Tag: history

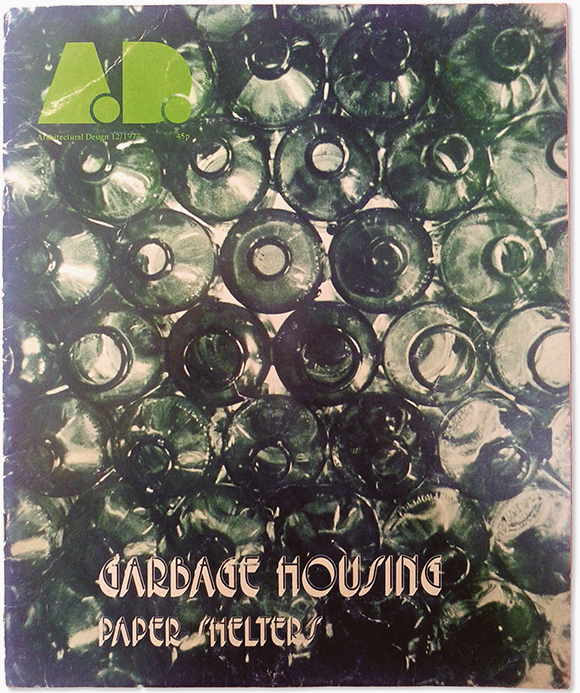

Recycling seems to have finally become mainstream – thanks god for that! But it hasn’t always been like that. The throwaway culture started a long time ago and it seems some visionaries have seen the writing on the wall long before the rest of us has caught up to this.

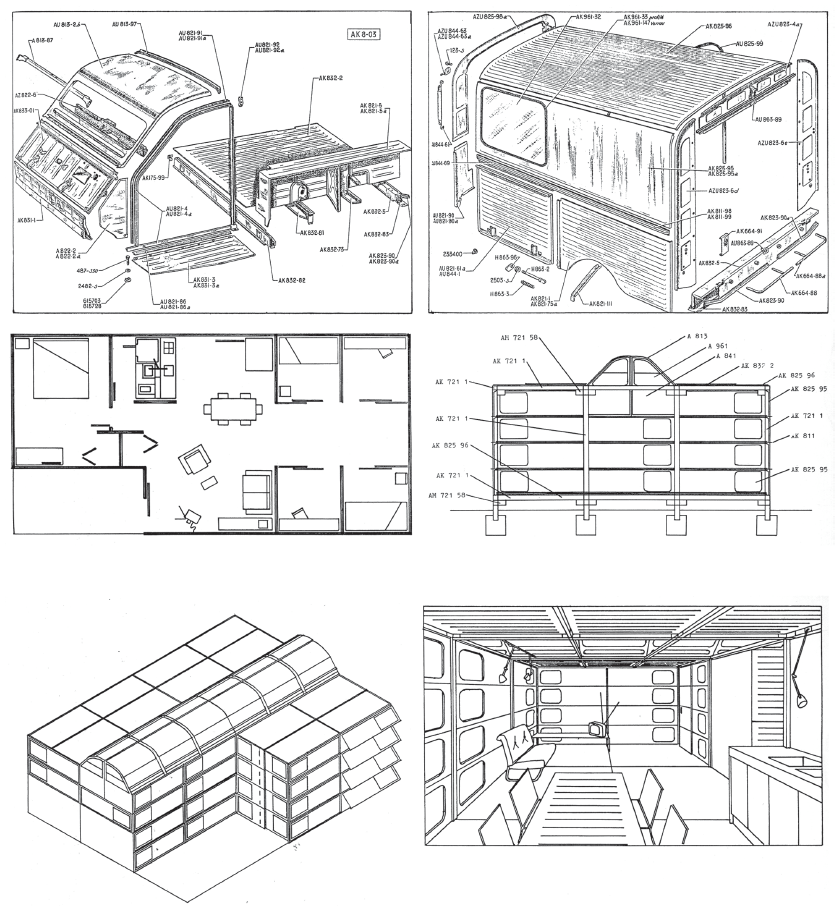

One of these visionaries has been Martin Pawley, a british architect who promoted his ideas for the garbage housing as early as 1975.

Nowadays we all talk about recycling, how we should avoid creating more and more waste to pollute our planet.

The designer Aino Aalto resting on a lounge chair on the solarium terrace of the Paimio Sanatorium in 1932. Photo taken by Alvar Aalto.

In the 1920-1930 a new movement in architecture emerged from Europe. Modernism promoted an architecture that was characterised by its clean lines and white walls. Functional spaces that were pure and free of any decoration or ornamentation associated with historical architecture.

