Category: 2019

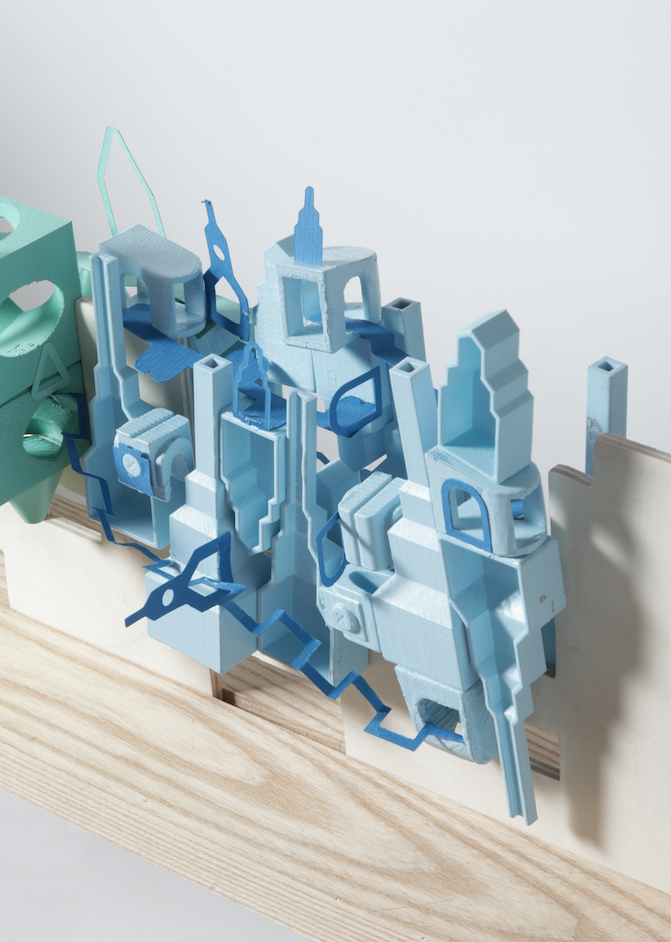

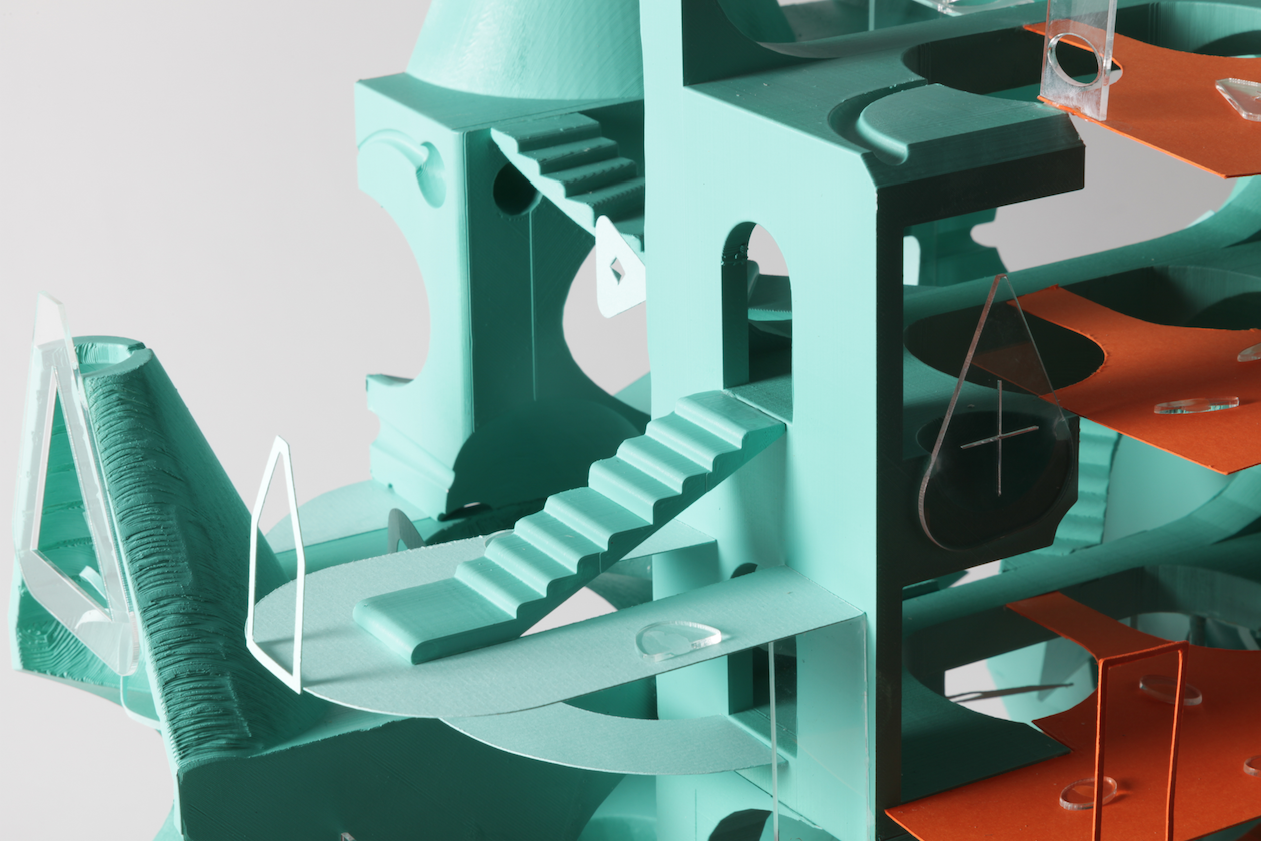

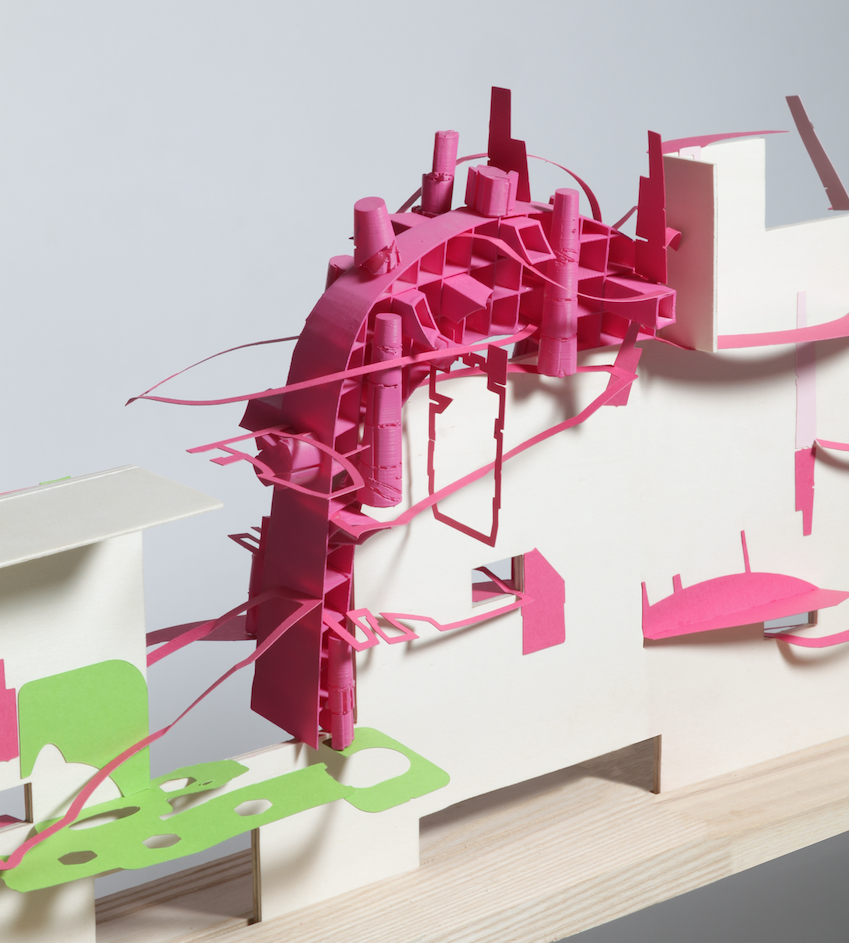

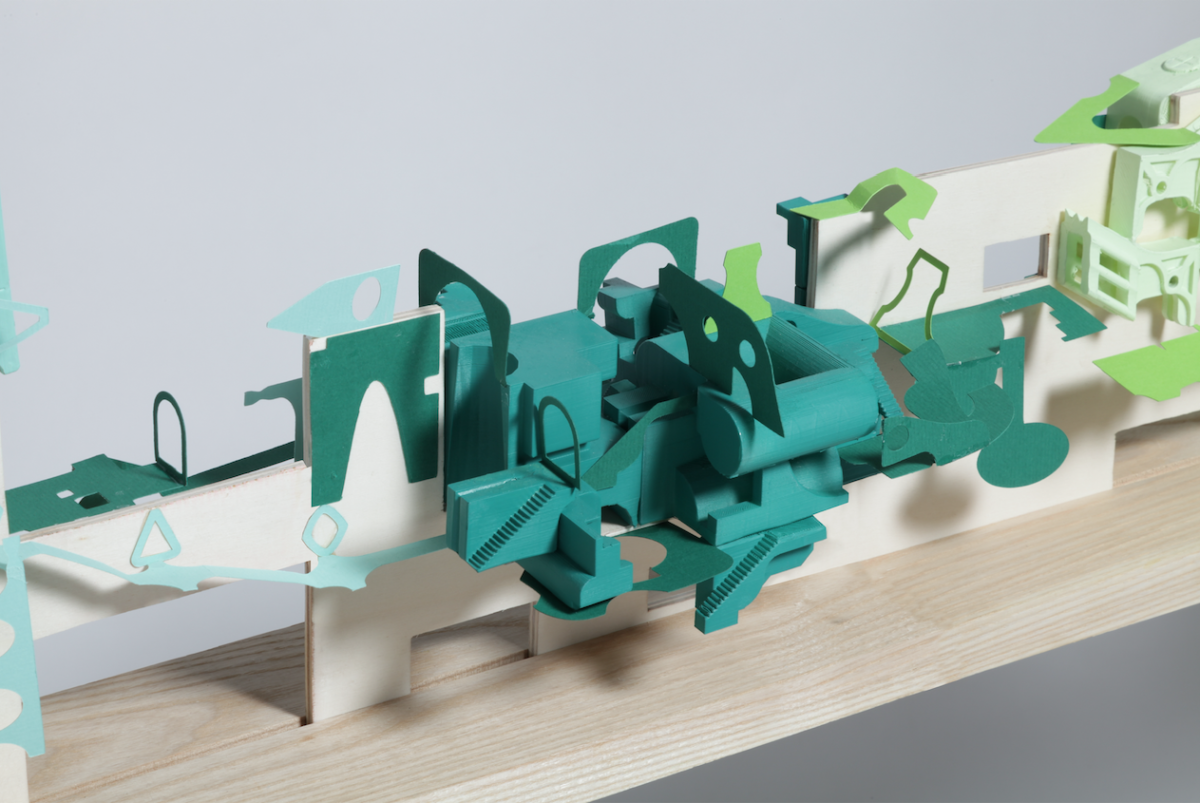

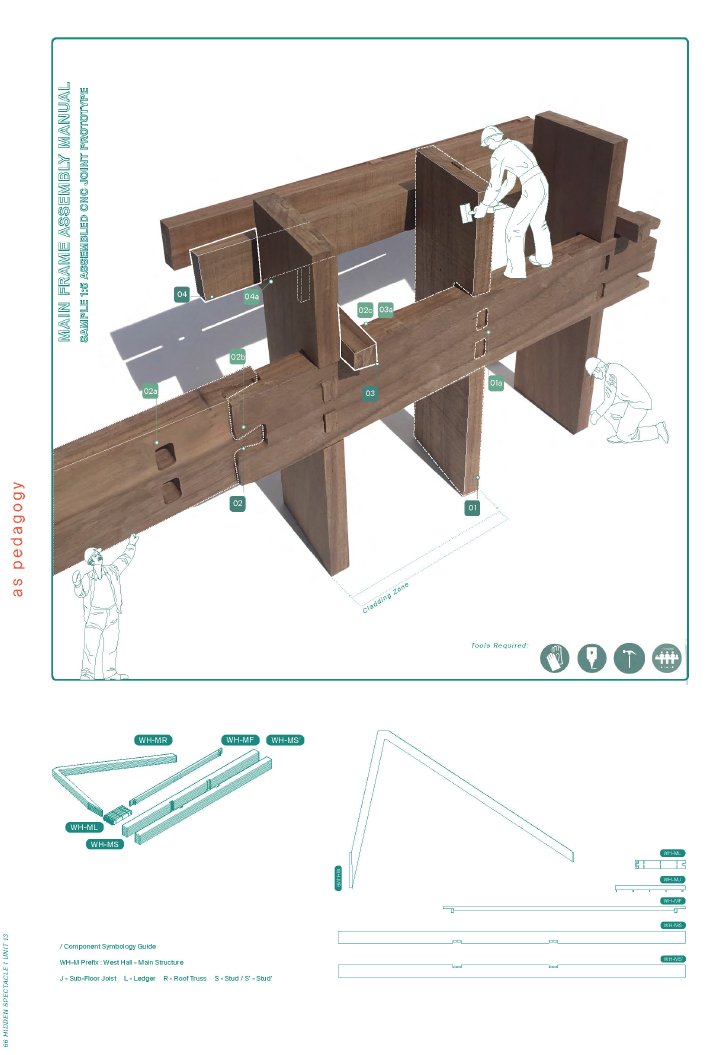

PG13_Hidden Spectacles

The ‘Back of House’ Atlas for new Models of Inhabitation

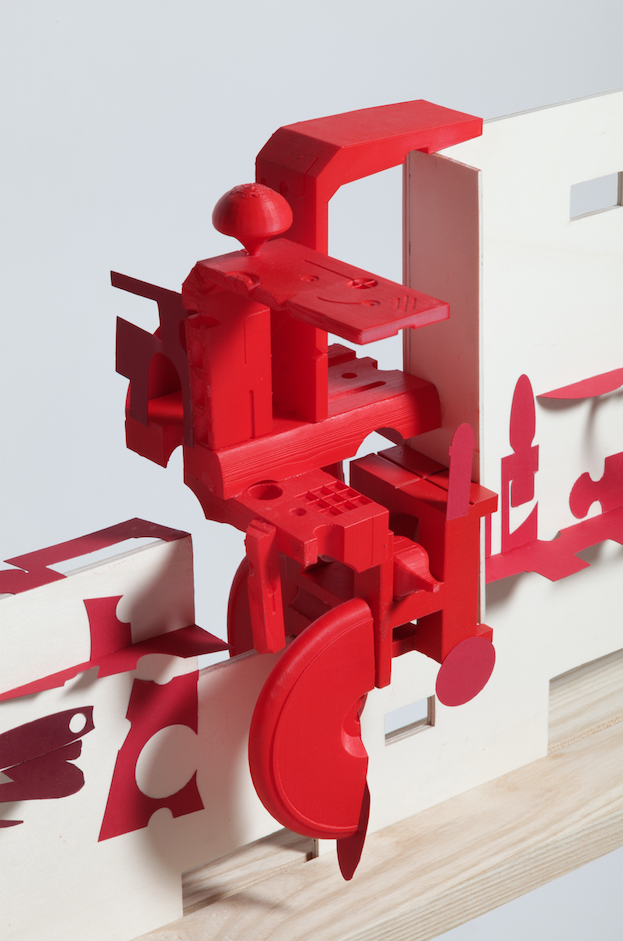

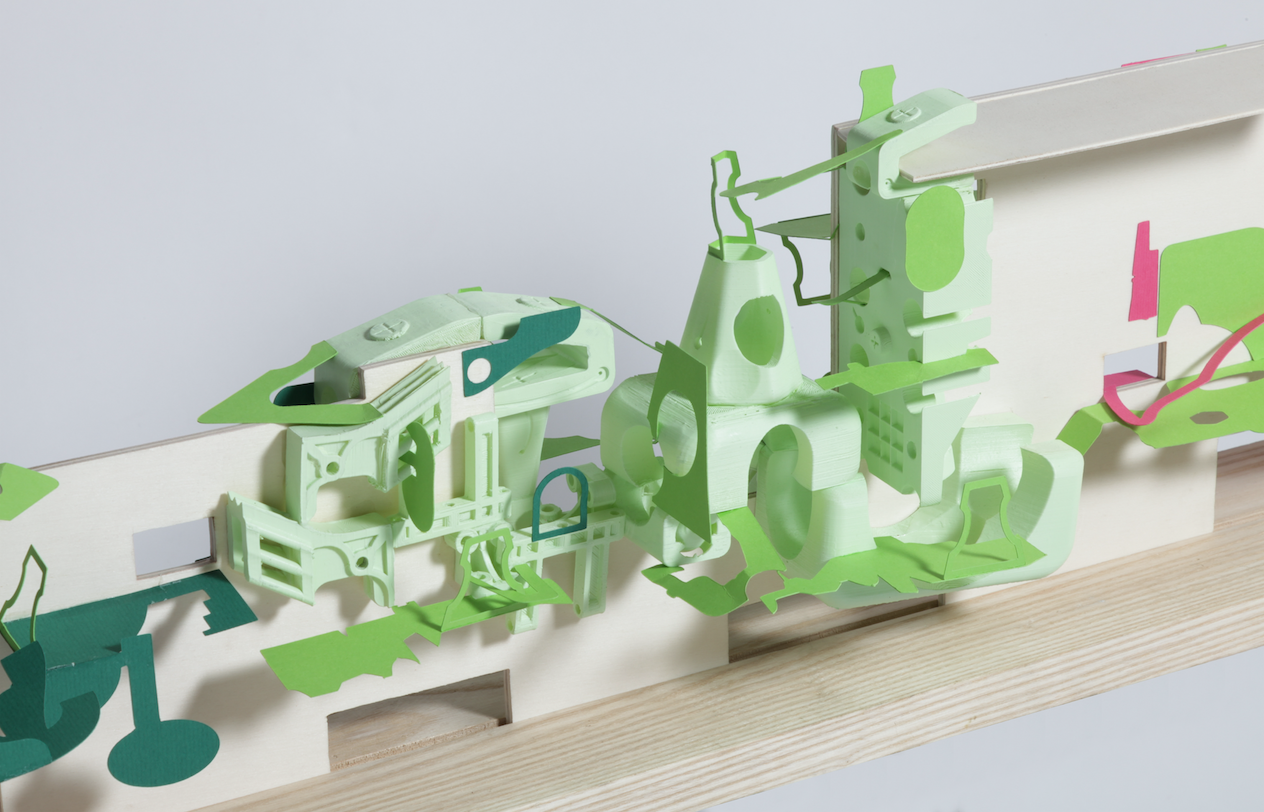

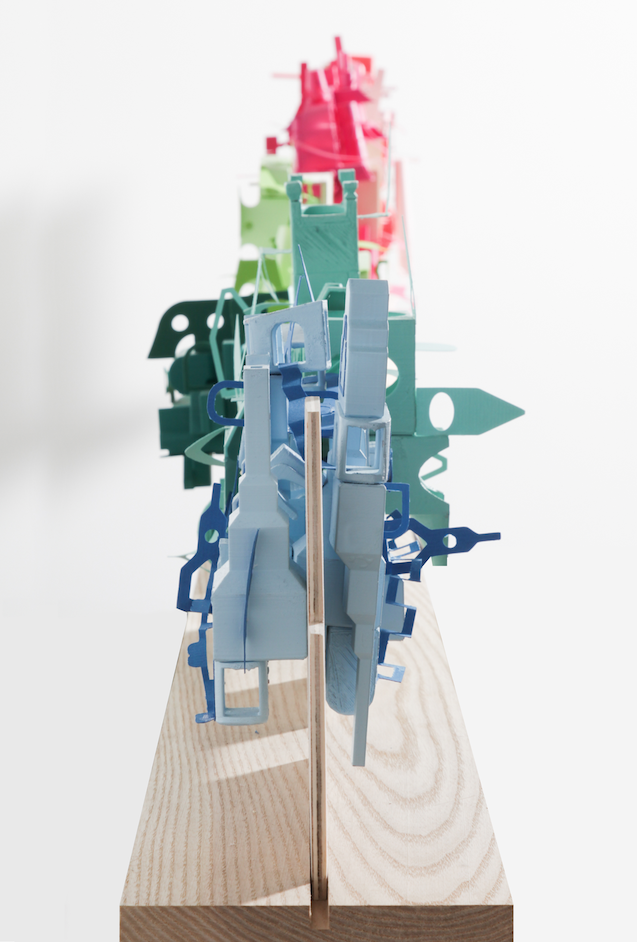

Spectacles are amazing events and scenes or displays. Our HIDDEN SPECTACLE will explore the nature of a different kind of spectacle – the inner workings of a place, the way things are worked out, when the back of house becomes actually the front of house, the place where new models are tested, and innovations are made.

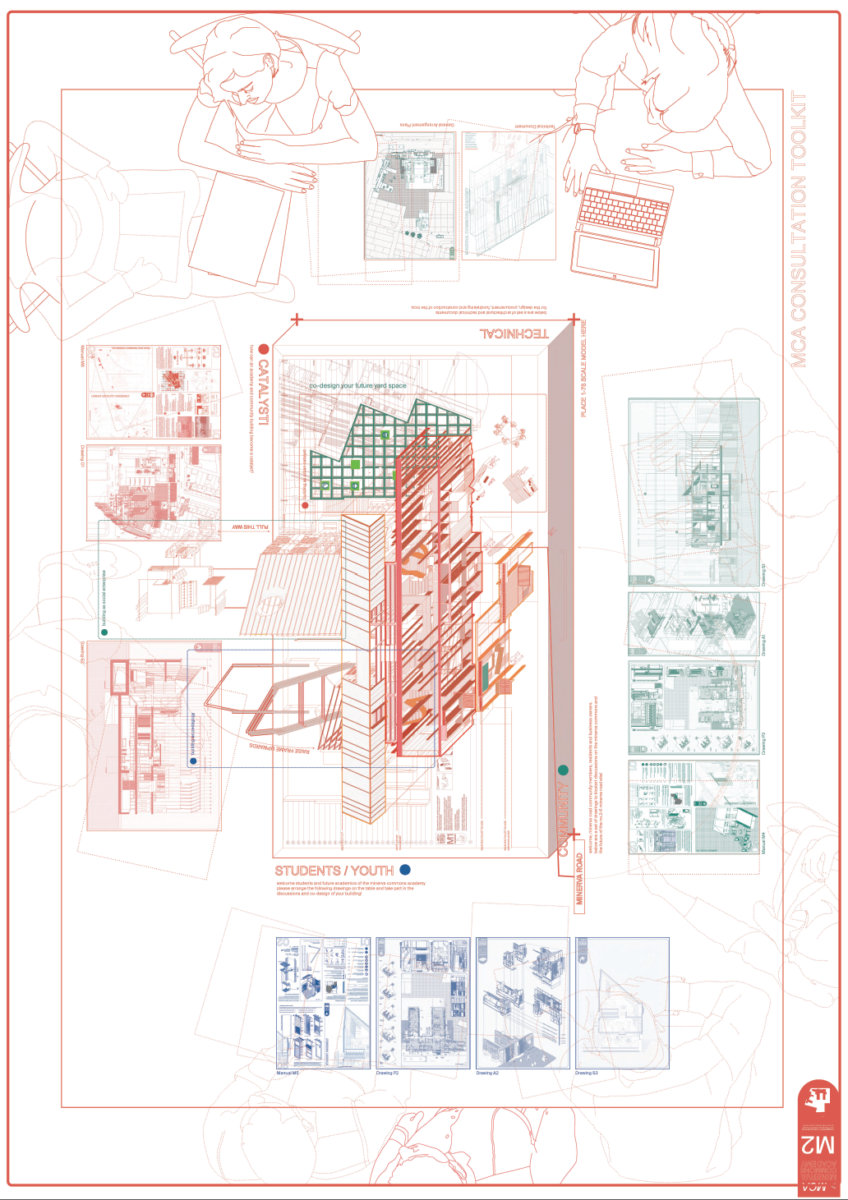

Unit 13 is continuing the journey to explore the city and invent new models of inhabitation for the future in our LIVING LABORATORY. Our interest lies in the careful observation of communities, the challenging of the regulatory frameworks, design research and innovation and to imagine a speculative part of the city set within a real context. They for the testing ground for the interdisciplinary cooperation between the different stakeholders. These new methodologies create the conditions to make the city more liveable presenting an alternative concept of living and working on the fringes of the city.

