Category: 2021

PG13_RADICAL

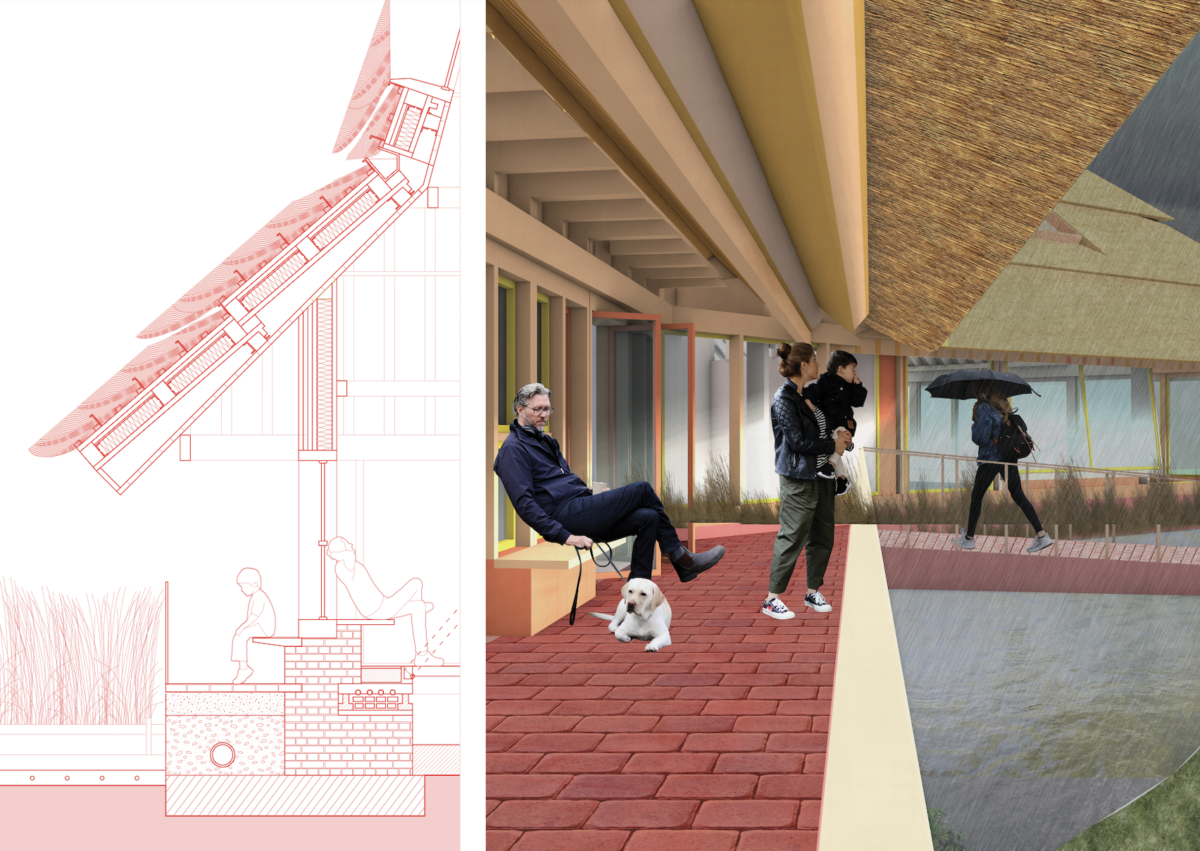

Nine Meals from Anarchy: A New Public House for East Tilbury

East Tilbury, a former Bata shoe company town, is typical of many parts of suburbia and rural England that are falling into a disrepair, defaulting to “commuter towns” and foregoing their own identity. In response to the erosion of a close-knit community, current residents aim to reinstate the lost shared elements and consciously build social value. Local decision making runs parallel with communal tasks such as, swimming, crafting, and preparing food. Through a new production, residents start to take ownership over their locality, causing the domestic to spill into the public. This project aims to redefine the public house as a community infrastructure that facilitates the coming together of residents. Taking cues from the masonry stove and the centrality of the chimney to living functions, the scheme examines the hearth as a potential space for cohesive social praxis.

