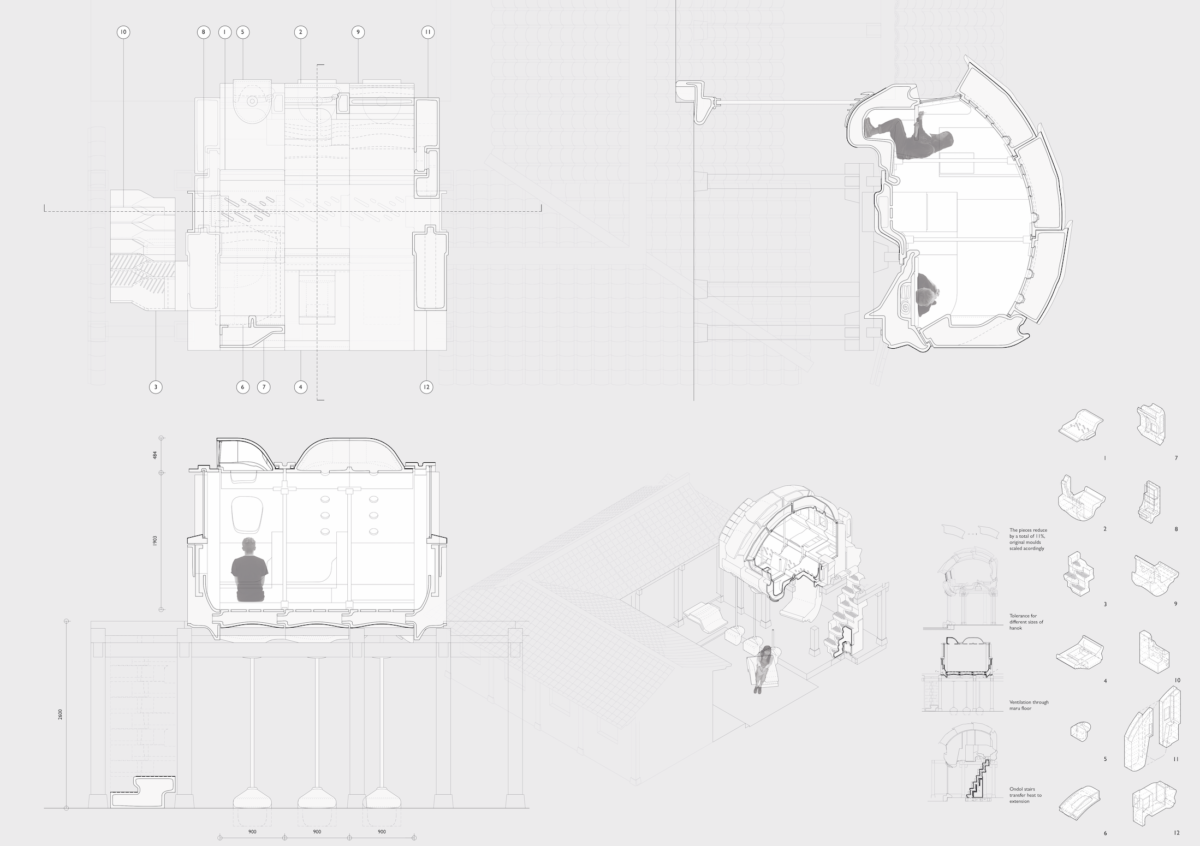

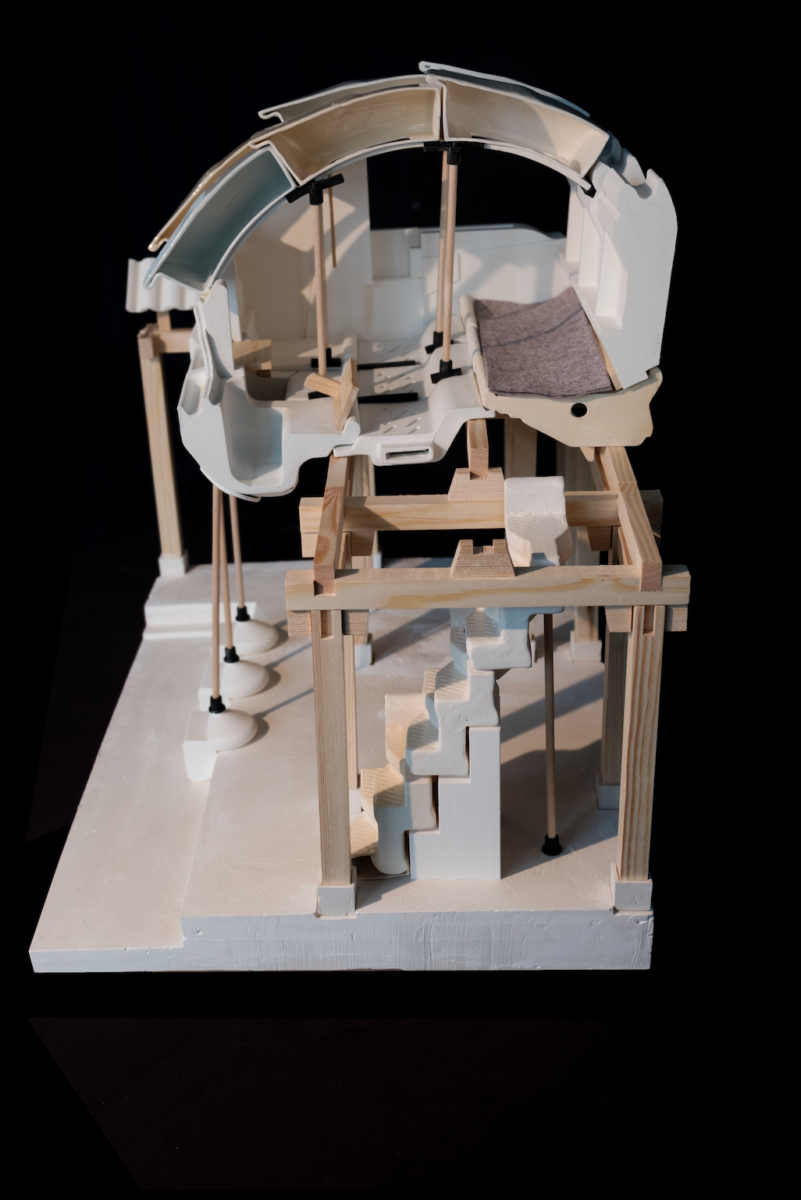

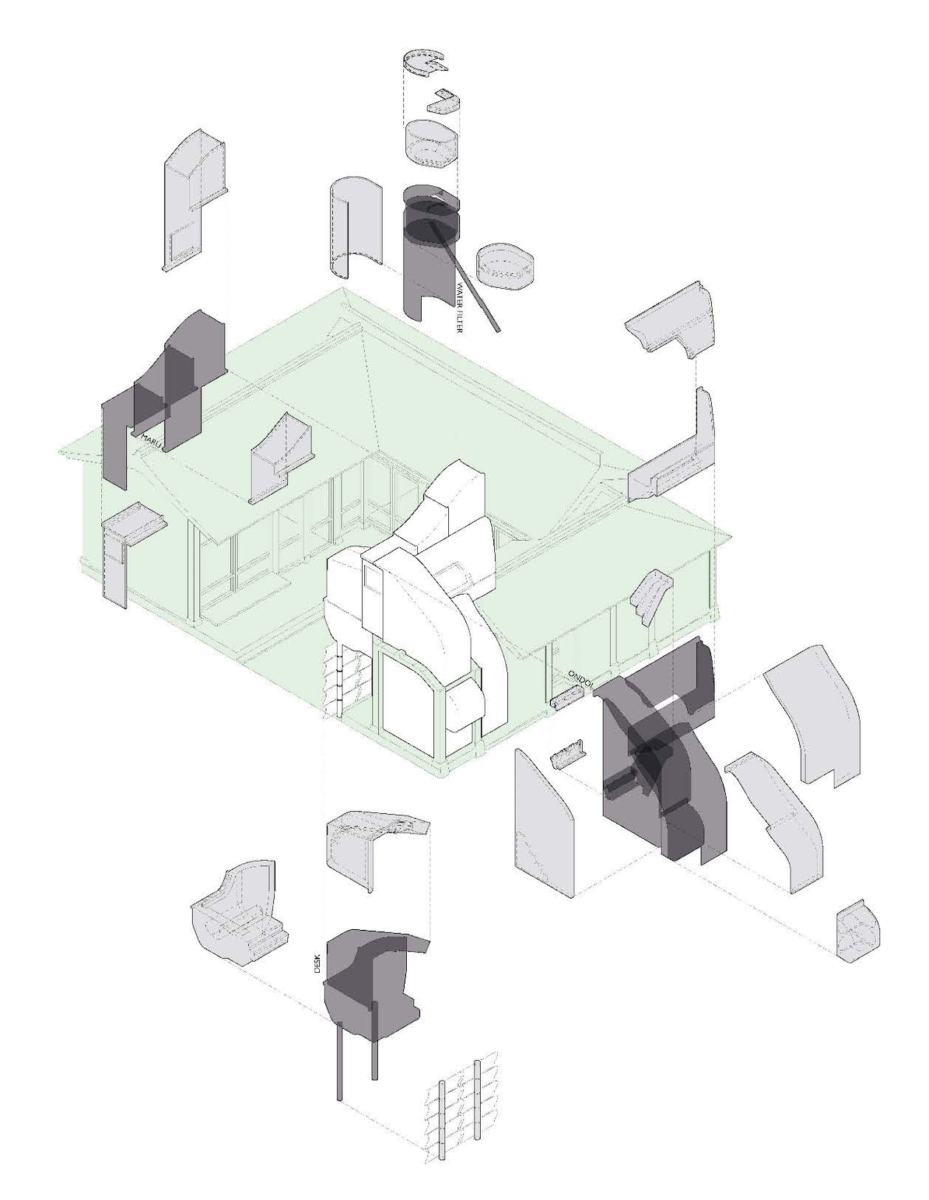

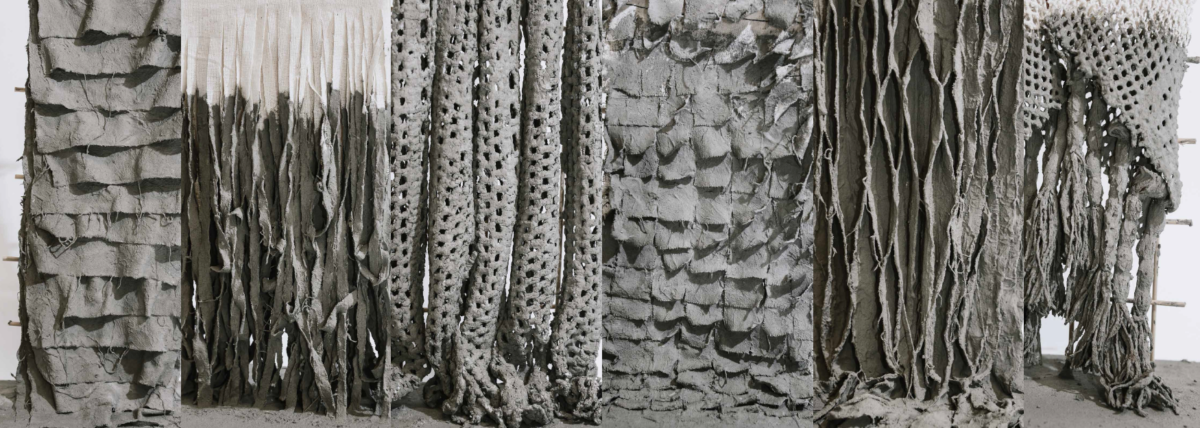

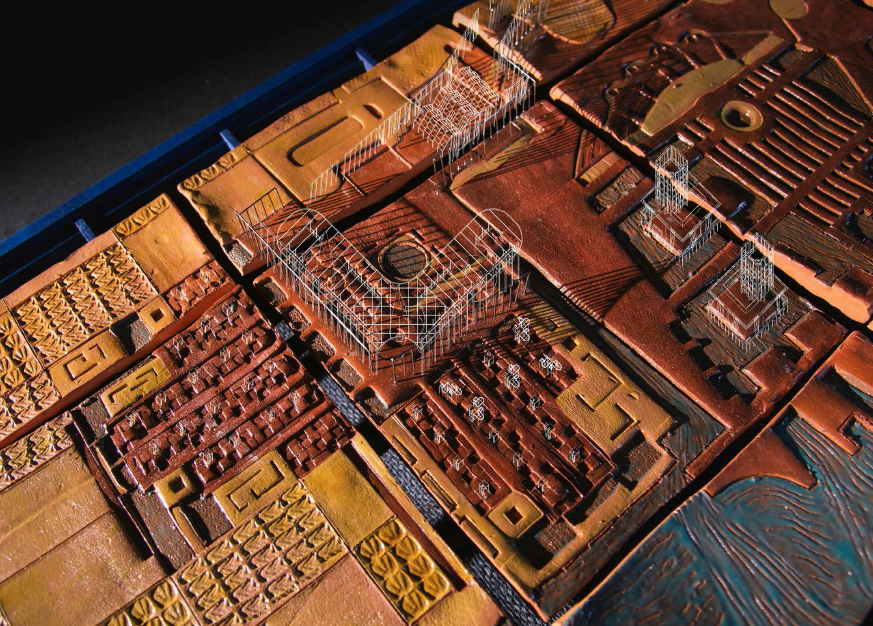

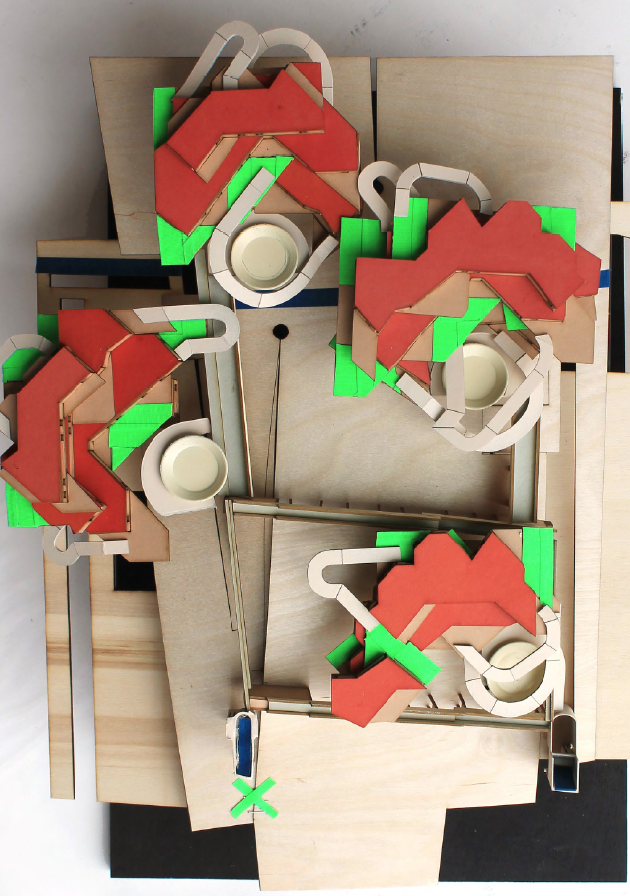

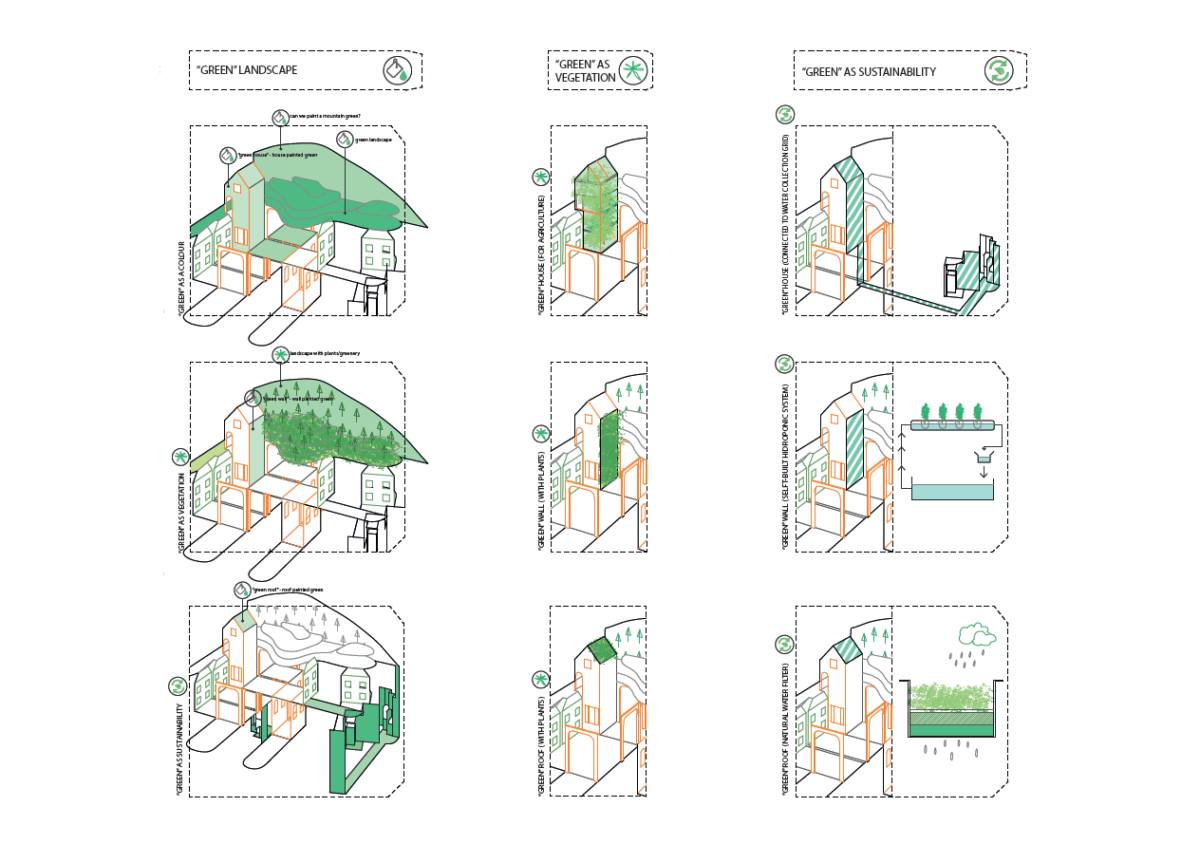

Korean ceramic craft was once prevalent in Seoul but is now found on the outskirts of the city. Buildings and crockery in Seoul are now predominantly steel, not clay. Taking inspiration from the urban courtyard typology of the Hanok; its ondol (heated) and maru (ventilated) floor, the project reintroduces environmental diversity into homes in Seoul.