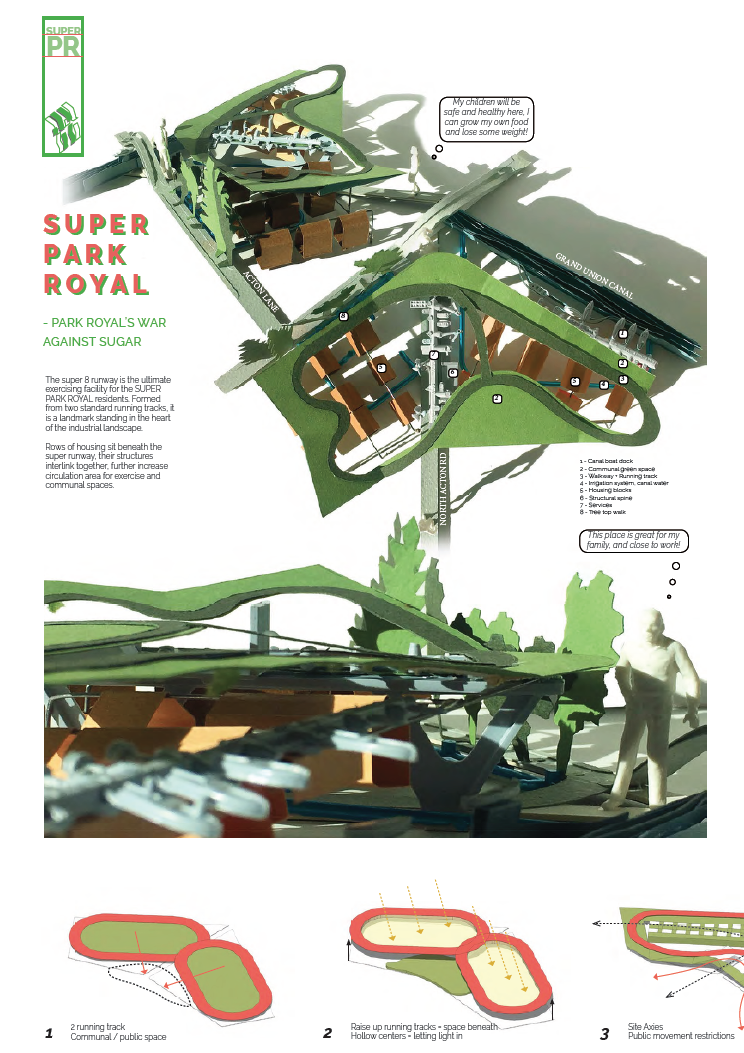

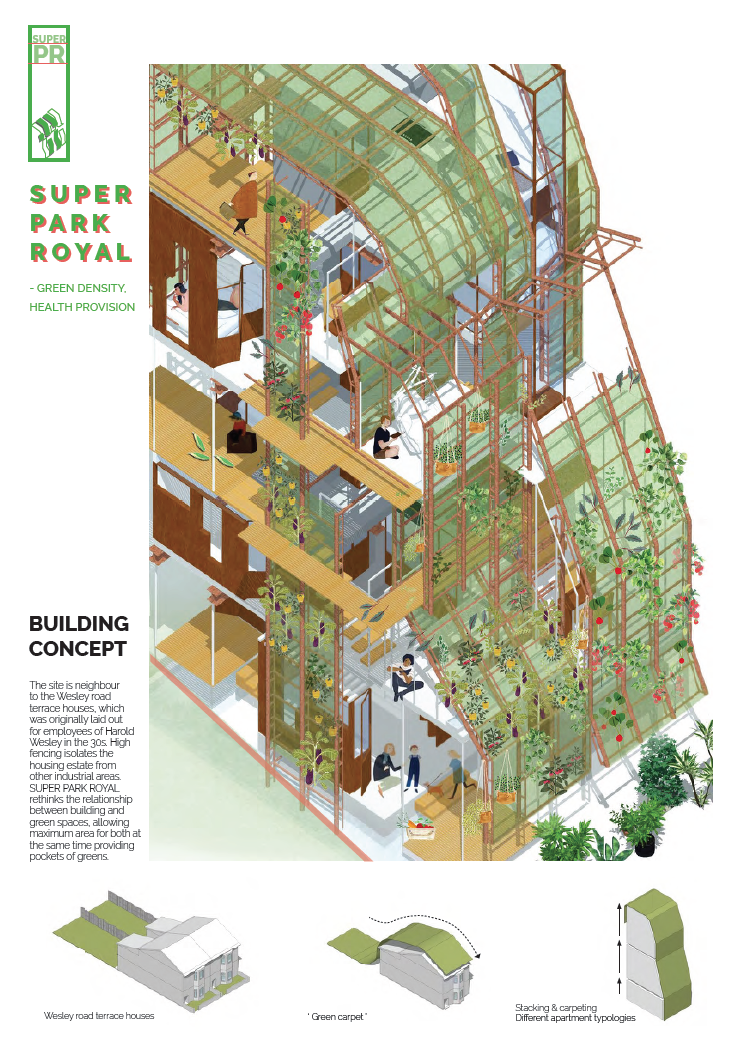

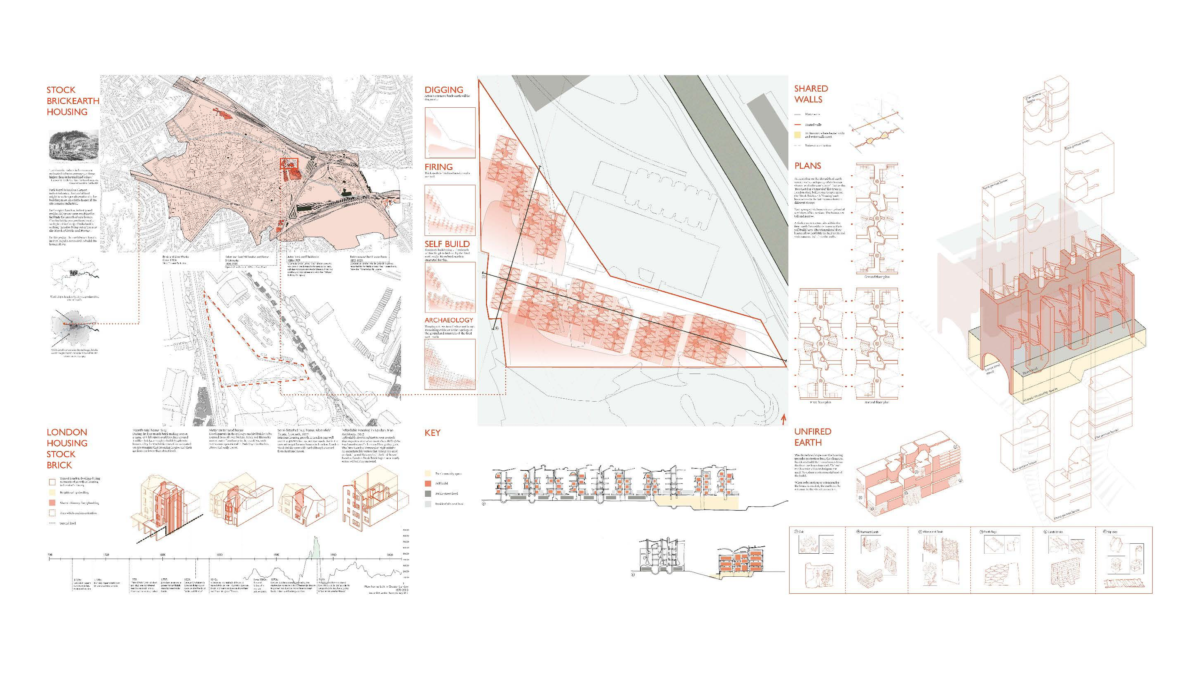

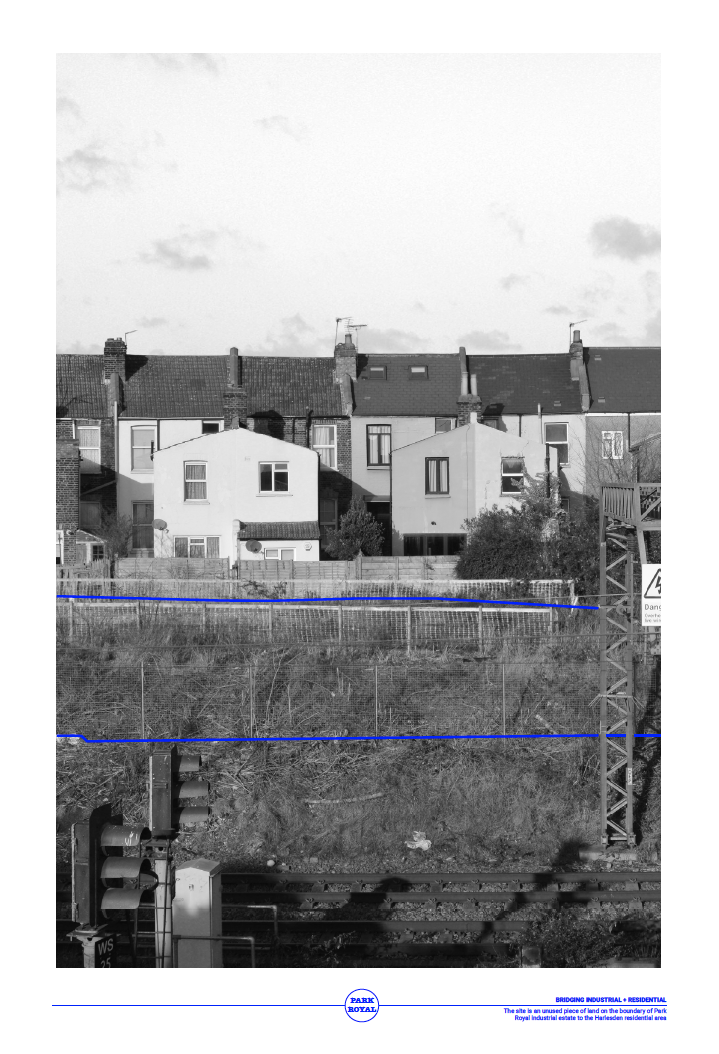

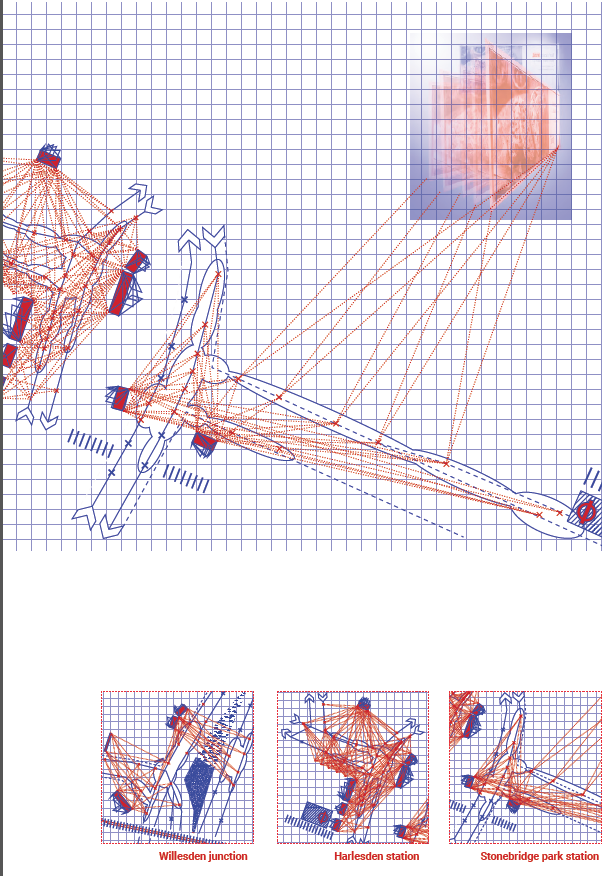

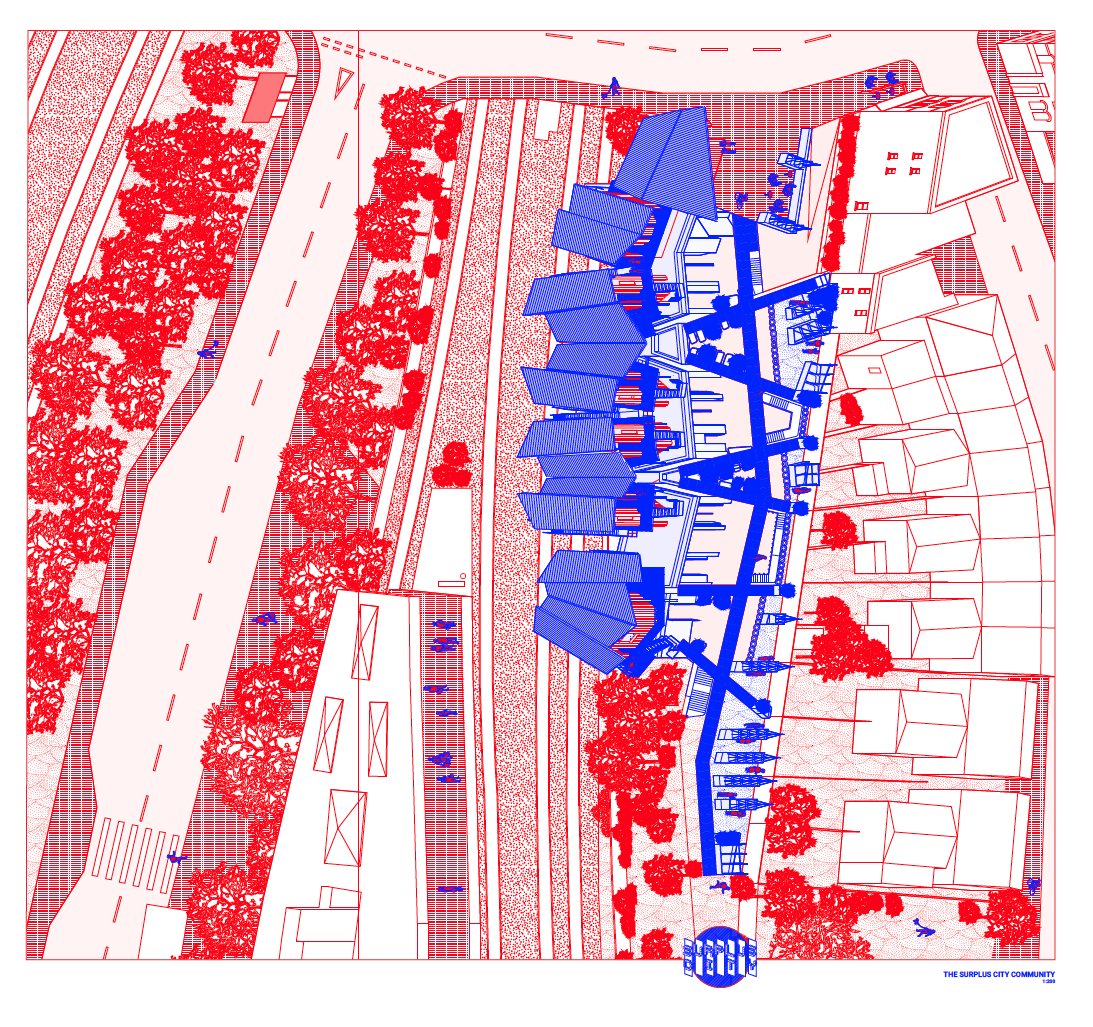

Over the last three years we explored Essex, devising new habitats and living models set within the post -industrial landscapes of London’s Greenbelt. This year we will explore another area on the fringes of London. PARK ROYAL is one of Europe’s biggest industrial estate in the West London. Stretching over three boroughs it is equivalent to the size of the City of London. Being home to over 1,700 businesses and employing over 31,000 people. There are pockets of housing within the area but currently only around 4,000 people live within residential enclaves on the estate.

Unit 13 has been looking at this particular site located in West London. Having its roots as the Royal Agricultural Society Show grounds it is nowadays a diverse industrial estate where over 1,700 firms are operating from. Park Royal has been described as the kitchen of London. It is said 30% of all food for London is processed in the area. Being just outside the Old Oak Common development it will be subject to some big changes. 25,500 new homes and 65,000 new jobs in close proximity to our site will transform the area and have the potential to disrupt and create an alternative hub for new ways of living and working.