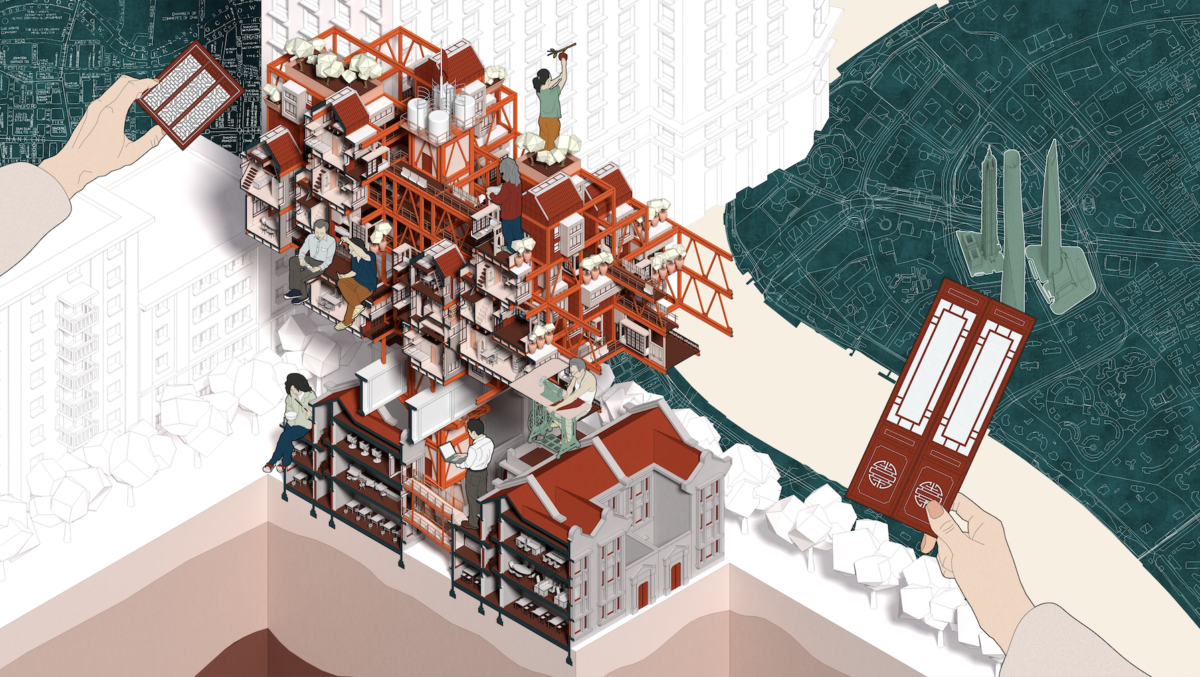

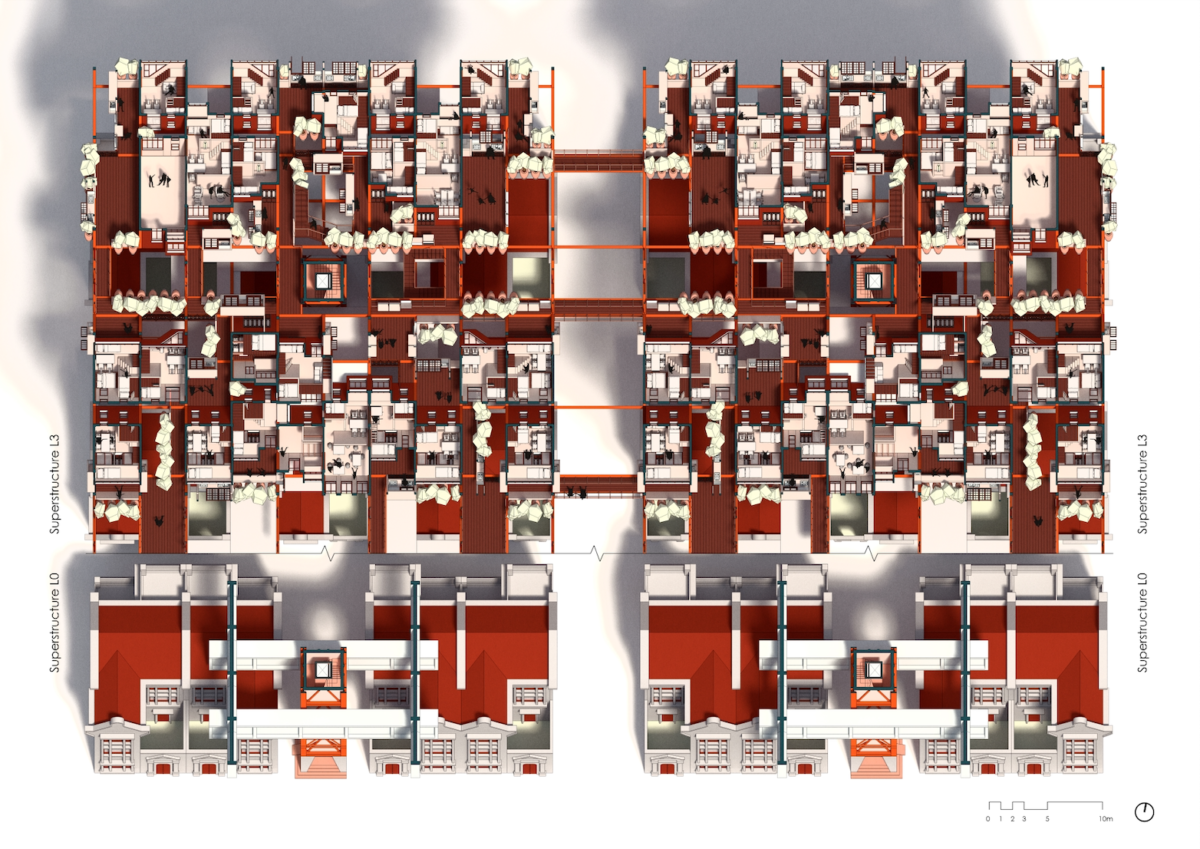

Yong’an Fang 2.0: Displacement-free Renewal of Shanghai’s Lilong

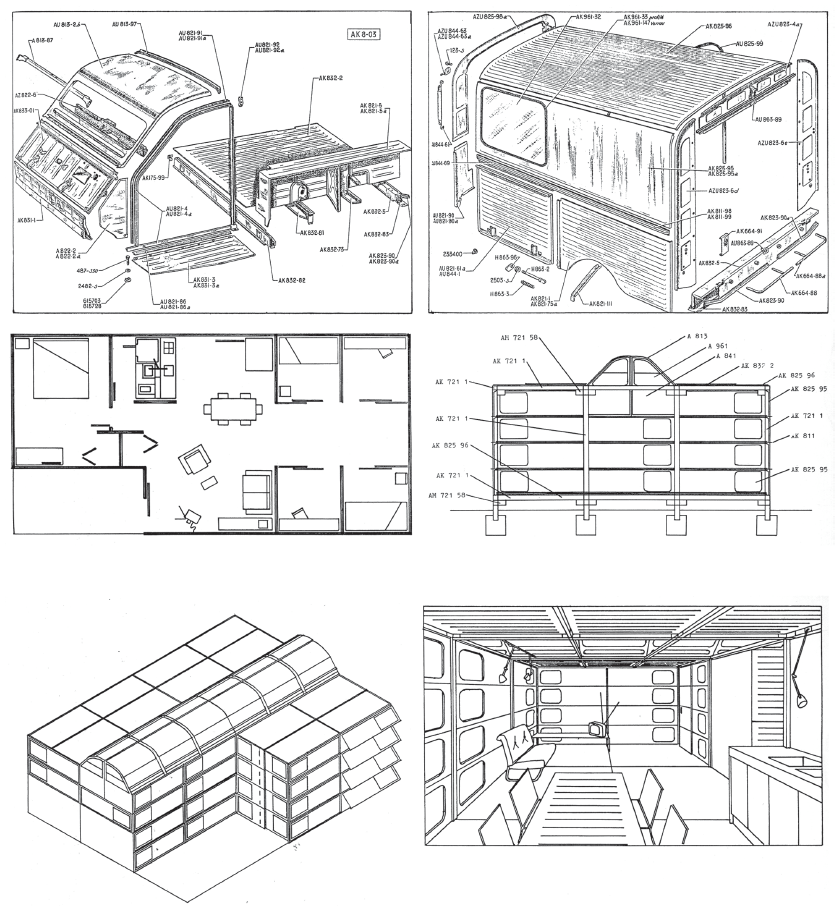

The project proposes a radical alternative approach to the renewal of Lilong neighbourhoods in central Shanghai. The proposal preserves the social network, lifestyle and collective memories of local Lilong communities, as opposed to the typical tabula-rasa approach that results in gentrification, displaces local communities, and deprives them of their lifestyle, social experience and the convenience of being in central Shanghai. Yong’an Fang, a Lilong settlement built in 1911 in the Bund area, is chosen as a pilot site.

By moving the community upwards into a structurally independent superstructure where each household retains the address and footprint of the property it once owned, protected existing buildings are freed for developments that will generate greater economic results. In the superstructure built to modern living standards, the lifestyle and social network of Lilong communities, shaped and sustained by public domesticity, are retained. Similar to traditional Lilong housing, communal areas in the superstructure are dispersed three-dimensionally throughout the neighbourhood and woven into the pores between private living quarters, blurring the boundaries between the public and the private. At the same time, the volumes of each living unit are significantly increased by exploiting loopholes in planning laws, where some spaces do not count towards the total floor area of a property.