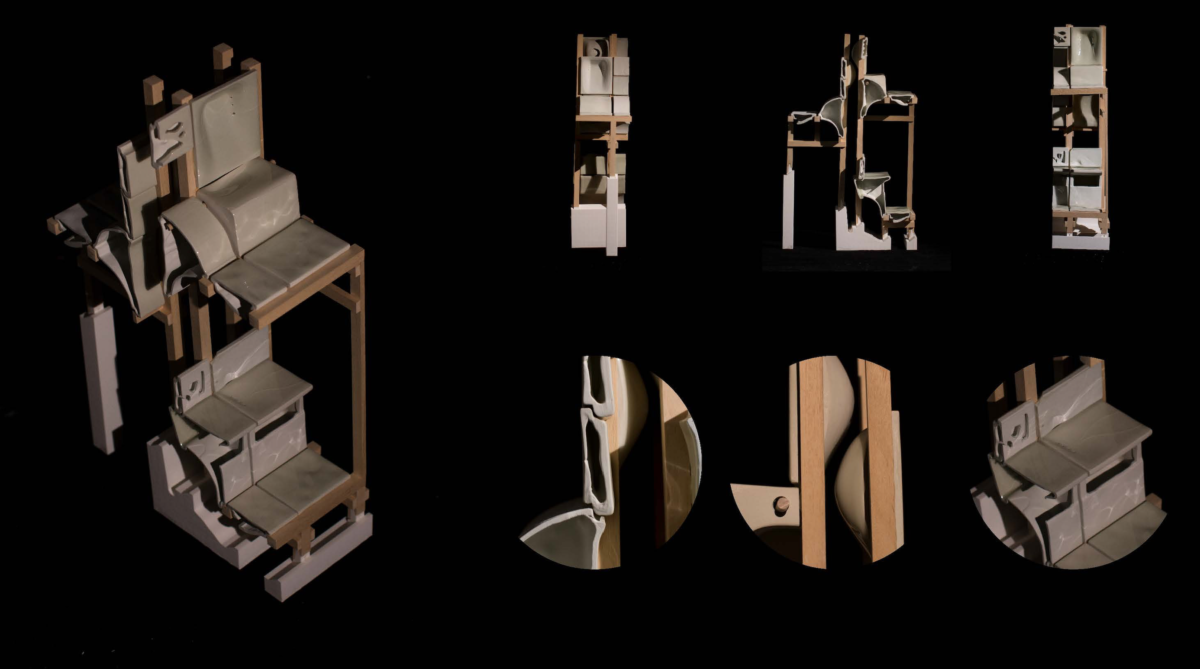

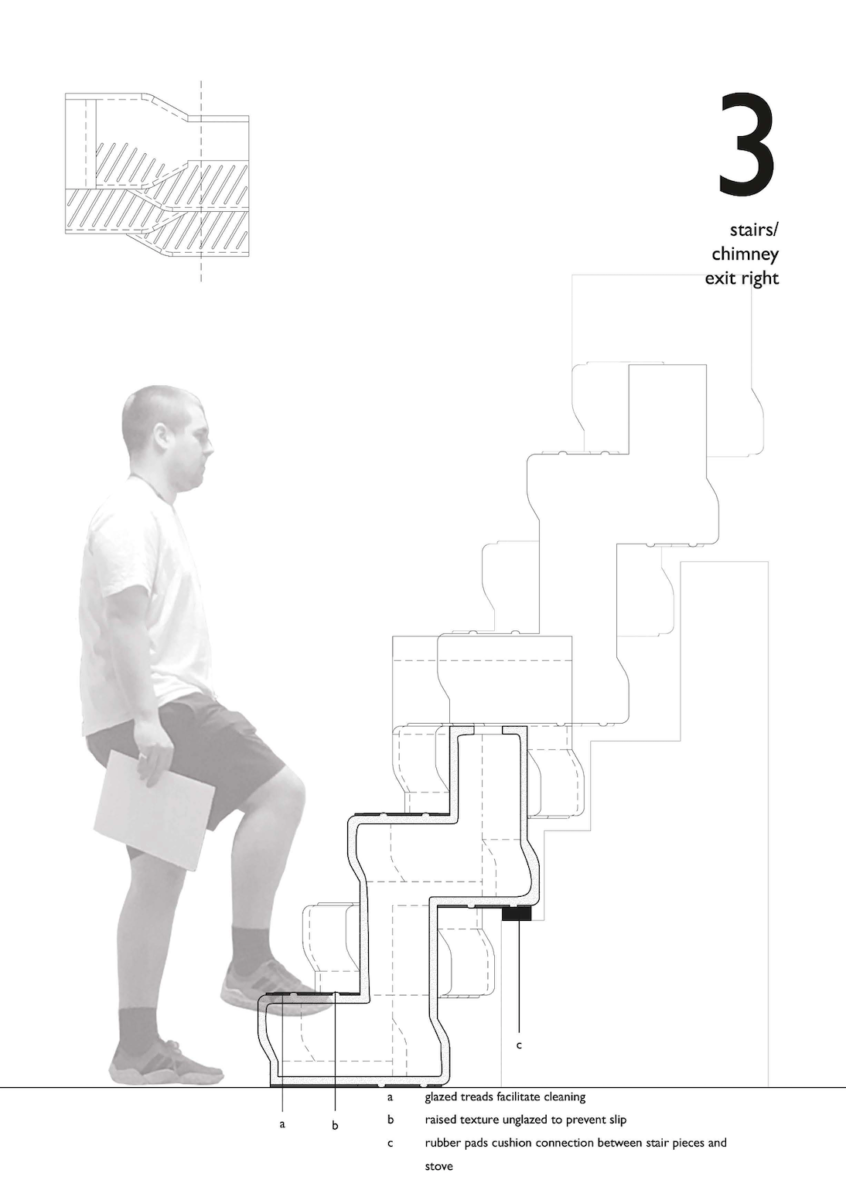

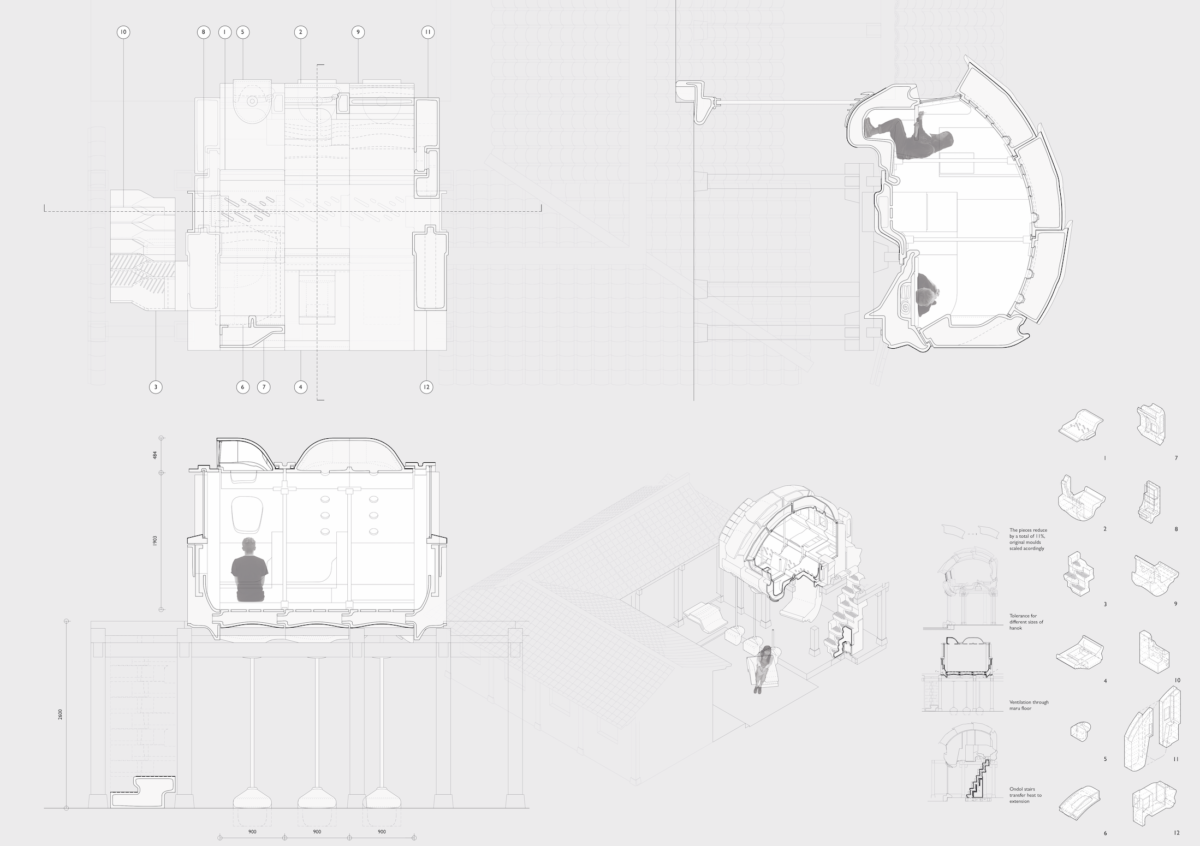

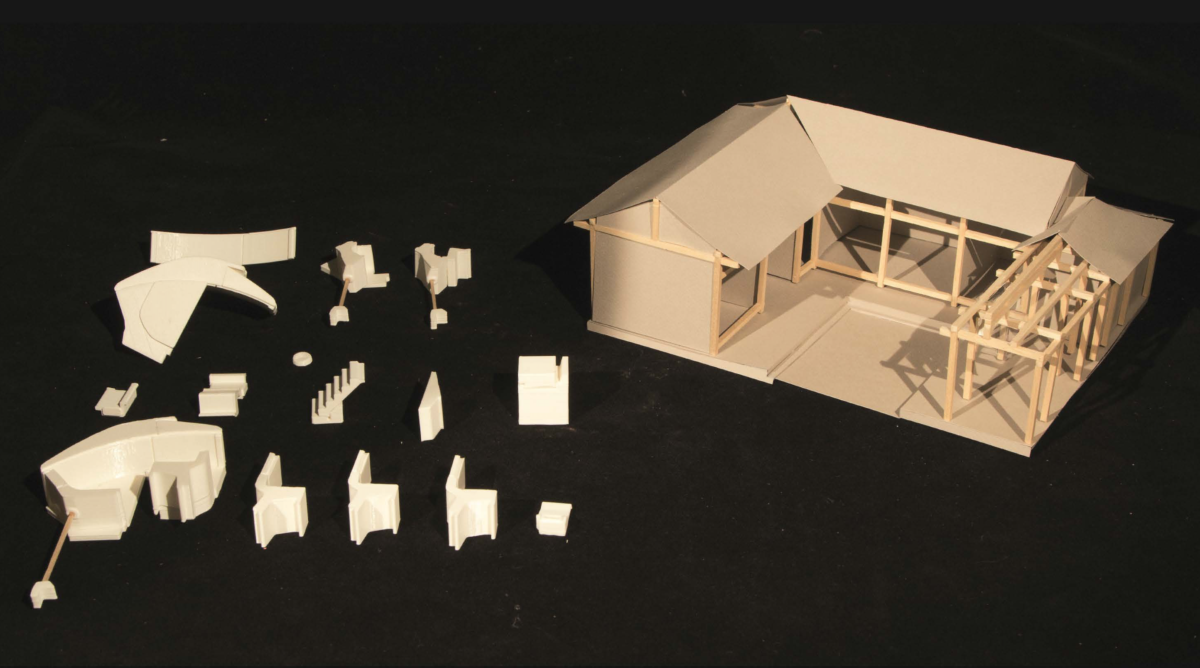

The diverse Hanok floor encouraged a sedentary living condition, harnessing the thermal properties of the floor and using it as furniture. As the typology has been adapted over time some of this diverse environment has been lost. In response to the dual role of floor as furniture, slip cast ceramic extensions, built to lodge into the original timber frames of the Hanok will act as built-in furniture. In themselves they can also be used as individual furniture pieces elsewhere. The pieces are designed to contribute to the environmental diversity of the ceramic house and this influences the inhabitation within.