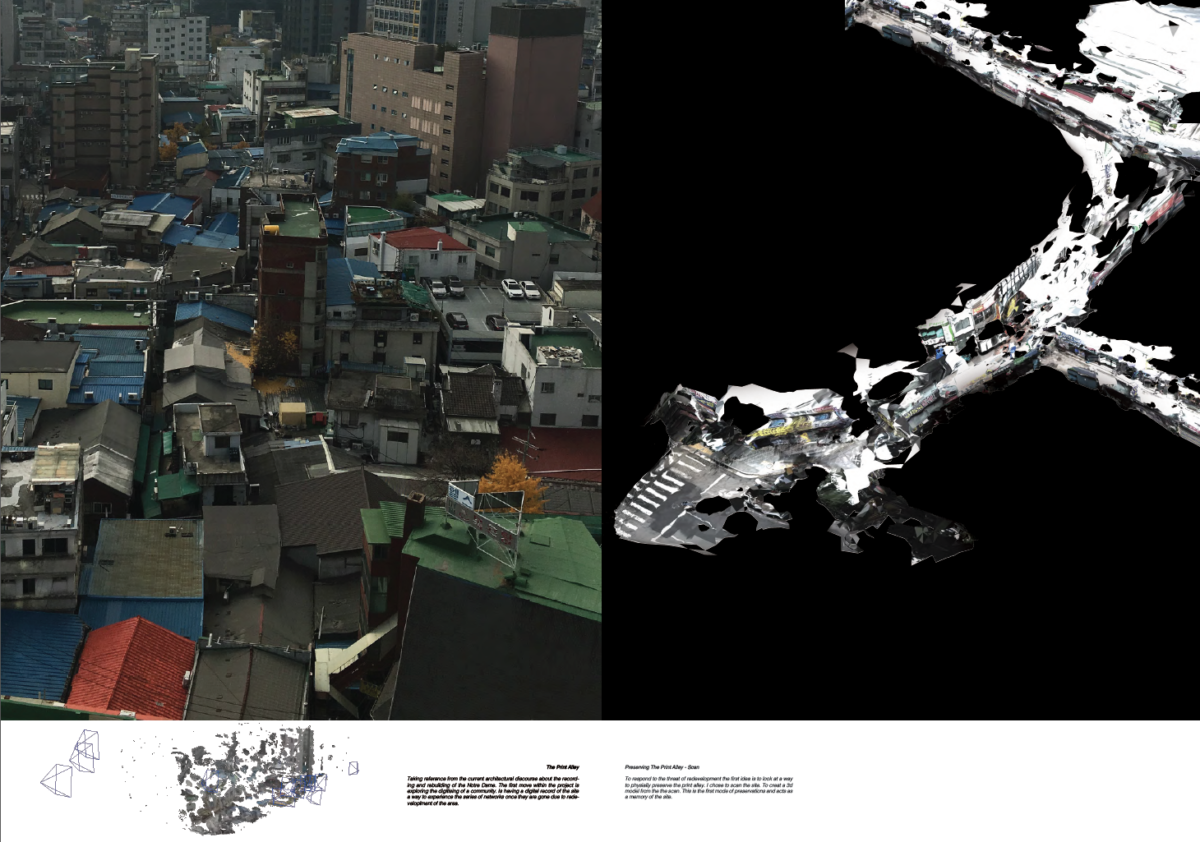

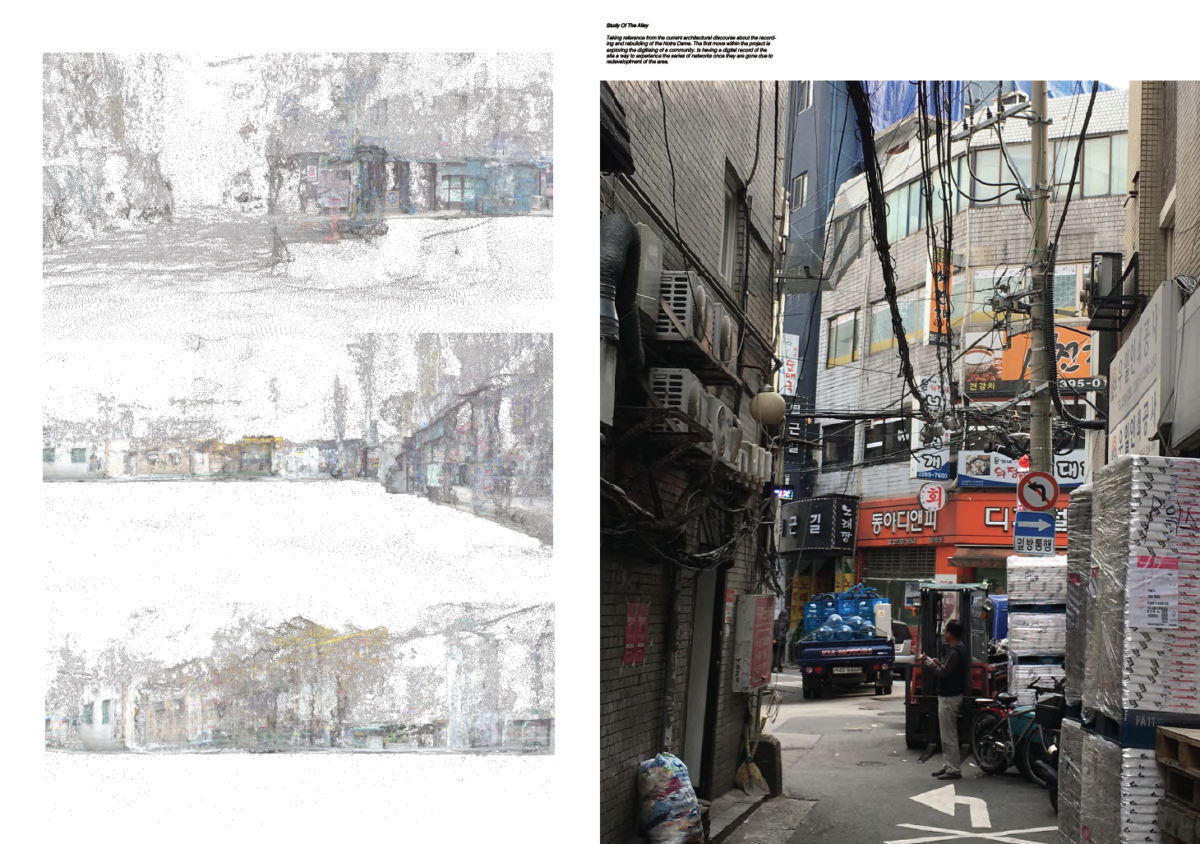

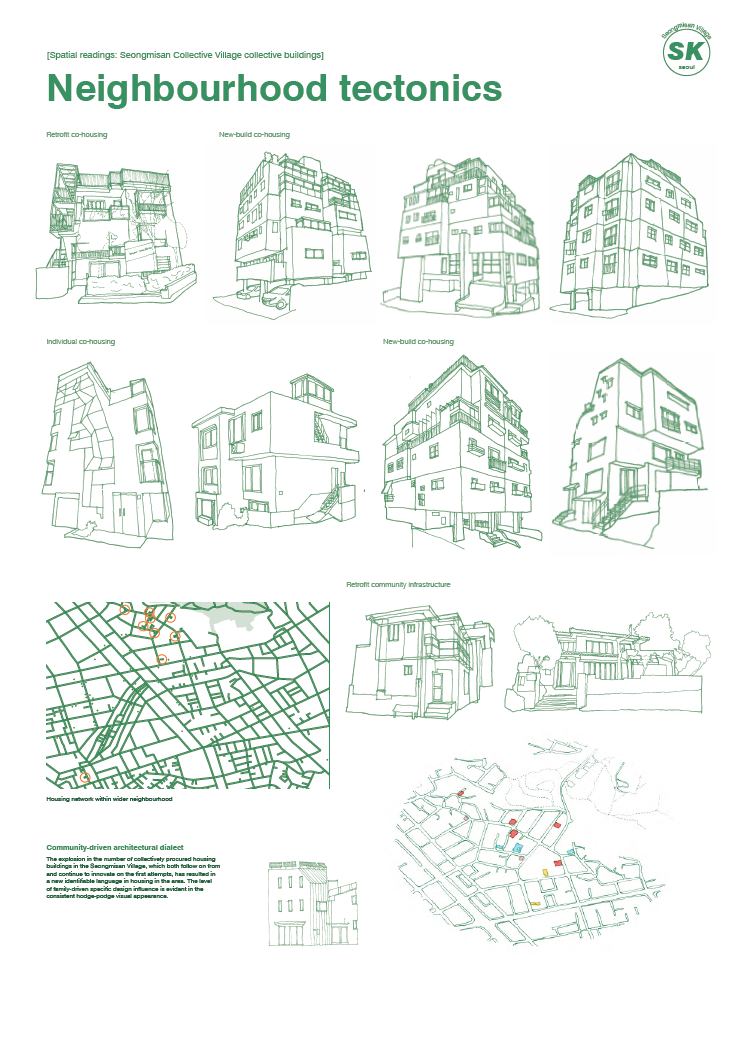

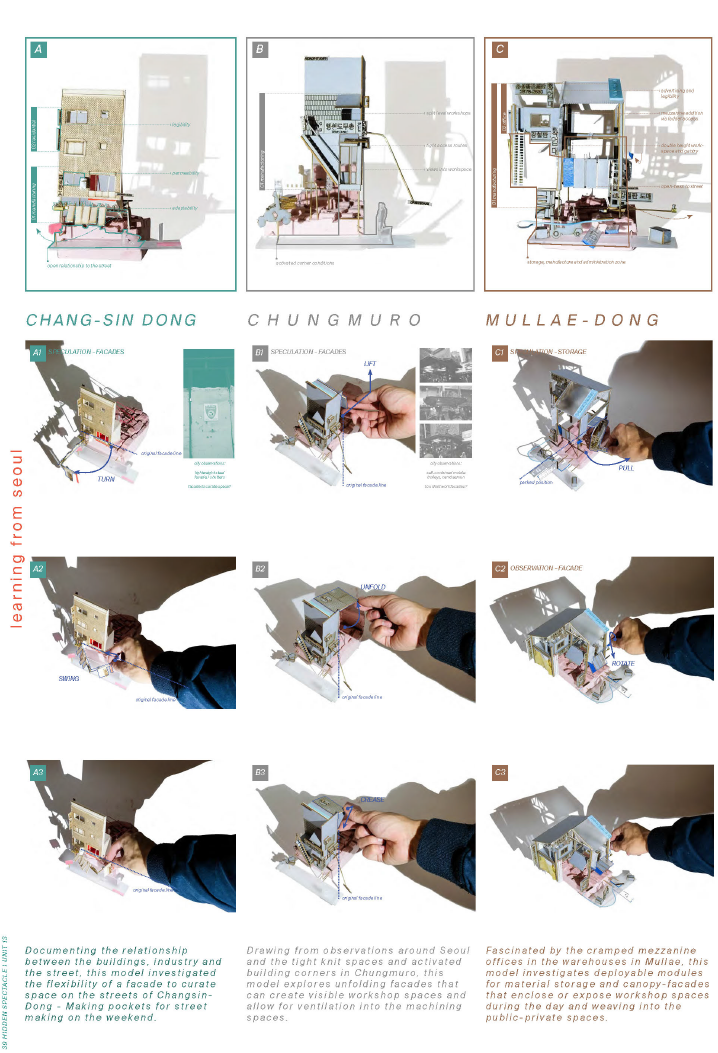

Unit 13 travelled to SEOUL in South Korea to explore the diverse fabric of the city. Our students explored the Back-of-House of Seoul. The parallels and contrasts with Seoul are fascinating – particularly looked at through the lens of production within the city. We worked with the Hanyang University and the University of Seoul for a collaborative workshop.

Seoul has some new emerging making districts within the city – printing, garments, food production etc – are most enjoyable places to visit. But in Seoul most of these activities are openly visible, they are part of the urban fabric, operating on a human scale they are interwoven with living and housing. Changes to demands can be answered much more quickly, changes to personal living conditions and styles are transferred rapidly to avoid unnecessary disruptions to the productive lives of the inhabitants.

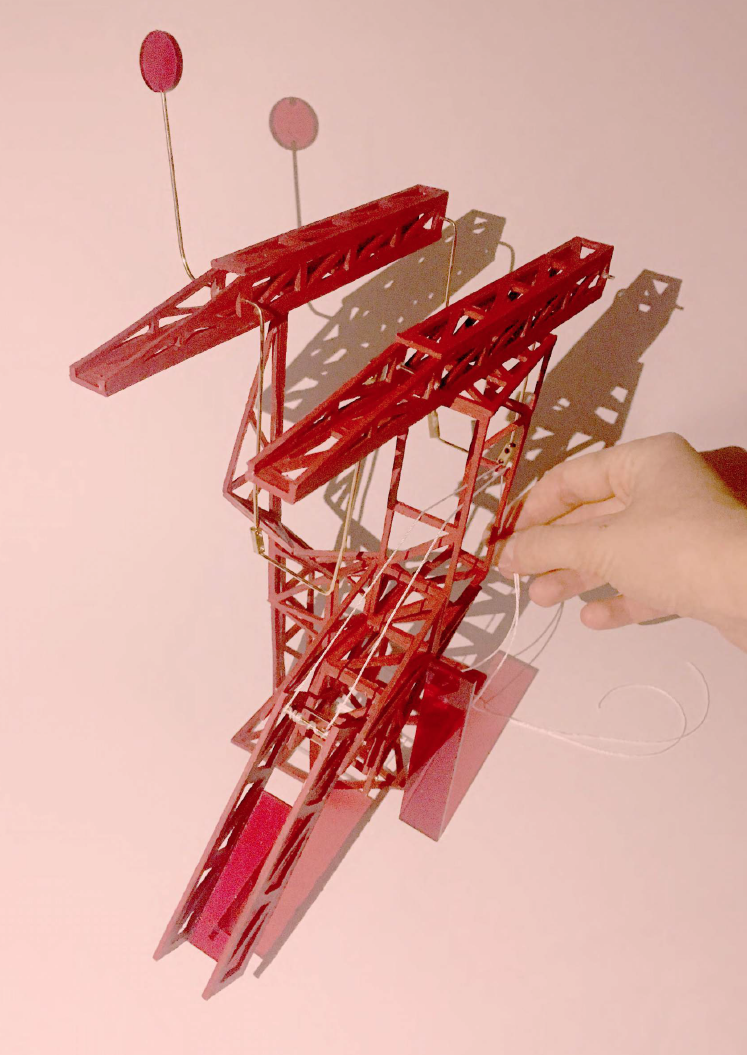

Unit 13 proposes creative new ways to inhabit the city. Our students develop diverse spatial scenarios. We envisage that a new culture of sharing within urban communities is paramount to the future of sustainable cities. Park Royal has been our testbed to explore these ideas for the year 4 DR and Seoul for the Year 5 design. Some of the key terms formed a departure point will be the Sharing City, Urban hacking, Re-acting, Collective, Community, Trans-ient and Trans-loci.

We aren’t interested in devising an iconic piece of architecture, we are interested in the moment inhabitation, interaction, production, fabrication etc. are turning a place or an architecture into a spectacle.

We don’t have any answers for you, just more questions.