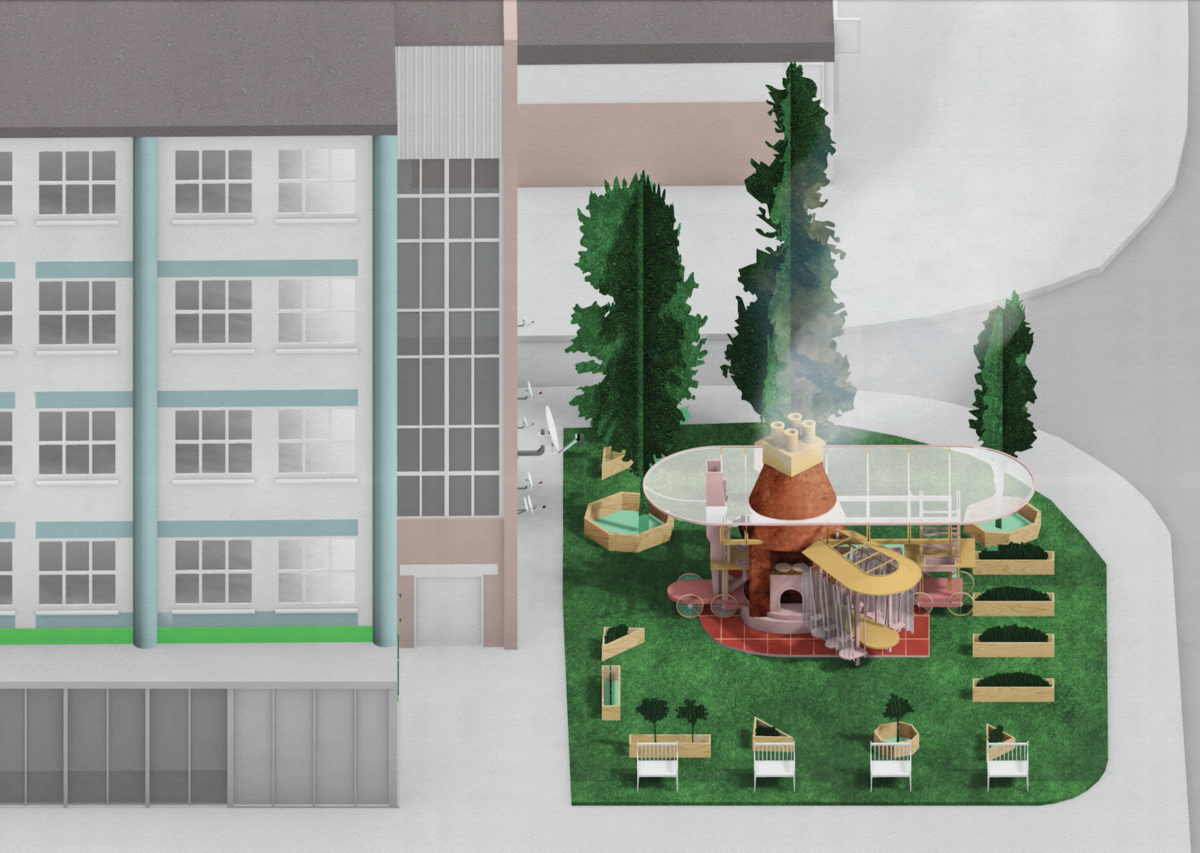

Bata’s Wild Regeneration

Bata’s Wild Regeneration aims to question our contract with nature, within the context of our relationship to the once natural landscape of East Tilbury, Essex. Through the industrialisation of the past 200 years, we have severed our rapport with nature, ignored its cyclical processes, and as an act of self-sabotage, abused the environments that benefit our health and well-being most. To reverse this damage, we must recognise the rights of nature, adhering to principles of permaculture to change the way we live, design and build.

Over two projects I hoped to explore how the design of space and the resourcing of materials can have a positive impact on the regeneration of the natural landscapes of East Tilbury. The first project, a wild swimming bathing house, focused on the regeneration of a pond habitat with a floating bathing machine that reacts to the ponds imbalances and fragility. The second project looks at the impact of