Each piece is formed in plaster moulds and fired in climbing kilns in Seoul as a recognition and experience of Korea’s ceramic tradition within the city. The build is slow and celebrates the application of craft within a community. Extensions can be built up over time in a suitable configuration for the existing home, with each piece ceramic furnishing.

The project examines ceramic craft at a furniture scale and how this might question existing inhabitation. The ceramic house proposes a crafted installation of environmental diversity to reintroduce a tradition which has been lost in the centre of Seoul.

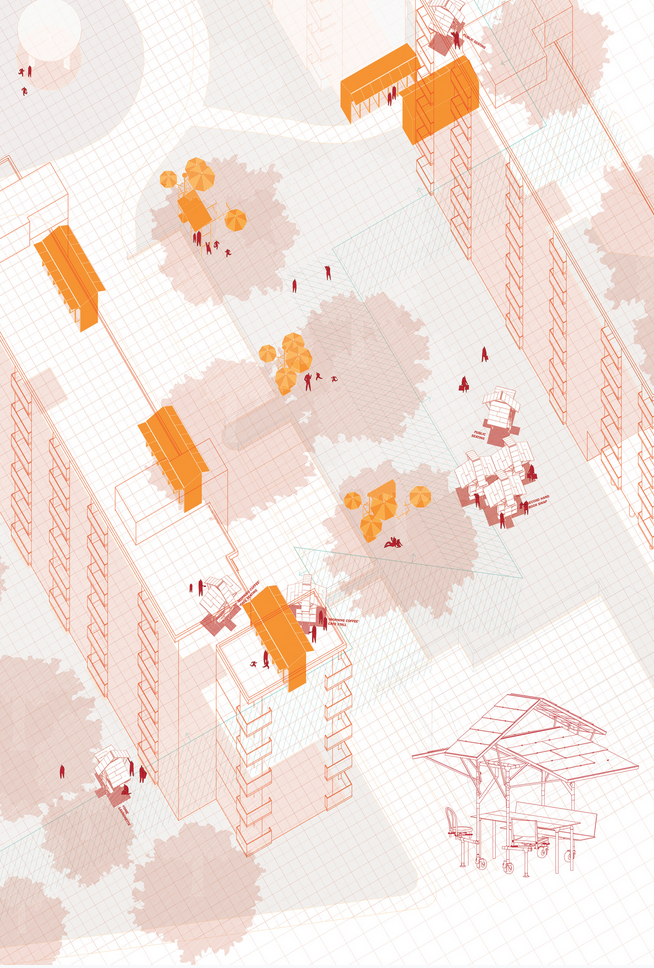

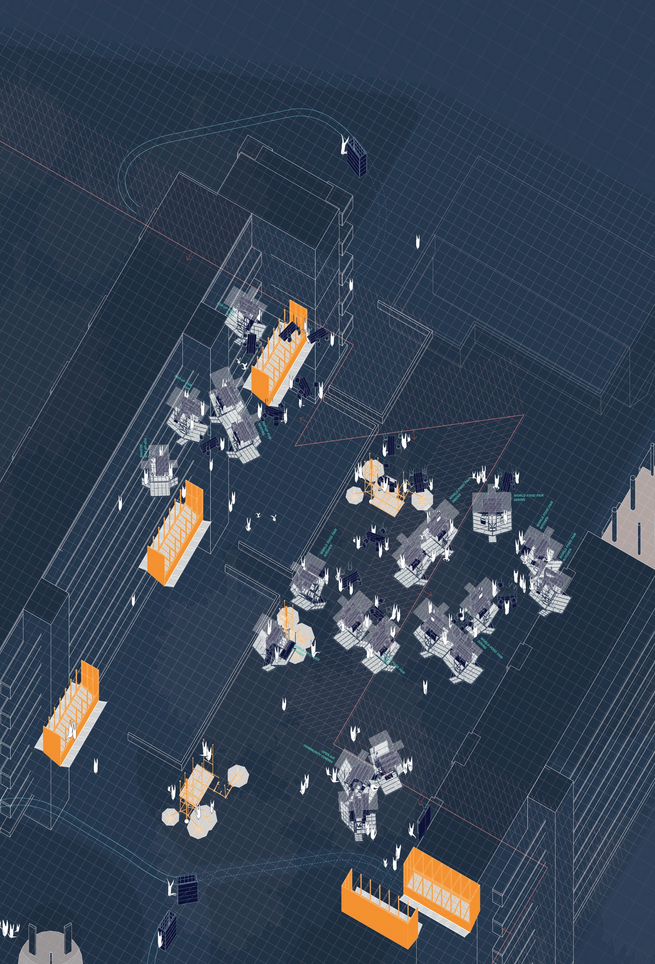

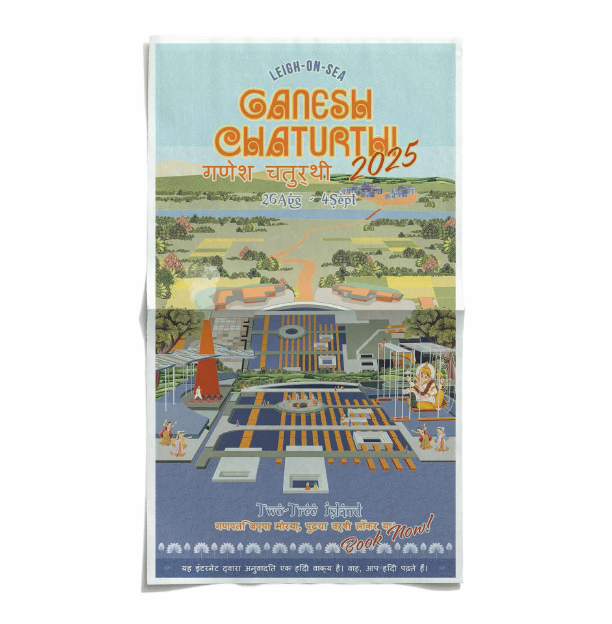

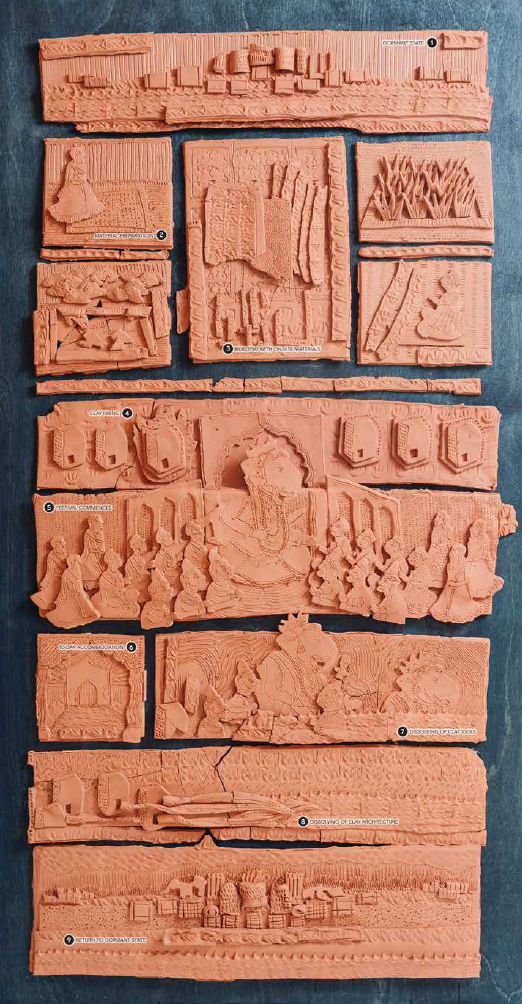

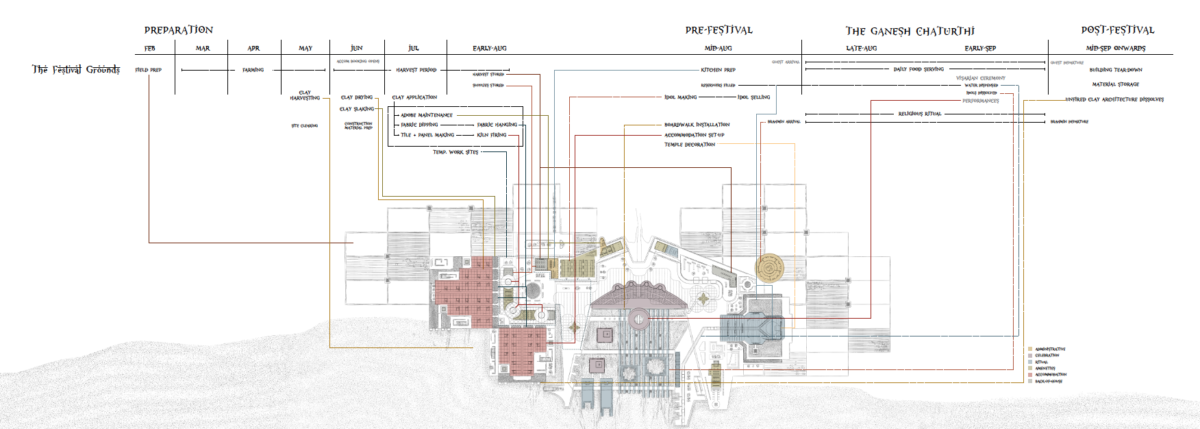

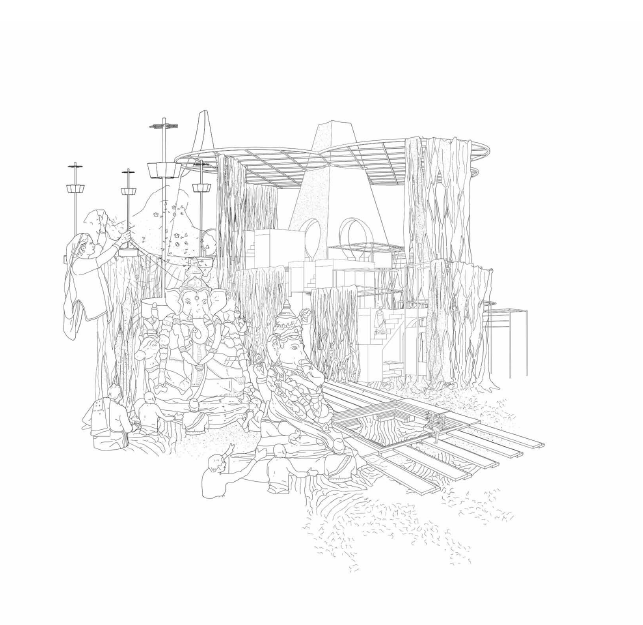

Ganesh Chaturthi Festival 2025 in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