DR tutor Rae Whittow-Williams

Technical consultant Toby Ronalds, EOC Engineers

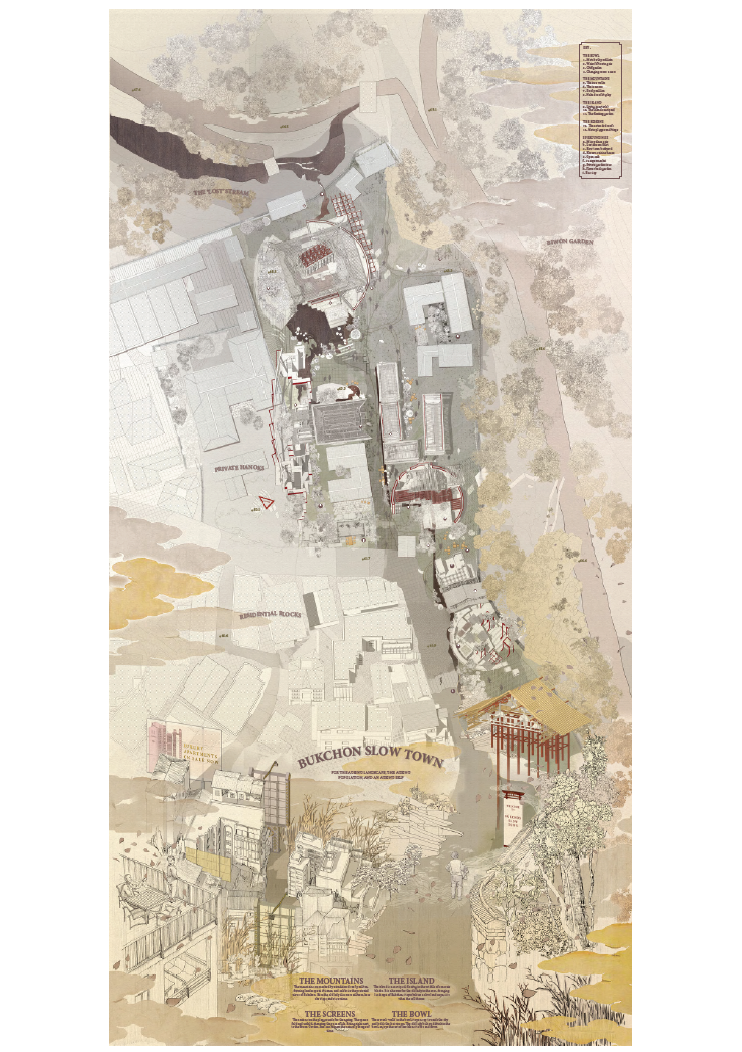

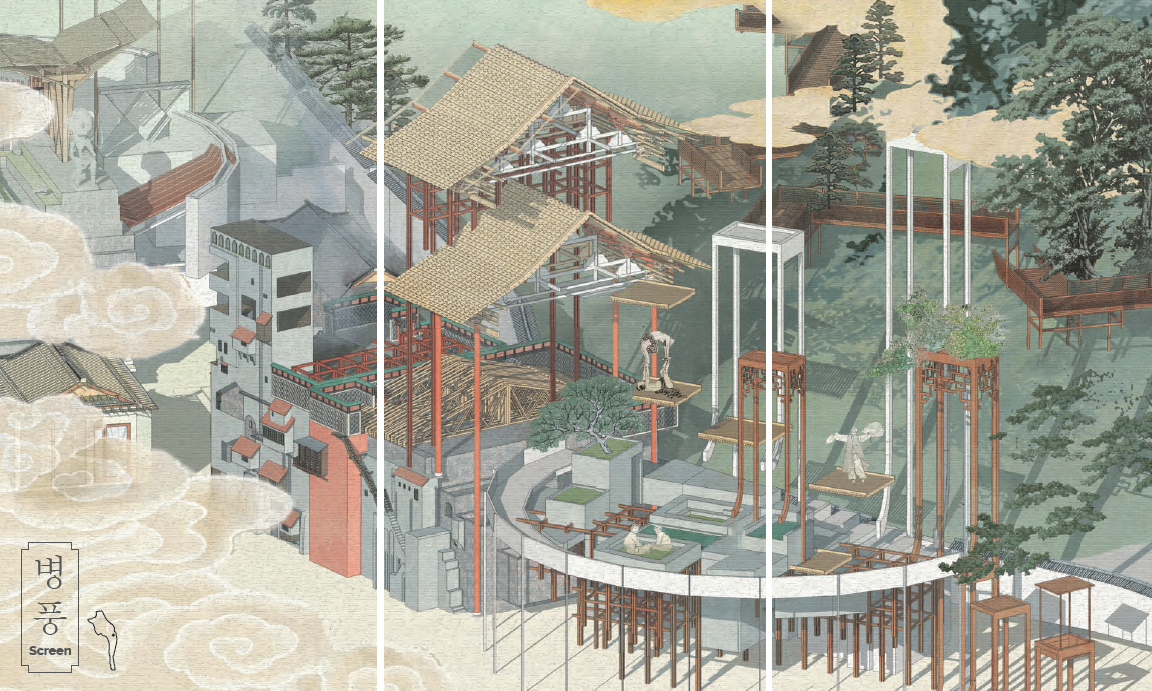

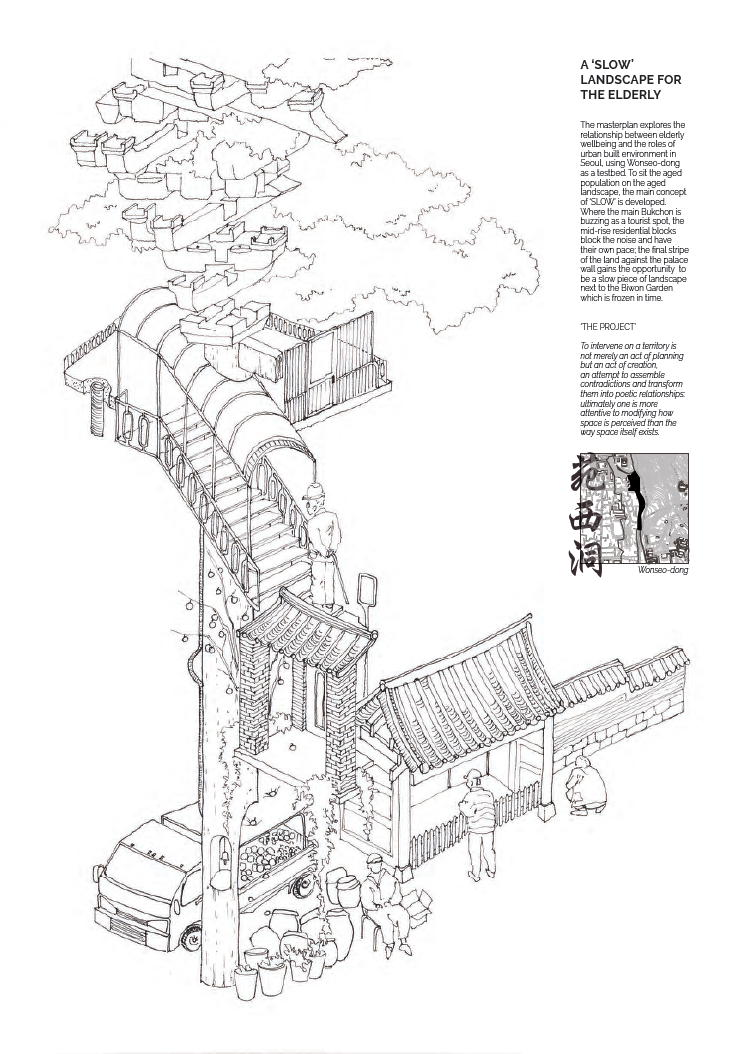

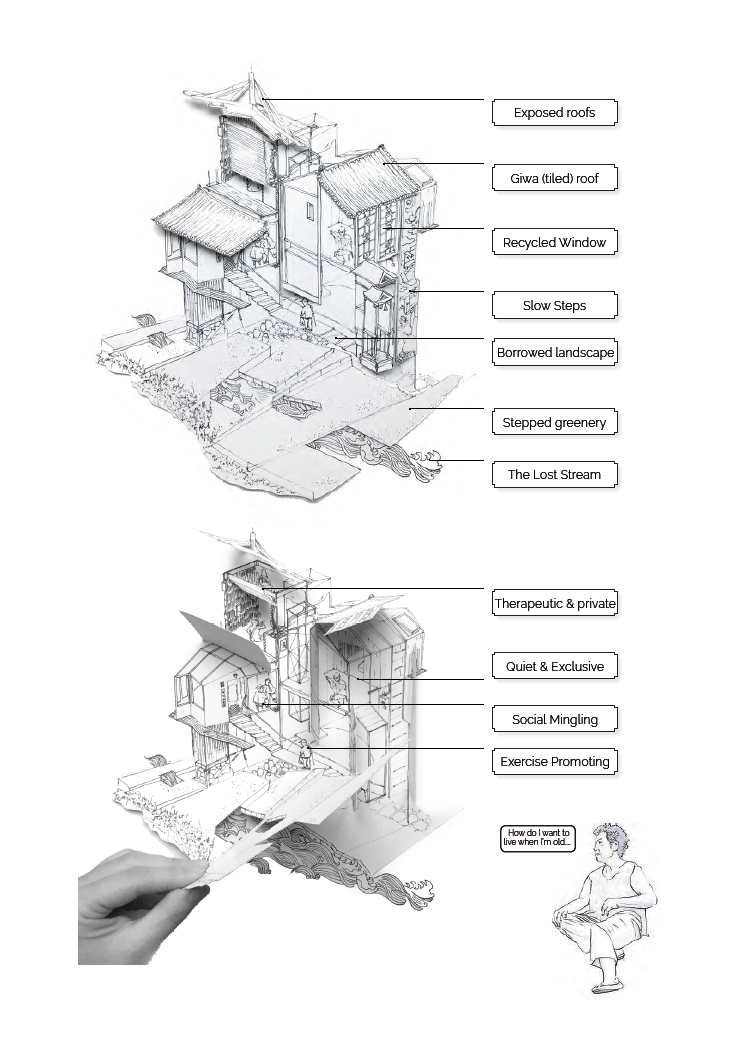

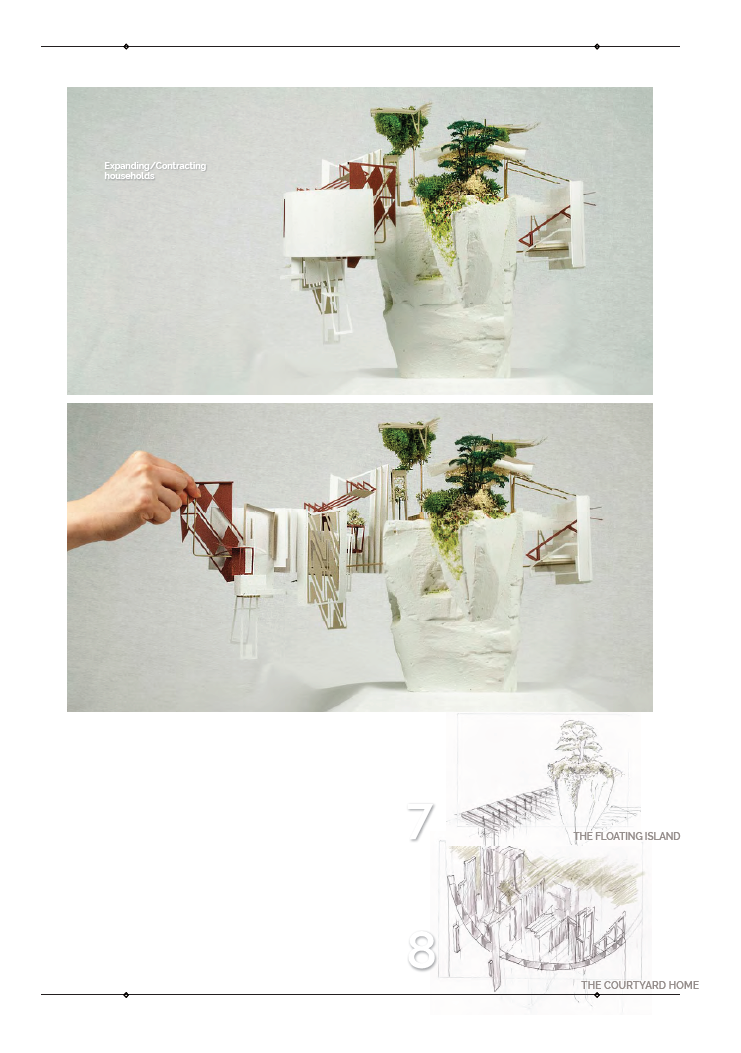

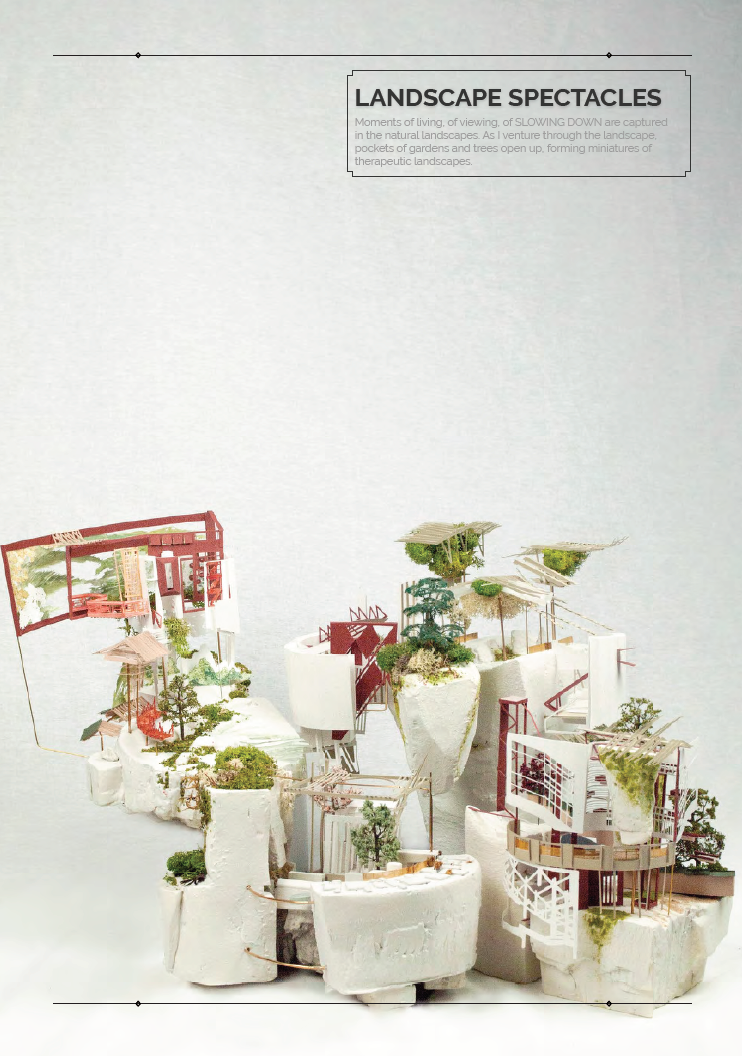

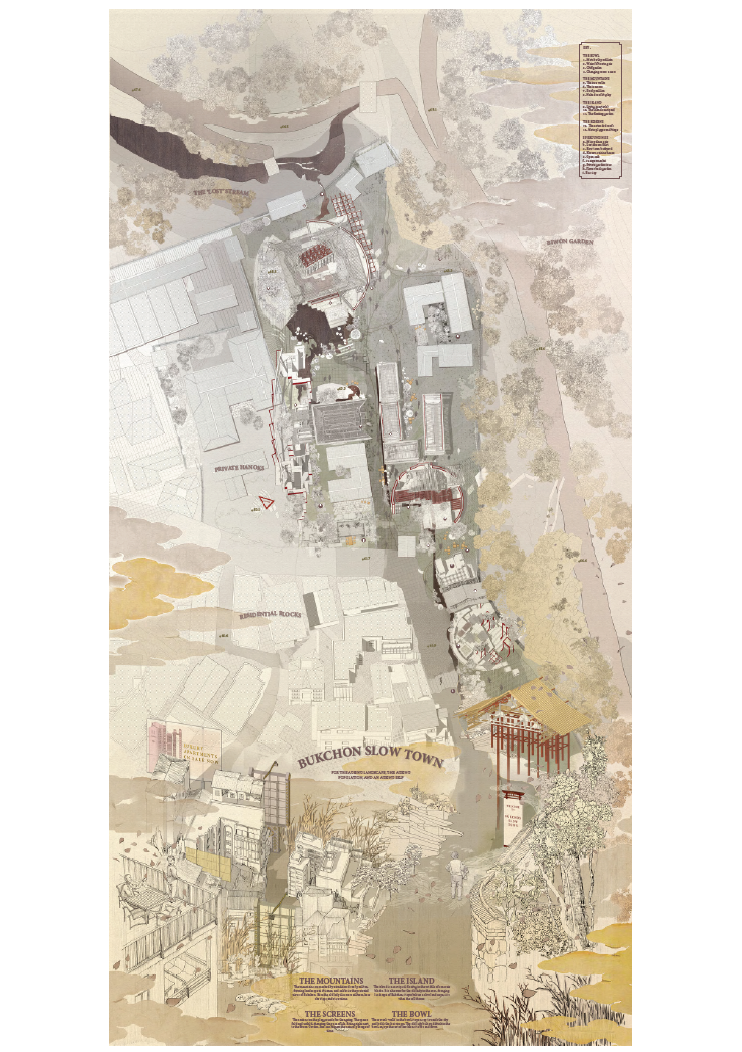

Bucheon Slow Town

An urban island for an ageing population

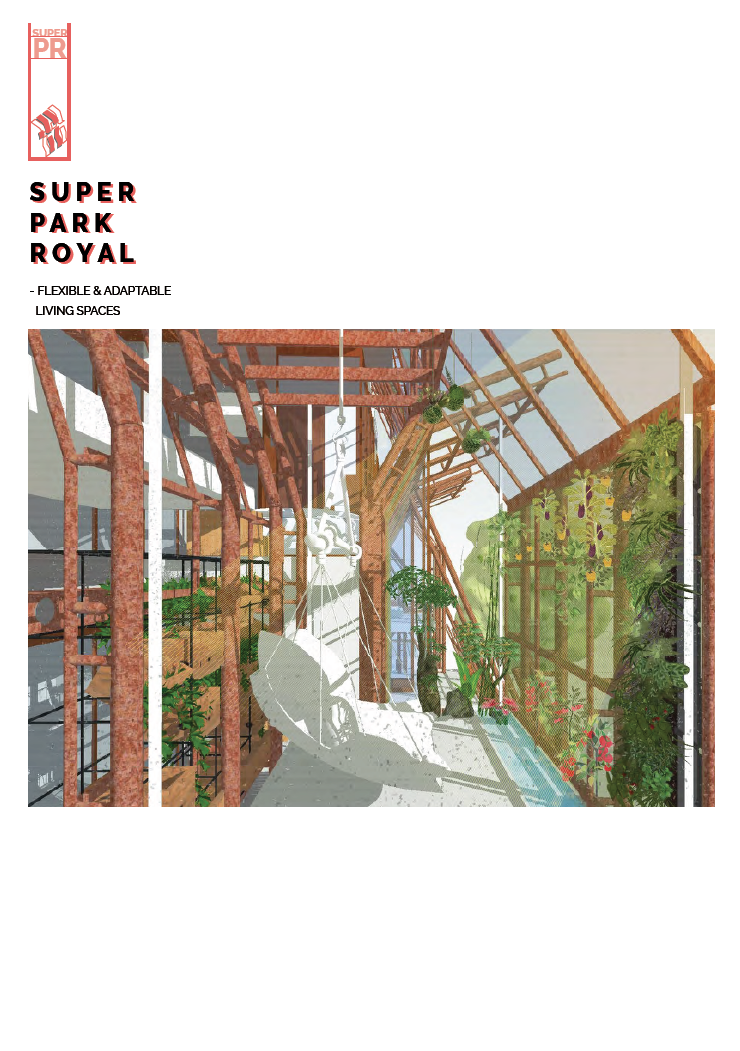

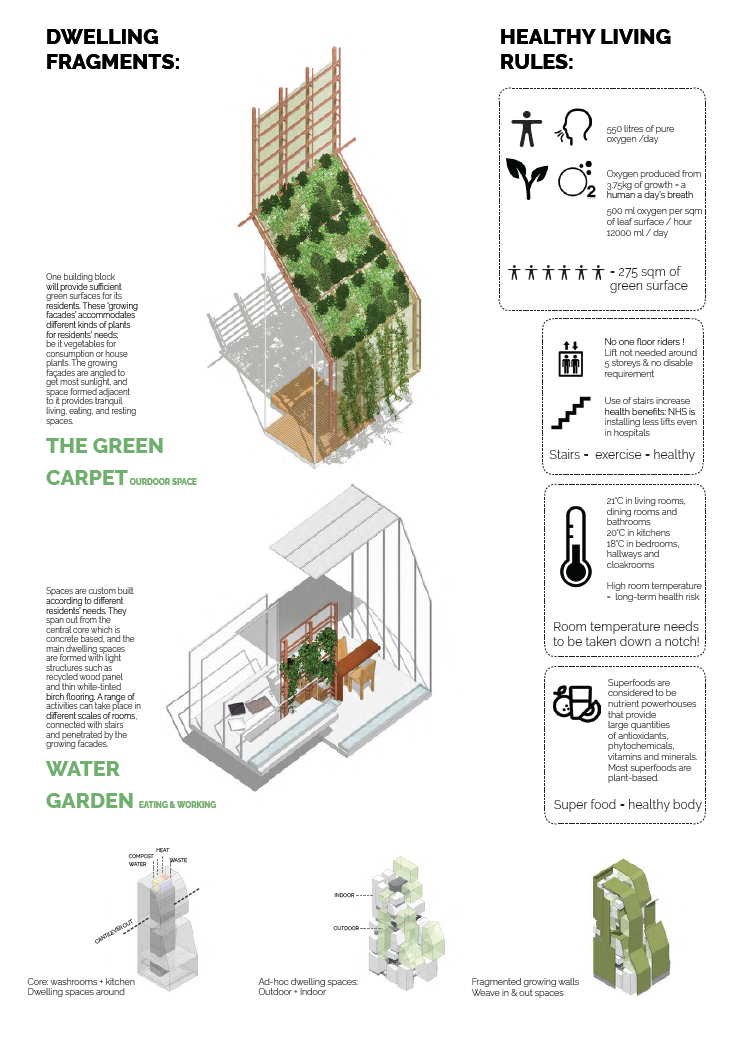

Super Park Royal

Beebreeder Competition

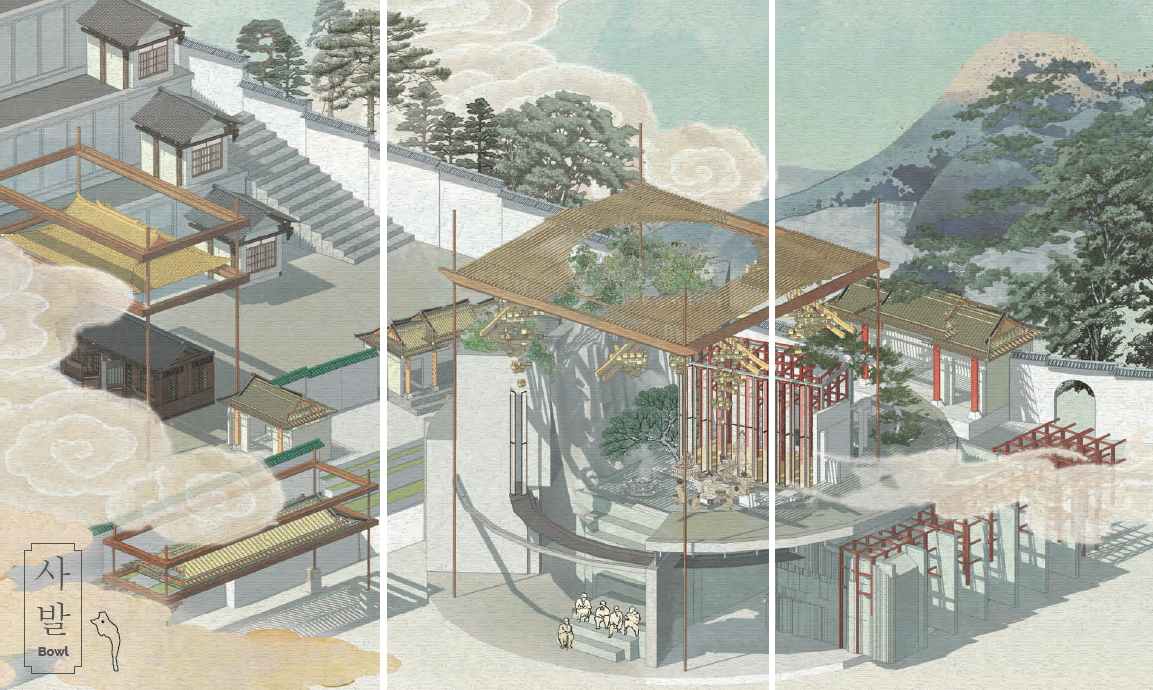

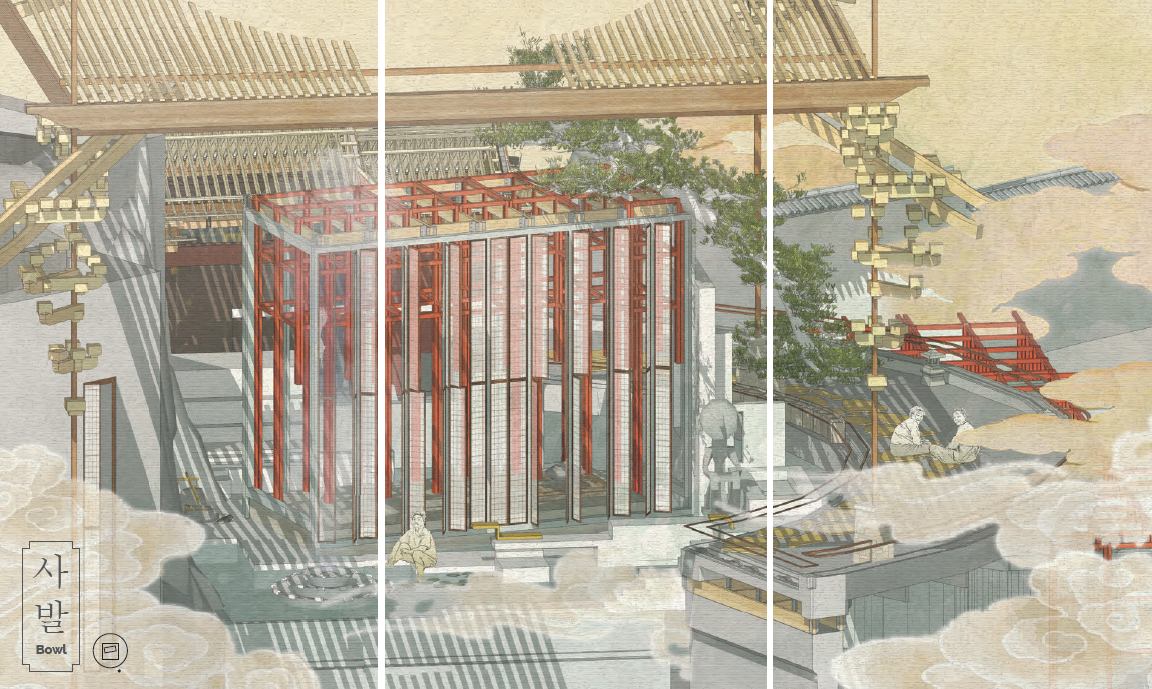

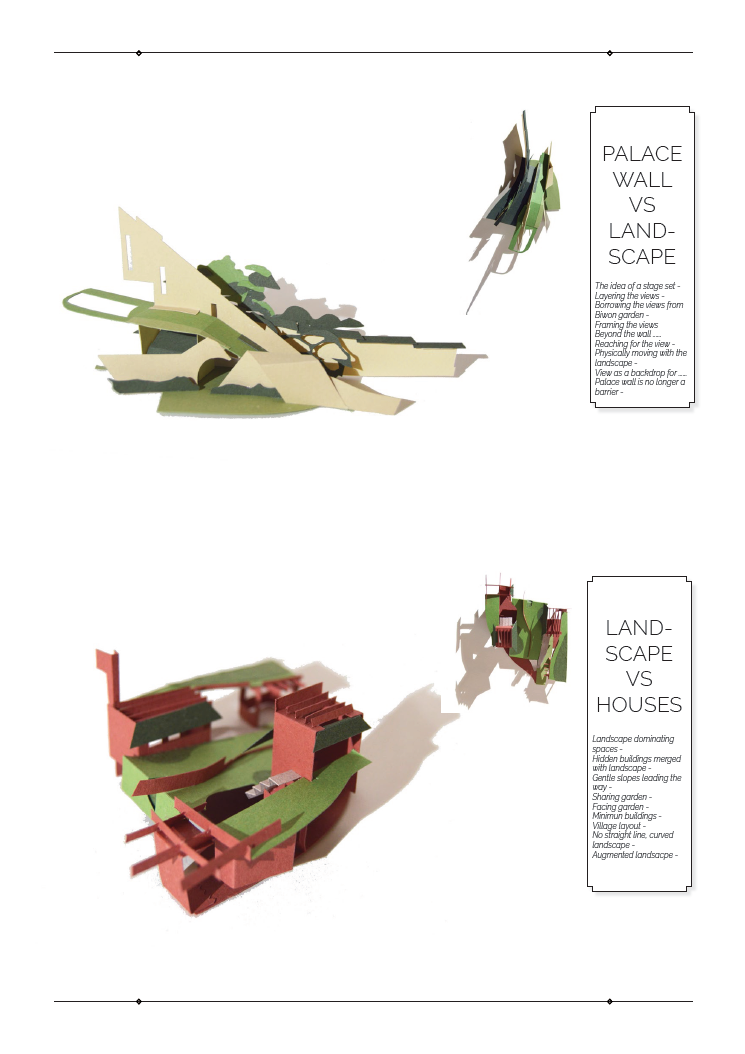

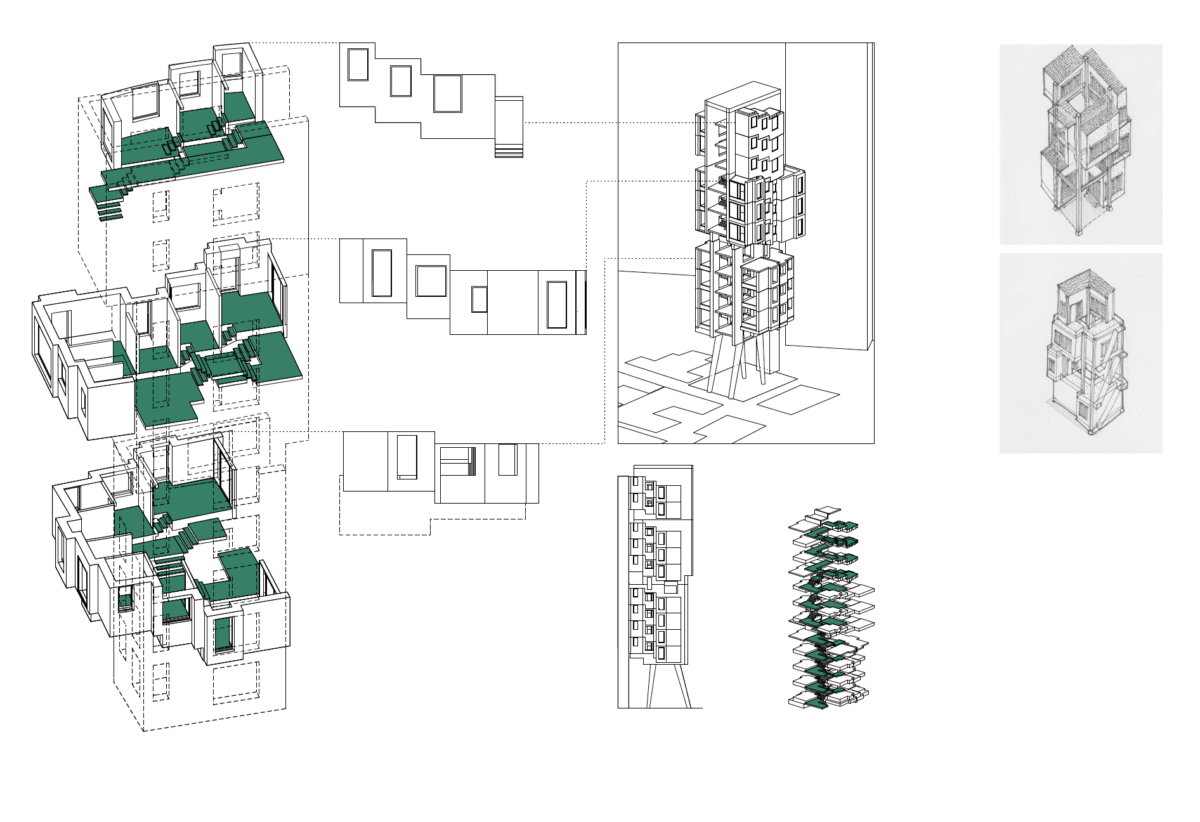

(RE) Placing the Urban Hanok

This project sets out to question the position of historic housing stock within cities which have rapidly developed since its original construction. It highlights a current global phenomenon that residential areas of historic value, which are often located in premium locations in developed cities, have become expensive, tourist-orientated neighbourhoods. Focusing on Seoul’s historic urban courtyard typology and the context in which it emerged in the 1930s, as well as the current environment in which it exists, the project discusses how contextual change results in a changed relevance of historic housing.

Focusing on Seoul’s remaining urban hanok neighbourhoods, the project investigates preservation strategies that have resulted in the majority of the city’s historic housing stock being rebuilt. The project employs Eunpyeong Hanok Village as a case study to investigate the Seoul Metropolitan Governments method of constructing entirely new urban hanok villages as a way of preserving the housing typology.

The project attempts to re-evaluate recognised approaches for urban development and preservation. It highlights a current tendency of urban preservation strategies resulting in the creation of exclusive and expensive contemporary neighbourhoods. It raises a question at a global scale of whether there is an alternative approach, where historic housing can be adapted in order to benefit local communities, and used as a site for additional affordable housing.

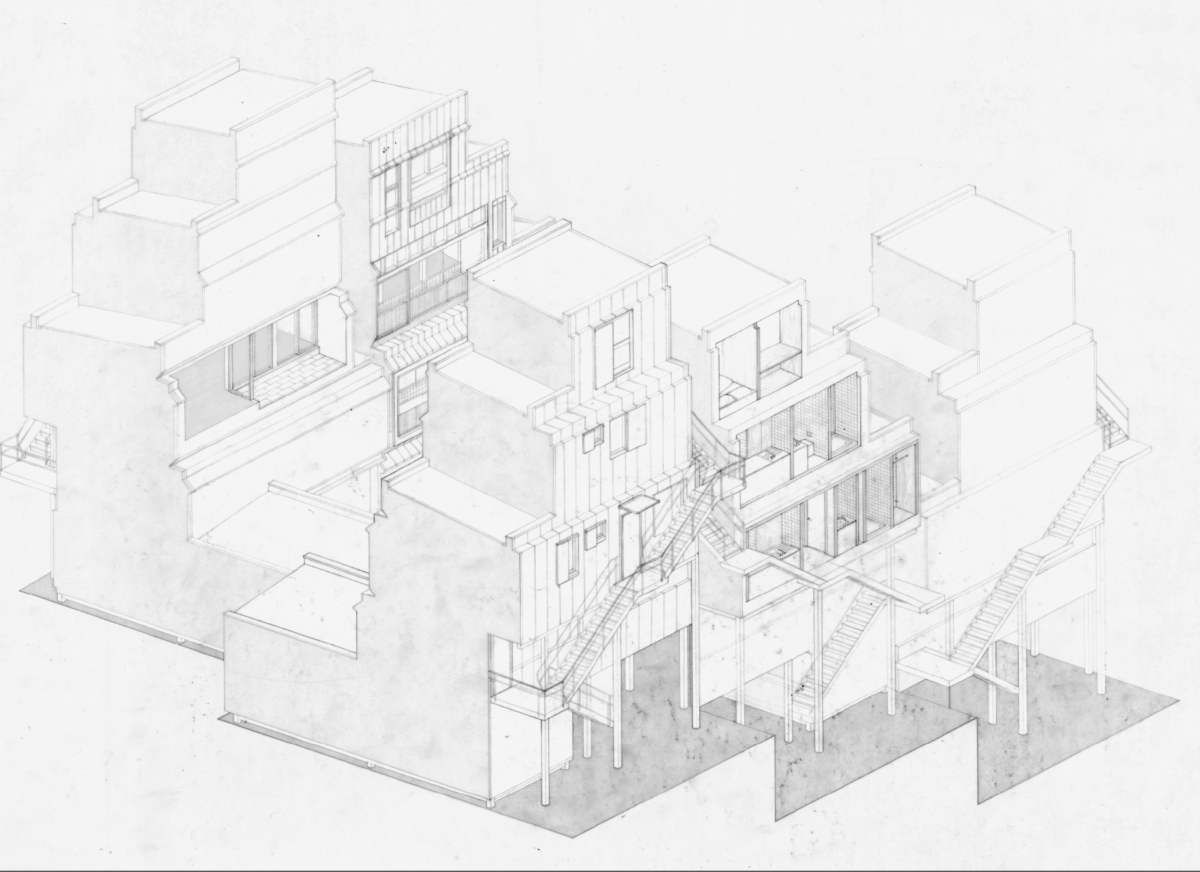

The project rejects theories on preservation which emphasise material originality and replicating aesthetic appearance. Instead, it focuses on the importance of preserving the social qualities and ideas on domestic space embedded within housing. It identifies the city as a fluid system which is continually and incrementally changing. Historic housing stock should therefore be allowed to adapt and change to different contexts and new generations of inhabitants.