our modern agriculture practices, questioning how the natural resources of East Tilbury would allow for a switch to regenerative styles of agriculture and minimalist co-living living, elevating the community whilst improving the health of the environment and its soil.

‘If design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design; if architecture is merely the codifying of the bourgeois models of ownership and society, then we must reject architecture; if architecture and town planning [are] merely the formalization of present unjust social divisions, then we must reject town planning and its cities […] until all design activities are aimed towards meeting primary needs.’

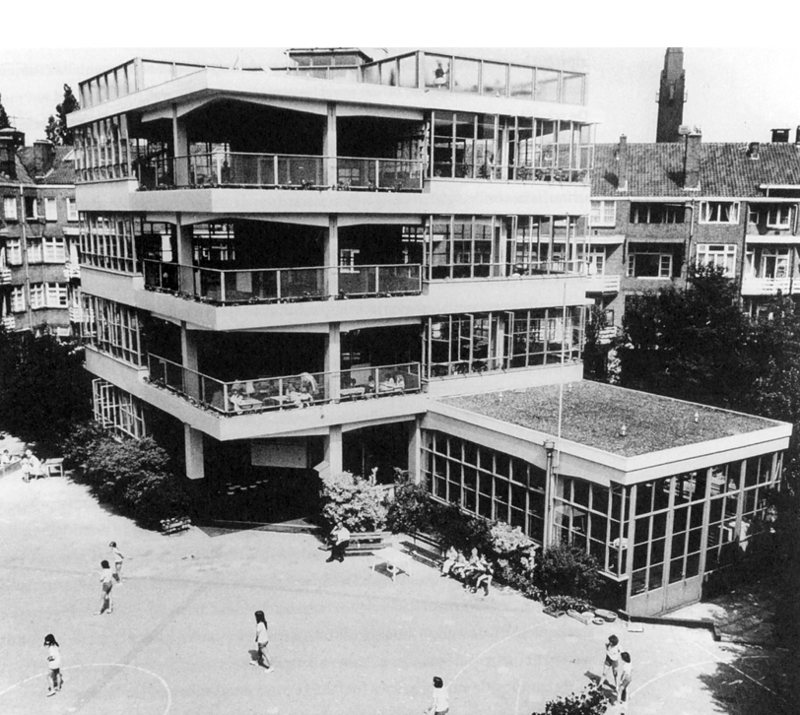

Built in 1927, the Open Air School in Amsterdam has been a new model for education at the beginning of the 20th Century.

The building consits of a series of open and enclosed terraces allowing children to be educated in the open air.

Amazingly the shcool is still operating.