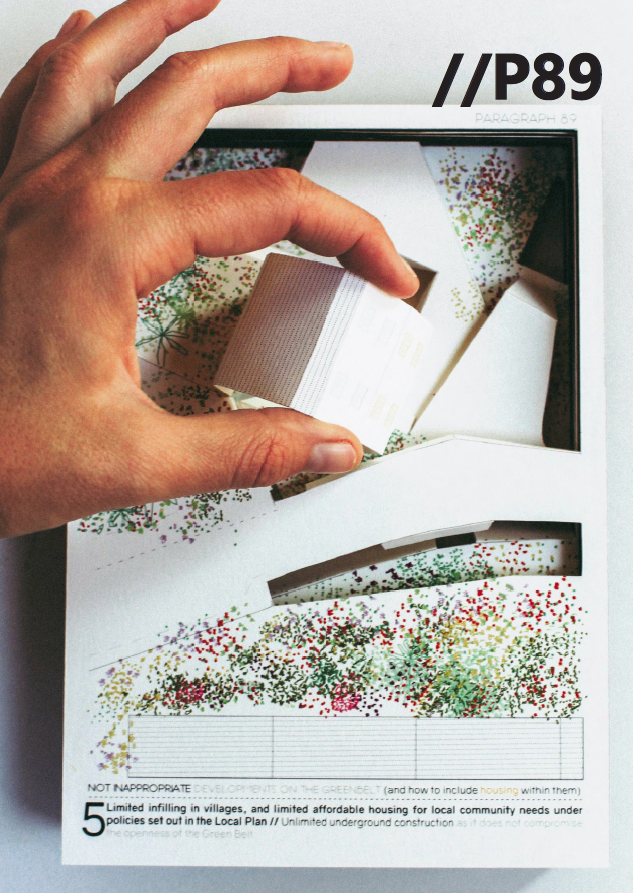

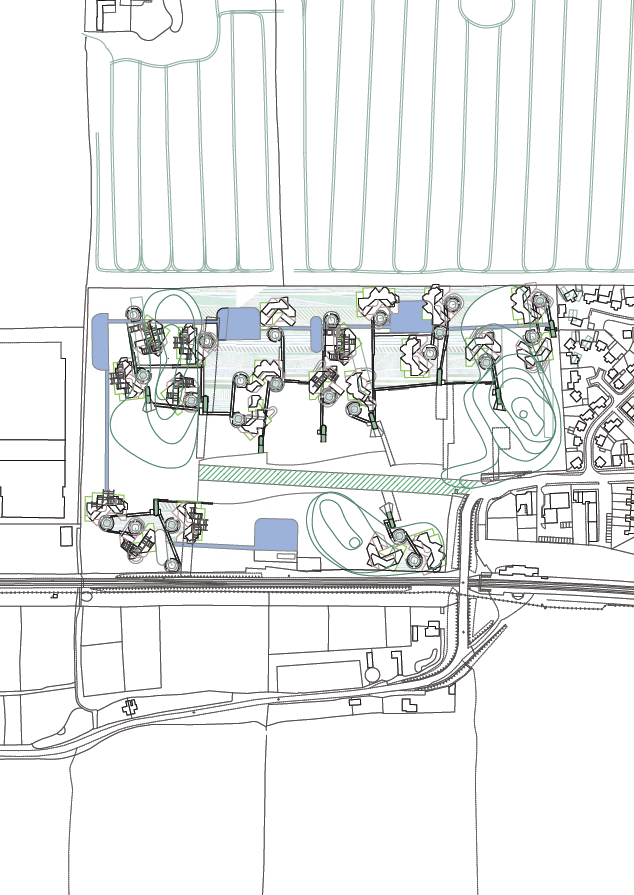

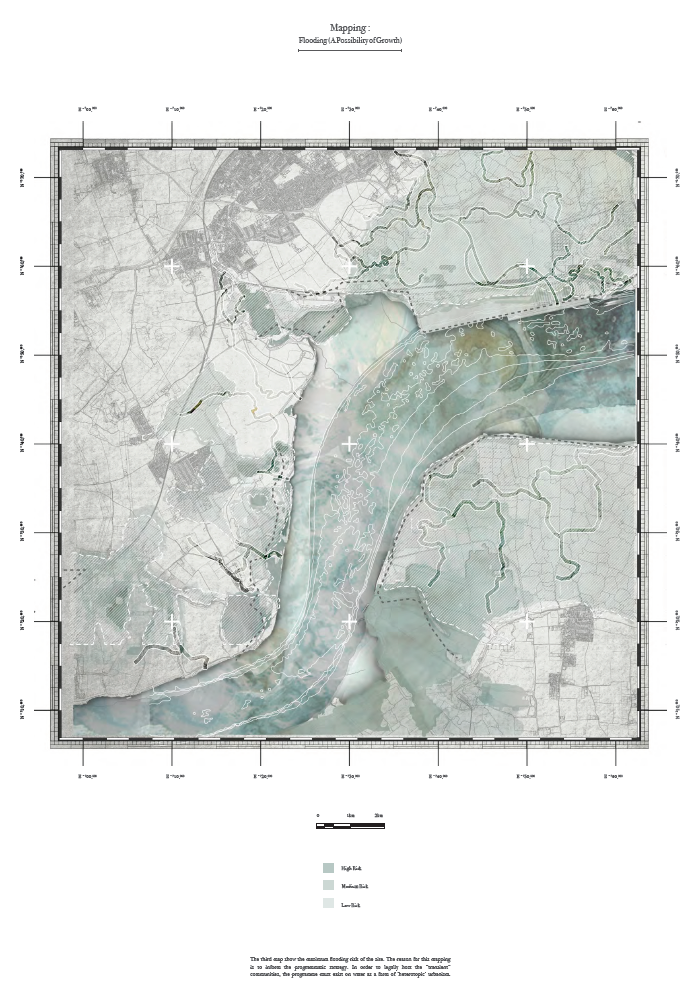

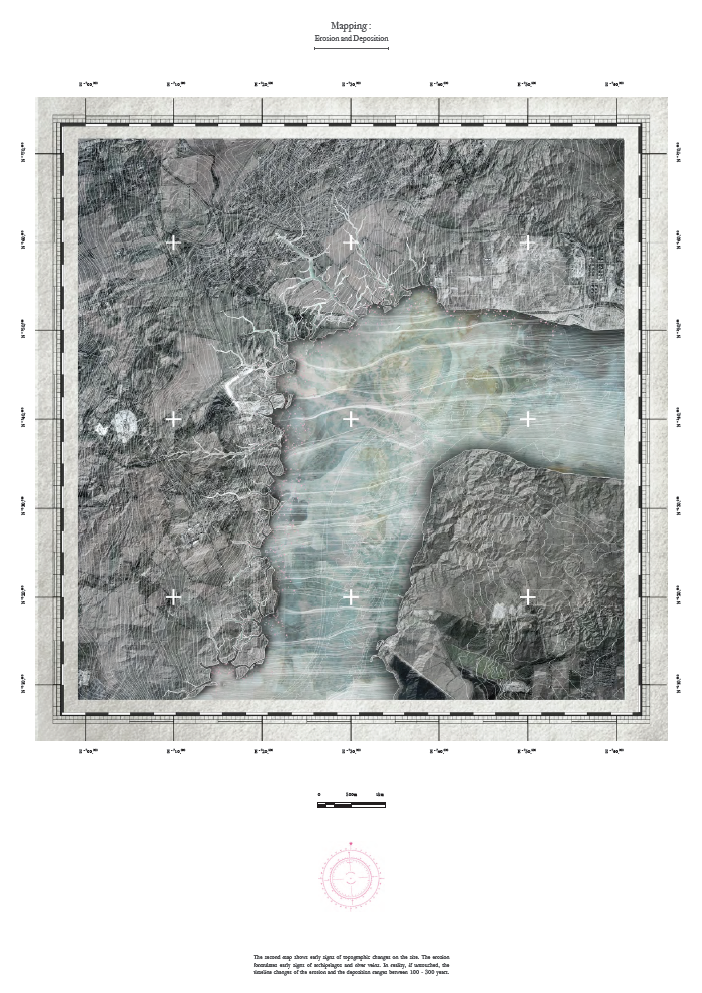

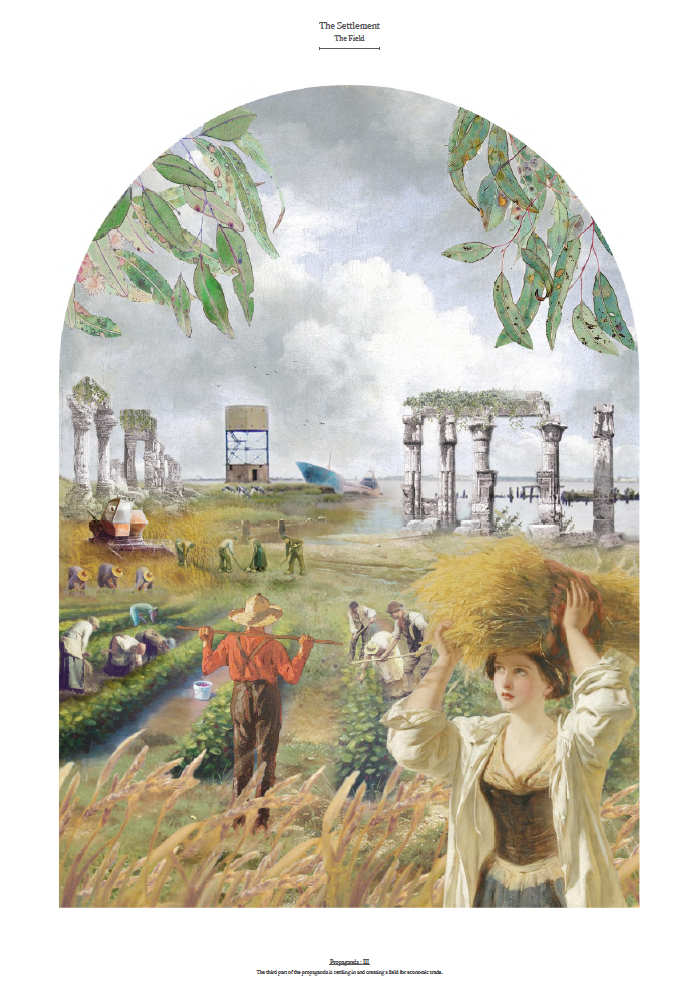