As shown in Seoul, rapid urban development can force a city to re-evaluate its historic housing stock. Surrounded by newer, taller and modernised developments, historic housing stock can appear outdated.

If historic housing stock is not reinvented within new contexts, it risks becoming irrelevant. It may be demolished and replaced with something new – as with the urban hanoks over the past 50 years – or preserved and converted into an exclusive typology, beneficial for tourism or a privileged few.

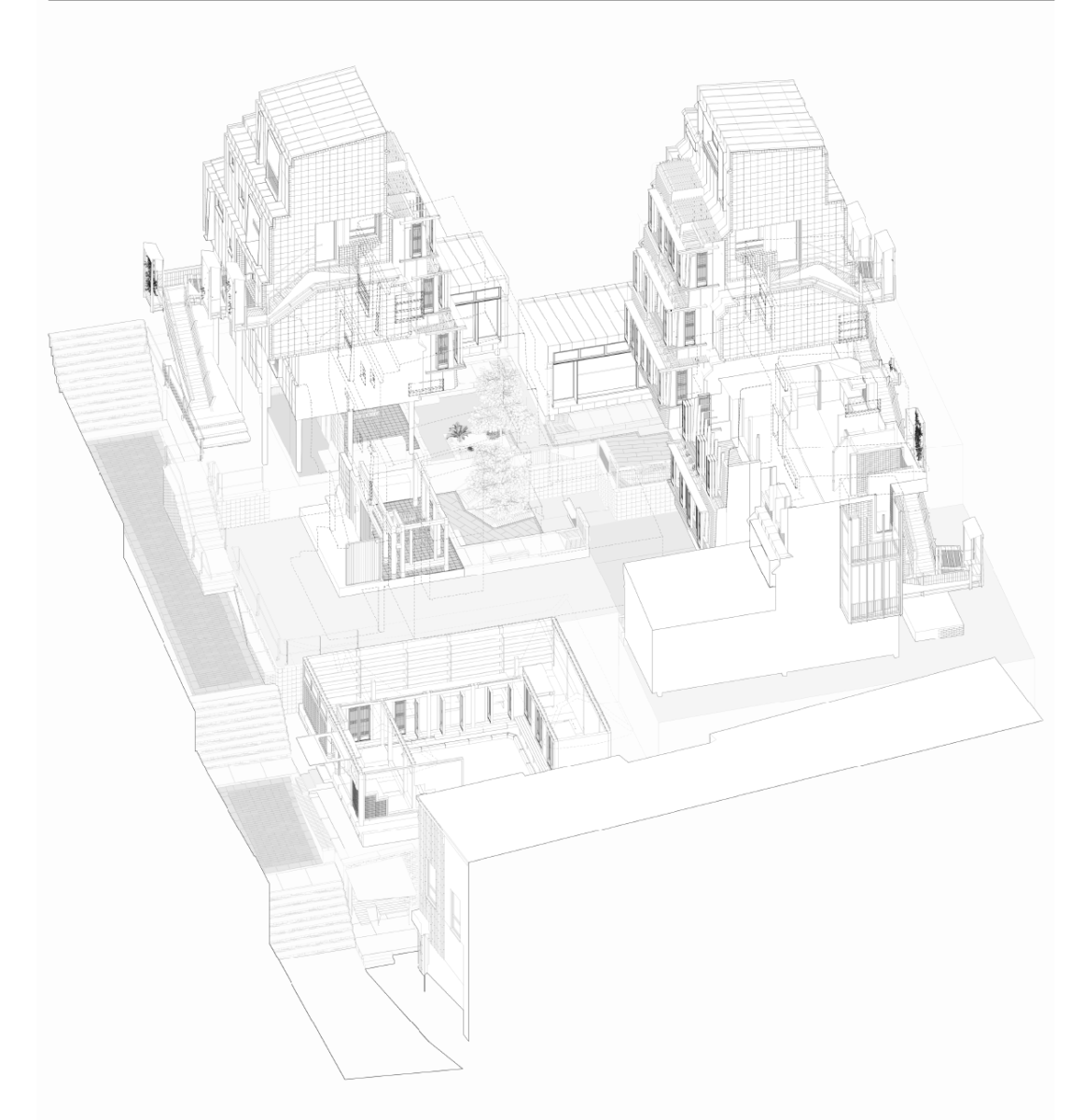

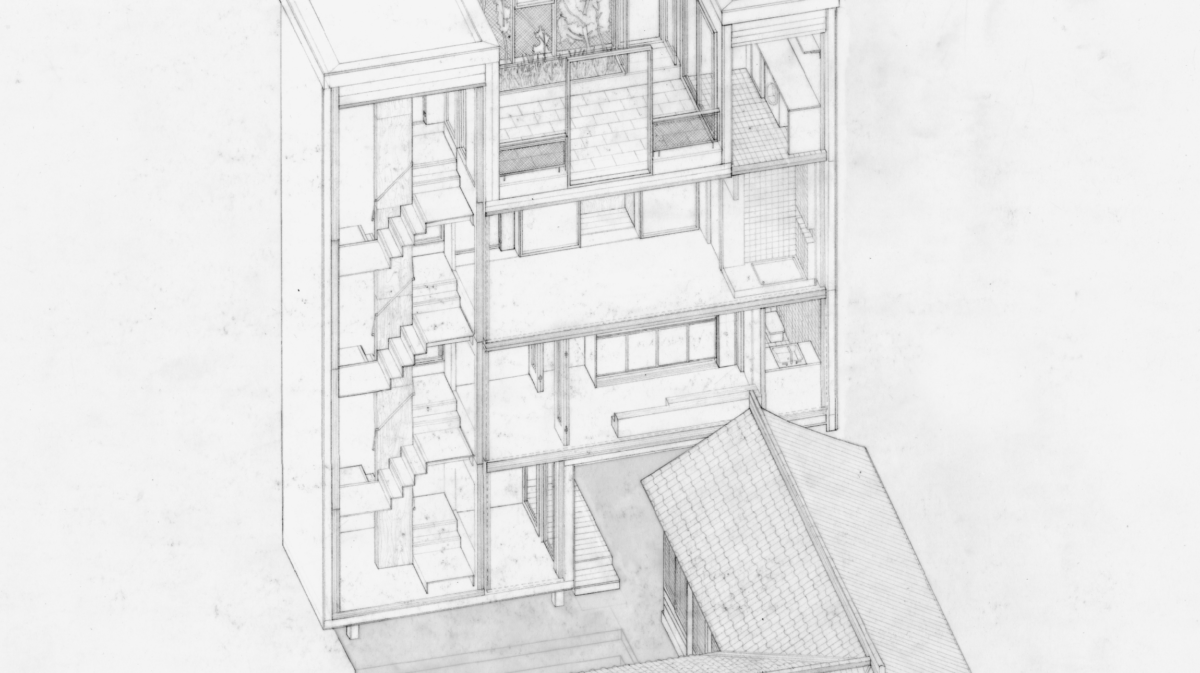

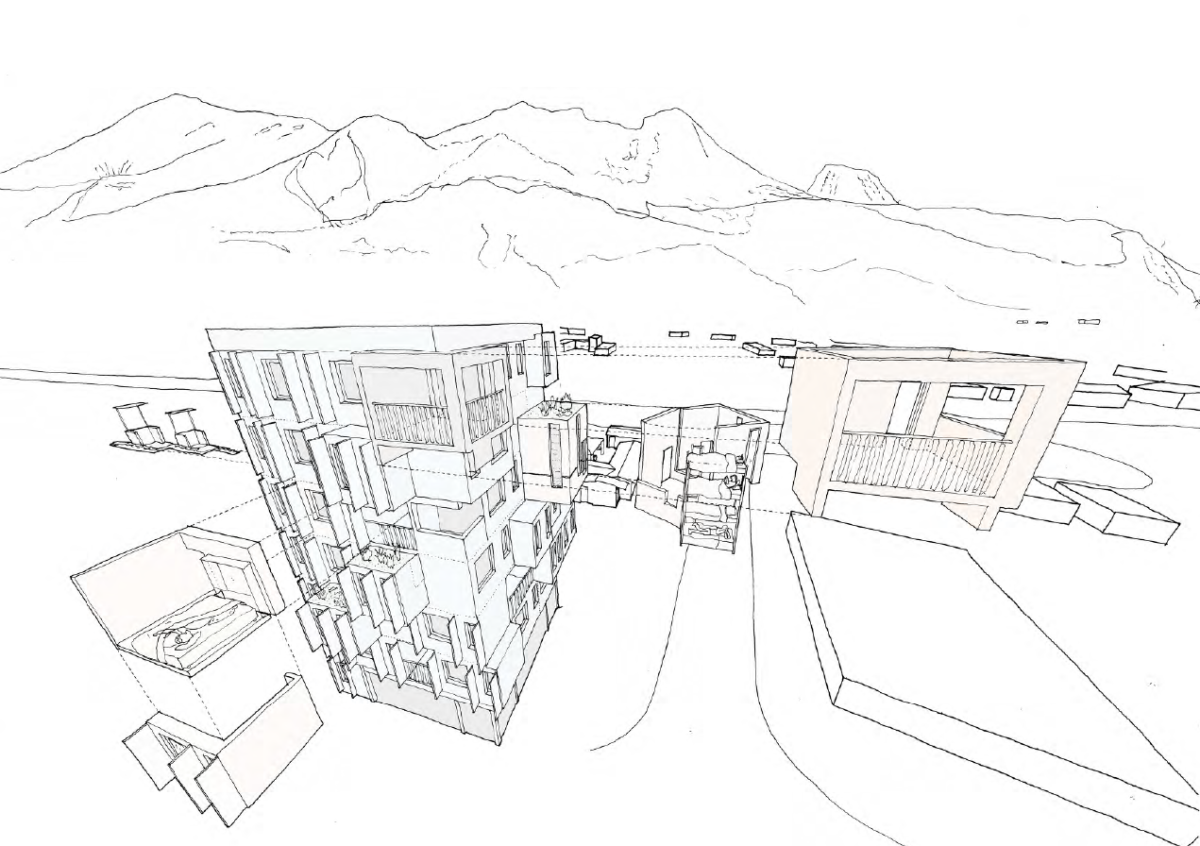

The project speculates on how housing design can be allowed to evolve. It does this by studying the existing condition of the urban hanok is terms of its structural and spatial design as well how it has been adapted and appropriated by residents. The design then provides a higher density typology which introduces contemporary construction methods and ideas on inhabitation, while retaining a layout influenced by the original urban hanok form.

The design provides an example of a reinvented typology that responds to the contextual needs of the present day. It also demonstrates how housing can be additively changed on a plot-by-plot basis. It opposes both a broad master-planned re-development of an area, or preserving a neighbourhood as a whole.