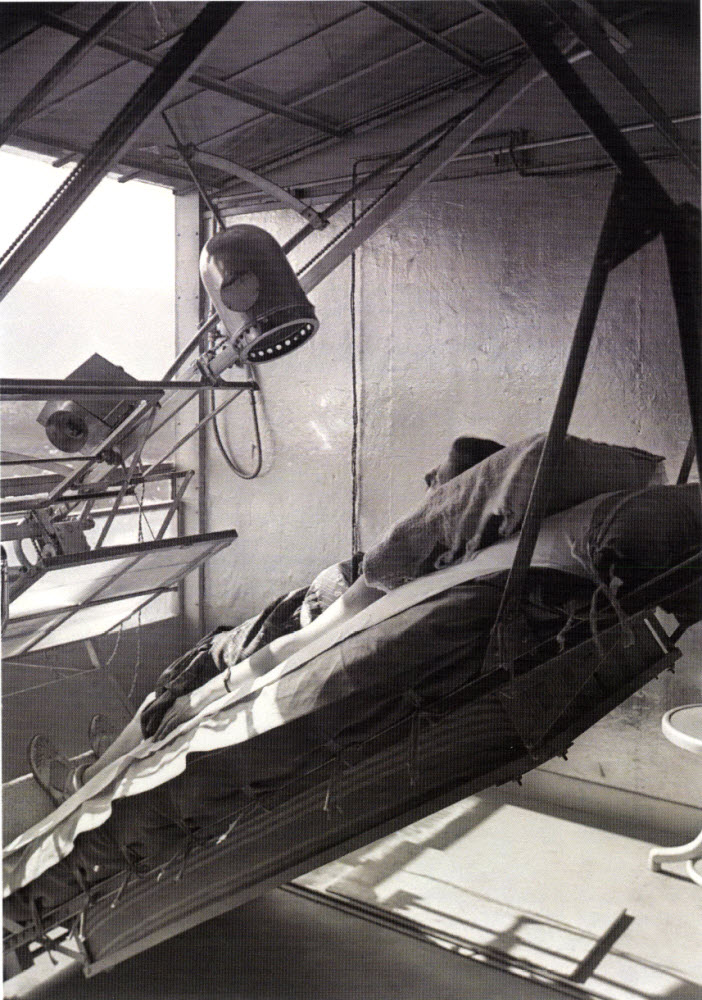

The French radiologist Dr. Jean Saidman invented the revolving sanatorium. Build 1930 in Aix-les-Baines in France the whole structure revollved to allow patients facing constant exposure to the sun. Thsi was an attempt to cure them of tuberculosis and rickets.

Sweet Water Organics, a company in Milwaukee, raises perch and grows leafy green vegetables in a former factory.

Urban Sweet Water Organics launched in Milwaukee in 2009 combining growing green vegetables with raising fish. The fish lives off the waste products off the plants and the plants grow on the fish waste.

THis circular system uses 90% less water compared to traditional fish farming while producing hundreds o kilograms of vegetables and fish in a closed system.

The destruction of our environment through intensive farming – both on land and in the water – has left vast areas of our environment stripped of biodiversity, oversaturated with fertilizers, ruined by pestizides.

Sweet Water Organics – Milwaukee

Recycling seems to have finally become mainstream – thanks god for that! But it hasn’t always been like that. The throwaway culture started a long time ago and it seems some visionaries have seen the writing on the wall long before the rest of us has caught up to this.

One of these visionaries has been Martin Pawley, a british architect who promoted his ideas for the garbage housing as early as 1975.

Nowadays we all talk about recycling, how we should avoid creating more and more waste to pollute our planet.

The designer Aino Aalto resting on a lounge chair on the solarium terrace of the Paimio Sanatorium in 1932. Photo taken by Alvar Aalto.