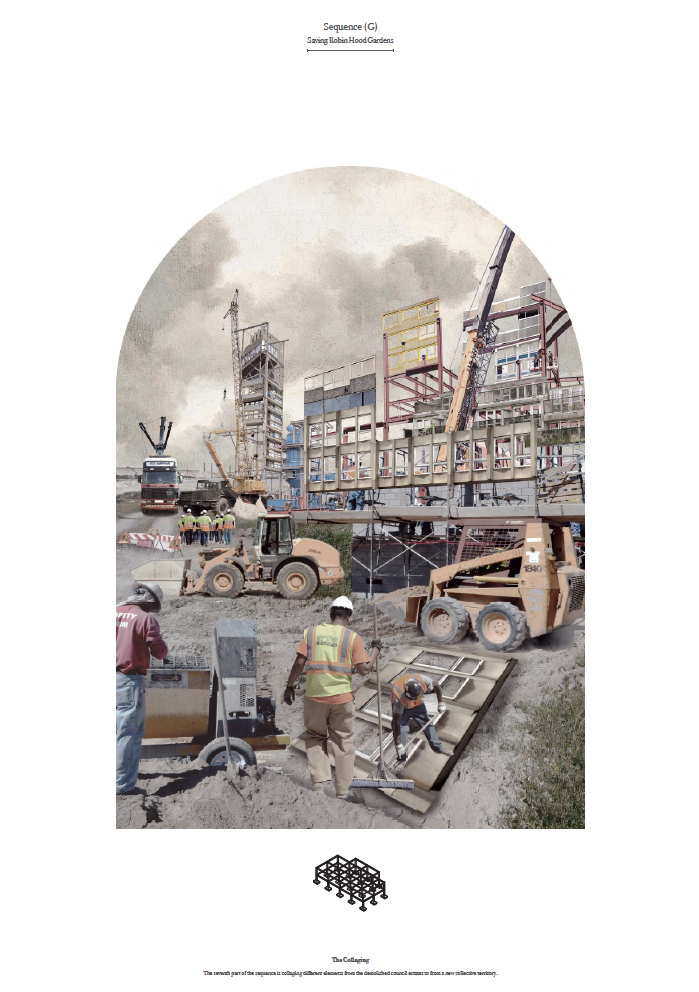

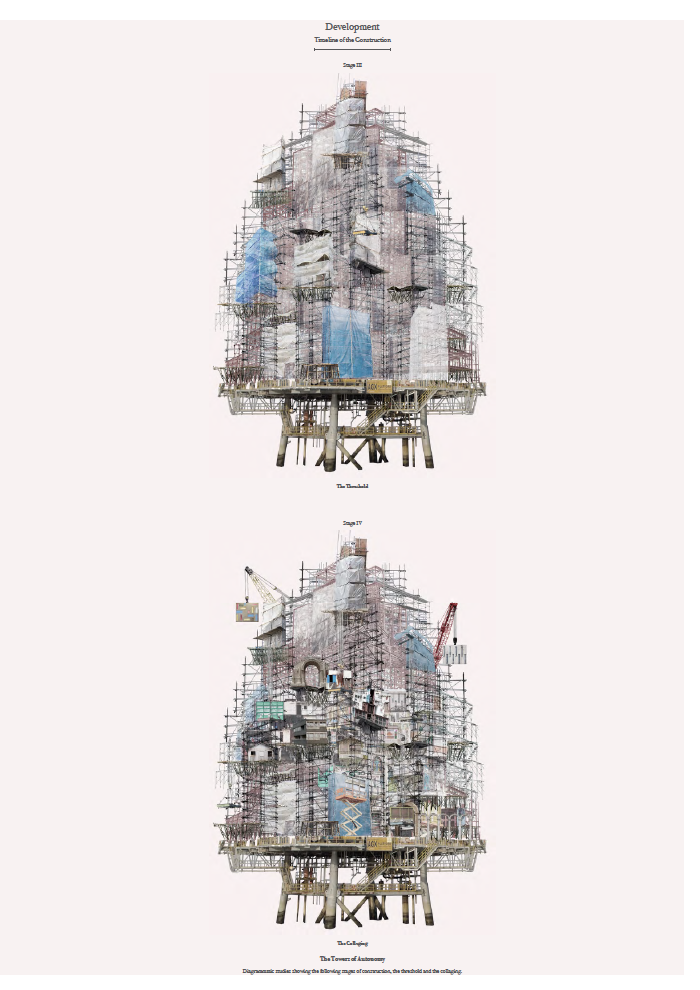

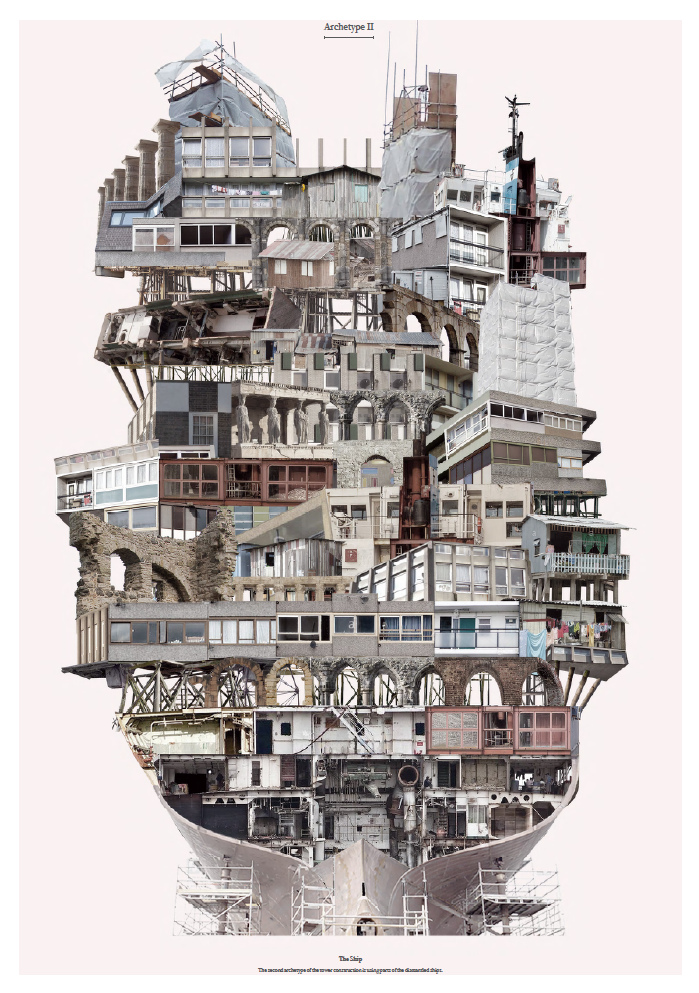

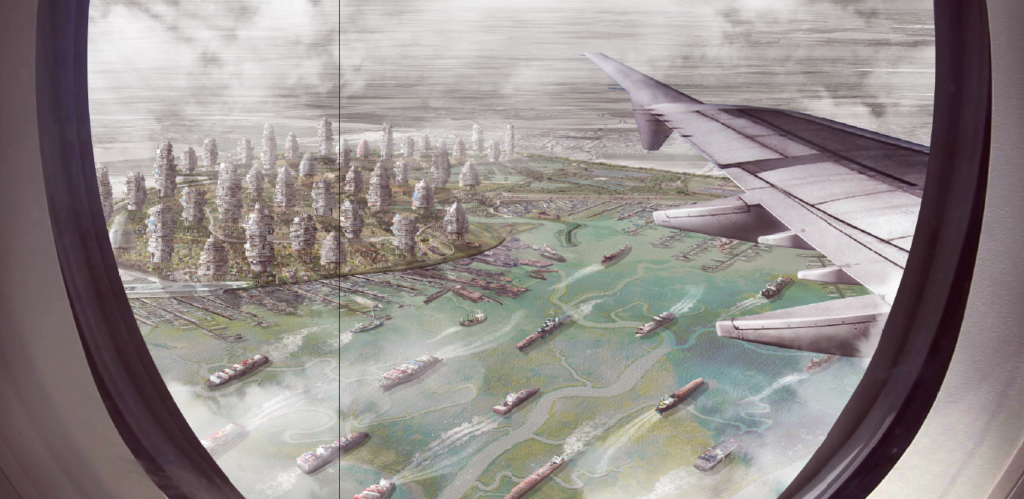

Unlocking land in the Greenbelt surrounding London.