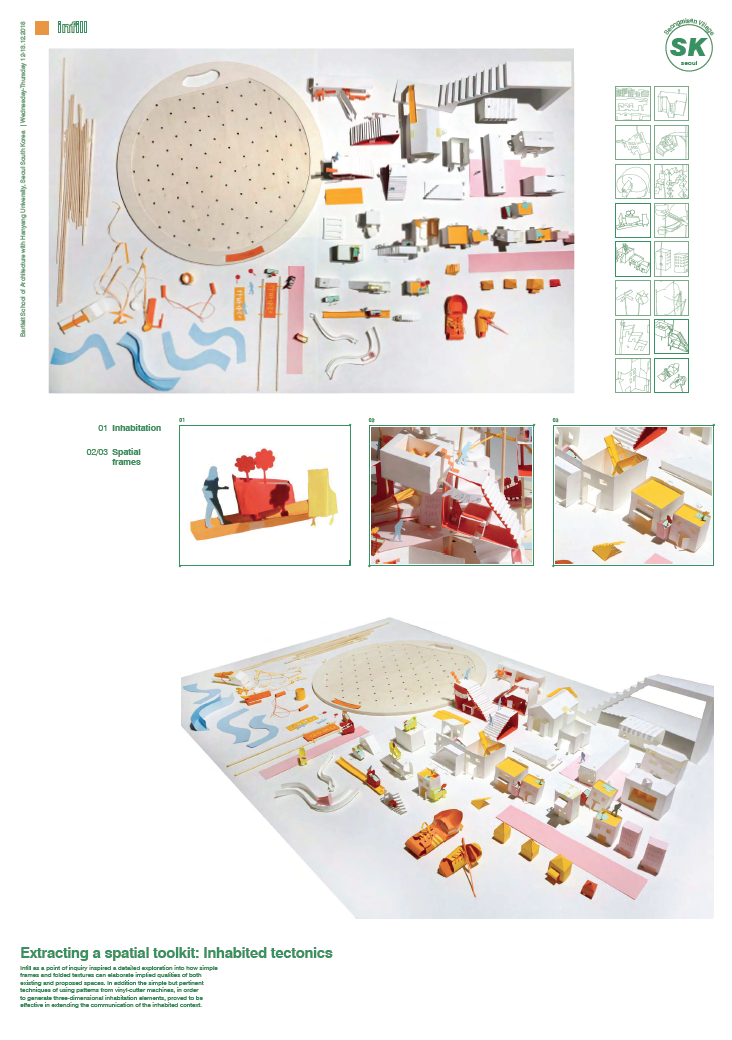

Spatial Infringement Agency, Seoul

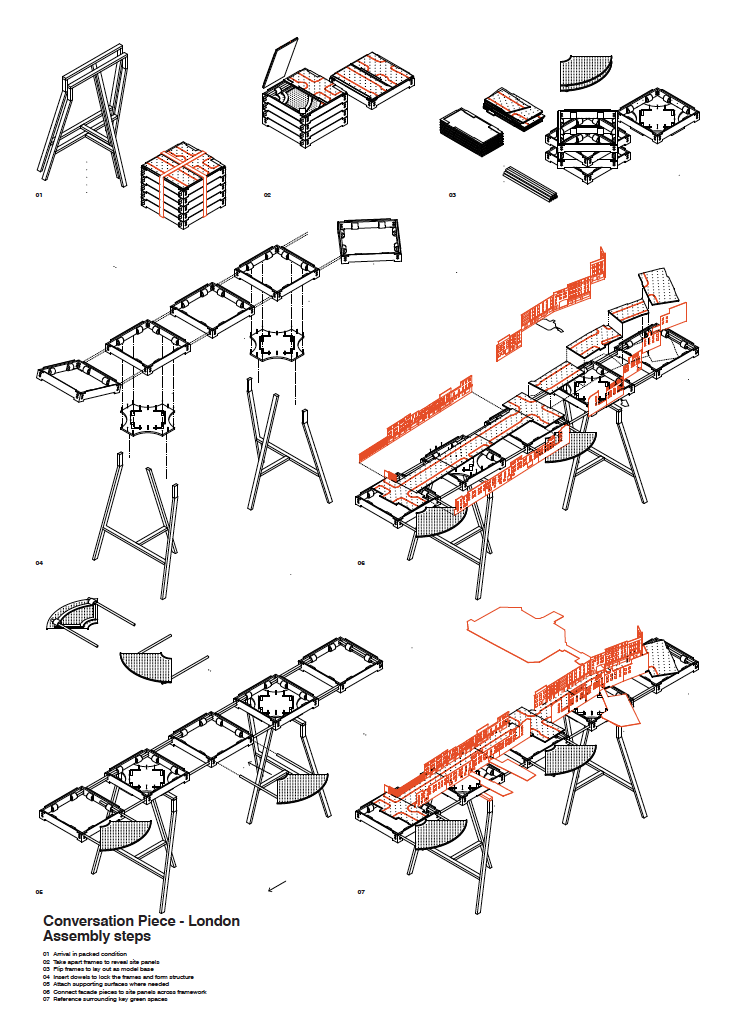

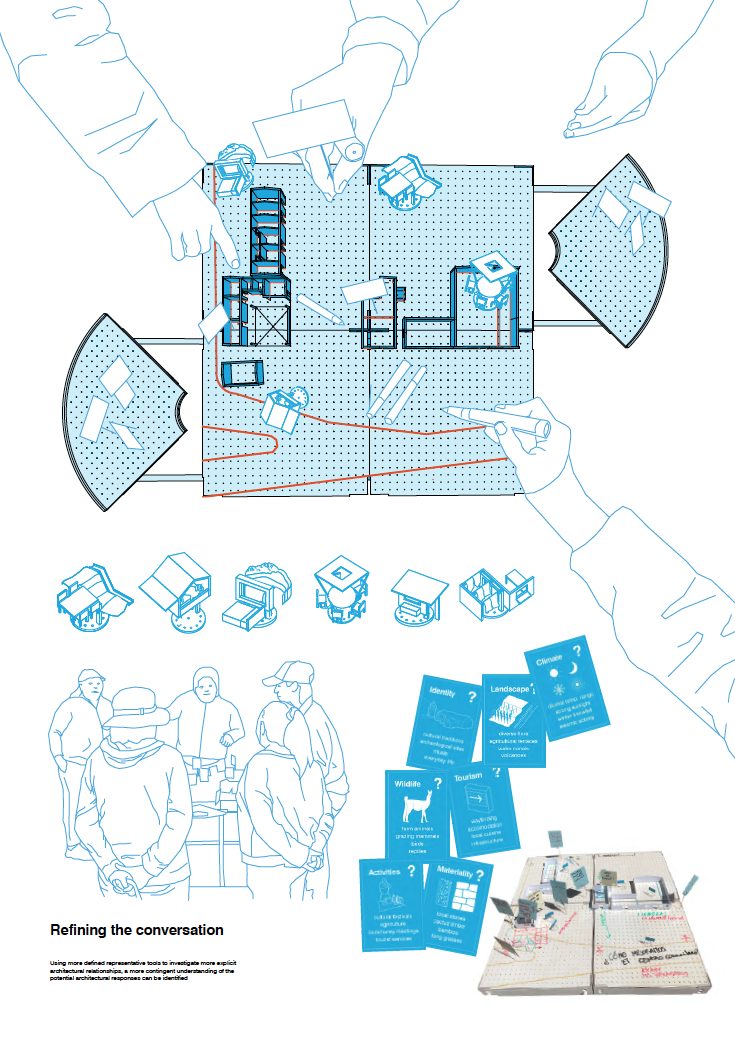

Toolkits for Participation – London, Seoul, Chile

Sewoon Sanga Pig Farm, Seoul, South Korea

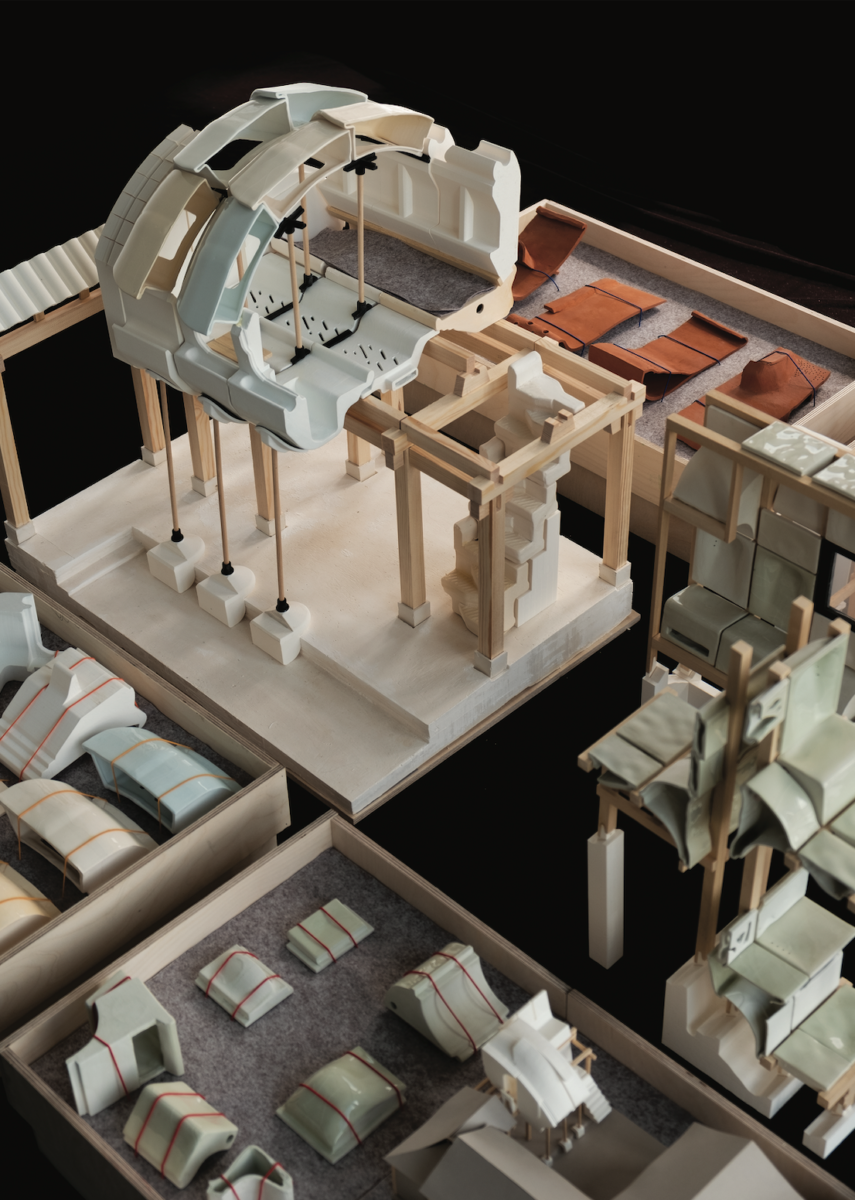

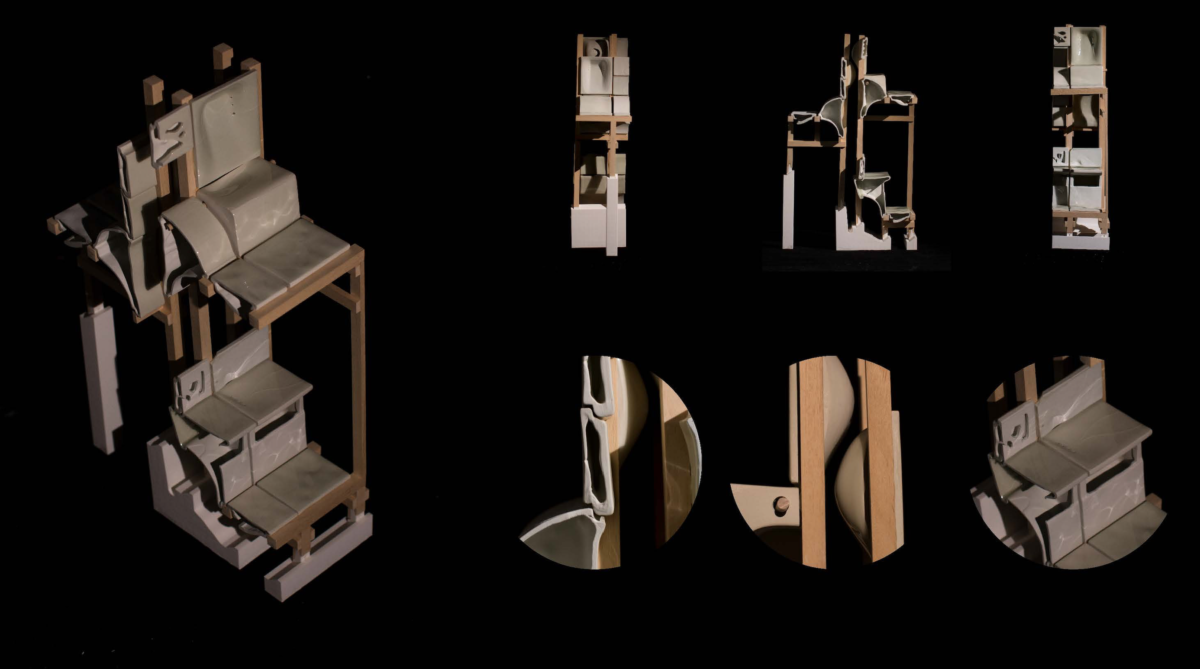

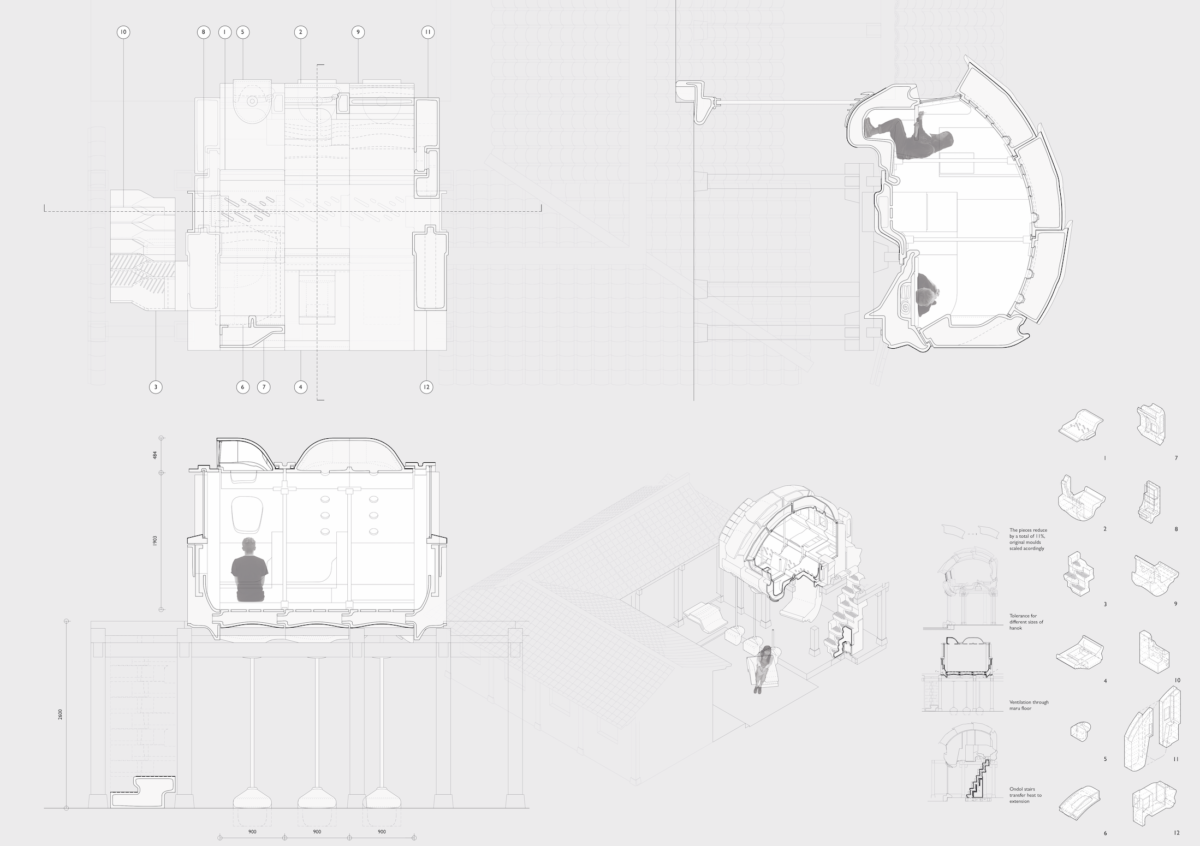

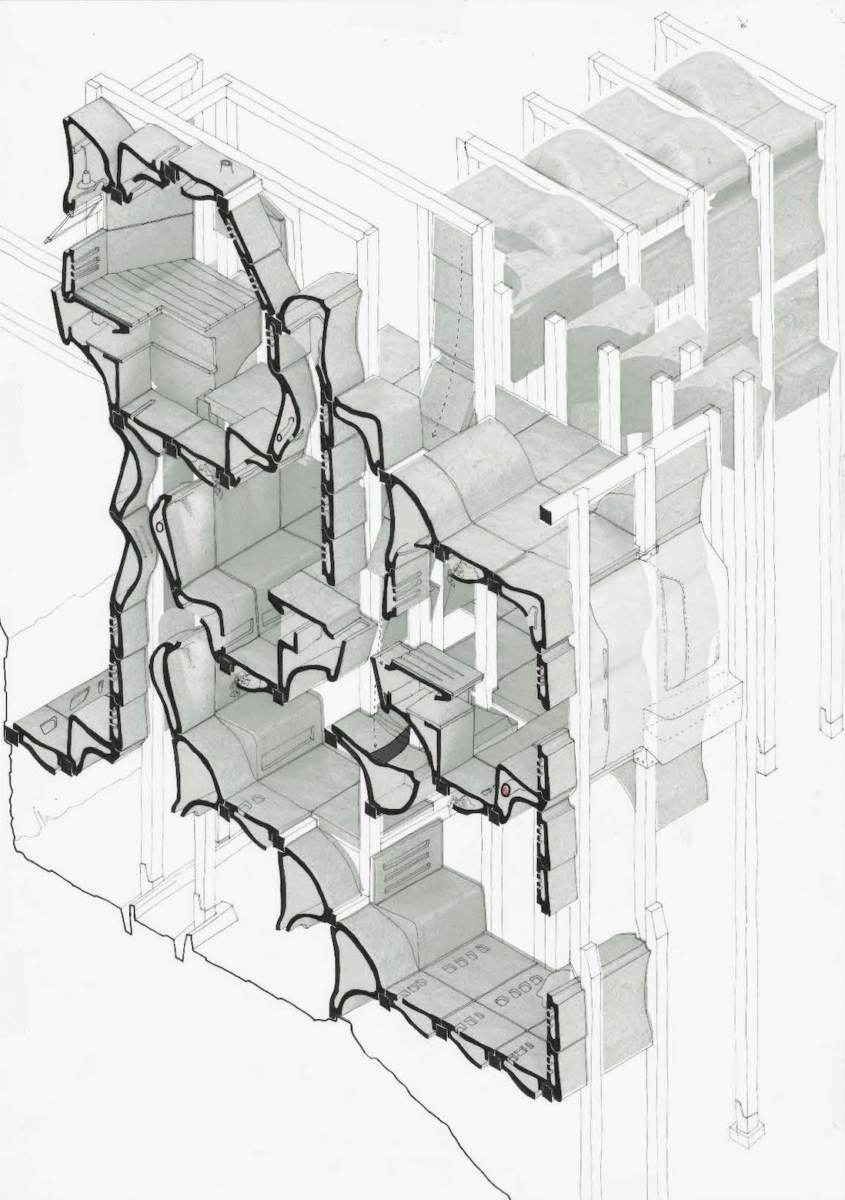

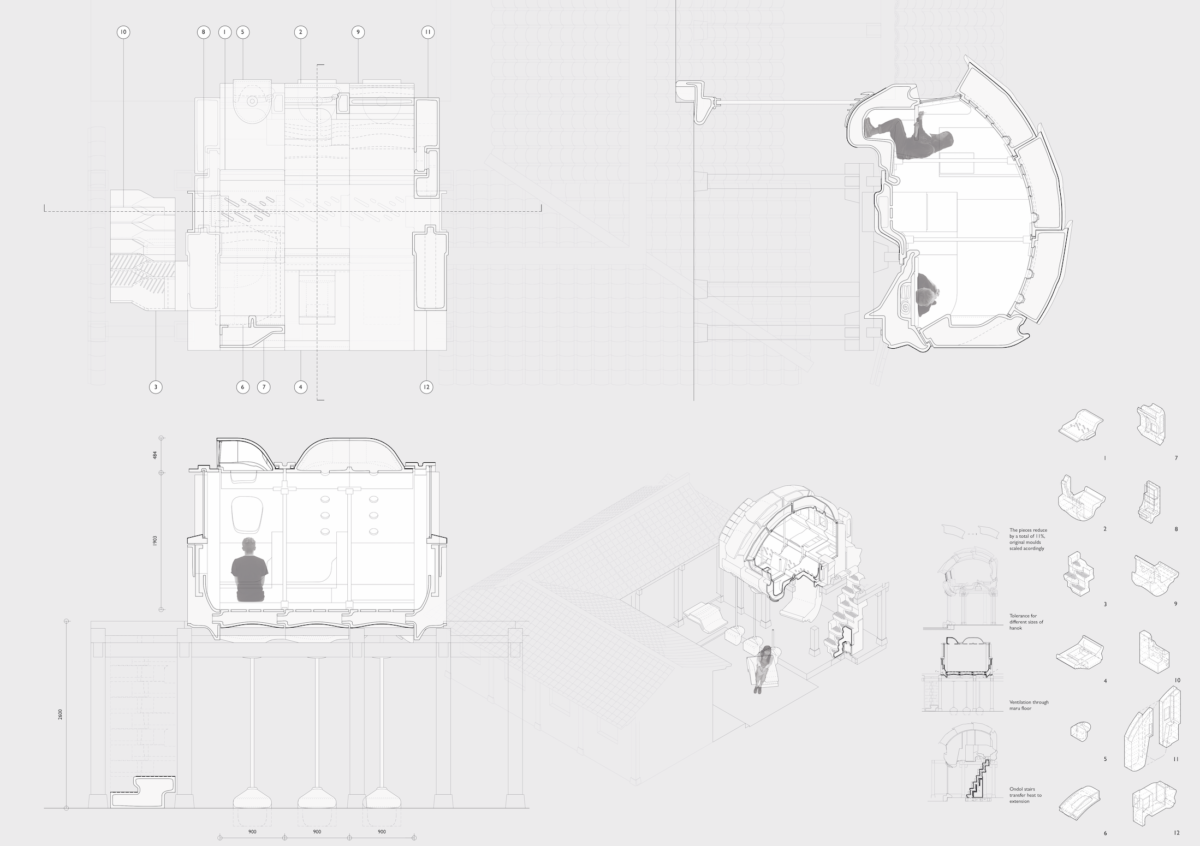

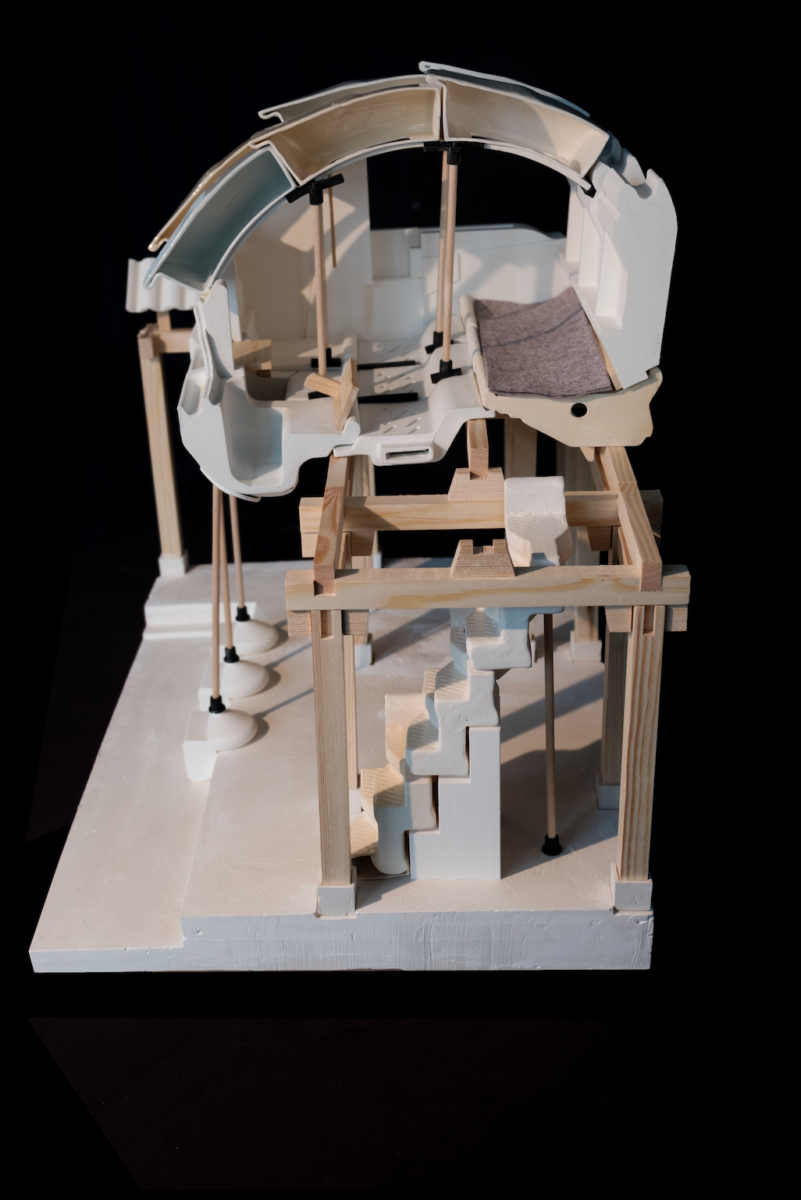

Ceramic House Seoul

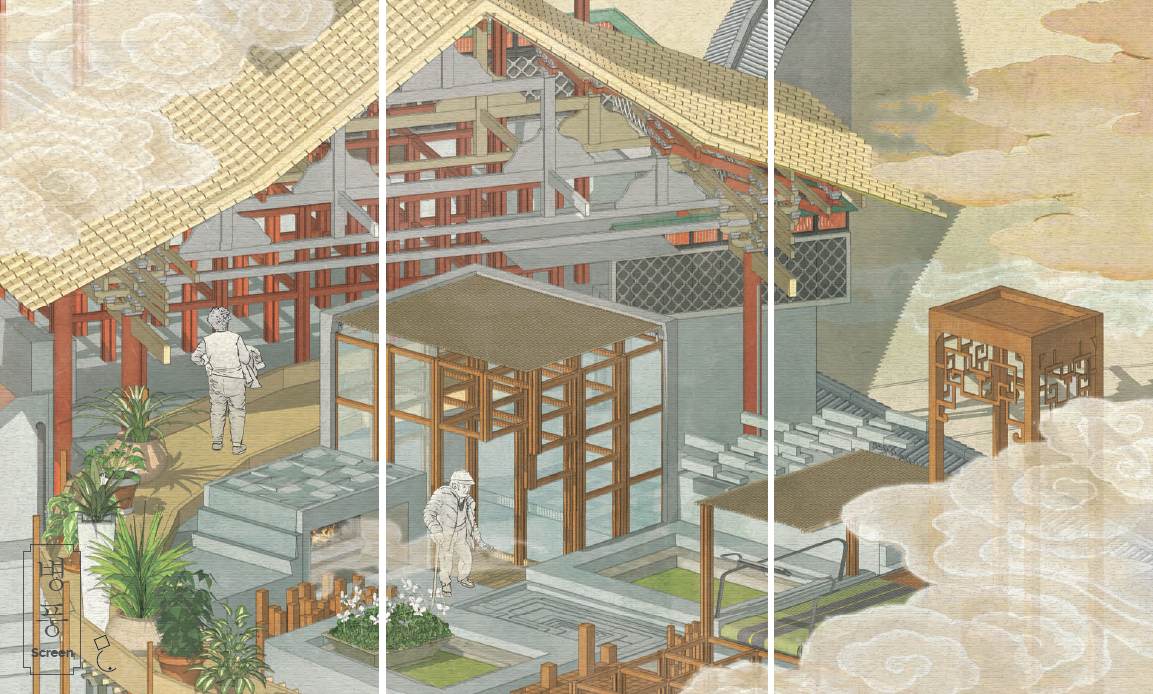

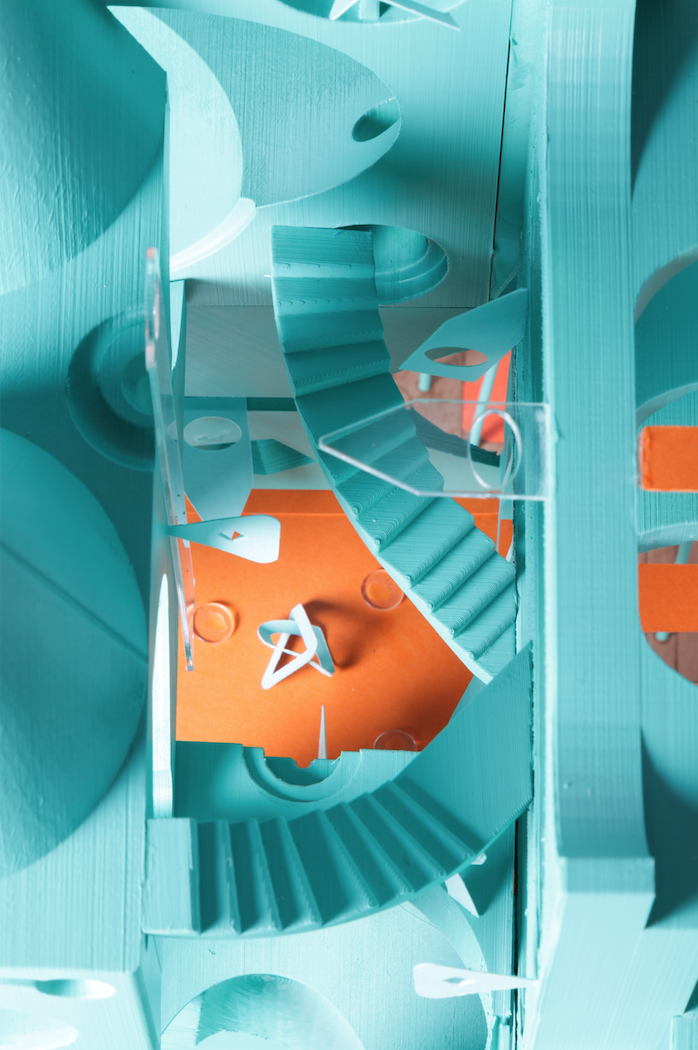

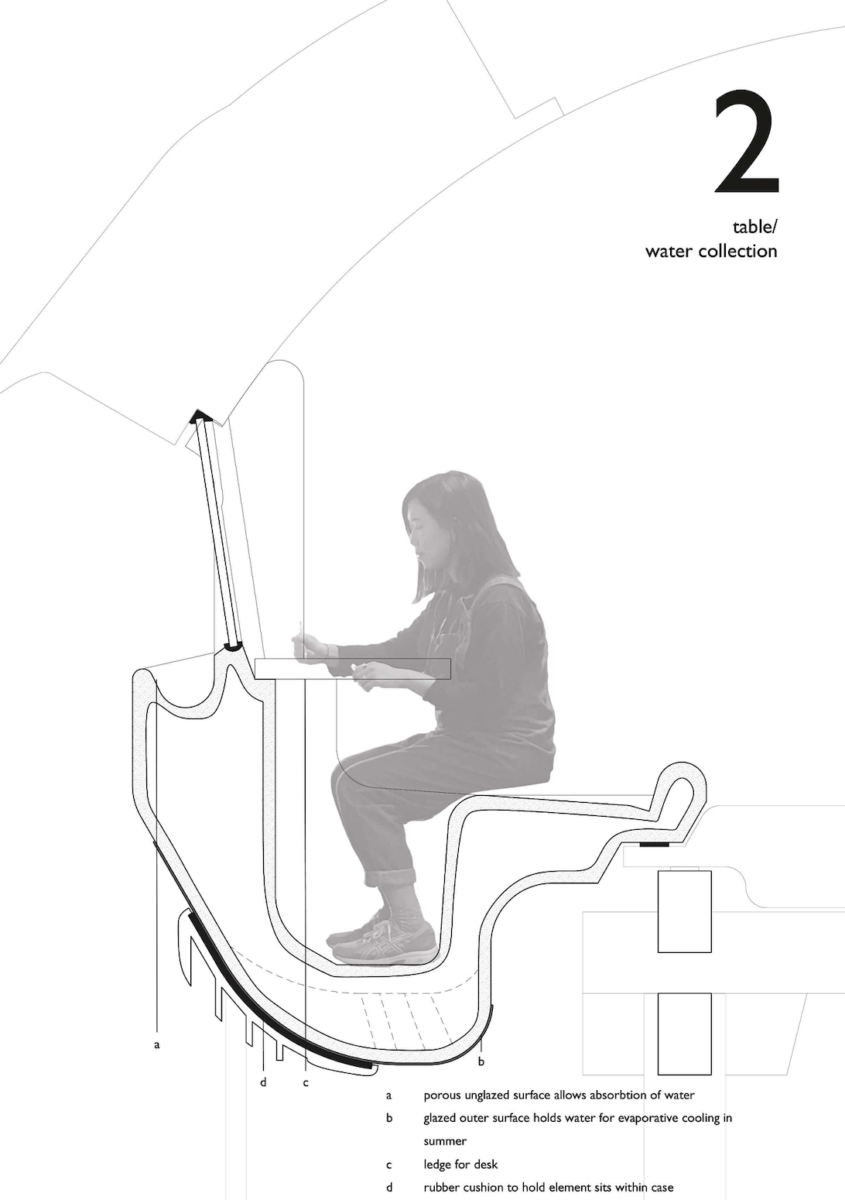

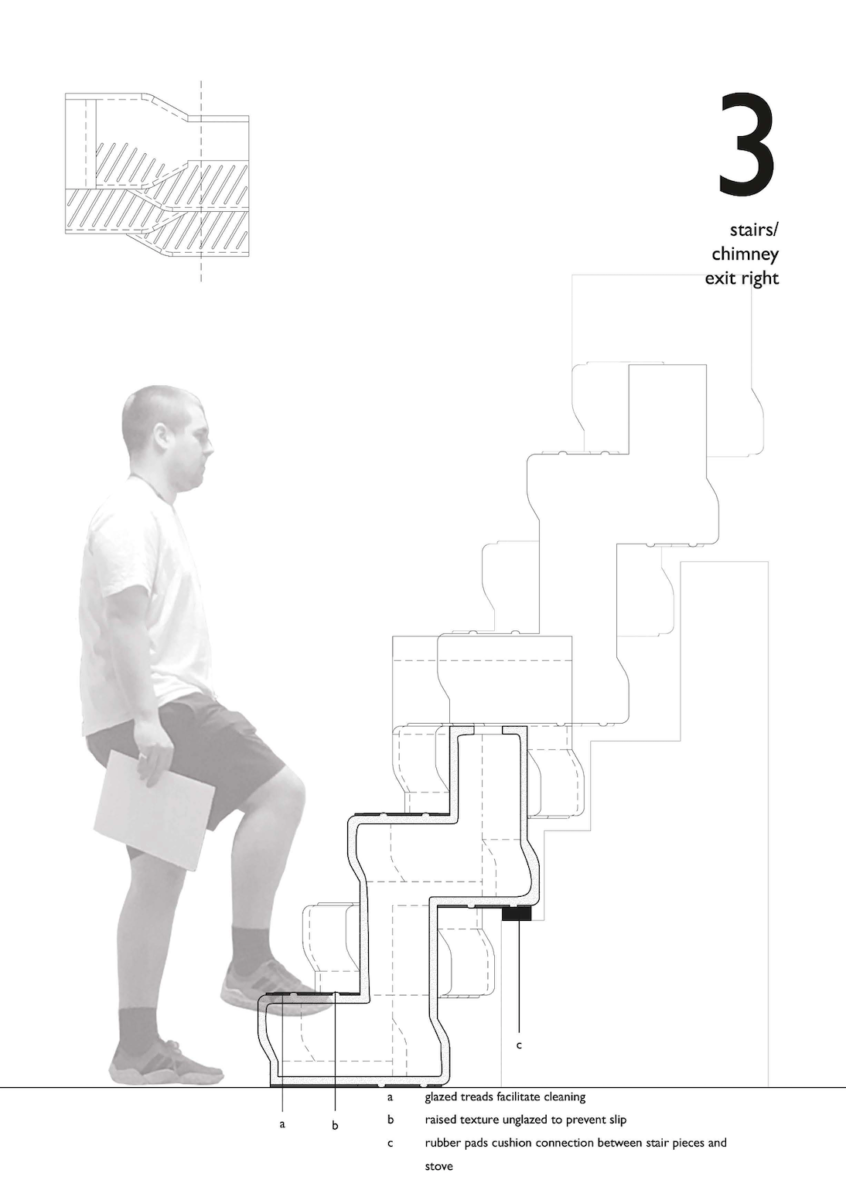

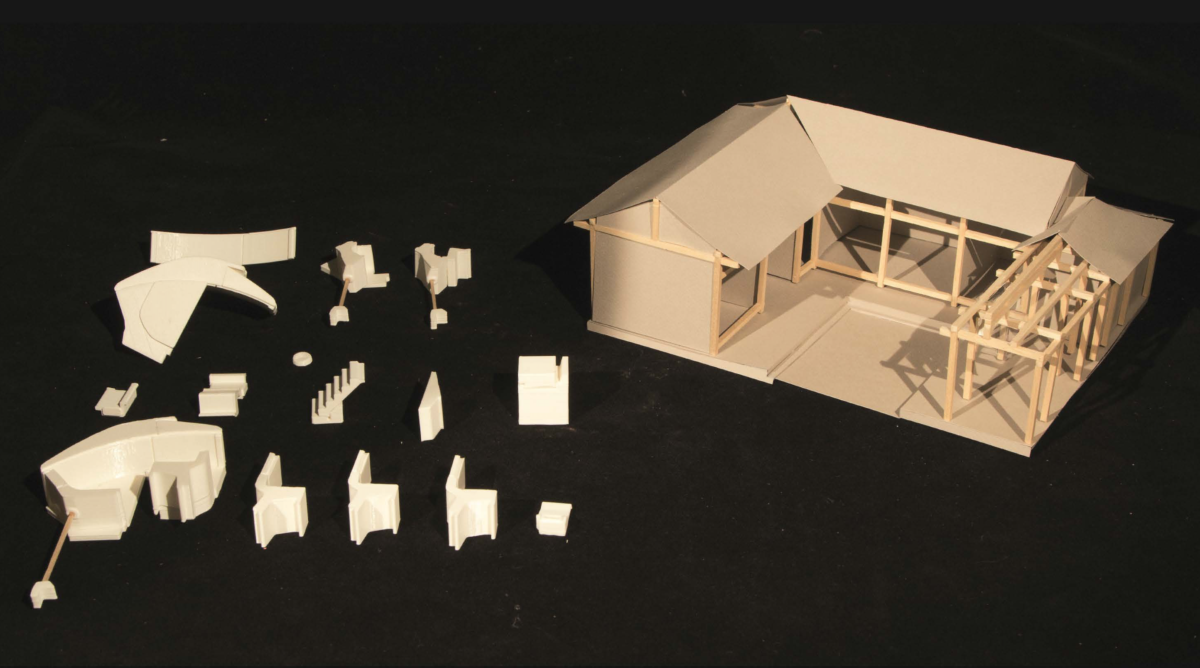

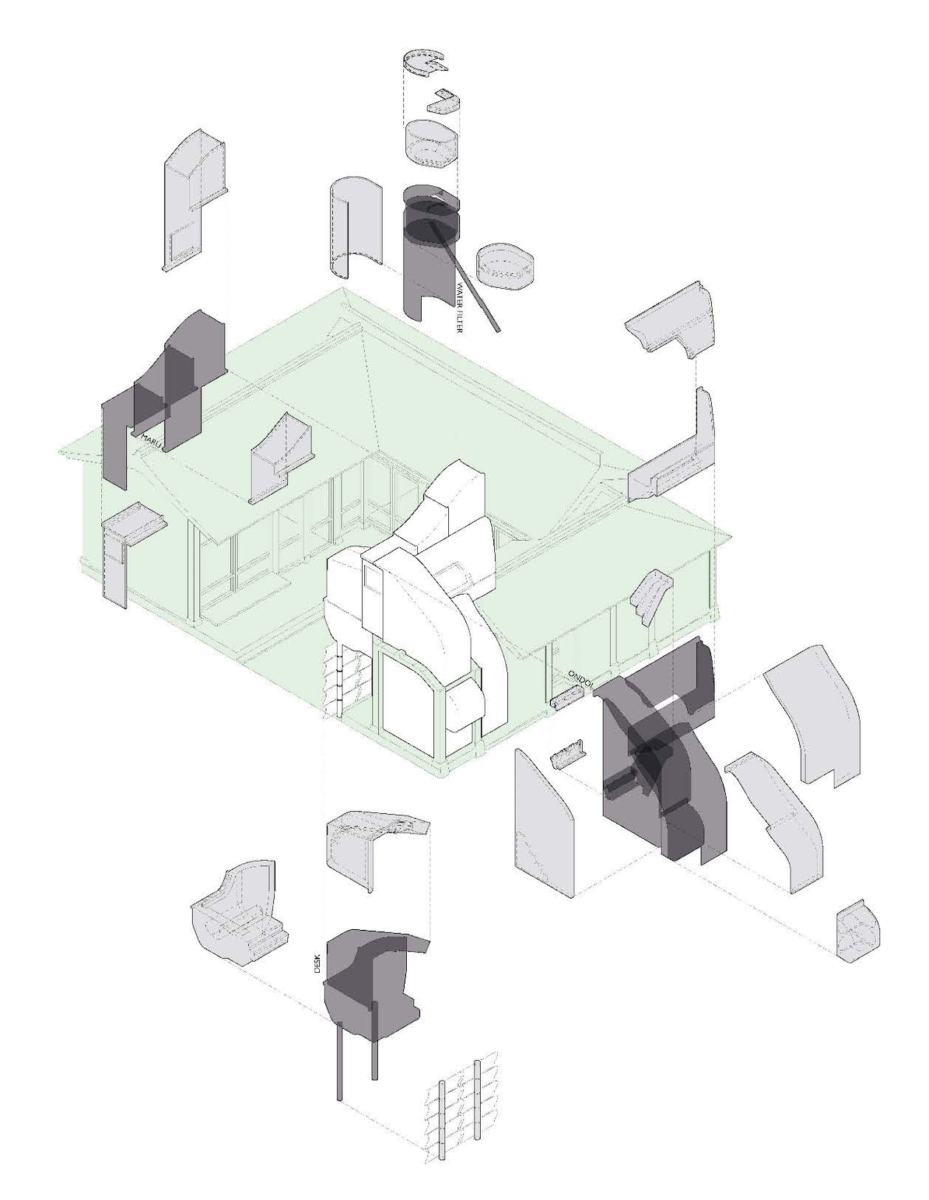

Korean ceramic craft was once prevalent in Seoul but is now found on the outskirts of the city. Buildings and crockery in Seoul are now predominantly steel, not clay. Taking inspiration from the urban courtyard typology of the Hanok; its ondol (heated) and maru (ventilated) floor, the project reintroduces environmental diversity into homes in Seoul.

