Category: 2022

a festival of the mundane

During his lifetime the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer completed around 50 paintings of which 35 survive today. Most of the paintings depict domestic scenes. It is remarkable that 19 were painted in the same room, showing often the same people. The scenes involve normal people doing ordinary things. But looking closer each element has been carefully chosen, playing a predetermined part in an everyday story. The real subjects of Vermeer’s paintings are not the characters depicted; it is the everyday space, the light, the materiality. Being ‘mundane’ is usually not a compliment, it’s seen to be dull, lacking interest or excitement.

This year PG13 will explore the ‘Everyday’ – looking in detail at how we live together and inhabit space, the routines informing architectures. The Everyday doesn’t need to be boring, it is you who must elevate it to greatness using imagination and innovation.

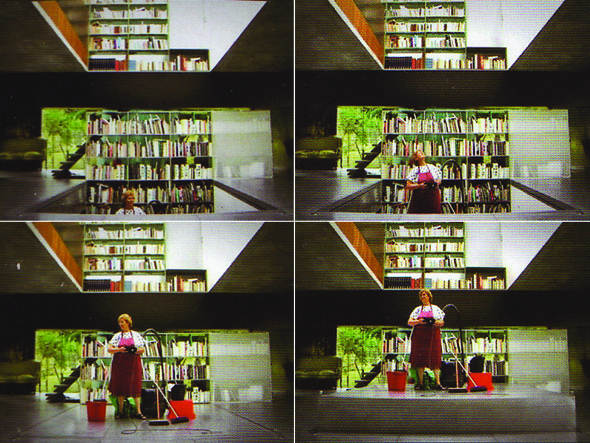

Stills from Koolhaas Houselife, Bêka Ila and Lemoîne Louise, Bekafilms, 2008

The film follows the housekeeper Guadalupe Acedo through her daily routines of looking after the house designed by Rem Koolhaas.

Interview with the filmmakers on YouTube:

Trailer on Youtube:

Johannes Vermeer’s paintings of the ‘Everyday’.

The Art of Vermeer:

http://www.essentialvermeer.com/vermeer_painting_part_one.html