But on closer inspection this new movement was not about style, about dismissing the architecture of the past on aestetic or purely formal grounds. It has much deeper roots in the desire to eradicate tuberculosis, a disease that, at the time, didn’t have a medical cure.

Robert Koch discovered the tuberculosis bacillus in 1882 but until 1949 there wasn’t an effective medical treatment for this disease. It had been understood that the disease spread and was dormant over long periods of time, hidden the dust of the houses with a poor ventilation aggravating the situation. In 1900 tuberculosis was responsible for 25 percent of all deaths in New York.

Modernism must be seen as a reaction to this crisis. At the time the only real cure for the disease was what was called the Freiluftkur, where a person was treated with plenty of fresh air, lots of sunlight, and nutritious food. The standard ‘cure’ for TB was primarily a change of the environmental conditions. Very soon architects responded to the challenge by devising an architecture that was dominated by clean lines (that were easy to be cleaned), surfaces free of ornamentation (trapping dust and spreading the disease). Buildings were elevated off the ground (to allow air to circulate and to remove the inhabitant from the damp ground), walls were penetrated with large windows (allowing in sunlight and fresh air). These building were not machines for living, they were machines for healing.

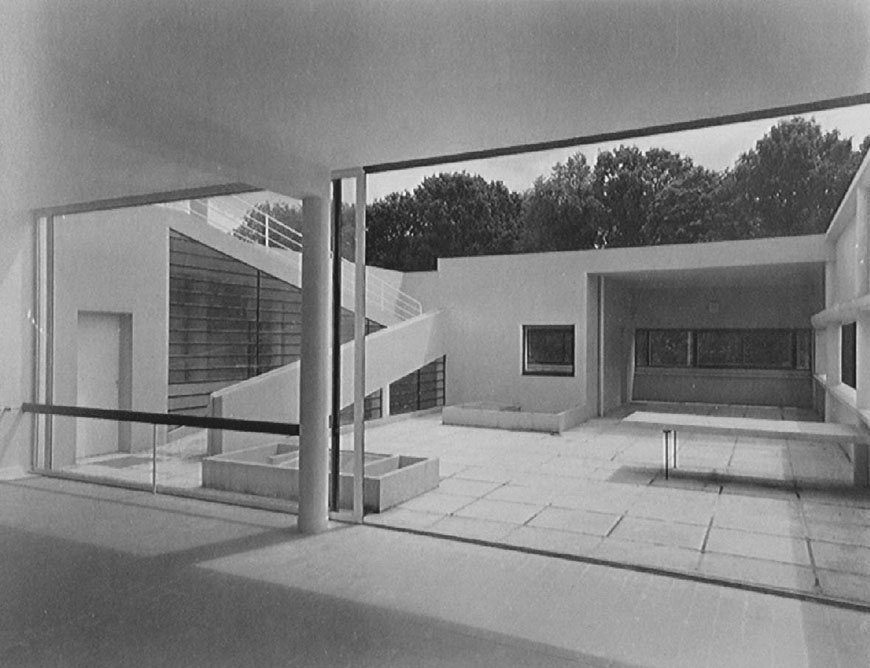

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoy, Paris, 1929

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoy, Paris, 1929 Open airy spaces, light flooding into the living spaces.