The diverse Hanok floor encouraged a sedentary living condition, harnessing the thermal properties of the floor and using it as furniture. As the typology has been adapted over time some of this diverse environment has been lost. In response to the dual role of floor as furniture, slip cast ceramic extensions, built to lodge into the original timber frames of the Hanok will act as built-in furniture. In themselves they can also be used as individual furniture pieces elsewhere. The pieces are designed to contribute to the environmental diversity of the ceramic house and this influences the inhabitation within.

Each piece is formed in plaster moulds and fired in climbing kilns in Seoul as a recognition and experience of Korea’s ceramic tradition within the city. The build is slow and celebrates the application of craft within a community. Extensions can be built up over time in a suitable configuration for the existing home, with each piece ceramic furnishing.

The project examines ceramic craft at a furniture scale and how this might question existing inhabitation. The ceramic house proposes a crafted installation of environmental diversity to reintroduce a tradition which has been lost in the centre of Seoul.

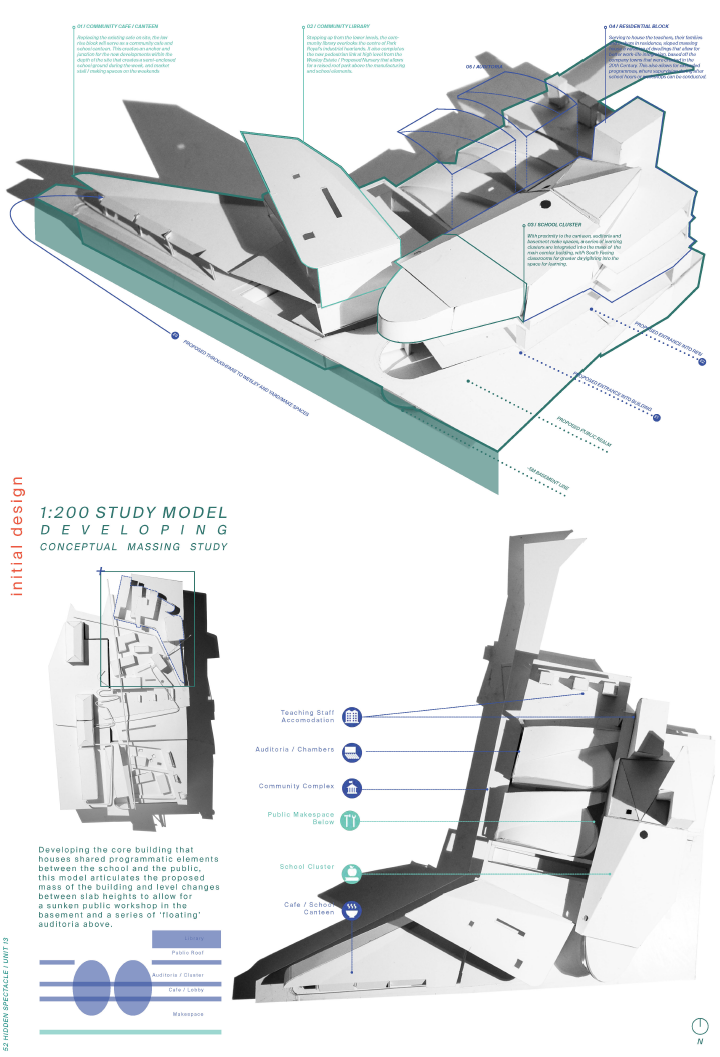

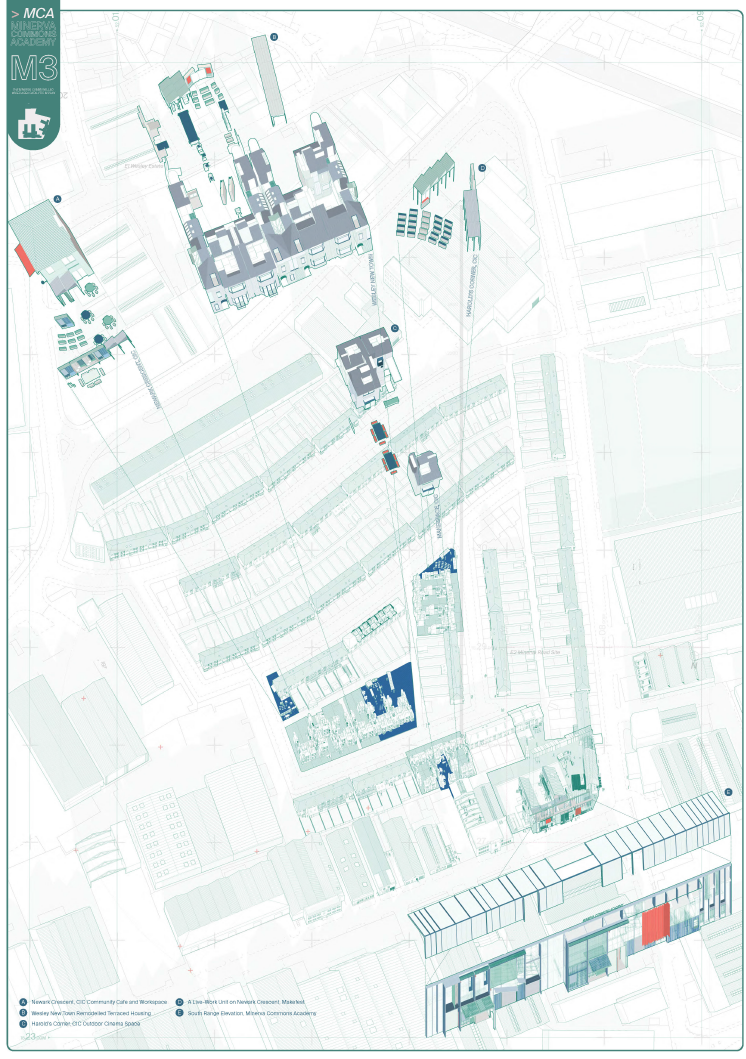

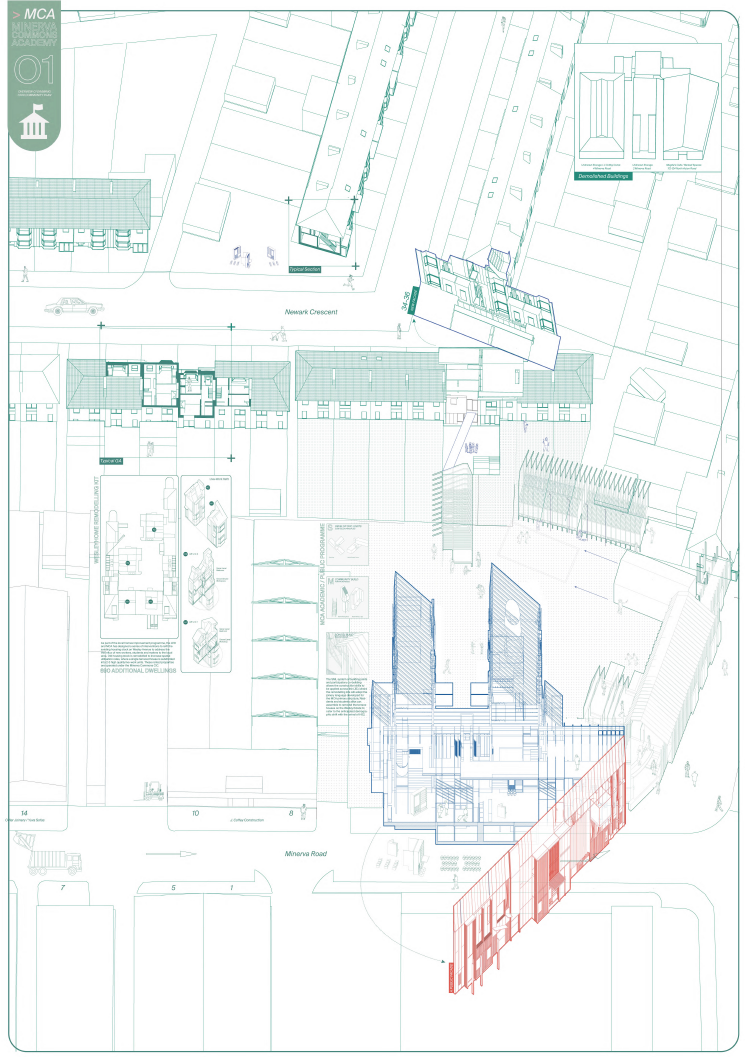

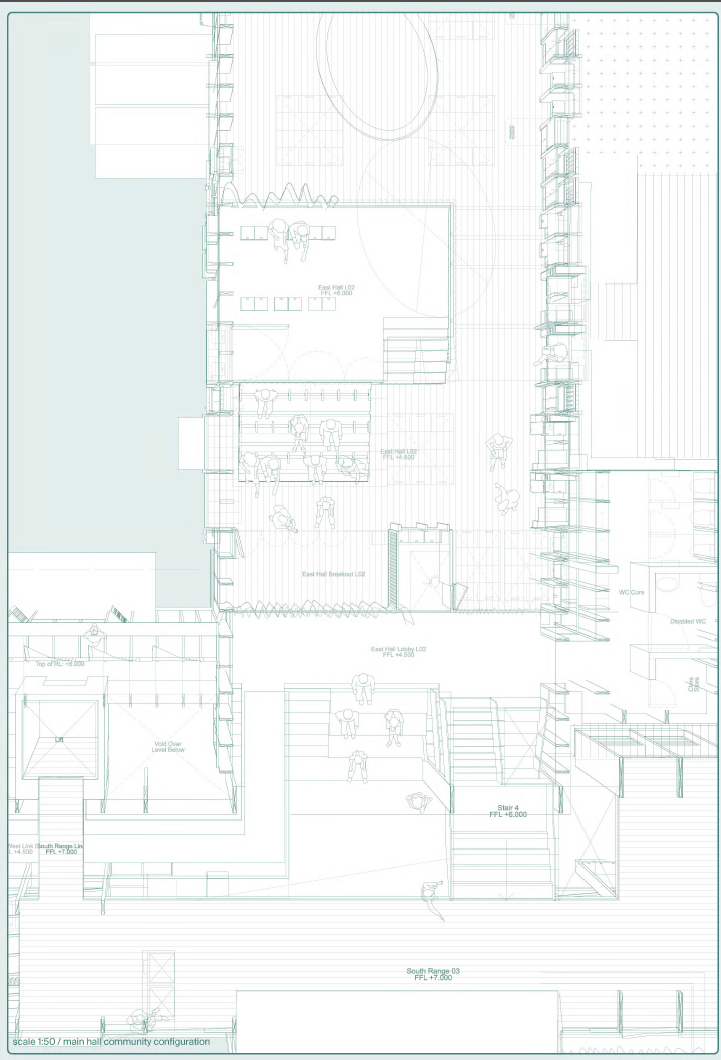

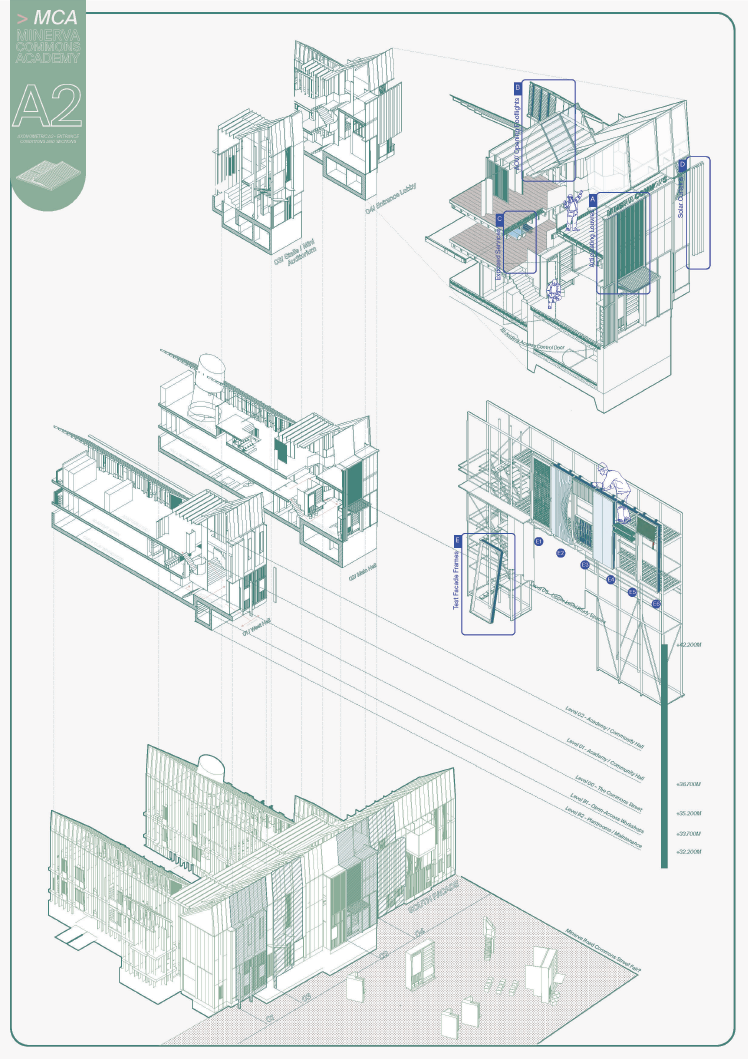

Wesley New Town School, Park Royal, London

A building as a teaching tool.