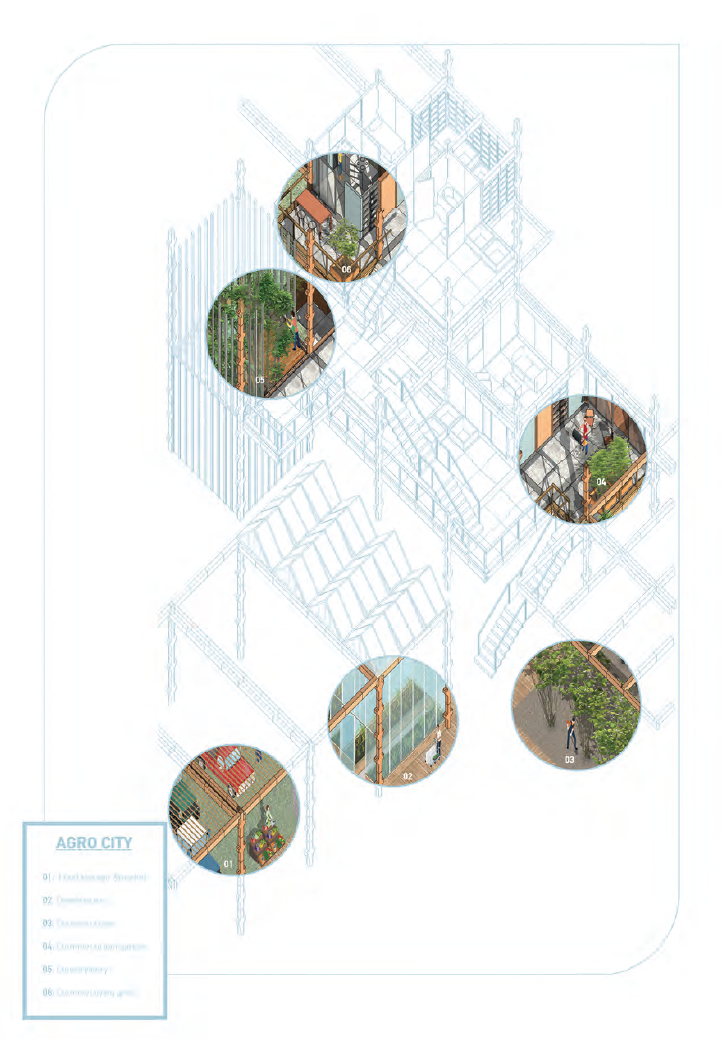

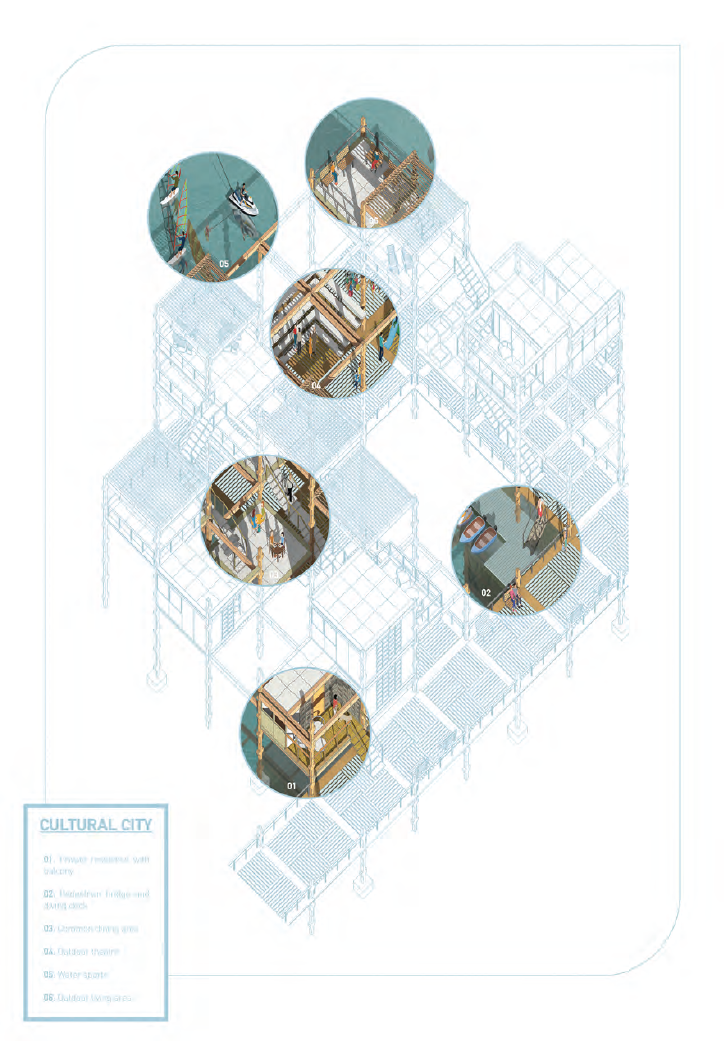

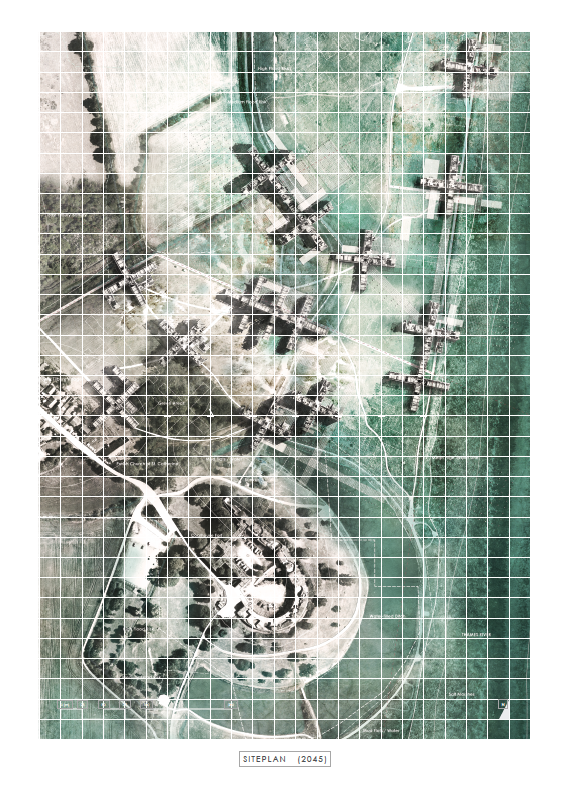

New Pilot Cities in the Thames Estuary

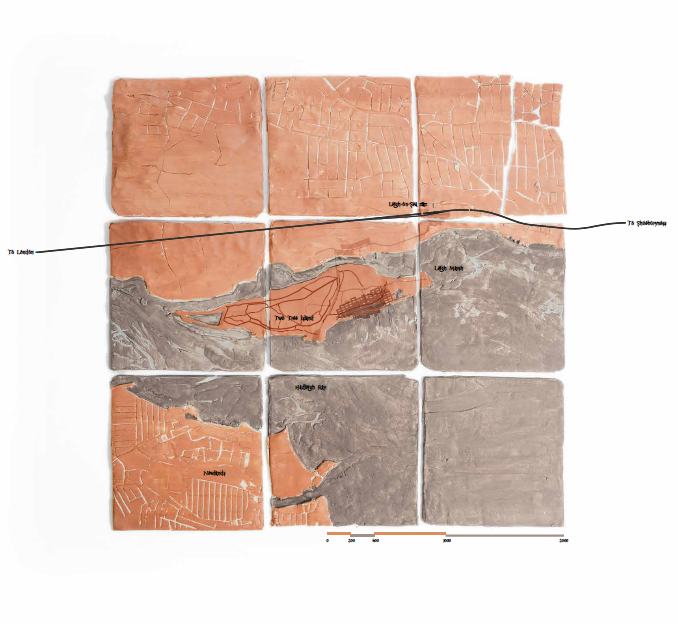

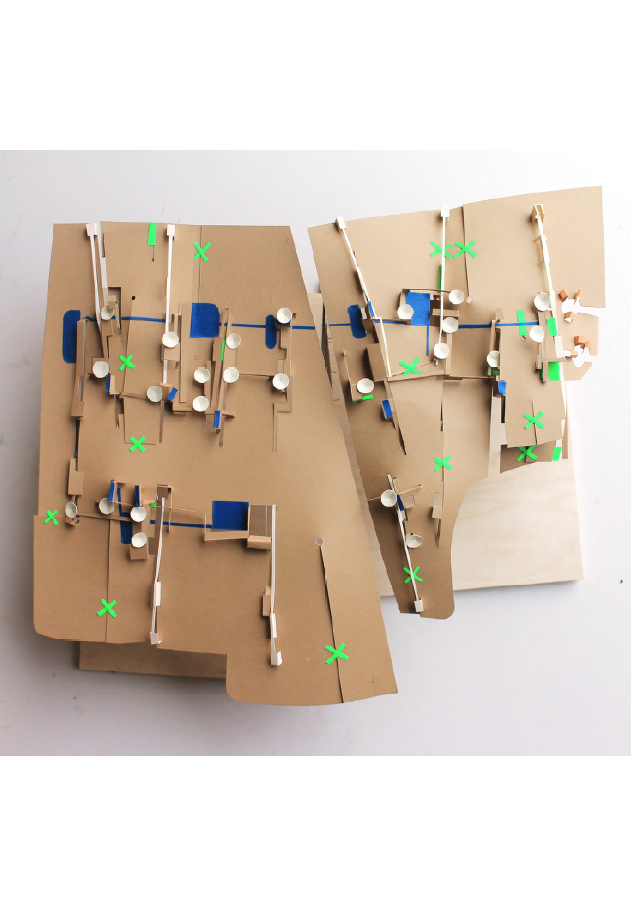

Essex Homelands – Inhabiting a Memory Landscape