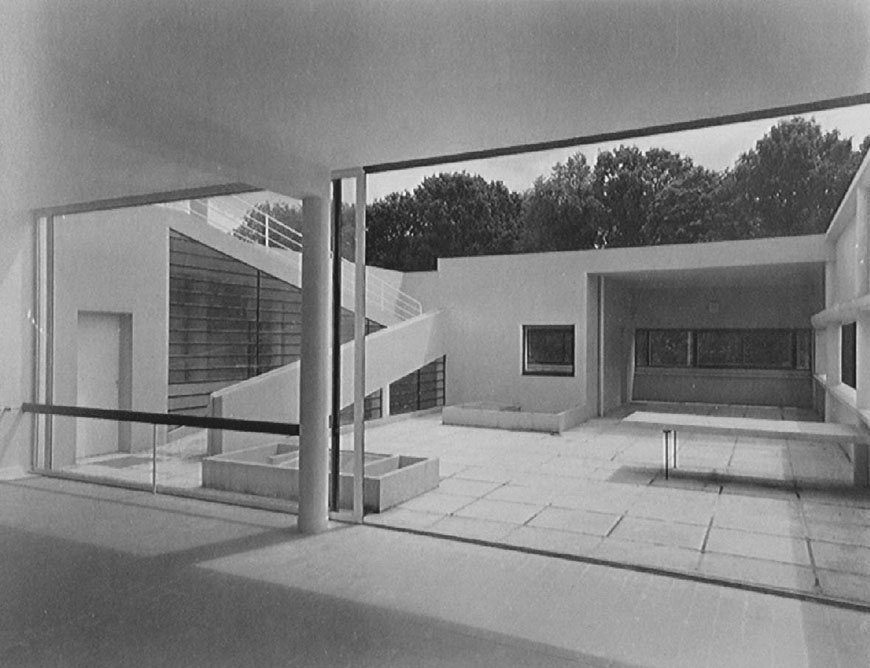

In the 1920-1930 a new movement in architecture emerged from Europe. Modernism promoted an architecture that was characterised by its clean lines and white walls. Functional spaces that were pure and free of any decoration or ornamentation associated with historical architecture.

But on closer inspection this new movement was not about style, about dismissing the architecture of the past on aestetic or purely formal grounds. It has much deeper roots in the desire to eradicate tuberculosis, a disease that, at the time, didn’t have a medical cure.

Robert Koch discovered the tuberculosis bacillus in 1882 but until 1949 there wasn’t an effective medical treatment for this disease. It had been understood that the disease spread and was dormant over long periods of time, hidden the dust of the houses with a poor ventilation aggravating the situation. In 1900 tuberculosis was responsible for 25 percent of all deaths in New York.

Modernism must be seen as a reaction to this crisis. At the time the only real cure for the disease was what was called the Freiluftkur, where a person was treated with plenty of fresh air, lots of sunlight, and nutritious food. The standard ‘cure’ for TB was primarily a change of the environmental conditions. Very soon architects responded to the challenge by devising an architecture that was dominated by clean lines (that were easy to be cleaned), surfaces free of ornamentation (trapping dust and spreading the disease). Buildings were elevated off the ground (to allow air to circulate and to remove the inhabitant from the damp ground), walls were penetrated with large windows (allowing in sunlight and fresh air). These building were not machines for living, they were machines for healing.

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoy, Paris, 1929

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoy, Paris, 1929 Open airy spaces, light flooding into the living spaces.

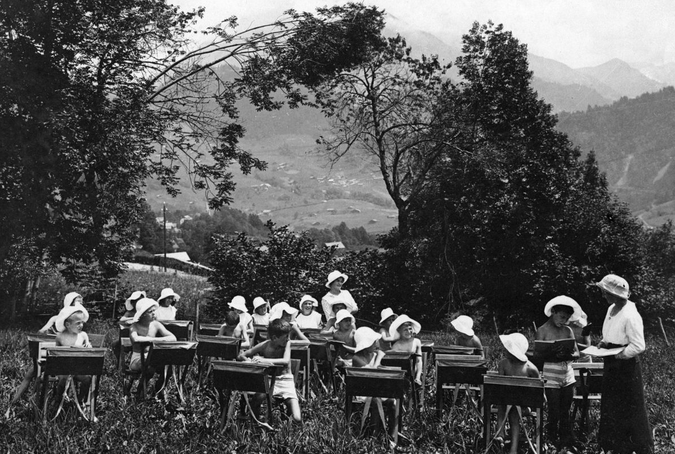

Children being taught in the open air, ca. 1920

Jan Duiker, Open Air School, Amsterdam, 1927

x