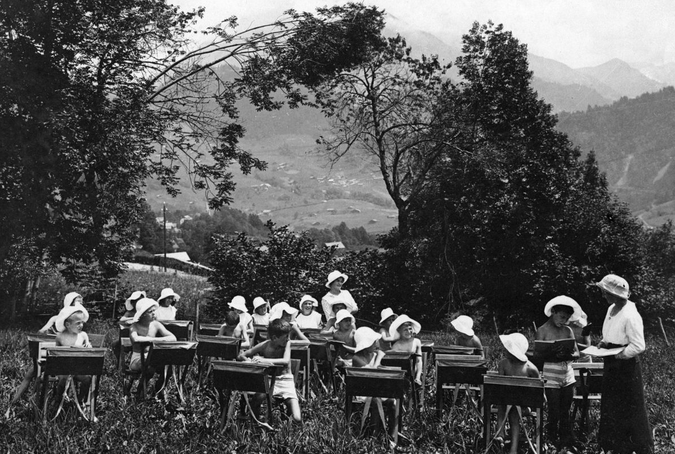

Children being taught in the open air, ca. 1920

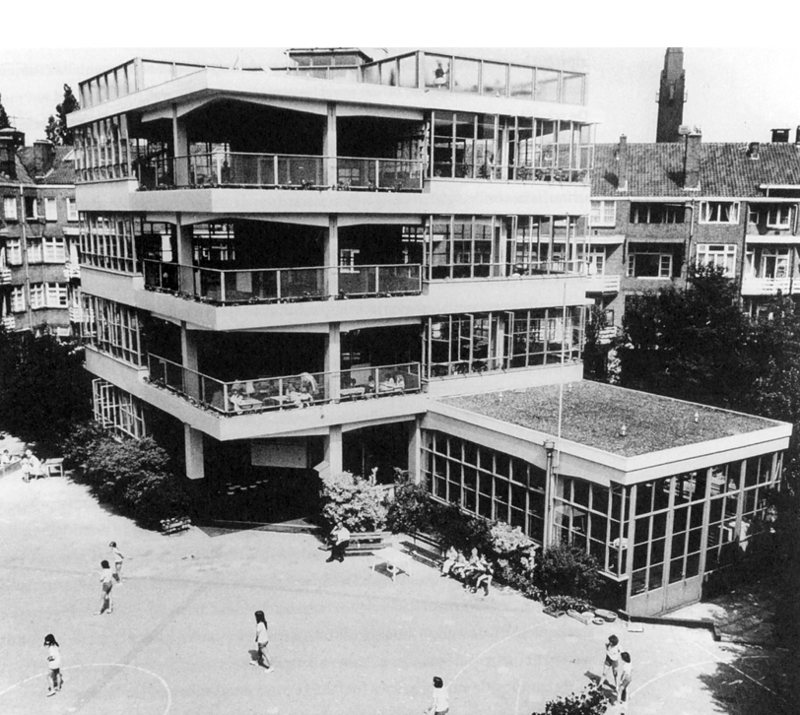

Jan Duiker, Open Air School, Amsterdam, 1927

x

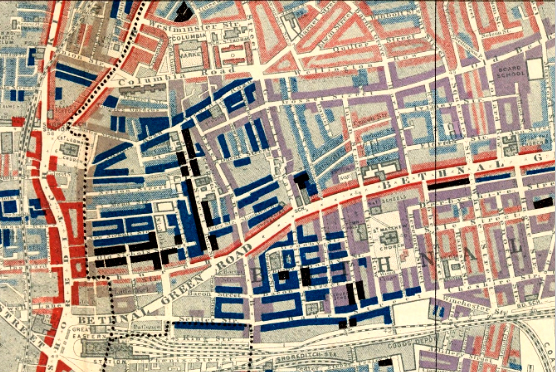

Charles Booth’s Descriptive Map of London Poverty 1889 showing The Old Nichol area, later transformed into the Boundary Estate. Areas in black are indicating ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi criminal.’

Old Nicol Road Slums / Boundary Estate

At the height of the British Empire, with Queen Victoria ruling over large parts of the world, unimaginable riches flowed back to England from the overseas colonies. The new global trade routes made English industrialists immensely wealthy. Like today these riches were not spread equally across the population and most parts of London of the late 19th century was a dark place to live in. With people moving into the big cities looking for a better life, resulting in poverty and misery – this created huge overcrowded slums.

At the time hugh areas of land could only be leased for a maximum of 21 years. This mean landlords had no interest to create building that would last. But even this was too much for some peopel who woudln’t even be able to rent a bed for a night – being forced to get a space in in a room with robe beds – ropes to lean over and rest for the night.

‘Rope beds’ were a cheap but misreable way to spend the night in a doss house.

While some of the luck inhabitants were able to afford a space in a sleeping coffin, the ‘Four Penny Coffins’.

‘Four penny coffins’ were a relative luxury compared to the alternatives.

With nearly 6000 inhabitants the area once called Old Nichol was one of the worst slums of the East End in the late 19th century. Immortalised in the novel ‘A Child of the Jago’ by Arthur Morrison the area was highlighted on the Charles Booth’s poverty map is inhabited by the “lowest class, loafers, criminals and semi-criminals”.

The local reverent, Osborne Jay initiated the rebuilding of the slum which created the Boundary Estate, one of the world’s first council estates. The new buildings were influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and were built to a high standard. Housing over 6000 residents each flat was designed to maximise good light and air for the residents. Sadly, only 12 of the original slum residents moved into the flats, the others moving on to new cheaper areas in Bethnal Green or Dalston, taking the overcrowding with them.

The crisis of the clums led to the invention of a new housing typology, the council house.

Grim Realities of Life in the Slums

.