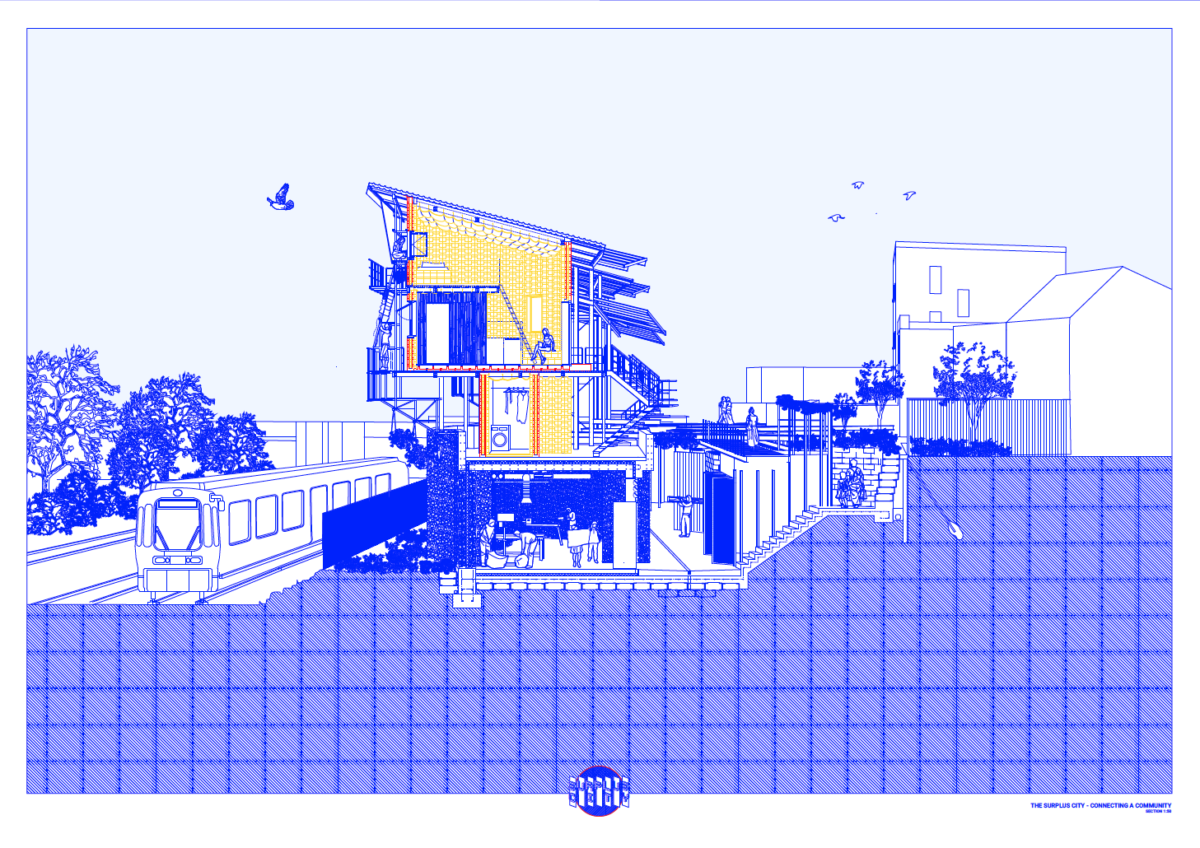

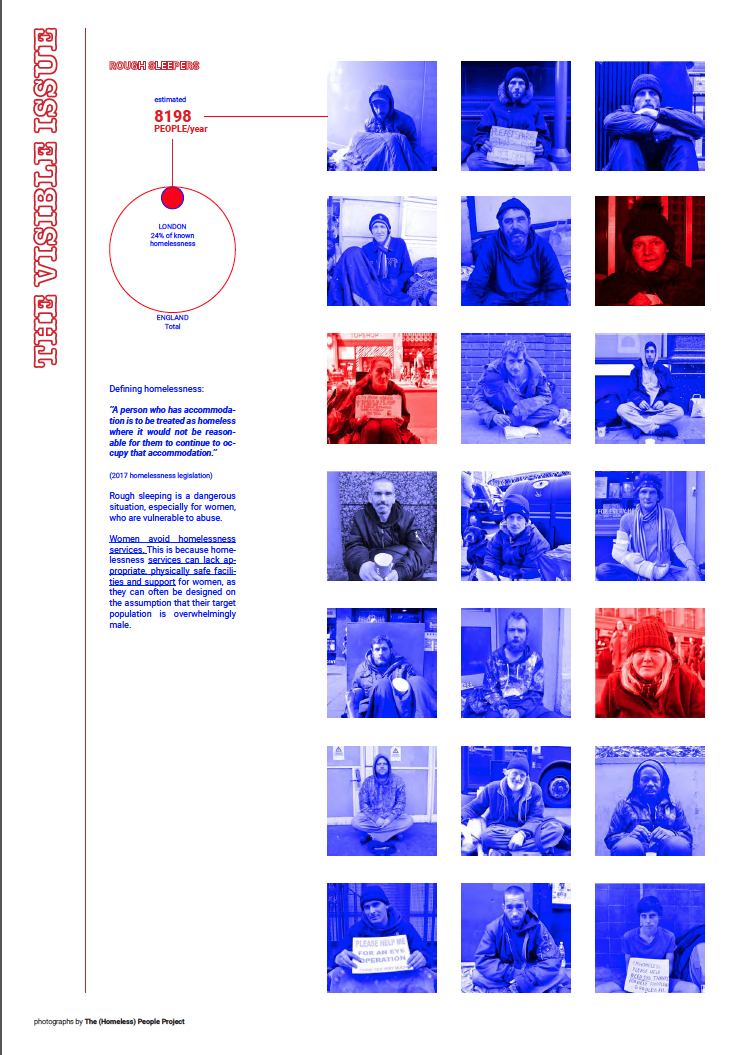

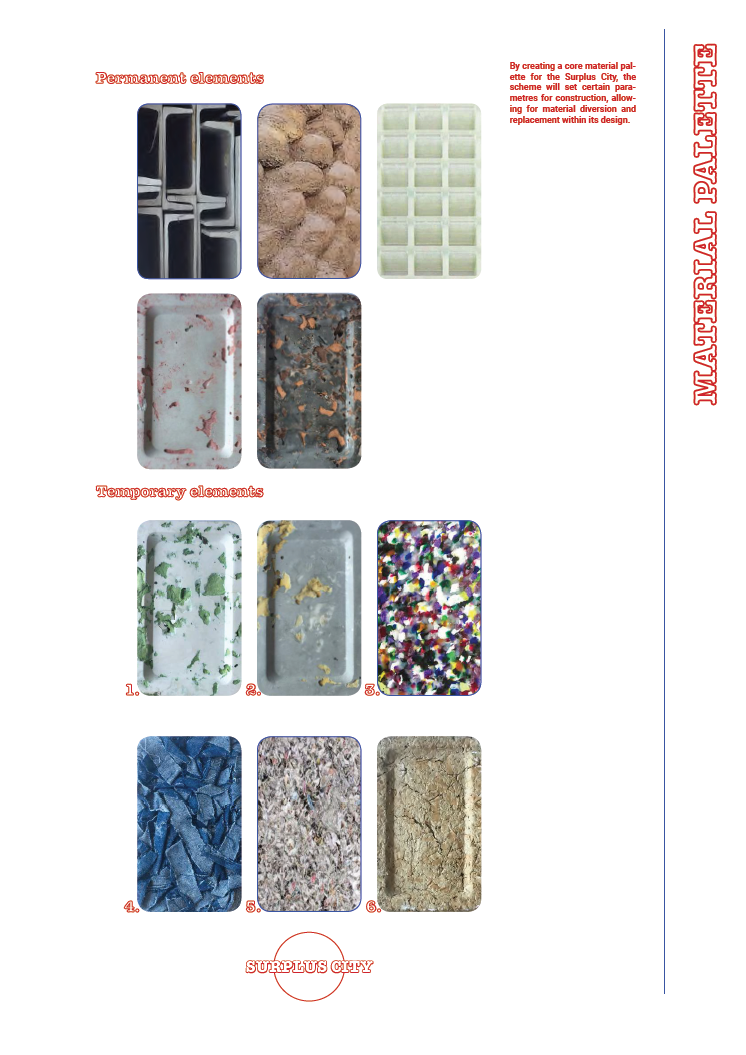

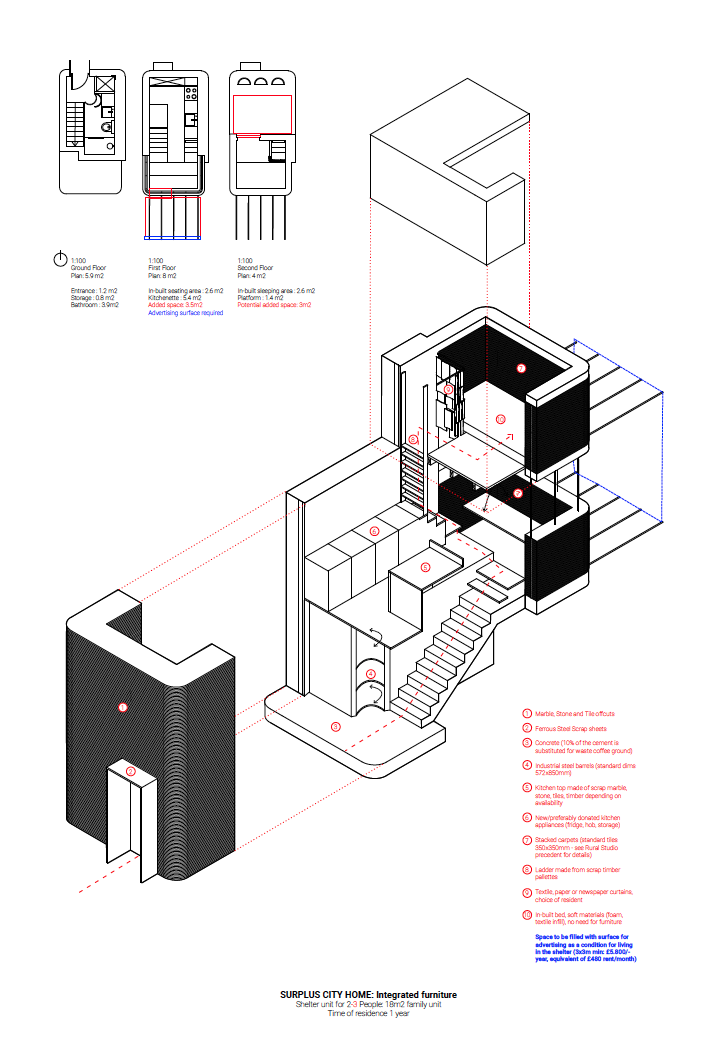

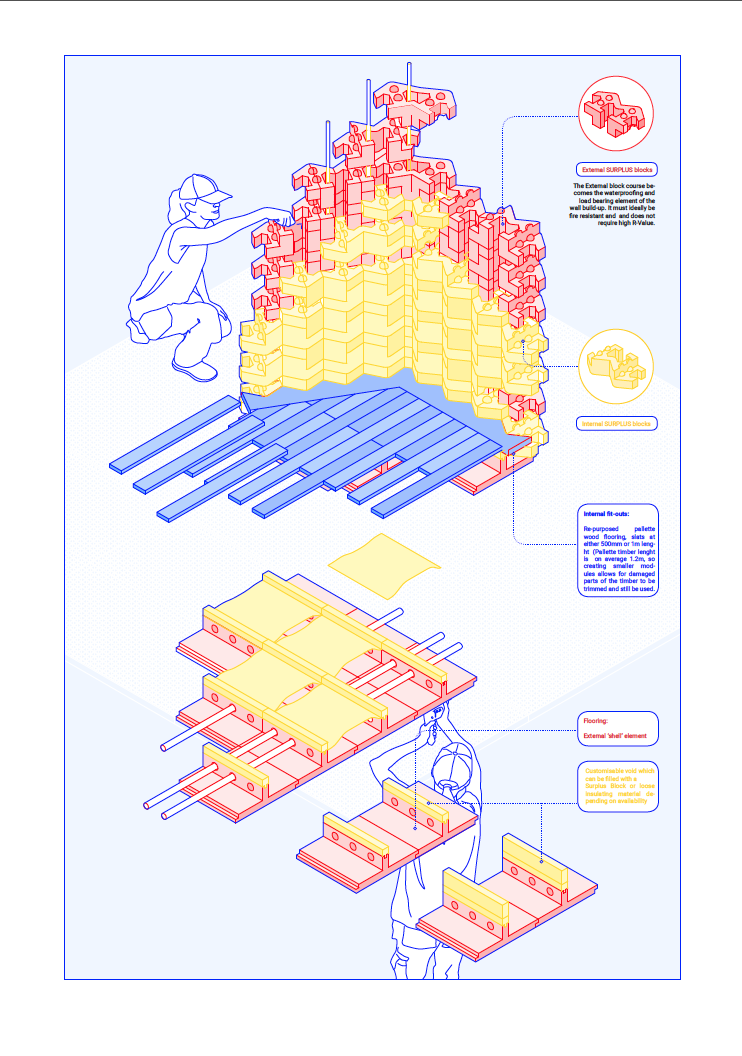

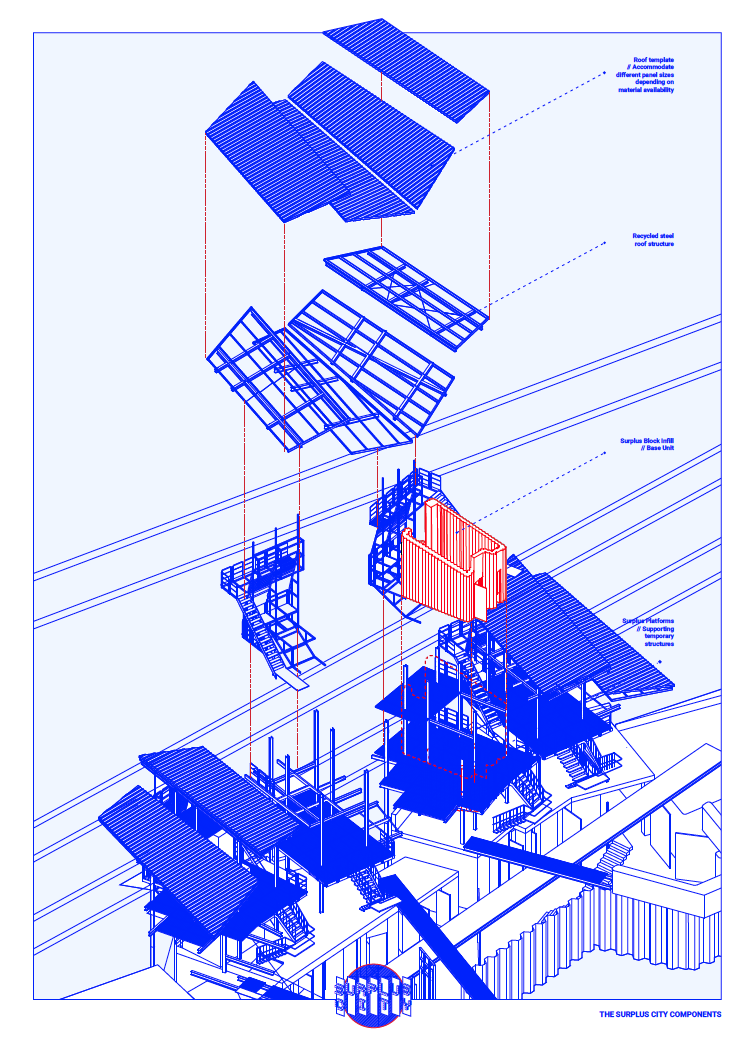

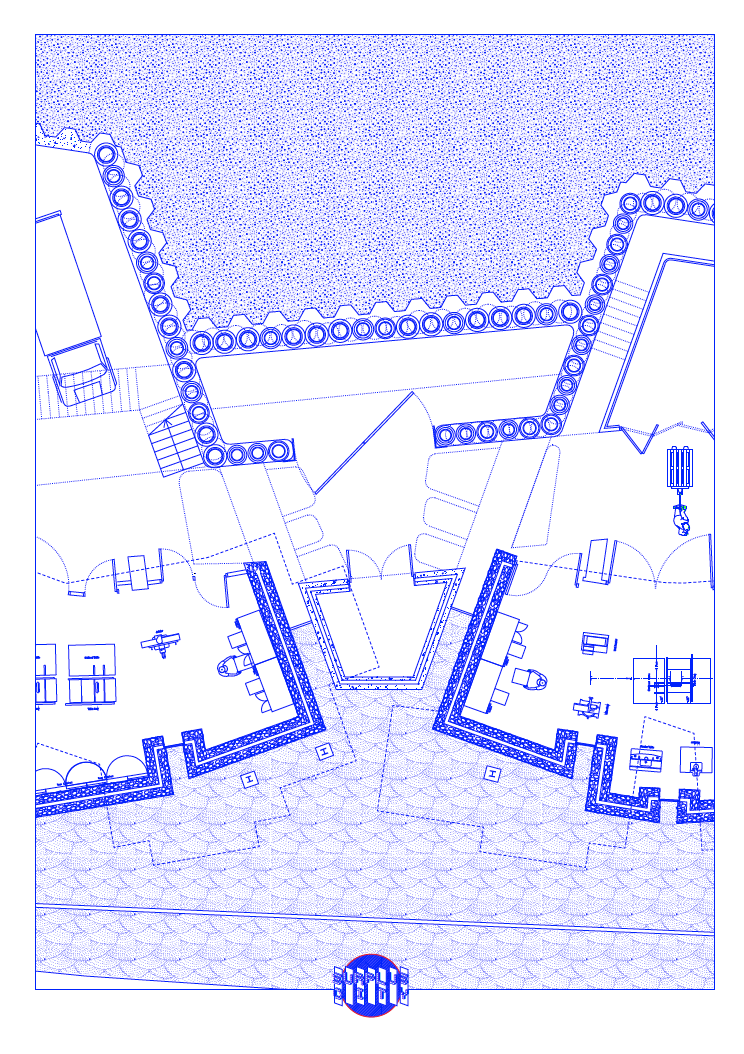

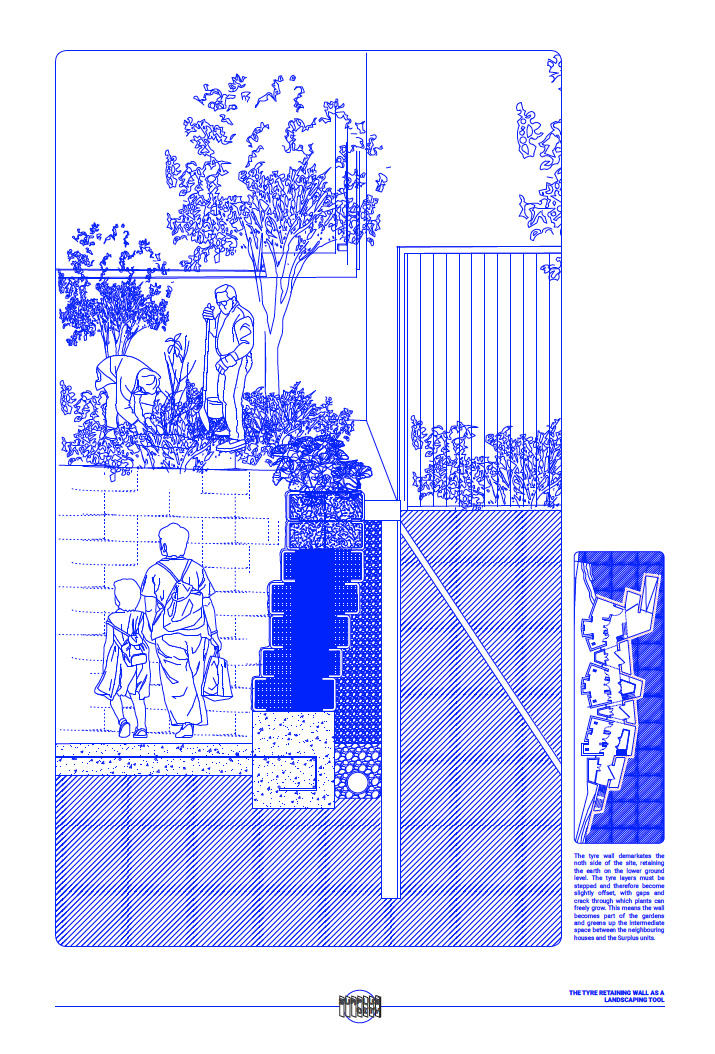

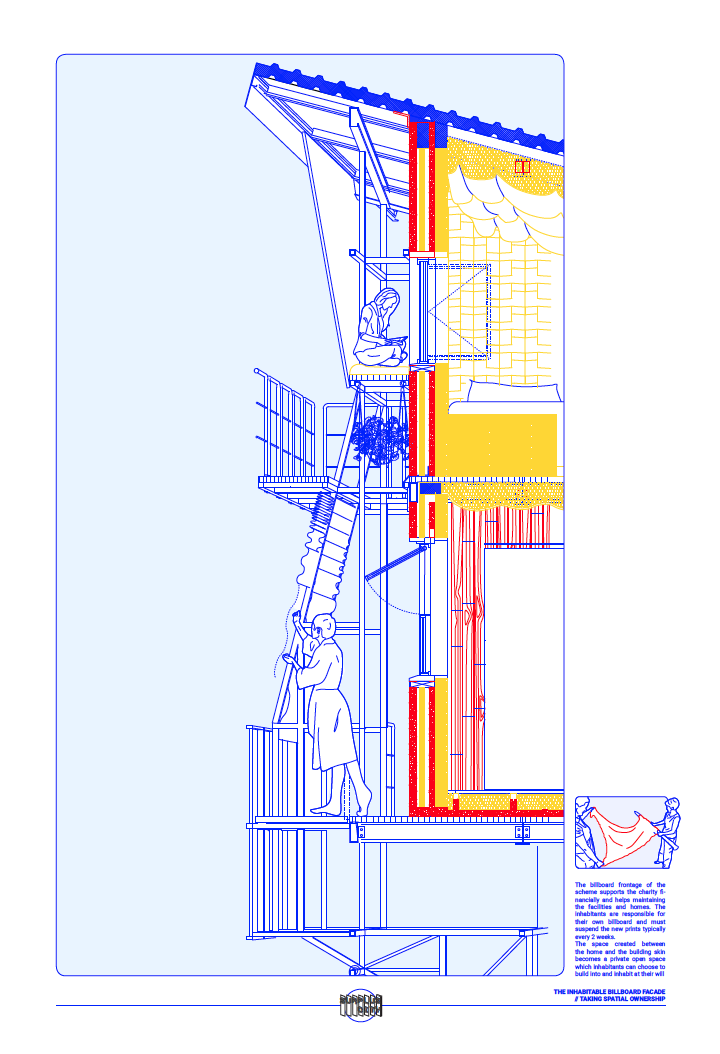

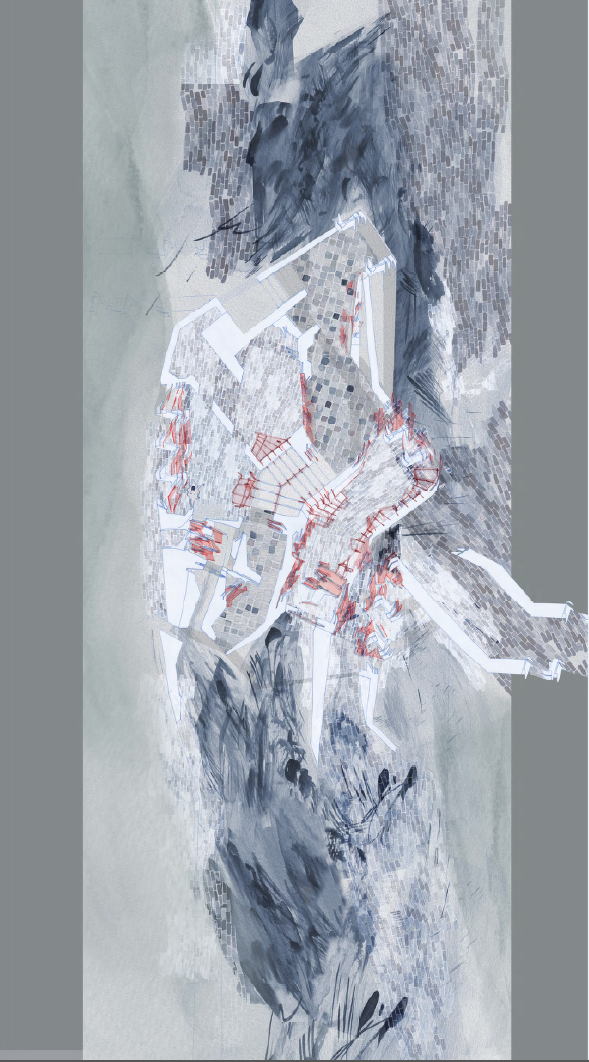

Park Royal Surplus City, London

Cheonggyecheon River – Four Moments celebrating Water