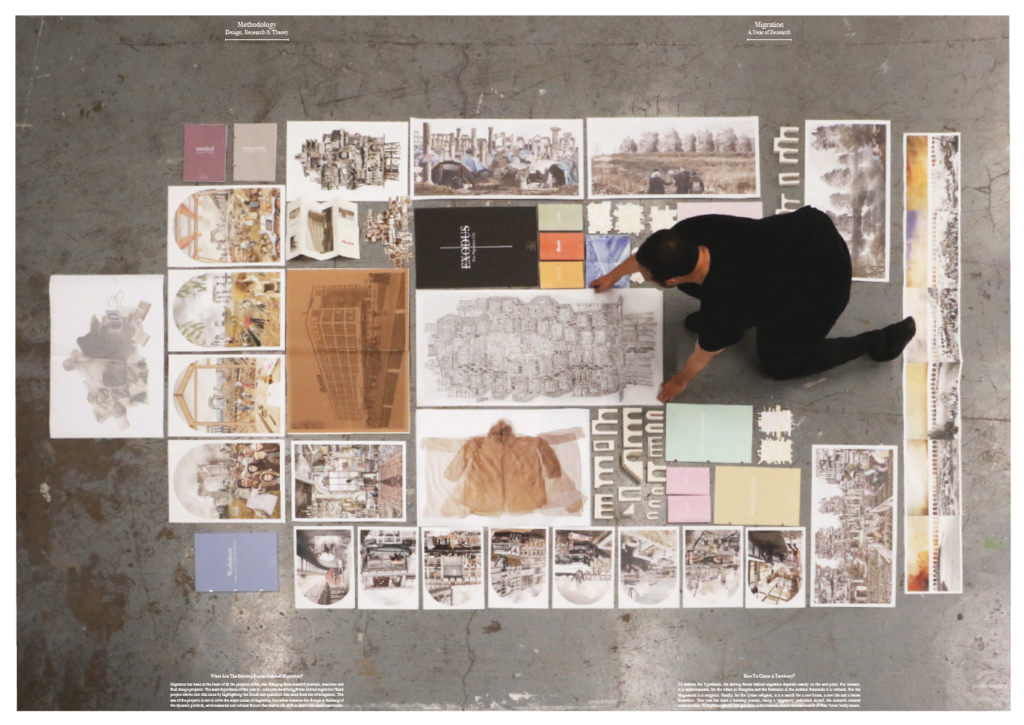

EXODUS

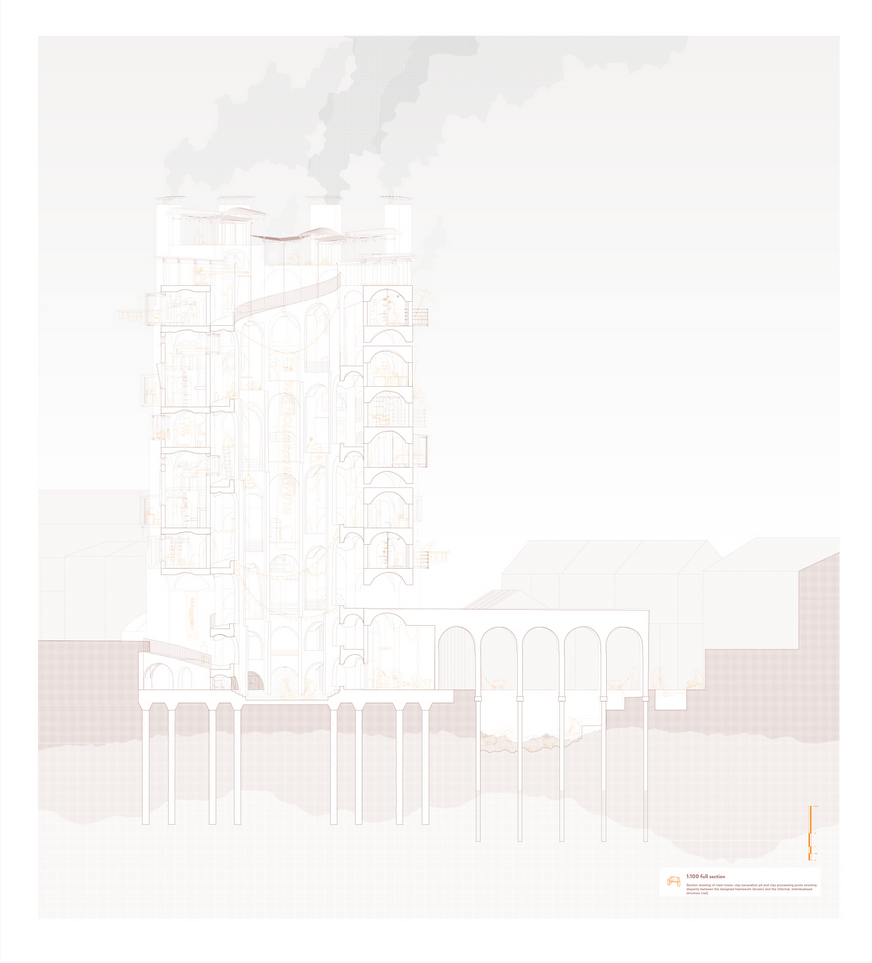

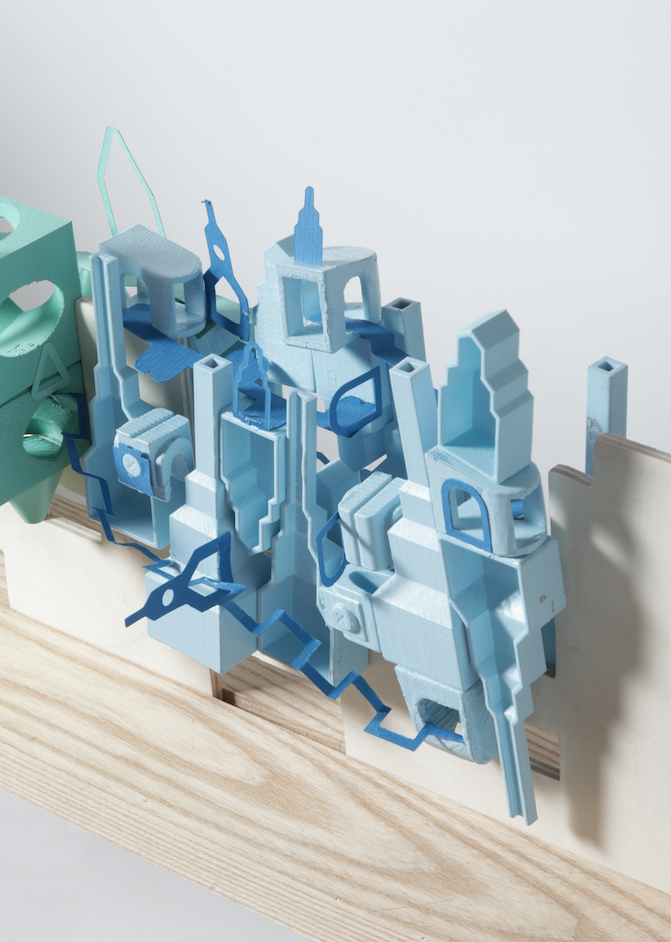

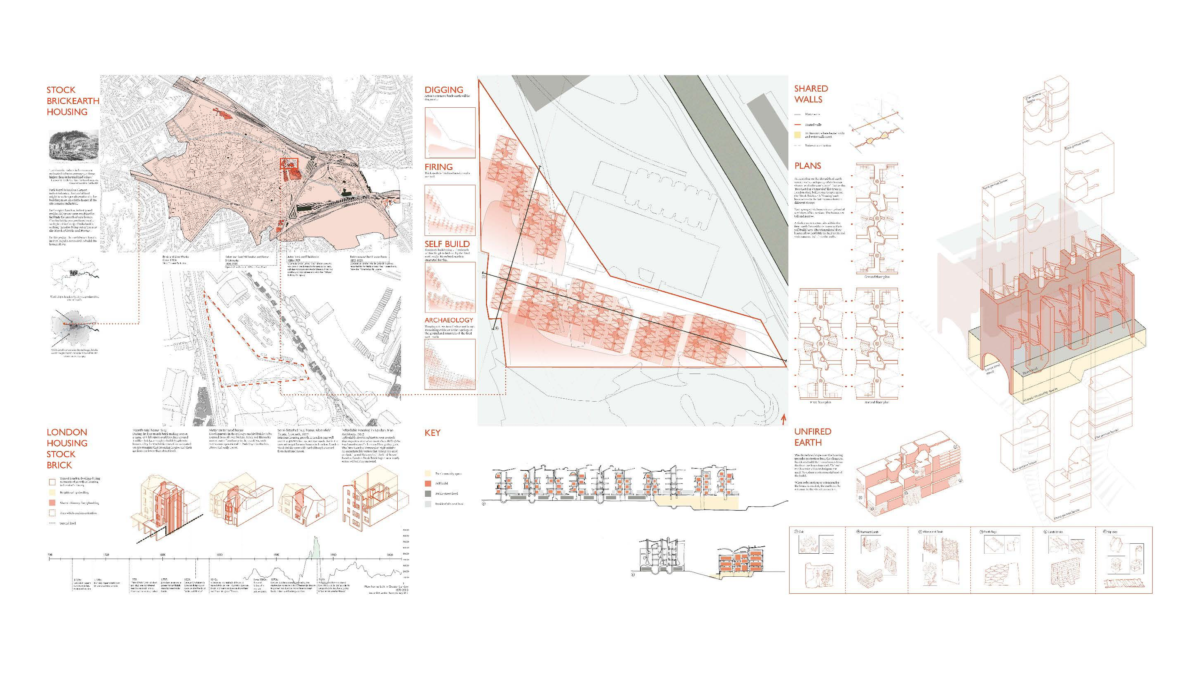

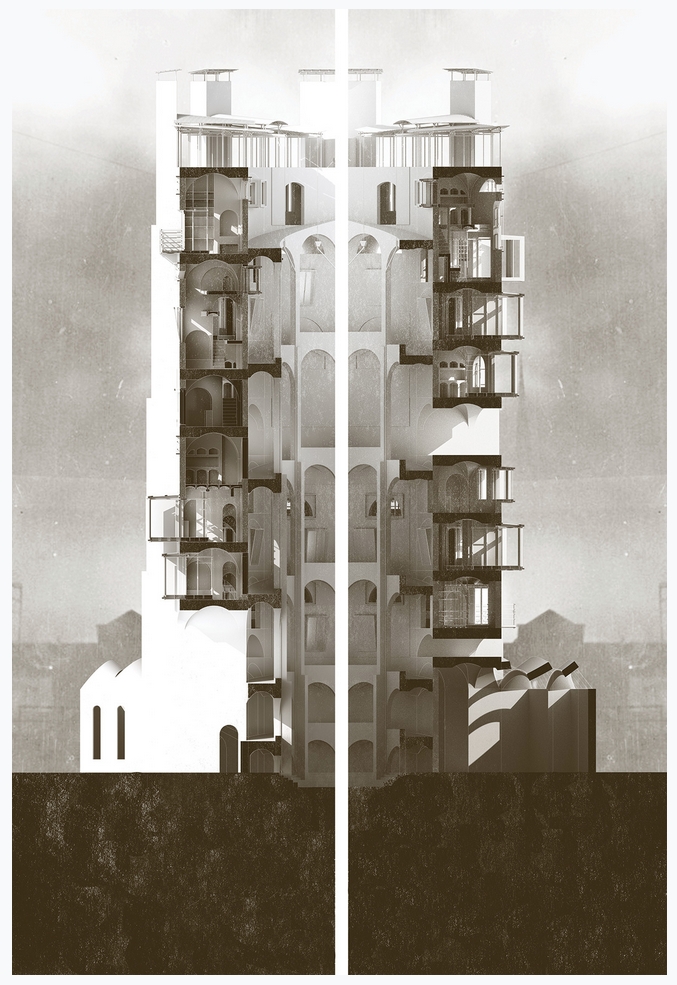

Clay Housing Tower next to thr Regents Canal in Ladbroke Grove, London